Returning from 12 days in Cuba in mid-May, I spent an uncomfortably long six-hour layover at the Miami airport, waiting for my connecting flight to New York.

It wasn’t uncomfortable just because of the usual inconveniences like overpriced food and crappy seats but because I was a trans woman existing in the state of Florida, where the far-right anti-trans crusade has been centered this year.

As I sat in Miami, I was keenly aware that Gov. Ron DeSantis was preparing to sign several laws aimed at banning trans people from public life and getting the health care they need to live.

(DeSantis did sign these laws just a few days later, not by coincidence, on May 17—the International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia, and Transphobia.)

One of those state laws bans trans people from using public restrooms that match their gender expression—including those in airports. When that law takes effect on July 1, trans women like me will be faced with the choice of risking arrest using the women’s room or risking humiliation and violence using the other option.

During my six-hour sojourn, I used the airport restroom three times. Yes, I kept count; I was on guard for my safety and hyper-aware of everything around me. But as usual, no one objected to my presence or even noticed.

Waiting in Miami, I had plenty of time to reflect on the stark contrast between Cuba, where queer rights are advancing by leaps and bounds, and the United States, where they are being dragged backward by state-sanctioned violence.

That violence comes in the “official” form carried out by bigoted politicians like DeSantis and the off-the-books sort used by fascists coast-to-coast, who get a wink and a nod from the cops and big bucks and lavish media attention from the capitalists.

International Trans Colloquium

In May, I was part of the LGBTQ+ delegation to socialist Cuba organized by Women in Struggle-Mujeres en Lucha in cooperation with the Cuban Institute for Friendship with the Peoples (ICAP) and the National Center for Sex Education (CENESEX).

We went to learn about Cuba’s revolutionary new Families Code, adopted by referendum last year. This document, described as the most advanced of its kind in the world, elevates the legal status of queer and other nontraditional families. It expands the rights of LGBTQ+ family members, children and youth, elders, people with disabilities, and more.

We also went to learn about the effects of the six-decade-long U.S. blockade on LGBTQ+ Cubans and all Cuban people. Our mission was to bring back information to help educate our communities, encourage them to oppose the blockade, and understand that another world is possible.

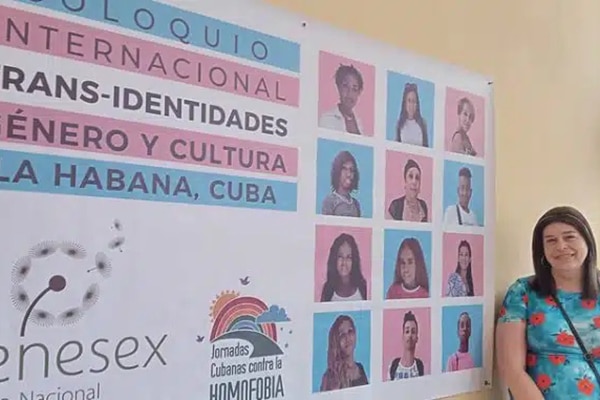

Officially, our delegation lasted for one week, from May 7-14. But two of us, both trans women, arrived in Havana a few days earlier to attend the VII International Colloquium on Trans Identities, Gender, and Culture, held from May 4-6.

This annual event, organized by CENESEX, brings together experts, medical professionals, and academics from several countries to discuss the latest research on gender-affirming care and the social challenges facing trans communities. This year there were participants from Mexico, Italy, Argentina, the U.S., and other countries, as well as Cuba.

Trans voices heard and respected

A lot of valuable information and views were shared throughout the colloquium. It was especially enlightening to hear how U.S. anti-trans propaganda is rippling throughout Latin America and Europe.

But for me, the most memorable moment came during the first afternoon’s session, held in the beautiful building that is home to CENESEX.

