The Wall Street Journal (3/14/23) reports with evident alarm that “France has one of the lowest rates of retirees at risk of poverty in Europe.”

“The Party Is Ending for French Retirees.” That’s the headline the Wall Street Journal (3/14/23) went with just days before French President Emmanuel Macron invoked a special article of the constitution to bypass the National Assembly and enshrine an increase in the retirement age in national law. The Journal proclaimed:

The golden age of French pensions is coming to an end, one way or another, in an extreme example of the demographic stress afflicting the retirement systems of advanced economies throughout the world.

The possibility that this “golden age” could be extended is not even entertained. Due to previous “reforms” (CounterSpin, 9/17/10), the pension of the average French person is already facing cuts over the coming decades. So preserving the current level of benefits would require strengthening the system. For the Journal, this is out of the question. Stingier pensions, on the other hand, are portrayed as the inevitable result of “demographic stress,” not policy choices.

The French people, by contrast, recognize that a less generous pension system is far from an inevitability. Protesters quickly took to the streets this January after the government unveiled plans to raise the retirement age from 62 to 64; one poll from that month found 80% of the country opposed to such a change. And as the government pushed the reform through in March, protests grew especially rowdy, with monuments of refuse lining the city’s streets and fires illuminating the Parisian landscape.

But that’s just how the French are, you know? They’re a peculiar people, much different from us Americans.

The French are built different

A New York Times profile (2/24/23) depicted Jean-Baptiste Reddé as “a kind of ‘Where’s Waldo?’ who invariably appears alongside unionists blowing foghorns and battalions of armor-clad riot police.”

As the New York Times’ Paris bureau chief Roger Cohen put it in a recent episode of the Daily (3/16/23), protesters have been “talking about how life begins when work ends, which is a deeply held French conviction, very different from the American view that life is enriched and enhanced by work.”

Left unmentioned is the fact that, for decades, Americans have consistently opposed increases to the Social Security retirement age, usually by a large margin (CounterSpin, 10/26/18). Moreover, two-thirds of the American public support a four-day workweek, and half say Americans work too much. How French of them.

US media (Extra!, 3–4/96) have taken to covering the uprising against pension “reform” in the same way the narrator of a nature documentary might describe the wilderness:

Now, we come to a Frenchman in his natural habitat. His behavior may give the impression of idleness, but don’t let that fool you. If prodded enough with the prospect of labor, he will not hesitate before lighting the local pastry shop ablaze.

The New York Times (2/24/23), for instance, ran an article in the midst of the protests headlined “The French Like Protesting, but This Frenchman May Like It the Most,” about a man who has “become a personal embodiment of France’s enduring passion for demonstration.” It followed that up with a piece (3/7/23) presenting French opposition to an increase in the retirement age as some exotic reflection of the French’s French-ness. A source attested to the country’s uniqueness:

In France, we believe that there is a time for work and then a time for personal development.

Meanwhile, while the Washington Post has mostly been content to outsource coverage of the protests to Associated Press wires, it did run a piece (3/15/23) by one of its own reporters titled: “City of … Garbage? Paris, Amid Strikes, Is Drowning in Trash.”

The burden of old people

The Washington Post (3/17/23) urged the United States to join France in “forcing needed reforms to old-age benefit programs.”

This fairly unserious reporting on the protests contrasts sharply with the grave rhetoric deployed by the editorial boards of major newspapers in opposing the protesters’ demands. The Wall Street Journal (3/16/23), which has implored the French to face “the cold reality” of spending cuts, is not alone in its crusade against French workers. The boards of the Washington Post, Bloomberg and the Financial Times have all run similarly dour editorials promoting pension reform over the past few months.

Among these, only the Financial Times (3/19/23) opposed the French government’s remarkably anti-democratic decision to raise the retirement age without a vote in the National Assembly, opining that Macron’s tactics have both “weakened” him and left “France with a democratic deficit.”

