Culture implies our struggle; it is our struggle.

Sekou Toure

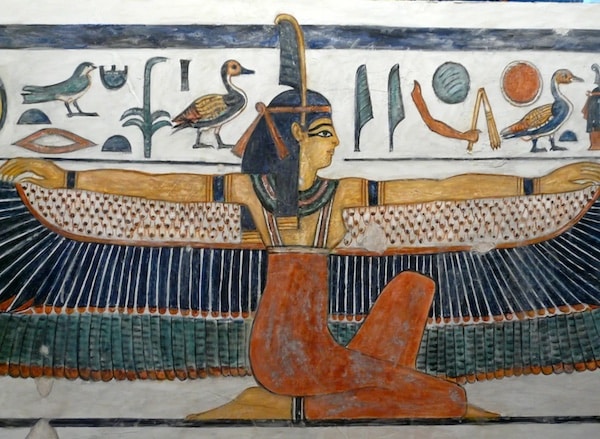

Garveyism and Afrocentrism, while different, are grounded in their shared nature of being expressions of a call for National conscience. Both call upon their adherents to recognize an “acknowledgment and need to return to origins” (Asa G. Hilliard III). The phrase suggests an understanding that black people across the globe represent a unified (at least in terms of shared struggle) though displaced people. Followers of these ideological trends argue that alongside shared struggle, there is a general “Afrikan worldview” and cultural logic that, due to slavery, has largely been forgotten. This gap in our memory has been caused by the forceful removal of Afrikans from their homeland and filled in by the decadent and fatalistic values & behaviors of the Europeans. The path to overcoming this “cultural amnesia” is via a total reorientation towards and (in some cases) overall destruction of the European’s contribution to human history and thought. In practice, this reorientation movement often takes the character of (1) outlining the values of “traditional” Afrikan people and counterposing them to the values of the Europeans. (2) From these values, the political-economic formation that Afrikan people need to combat and crush white supremacist domination is deduced. (3) When all is said and done, there is a call for us to spread these cultural maxims out to the diaspora (through different modes of education) and call for unity around those values.

What is the economic solution that is deduced from these so-called “traditional Afrikan values”? It can be either social democracy or some stripe of “collectivist capitalism” where our money is circulated between our people own to “build our strength” and “demand our recognition.” One thing is clear, there is a general refusal to accept the socialist option because it is reportedly a “white” thing. Ironically, when you ask these people from what country did capitalism originate, it is either met with quick dismissal or pointing out that “socialism in Afrika failed,” followed by being told to look at Thomas Sowell or that Brother from Kenya. The main point is that while the Afrocentrist/Neo-Garveyist is correct to critique the decadence of bourgeois society, their inability to move past culturalism leaves them in a position where they maintain the real system of Afrikan exploitation.

The Idealist Error of Afrocentrism

Before I address how a dialectical materialist must assess the importance of culture, we must first investigate the philosophical underpinnings of Afrocentrism a bit more. The position can be described as an idealism of a cultural type. What exactly do I mean by Idealism? Idealism is a viewpoint that the world is primarily determined or shaped by the content of minds (personal or some ultimate mind like God’s). Idealists believe that one only needs to change their thinking to change the world and that oppression is only a matter of perception. So what exactly makes it idealist? Quoting Norman Harris, Christopher J. Williams demonstrates the anti-materialism of Afrocentrism:

While not anti-materialistic, an Afrocentric orientation is one which asserts that consciousness determines being. Consciousness in this sense means the way an individual (or a people) thinks about relationships with self, others, with nature, and with some superior idea or Being . . . For example, the ancient Egyptian assertion, ‘Man Know Thy Self,’ indicates that the way one sees (thinks about and conceptualizes) the world precedes and determines life chances more so than exposure to or deprivation from various material conditions. (From “A Defence of Materialism: A Critique of Afrocentric Ontology, 2005).

For thinkers of this type, there is some unknowable essence preceding and permeating the existence of Afrikan people. As Na’im Akbar writes:

African Psychology maintains that the essence of the human being is spiritual. This means that human beings reduced to our lowest terms are invisible and of a universal substance. This writer (Akbar, 1976) has discussed elsewhere that the African conception of personality is fundamentally built on the notion of a force that defines the person’s continuity with all things within the world.

