Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

In late 2022, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) released a fascinating report entitled Working Time and Work-Life Balance Around the World, in large part encouraged by a slew of initiatives across India to extend the workday. The report accumulated global data on the time spent at work in 2019, before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The ILO found that ‘approximately one third of the global workforce (35.4 percent) worked more than 48 hours per week’ and ‘one fifth of global employment (20.3 percent) consists of short (or part-time) hours of work of less than 35 hours per week’, such as gig work. Furthermore, the report noted that the occupational group with ‘the longest average hours of work was plant and machine operators and assemblers, who worked 48.2 hours per week on average’.

Birender Kumar Yadav (India), Government Work Is God’s Work, 2017.

Across India, there is an ongoing debate about a revision of the limits on the length of the working day. A bill in the state of Tamil Nadu sought to amend the Factories Act of 1948, which would allow factories to lengthen the workday from eight hours to twelve hours. In the Tamil Nadu State Assembly, government minister CV Ganesan said that the state—which has the highest number of factories in India—needed to attract more foreign investment, which would be easier if factories were permitted to have ‘flexible working hours’. Protests led by trade unions and the Left blocked the government, despite opposing pressure from the business lobby (the Vanigar Sangangalin Peramaippu). In February, a similar bill passed in the neighbouring state of Karnataka. ‘India is in competition with places all around the world to attract investments’, said Minister of Electronics, Information Technology, and Biotechnology Dr CN Ashwath Narayan; ‘Only when you have flexible labour laws, investments can be attracted’.

From Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research comes our own intervention into this debate, our May dossier, The Condition of the Indian Working Class. The dossier opens with two events from 2020. First, at the start of the pandemic, the Indian government callously told millions of workers to return to their villages, and second, India’s farmers began a powerful protest against the government’s attempt to transfer control of the mandis (‘produce markets’) to big corporations. These events demonstrate both the harsh behaviour of the Indian government and the corporate class towards workers as well as workers’ and peasants’ ongoing resistance to the structure that exploits and oppresses them.

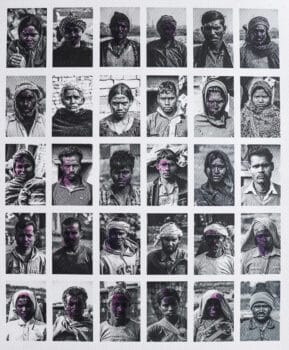

Birender Kumar Yadav (India), Erased Faces, 2015.

In 1991, India used a short-term balance-of-payments crisis to disrupt the institutional fabric of national development and open the economy to foreign investment. This ‘liberalisation’, as it is known in India, meant that capital was given a decisive advantage over labour and that labour protections hard won by the working class and the peasantry would be withdrawn.

Recognising this trend, Indian workers initiated a cycle of protests to defend their rights against what became known as ‘labour market liberalisation’. The key word ‘flexibility’ meant that workers would now have to surrender their precious rights to attract investment and deliver larger profits to those investors. Despite concessions made by workers—some forced, some through bargaining—the jobs produced by the neoliberal dispensation were work for the desperate. As we write in the dossier:

The promise of large-scale industrial investment and the creation of high-quality industrial jobs did not materialise in a significant way, and both economic and industrial growth have remained at low levels not only because of the lack of investment, but also because of the suppressed demand of the Indian population. This demand was reduced because of the desperately low wages of much of the population as well as neoliberal restraints on public spending, particularly in the agrarian sector.

What we find in India is not dissimilar to other parts of the world, with more and more workers slipping into increasing precarity. While the pandemic accelerated the rise of informal and unregulated employment, the ILO has shown through a number of regional studies—in Egypt for instance—that the trend towards precarious labour was already growing precipitously, with class war of a ruthless kind camouflaged in technical-sounding terms such as ‘labour market flexibility’.

