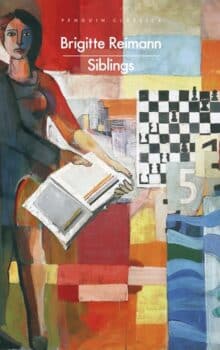

Brigitte Reimann’s Siblings has just been published in English translation by Penguin in its series of classic international literature. It comes 60 years after the original German novella appeared. The translator is Lucy Jones.

Why is a text like this of interest to the modern Western reading public? Its primary interest lies in the fact that here we have an authentic female voice communicating to us from the early 1960s what it felt like to live in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) just before the border between the two German states, the Berlin Wall, was finally sealed in 1961. What kind of society was developing in the 12 years since the foundation of the two German states in 1949? What kind of people?

The Cold War had begun even before the defeat of fascism in Germany in 1945. It had escalated to such an extent that the Western allies introduced a new currency, the Deutsche Mark, in the Western zones in 1948, establishing an exclusive economic area, followed in consequence by the establishment of the West German state (the Federal Republic of Germany) in May 1949. A few months later, in October 1949, the Soviet authorities had no choice but to follow suit, with the founding of the East German state, the GDR. Soviet plans right up to 1952, when Stalin was still the Soviet leader, to form a united, demilitarized Germany in Central Europe as a neutral, stabilizing buffer between the Cold War Powers were rejected by the West, obviating such a solution.

Siblings

By Brigitte Reimann

Translated by Lucy Jones

Penguin Classics, 2023

ISBN: 9780241555835

144 pp.

From 1949 to 1961, hopes to reunite Germany remained in the East. The GDR national anthem illustrates this, as it contained the lyrics “Deutschland, einig Vaterland” (Germany, our united fatherland). The West German anthem continued to be that used under the Nazis, “Deutschland über alles in der Welt” (“Germany Above All in the World”—the anthem which continues in use to this day). However, as the Cold War accelerated, the Marshall Plan boosted the West German economy, while East Germany alone paid reparations to the USSR, a devastating “brain drain” from the East took place, sabotage of East German production sites, tens of thousands of people working in the West while shopping and living in the state-subsidized East.

Military espionage contributed to making the open border increasingly unsustainable. This led to the gradual closing of the inner-German border to stem the defection of the GDR trained workforce. For a few short years, people could leave illegally via West Berlin—until August 13, 1961, when all borders were sealed, and any easy transit of German nationals between the two German states was stopped.

Famous Western Cold War espionage novels are set at this time. Western history books spin their own version of events as historical fact. To access historical truth other than speaking to witnesses of the time, the art of an epoch can give a sense of what it felt like to be alive at a particular time. Siblings does this for the Fifties and early Sixties in the GDR.

Brigitte Reimann was a well-known GDR writer who died of cancer at the young age of 39 in 1973. Born in 1933, she knew the times she wrote about intimately. Siblings (Die Geschwister in the original German) had been preceded by other texts, which had alerted the GDR reading public to her—Frau am Pranger (1956, “Woman in the Pillory”) and Das Geständnis (1960, “The Confession”). These trace recent German history from the Nazi dictatorship, the full acceptance of the guilt of the past, to members of an East German family deciding in which of the two German states they would live (1963, Siblings).

In each one of these novellas, a young woman needs to make hard decisions. All of them are working women, protagonists that became Reimann’s signal subject. It appears again in Ankunft im Alltag (1961, “Arrival in Everyday Normality”) and finally in her unfinished novel Franziska Linkerhand (1974, which became known to English-speaking film buffs through the subtitled GDR drama based on the 1981 book, “Our Short Life”).

A new normality

An entire GDR literary movement was named after Ankunft im Alltag, the arrival of the society and its people into a new normality, the building of socialism and the world of work.

In 1959 a significant cultural political conference took place in Bitterfeld. The ruling party’s (SED) recent congress had directed that the working class should be enabled to conquer the heights of art, that any divisions between social strata be overcome and there be no gulf between art and life. Based on this, an event organized by the Writers’ Union in the petrochemical plant of Bitterfeld had determined the policy that GDR artists should spend time in production, run creative workshops in factories for aspiring working-class writers, from which some well-known authors later emanated.

Also, the artists themselves were encouraged to write about the lives of ordinary working-class people. Brigitte Reimann supported this movement heart and hand. She set her texts in working people’s contexts and also ran a writers workshop in a lignite plant in Hoyerswerder. It ought to be mentioned here that the GDR had very few natural resources: Large-scale lignite production was conducted often necessitating the removal of village communities from the lignite areas, a serious social problem that is not Reimann’s theme, but one that continues to this day across Germany.