Akbar, Akbar Papers in Afrikan Psychology, p. 80

He remarks further:

African psychology sees the human being as ultimately reducible to a universal substance that affirms our oneness with the essence of the universe. Man’s worth is adjudged potentially as compatible as are the relationships between all of the mutually facilitating components of nature itself. The human being is considered as potentially harmonious and vast as the universe itself.

Akbar, Akbar Papers in Afrikan Psychology, p. 81

Pay close attention to the vagueness of this so-called spirit. If one has read their Hegel or even the works of certain Christian authors, you might be forgiven for believing that Akbar is affirming some all-encompassing Geist or God that grounds everything and guides our actions. In a preceding paragraph, there is a criticism of materialism as being prone to conflict (Akbar, 2004, p. 81). Apparently, to go above eurocentrism, We must think about this level and affirm a worldview of spiritual harmony and idealistic unity with the One.

Afrocentrists also argue that We must de-Europeanize our minds and develop an Afrikan Self-Conscious or Afrikanity (Kobi Kambon). What this means is not always clear, but the general thrust is, as stated before, a recognition that We are Afrikans and have a shared spirit or mode of being. There is very little mention of what conditions either the European or Afrikan state of mind. I’m guessing we’re supposed to assume a racialized Essence that is within the genes of the person vis-a-vis the amount of melanin that one has.

The issue with this position is found in its essentialism, unscientific philosophy, and primarily being a reaction to any and all things European. Without a material grounding, it allows for respect for LGBTQ people and anti-sexism to be attributed to Europeans and made not okay. To again quote Williams:

The Afrocentric failure to grant due recognition to the material bases of culture has an interesting political consequence: it buttresses the neoconservative claim that the problems facing African-Americans are fundamentally internal. This, in fact, is a key reason why it is so difficult to situate Afrocentrists on the radical liberal-conservative political spectrum. Notwithstanding their stated commitments to spearheading radical challenges to the prevailing order, Afrocentrists consistently divorce culture from structure and present African-American cultural orientations as primary obstacles to group advancement. This self-debilitation thesis is consonant with neoconservative rhetoric to the point where Afrocentric scholars regularly put forth arguments that would elicit nods of agreement from key figures on the Right.

I’m sure other New Afrikans have experienced this before: whenever there is an instance of police brutality, medical injustice, political oppression, etc., We are told that the issue is that our culture doesn’t allow us to be “respected” by our oppressors. When New Afrikan LGBTQ people are harassed, beaten, and even killed, We are told that it’s not our problem because our queer comrades are “sick” and that they had it coming. At other times, We are told that there is nothing fundamentally wrong with capitalism; it’s just that White people are the problem. In the last analysis, We have a mode of cultural nationalism that seeks to think away the problems of capitalist society and omnidirectional oppression rather than fight it head on.

Culture and Dialectical Materialism

How should dialectical materialists deal with the cultural question to avoid falling into the Afrocentric trap? The work of Amilcar Cabral and Sekou Toure provides a clue. First, what does the materialist mean by culture? We can use Toure’s definition from his speech “A Dialectical Approach to Culture.” He says:

By culture, we understand all the material and immaterial works of art and science, plus knowledge, manners, education, a mode of thought, behavior, and attitudes accumulated by the people both through and by virtue of their struggle for freedom from the hold and dominion of nature; we also include the result of their efforts to destroy the deviationist politics, social systems of domination and exploitation through the productive process of social life. Thus culture stands revealed as both an exclusive creation of the people and a source of creation, as an instrument of socio-economic liberation and as one of domination.

This definition highlights that culture depends on the relationship between people and their environment. It is not something merely spawned from the head. Indeed, one of the primary ways we come to understand a culture is through material artifacts such as pottery, tools, linguistic codes (like Sumerian scripts), and the like. We even separate historical periods through concepts like the “Iron or Bronze Age” or notions like “Feudalism, Mercantilism, and Capitalism.” It goes to show that the primary factor in cultural development is the political-economic arrangement and the effects of its productive relations.

In Cabral’s speech “National Liberation and Culture,” he states:

The value of culture as an element of resistance to foreign domination lies in the fact that culture is the vigorous manifestation, on the ideological or idealist plane, of the physical and historical reality of the society that is dominated or to be dominated. Culture is simultaneously the fruit of a people’s history and a determinant of history, by the positive or negative influence which it exerts on the evolution of relationships between man and his environment, among men or groups of men within a society, as well as among different societies.

