Enrique S Rivera

The Untold Story of Capitalism: Primitive Accumulation and the Anti-Slavery Revolution

International Publishers, New York, 2021. 208 pp., $21.99 pb

ISBN 9780717808663

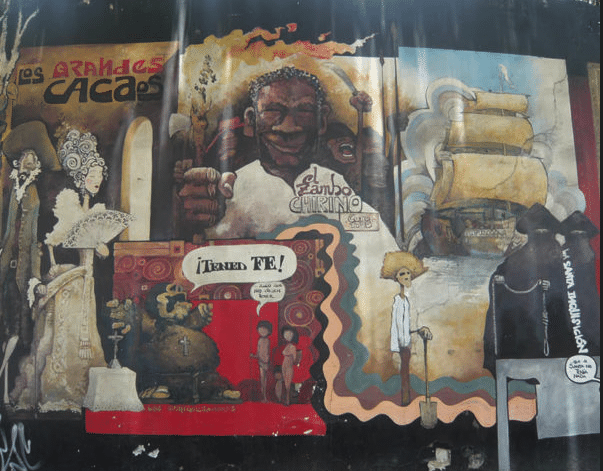

Every May 10th marks Afro-Venezuelan Day and commemorates the 1795 Coro Rebellion. The May 1795 revolutionary events are the centerpiece of Enrique S. Rivera’s The Untold History of Capitalism: Primitive Accumulation and the Anti-Slavery Revolution. Rivera’s careful use of the colonial archive to reconstruct the events in Coro, Venezuela is enhanced by his global mapping of the commodity and labor streams and colonial systems that conditioned the region’s political economy. He narrates the causes and events of a peasant-slave revolt that targeted for destruction colonialism, key features of the foundational stage of racial capitalism and racial slavery.

By 1795, Coro had become Venezuela’s second largest city with 150 plantations in its vicinity. Several smaller nearby indigenous towns populated by Ajagua and Ayamane peoples were forced to pay onerous taxes and supply labor-power to Coro’s ruling planter class. Plantation economies centered on livestock-based international trade, cacao production and sugar. Plantation owners and other European-descended city dwellers tended to be the main customers for Europe-originated consumer goods, such as expensive and fashionable textiles, tools and weapons, and other luxury goods. Enslaved Africans and racially mixed peasant farmers who depended on occasional wage labor to survive comprised the laboring population of the city and its environs.

Clothes and textiles appropriated by the insurrectionists were the key pieces of evidence in the subsequent investigation of the failed insurrection. Those ‘precious objects’ had been expropriated by the insurrectionists during their raids on plantation homes and redistributed to participants and family members. Rivera shows how luxury clothing items had marked racial and class status through prohibitive cost and punitive law. The ostentatious display of wealth was intimately tied to the presentation of white supremacy and class status (32). Thus, the insurrectionists’ appropriation and redistribution of clothes and textiles reveals how they targeted the plantation-slavery political economy and reimagined a political economy more closely aligned with their communitarian values.

Textiles imported by the plantation class were almost exclusively made in European centers such as Devon, Brittany, Flanders and the Guizpúcoa region of Spain. ‘European fabrics,’ Rivera shows, ‘were infused with a complex of social relations that shaped the nature of race, class, and revolution in the eighteenth-century Atlantic’ (33). Those social relations were rooted in the European slave trade that brought hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans to Northern Venezuela. Primarily responsible for this calamitous incarceration of Africans were the Dutch West India Company (WIC) and British South Seas Company (SSC) trading monopolies in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries alone. Coro’s white plantation owners eagerly exploited enslaved African labor and willingly engaged in that barbarous institution even as it increased the danger to their lives and livelihood as the May 1795 events revealed.

The WIC and SSC along with the Spanish Royal Guipúzcoa Company (RCG) were the three major trading monopolies in the region. The RCG was a Spanish public-private partnership specializing in the slave trade and shipments of cacao. The Dutch enterprise, which had been modeled on its far more successful East India counterpart, controlled a dozen slave-trading fortresses on Africa’s west coast. The WIC ‘served as a government administrative entity,’ managing security, transport and financial machinations for state and capitalist interests in the colonial enterprise (72). Born out of antagonism toward Spanish rule, the Dutch enterprise continued to operate illicitly in the Spanish Caribbean through its colonial station at Curaçao off Venezuela’s northern coast, smuggling enslaved people and as an entrepot for Venezuelan or indigenous traders seeking to avoid Spanish taxes on goods headed to Europe. Rivera attributes to the WIC the role of delivering most of the enslaved Africans to Coro, even though by the 1790s it had begun to falter. Many of the enraged participants in the 1795 uprising were either directly the victims of Dutch international trade or the descendants of those who had been kidnapped out of their home territories, now parts of Ghana and Congo.