The Washington Post (3/17/23), by contrast, suggested democratic means would have been preferable, but gave no indication of opposition to Macron’s move. (As FAIR has pointed out—3/9/23—the Post’s supposed concern for democracy doesn’t extend far beyond its slogan.) And the Wall Street Journal (3/16/23) actually saluted the move, remarking,

Give Mr. Macron credit for persistence—and political brass.

The editorial boards’ case for pension reform is based on a simple conviction—French pensions are unsustainable—for which there are three main pieces of evidence.

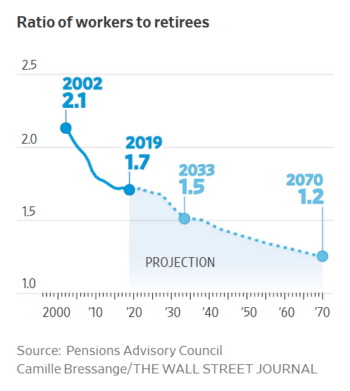

The Wall Street Journal graphic (3/14/23) does not note that over this same time period, from 2019 to 2070, the percentage of French GDP spent on pensions is projected to decline from 14.8% to 12.6%.

First, the ratio of workers to retirees. The Wall Street Journal (3/14/23) included a graphic projecting the worker-to-retiree ratio through 2070:

As the graphic shows, this ratio has declined substantially since 2002, and is set to decline even more over the next several decades. This trend is referenced more or less directly in editorials by the Journal (3/16/23, 1/31/23, 1/13/23), the Washington Post (3/17/23) and the Financial Times (3/19/23).

The declining worker-to-retiree ratio is meant to inspire fear, but in and of itself, it’s not necessarily a problem. After all, the increased costs associated with a rising number of retirees could very well be offset by other factors. It is therefore much more useful to look directly at how much of a nation’s wealth is used to support retirees.

Which brings us to the second commonly cited piece of evidence: pensions as a percentage of GDP. This is mentioned in editorials by the Journal (3/16/23, 1/31/23, 1/13/23), Post (3/17/23) and Bloomberg (1/16/23).

As it turns out, there’s no problem to be found here. In its 2021 Aging Report, the European Commission estimates that, even without a rise in the minimum retirement age to 64, public pension spending in France would actually decline over the next several decades, dropping to 12.6% of GDP in 2070, down from 14.8% in 2019. Cost-saving factors, primarily the deterioration in benefit levels, would more than cancel out the increase in the number of retirees. In other words, there is no affordability crisis. It doesn’t exist.

Which side are you on?

For the Financial Times (1/10/23), cutting pensions is “indispensable” because “plugging a hole in the pension system is a gauge of credibility for Brussels and for financial markets which are again penalizing ill-discipline.”

The only actual evidence for the unsustainability of France’s pension system is the system’s deficit, which is projected to reach around €14 billion by 2030. This piece of evidence is cited in editorials by the Journal (1/31/23, 1/13/23) and the Financial Times (3/19/23, 1/10/23).

One solution to the deficit is raising the retirement age. Another is raising taxes. Oddly enough, the editorials cited above almost universally fail to mention the second option.

The only editorial board to bring up the possibility of raising taxes is the Financial Times’ (1/10/23), which comments,

Macron has rightly ruled out raising taxes or rescinding tax breaks since France’s tax share of GDP is already 45%, the second-highest in the OECD after Denmark.

This statement says much more about the Times than it does about the reasonableness of raising taxes. Oxfam France (1/18/23) has estimated that a mere 2% tax on the wealth of French billionaires could eliminate the projected pension deficit. Rescinding three tax cuts that Macron’s government passed and that largely benefit the wealthy could free up €16 billion each year. That would plug the pension system’s projected deficit with money left over.

Which option you pick—increasing taxes on the wealthy or raising the retirement age—depends entirely on who you want to bear the costs of shoring up the pension system. Do you want the wealthy to sacrifice a little? Or do you want to ratchet up the suffering of lower-income folks a bit? Are you on the side of the rich, or the poor and working class? The editorial boards of these major newspapers have made their allegiance clear.

Conor Smyth is a recent graduate of Washington University in St. Louis, where he studied history and political science.