Again, pay special attention to the fact that Cabral highlights that culture is an ideological expression of the material reality of society. Dialectical materialists do not ignore the role of culture. Instead, We point out that the call for cultural change is the ideological reflection of a need for the productive system to change. When one complains about the consumerism of Afrikan people or the high Black-on-Black violence, one should stop to consider the structural elements that bring about those practices.

How exactly should We understand the notion of “ideological reflection” in relation to base? Well, like the notion of simple and expanded reproduction in Marx’s Capital (where the production process cyclically reproduces itself), there is also the process of what is termed social reproduction. Indeed, in Capital, Marx tells us that not only are the productive forces reproduced in the average production process, but there is a reproduction of the necessary relations of capitalist production. In relation to culture as superstructure, everyday of our lives, but especially during childhood development, we encounter and internalize what that i term a “cultural logic.” This “logic” functions similarly to paths that all lead, in one way or another, to the same end.

During socialization, the child comes to acquire not only knowledge of an external world, a mother, and the like, but she also comes to acquire her culture. As the Soviet philosopher, Evald V. Ilyenkov states, “The child that has just been born is confronted – outside itself – not only by the external world, but also by a very complex system of culture, which requires of him ‘modes of behavior’ for which there is genetically (morphologically) “no code” in his body.” He says further,

Consciousness and will become necessary forms of mental activity only where the individual is compelled to control his own organic body in answer not to the organic (natural) demands of this body but to demands presented from outside, by the ‘rules’ accepted in the society in which he was born. It is only in these conditions that the individual is compelled to distinguish himself from his own organic body. These rules are not passed on to him by birth, through his ‘genes’, but are imposed upon him from outside, dictated by culture, and not by nature.

A similar concept is found in the Amerikan philosopher, George Herbert Mead’s, work Mind, Self, and Society with his notion of the generalized other. He says,

The organized community or social group which gives to the individual his unity of self may be called ‘the generalized other.’ The attitude of the generalized other is the attitude of the whole community. Thus, for example, in the case of such a social group as a ball team, the team is the generalized other in so far as it enters—as an organized process or social activity—into the experience of any one of the individual members of it.

So, We understand that the person comes into a cultural matrix already developed for him or her to which they are then enculturated. We have to remember however, that the culture of any society is largely going to be one that is most fit for the current mode of production and its social relations. For example, during the feudal era, the common sense of the time believed that the nature of reality reflected the experiences of priests, lords, and serfs. The intellectuals of the era erected a grand scheme called the great chain of being that places the serfs at the lowest tier right above animals and had the church at the top right underneath God. If one questioned this logic, they were more often than not, treated as a social outcast or severely punished. There is a similar trend in relation to the rise and maintenance of capitalism.

From the last sentence, a word must be said about the role of law in relation to the struggle. The Marxist legal theorist, Evgeny B. Pashukanis, makes an astounding point in his article “Lenin and the Problem of Law” when he points out that, “Under autocracy and under capitalism it [is] impossible to struggle with the legal impotence and juridic illiteracy of the masses, without conducting a revolutionary struggle against autocracy and against capital. [T]his impotence is but a partial phenomenon of the general subjugation for whose maintenance Tsarist and bourgeois legality existed. But after the conquest of power by the proletariat, this struggle has the highest priority as one of the tasks of cultural re-education, as a precondition for the construction of socialism.” Thus, We need to be wary of those who wish to ground our struggle in the purely ideological realm. In other words, We must engage in a war of position against the decadence of Capital viz. a seizure of the instruments of production and the repressive apparatuses of the state. Only with a structural victory can we hope to wage and win the so-called “culture war”.

What is to be Done?

The Afrocentrist’s call for “re-Afrikanization” is only completed when cultural ideas take on the material force i.e., when the latent will becomes the collective will focused in many hands. So, in the last analysis, the attitude we need to take towards Afrocentrism is “Yes, and?.” We need them to realize that We need more than a mere change of thought but a real revolution pertaining to the material base.

We must, in and by a struggle, recreate a new society based on the values which glorify the memory of its heroes. (Toure, “A Dialectical Approach to Culture” 1971.)