A panel of doctors and researchers had just spoken about the medical challenges of gender-affirming care, from hormone therapy to surgery to mental health and treatment for trans youth. A group of trans women from Cuba, Uruguay, and Mexico had been sitting in the front row, listening intently to the presenters.

After the final panelist spoke, the women consulted among themselves, then demanded the floor. They objected to the tone and perspectives of some of the experts, who focused entirely on clinical research and standards of care divorced from the actual lived experiences and needs of trans people.

Mariela Castro Espín, CENESEX director and convener of the colloquium took the floor to support the trans activists, emphasizing how Cuba’s approach to all kinds of health care, and trans health in particular, can never be divorced from the social conditions of the people it serves.

I couldn’t help but imagine what would happen if a group of trans activists demanded the floor at a medical or academic conference in the U.S. to object to statements by official presenters. In all likelihood, they would be dragged out by security, perhaps even arrested.

This has happened in several U.S. state capitols recently when people dared to speak out against anti-trans legislation in those supposed “houses of the people.”

But at this international event in Cuba, hosted by an official body of the Ministry of Health and in the presence of representatives of the country’s media, trans people were not only free to take the floor and voice their concerns; their opinions were treated with respect and, in my view, helped change the tone of the rest of the conference.

Conga and the future

Following the conclusion of the International Trans Colloquium, on the evening of May 6, we were invited to attend the Gala Against Homophobia and Transphobia at the National Theater near Revolution Square. The fantastic, colorful annual event featured well-known Cuban musicians, live theater and dance, and incredible drag performances.

Unlike the recent invitation-only Pride event at the White House in Washington, D.C., the gala was open to everyone, and the 3,500-capacity hall was packed with happy, cheering queer couples and families. Tickets cost the equivalent of 35 U.S. cents.

The following day, we welcomed the rest of the delegation, including activists from Atlanta, Baltimore, Los Angeles, and New Orleans.

Over the next week, we attended several sessions at CENESEX to learn about different aspects of the Families Code and the development of queer rights; we visited a polyclinic to learn more about Cuba’s primary health care system and how the recommendations made by CENESEX for trans health care are integrated into the system from top to bottom; toured the Denunciation Memorial, a museum that exposes the history of U.S. terrorism against the Cuban Revolution; and received a briefing at the biotechnology center about Cuba’s development of groundbreaking vaccines.

We also met with the Federation of Cuban Women and learned about its long history of elevating LGBTQ+ issues (going back to the early 1970s); spoke with district representatives about their responsibilities as elected community leaders; received a guided tour of the new Fidel Castro Center, documenting the life of the Cuban revolutionary leader; and finally, visited the national capitol to learn about Cuba’s electoral and legislative process from a member of the National Assembly of People’s Power.

One of the most exciting things I learned about was Cuba’s constitutional “progress principle.” This means that once granted, rights cannot be taken away. How unlike the U.S., where every one of our hard-fought rights is liable to be rolled back like the right to abortion was a year ago!

On our final full day in Havana, we joined the Conga Against Homophobia and Transphobia, marching through the streets shoulder to shoulder with our Cuban siblings, chanting, “¡Socialismo, sí! ¡Homophobia, transphobia no!”

The memory of the marchers’ joy and political determination, of the happy neighbors and families cheering from apartment windows and sidewalks, of revolutionary political leaders in the front ranks, helped me get through the long hours in Florida, a state increasingly suffocated by censorious, repressive, and frankly murderous laws meant to keep workers down and the rich on top.

In Cuba, I was never misgendered, never worried about using a restroom, and never felt unsafe for being openly and unabashedly myself. I want that for myself and all my trans siblings, everywhere, every day.

As I boarded my flight home, I felt more determined to build a National March to Protect Trans Youth and Speakout for Trans Lives in Florida this autumn—to give hope to our trans community there, to other communities under attack, to all of us. And more convinced of the need to show the LGBTQ+ movement that the Cuban path—the path of revolutionary socialism—is the way forward to trans and queer liberation.