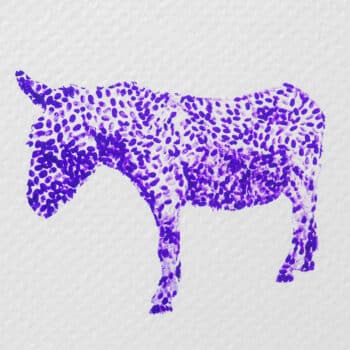

Birender Kumar Yadav (India), Donkey Worker, 2015.

In 2015, the United Nations passed a landmark resolution announcing seventeen Sustainable Development Goals, clearly stating the need to ‘Promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all’. The ILO understands ‘decent work’ to mean ‘full and productive employment, rights at work, social protection, and promotion of social dialogue’, or—in plainer language—the right to productive work, safe working conditions, social insurance, and collective bargaining.

It has been clear for a long time that ILO standards are simply not taken seriously by most countries. Trade unions and other organisations of the working class provide the only platform with liberatory potential, with the unity of sectoral unions and union confederations playing a key role for any such effort to succeed. To fight the proposed Industrial Relations Bill (1978), whose provisions would have weakened the right to strike, various unions formed the National Campaign Committee of Trade Unions. In 1982, this committee led a general strike against the imposition of the Essential Services Maintenance Act (1981), another attempt to enfeeble labour organising. Since 1991, this committee, alongside the joint platform of the Central Trade Union Organisations, has held twenty-two general strikes, each of them larger than the one that came before.

In March 2022, 200 million workers, from the industrial sector to the care sector, joined the general strike to shut down the country. These strikes have been massive because the trade union movement has taken up the battles of unorganised informal workers with the same energy as the battles of their own members, as K. Hemlata, the president of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions, pointed out in our dossier no. 18 in July 2019. The class struggle is alive and well, although one of the weaknesses of our time is that these massive mobilisations have not been easily converted into political power. Financial power has drowned democracy, and the rise of toxic right-wing ideas—including religious fundamentalism—has played an influential role in communities struggling with the gradual destruction of collective life (a phenomenon we discussed in dossier no. 59, Religious Fundamentalism and Imperialism in Latin America). Nonetheless, as we write in the closing sentence of our new dossier, the workers ‘remain alive to the class struggle’.

Birender Kumar Yadav (India), Walking on the Roof of Hell, 2016.

In early summer 2020, my heart sank watching millions of workers drag their tired feet across the overheated landscape of India. Gulzar Saab, one of the country’s great poets and film directors, watched this exodus of the working class and wrote a poem that captured the mood, Marenge To Wahin Jaa Kar Jahan Par Zindagi Hai (‘They Will Go to Die There, Where There Is Life’). We are grateful to Saab for letting us publish this poem here, translated by Rakhshanda Jalil:

The pandemic raged.

The workers and labourers fled to their homes.

All the machines ground to a halt in the cities.

Only their hands and feet moved.

Their lives they had planted back in the villages.The sowing and the harvesting was all back there:

Of the jowar, wheat, corn, bajra—all of it.

Those divisions with the cousins and brothers.

Those fights at the canals and waterways.

The strongmen, hired sometimes from their side and sometimes from this.

The lawsuits dating back to grandparents and grand uncles.Birender Kumar Yadav (India), May Day, 2022.

Engagements, marriages, fields.

Drought, flood, the fear: will the skies rain or not?

They will go to die there—where there is life.

Here, they have only brought their bodies and plugged them in!They pulled out the plugs:

‘Come, let’s go home’—and they set off.

They will go to die there—where there is life.

The art in this newsletter, taken from our latest dossier, is by Birender Kumar Yadav, a multi-disciplinary Indian artist from Dhanbad, a city of iron ore and coal built on the backs of mineworkers and indigenous people. Much of Yadav’s work, informed by his early experiences as the son of a blacksmith who worked in a coalmine, draws attention to unjust class hierarchies and the plight of the working class.

Warmly,

Vijay