Aspects of Reimann’s own biography are frequently reflected in her work. In Siblings, Elisabeth is a painter who is deeply involved with life in a lignite plant, as are other characters around her. The novella revolves around this industrial core; it is what forges the lives of the characters. There, she runs a workshop for worker painters, some of whom show real talent. And it is in this setting that a variety of conflicts arise.

Plaque on a house at 20 Liselotte-Hermann Street in Hoyerswerda recognizing the home of writers Brigitte Reimann and her husband Siegfried Pitchman / SeptemberWoman, April 12, 2012 (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license).

In addition and important, Reimann’s favorite brother Lutz defected with his wife and child to the West in 1960. She notes in her diary: “Lutz went to the West with Gretchen and Krümel (he is now—perhaps only two or three kilometers away and yet unreachable—in the refugee camp at Marienfelde). For the first time I have a painful sense—not simply a rational one—of the tragedy of our two Germanies. Torn families, opposition of brother and sister—what a literary subject! Why is nobody taking this up, why is no-one writing a definitive book?” And so Reimann herself writes Siblings.

Reimann’s contemporary Christa Wolf addressed the same subject of a young working woman having to decide between her fulfilling working life in the GDR or following her lover to the West in her novella Der geteilte Himmel (1963, first translation into English by Joan Becker [1965] Divided Heaven, more recently by Luise von Flotow [2013] They Divided the Sky; a film based on it was released in 1964, available with English subtitles).

Both novellas evoke for readers a sense of the complexities of social reality in the early Sixties in the GDR, shortly before the Berlin Wall was erected. The authors write in very different voices, both identify with the GDR as do their protagonists, and both continued to grapple with life in the GDR in their work to follow. Reimann in particular made the world of work the core sphere of her texts into which her characters and their conflicts are fully integrated. The most famous of these is arguably Franziska Linkerhand, where Reimann explores the difficulties presented by unimaginative bureaucrats to the young architect who strives to create homey accommodation and towns where people will live happily and in cultural fulfillment. Much later this same theme appears in Peter Kahane’s film The Architects (1990), the last film to be made in the GDR.

Epic stories arising from women at work, their growing social equality stemming from economic independence and early, far-reaching pro-women legislation, including abortion rights, became a hallmark of GDR literature and give a more profound insight into what this society had to offer than any Western commentary will ever do. This is not to say that GDR art was uncritical of society. Indeed, frequently, this was the sphere where the most open criticism was voiced and therefore the arts became critically important for GDR citizens.

Siblings too contains criticism of party apparatchiks with tunnel vision. However, the family which loses one son to the West, and another one almost, has a father who confronts his sons with the money their education cost society and what their defection means financially to the state. Daughter Elisabeth fully identifies with the aspirations of the socialist state and fights for her rights and her dignity within this new society when the situation arises. Reimann draws rounded, authentic characters who give complex expression to a spectrum of at times conflicting and contradictory political views both in the workplace and in the family. A sense of recent history is added through flashbacks to characters’ pasts.

The novella is of interest to the modern reader for a variety of reasons. For one, its sense of a dramatic change in the times, experienced again in 1989/90, captures some of the current political mood, where we are forced to face realities in a new way, take a stand, act.

Secondly, this novella, like most of GDR literature, expresses women’s confidence in their social equality to an extent that is unparalleled in Western literature and society at that time. Closely linked to this is Reimann’s search for and tracing of a new humanity emerging with the development of socialism. She asks in her work, and attempts to answer, how people change when living in a society that puts their interests before profits. She examines the extent to which they identify with this state. She looks at how this affects their daily lives, their relationships with one another. And in the case of Reimann’s characters, there is the added consideration how they overcome the conditioning of the Nazi past. Central to Reimann’s attempts to imaginatively address these questions is the role work plays in the development of a new type of person. Readers are not presented with a uniformly gray image of the socialist German state; we see color, initiative, energy.

Finally, and perhaps most relevant, is the parallel to the situation in so many countries today, that suffer a brain and skills drain of young people trained by them to the wealthier countries who pay nothing for fully qualified workers. This is true not only within the EU, but worldwide.

Reimann does not shut her eyes to the difficulties posed by bureaucrats, nor does she paint a black-and-white picture. But on the whole she is hopeful that socialism has a future in Germany. GDR literature and art have been widely suppressed as part of the blanket rewriting of its history by the West. Nothing of the country’s culture in the broadest sense—as intimately reflected in its arts—was deemed tolerable, and needed to be all but eliminated. Even today, there are few who defy this imposition and turn to GDR art to remember what had once been possible in Germany.

Dr. Jenny Farrell is a lecturer at Galway Mayo Institute of Technology in Galway, Ireland. Her main fields of interest are Irish and English poetry and the work of William Shakespeare. She is the associate editor of Culture Matters and also writes for Socialist Voice, the newspaper of the Communist Party of Ireland.