In competition with the WIC, the British SSC gained legal access to lucrative Spanish markets. The SSC secured a Spanish 25-year asiento in 1713 and contracted to bring 75,000 enslaved Africa via Royal African Company-controlled Gold Coast slave forts to Spain’s American colonies. Along with this nefarious activity, the financial machinations of the company’s managers, through debt swaps and fictitious capital experiments, collapsed the London stock market in 1720. In addition to ‘structuring the plantation economies of places like Coro,’ the financial and political schemes that resolved the London crisis freed up massive amounts of capital to finance the private-public partnership that became the British Empire (100). As Marx proves ‘[t]he public debt became one of the most powerful levers of primitive accumulation.’ (Marx 1967: 607). In other words, the international trading system, a foundational element of emergent world capitalism, shaped the political economy of Coro and the conditions that led to the peasant-slave rebellion of 1795, even as it molded the still-emergent capitalist structures in the European metropole.

Rivera’s work bears the influence of historian Eric Williams, who had shown that plantation-based economic systems were designed as racially-based labor systems for extracting raw resources for production in European industrial centers. They were never intended as catalysts for full capitalist development in the Americas, Asia or Africa, even as the formation of planter classes generated competing, divergent interests from the metropole (Williams 2021: 42). Rivera frames his project with a comparable endeavor of mapping the development of capitalism as a world system and the localized American social relations of production. But he takes it one step further by exploring the circuits of production and accumulation on all three ends of the ‘triangular trade.’ He examines and elucidates the regional demographics of racial, class and gender hierarchies around Coro, and the productive relations managed by force, coercive taxation schemes and legal prohibitions. The plantation system continued in a transitional stage of feudal and capitalist relations of production as taxation schemes that forced peasant and indigenous people into labor service for church and private landlords could not fully monetize the economy. Spanish officials were forced to accept cocuiza plants (used for making rope) as exchange values for taxes and fees (165).

Rivera also attends to European production relations. At the time of the 1795 uprising, the sectors that drove the consumer markets in Coro lingered in a pre-industrial stage. Textiles sold to Coro’s planters primarily originated in Devon, England, the Brittany region of France and Flanders (one of the united provinces of the Dutch Republic). Rivera shows that while merchant capital had increasingly owned industrialized finishing operations for textiles, petty producers controlled most of the processing of raw wool or flax into cloth. These producers owned their looms and spinning machines but continued to render labor service or tribute to local landlords. In other words, Rivera contends, the industrial system remained primarily a semi-feudal operation not fully appropriated by capitalists. Over the eighteenth century, productive growth was tied to population growth. Petty producers earned a substantial real wage because, in this transitional mode, they controlled labor, tools and knowledge about the production process (54-55).

Rivera also explores the cultures and social relations of the societies from which enslaved Africans were kidnapped. Many of the enslaved Africans in Coro, forced into slavery via Dutch or British slave-trading enterprises, came from the Gold Coast (Ghana) and Loango (Congo). In contrast to private property relations dominant in Western societies, the several polities that existed in Ghana and Congo were kinship-based social formations organized as communal societies in which shared well-being was the driving political-economic principle. Rivera shows that such communal social practices remained prevalent in the lifeways of Coro’s enslaved and free African populations. Notably, large numbers of Africans, many of whom fled Dutch enslavement in Curaçao, lived in nearby maroon societies known as cumbés (126-135). These settlements developed social relations that extended their African cultural habits into the Americas and represented a dramatically different trajectory of human development than that which was led by their European neighbors.

The Untold Story of Capitalism’s subtitle draws attention to a longstanding theoretical concern within Marxism. Rivera argues ‘that it was primitive accumulation that gave rise to Coro’s plantation economy and the revolutionary movement that aimed to destroy it’ (p21). In other words, capitalist accumulation had yet to predominate in either European centers and or the plantation colonies, with primitive, non-capitalist and pre-capitalist forms of accumulation (and non-accumulation) remaining very much at play as types of potential generalized development. The peasant-slave revolt, which emanated from the cumbés, offered a development model that would be suppressed through mass killing, re-enslavement campaigns and final capitalistic development. Rivera’s research shifts the geographical locus implicit in many ‘origins of capitalism’ debates from localities in Western Europe to the motion, spaces, circuits and conflicts in multiple global sites and stages of economic production relations. Such a research paradigm most closely aligns Rivera’s research with Marx’s thinking.

Joel Wendland-Liu is the author of Mythologies: A Political Economy of U.S. Literature in the Long Nineteenth-Century and The Collectivity of Life: Spaces of Social Mobility and the Individualism Myth. His ongoing research includes a study of the Marxist concept of primary accumulation, the historical development of Marxist-Leninist thought in the U.S., and a study of radical U.S. literature in the twentieth century.

References

- 1967 Capital, Vol. I New York, International Publishers.

- 2021 Capitalism and Slavery Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press.