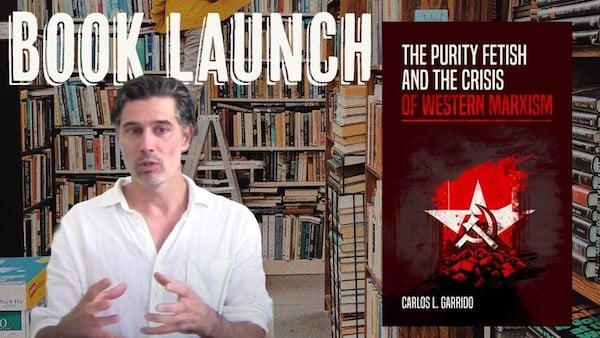

This is a transcript from Gabriel’s presentation at the book launch of Carlos Garrido’s The Purity Fetish and the Crisis of Western Marxism, which you may purchase HERE.

Noah Khrachvik: Our next speaker is Gabriel Rockhill. Gabriel Rockhill is a Franco-American philosopher, cultural critic and activist. He is the founding Director of the Critical Theory Workshop and Professor of Philosophy at Villanova University. His books include Counter-History of the Present: Untimely Interrogations into Globalization, Technology, Democracy (2017), Interventions in Contemporary Thought: History, Politics, Aesthetics (2016), Radical History & the Politics of Art (2014) and Logique de l’histoire (2010). In addition to his scholarly work, he has been actively engaged in extra-academic activities in the art and activist worlds, as well as a regular contributor to public intellectual debate. Follow on twitter: @GabrielRockhill

Gabriel Rockhill: Thank you so much, comrades, it’s great to be here with you for this important event. I have a few congratulatory remarks for Carlos, and then I have three comments based on the book, which have to do with elements that inspired my thinking and conversations I’ve been having with organizers in my circles. So first and foremost, I think the book is quite an significant achievement, at two levels at least. One is that it manifests the collective ethos of everything that you’ve been doing at Midwestern Marx, which is quite an incredible undertaking. It is very impressive that a group of people can build on their own such a significant, collectively resourced institute that provides political education, brings people into the struggle, breaks down complex ideas, makes them accessible to a large audience, etc. You occupy a very significant position, and I think an important element of Carlos’s work has to do with the ways in which he’s been working with other people in this collective endeavor, not simply to fight intellectually against the purity fetish, but to build institutional power in order to struggle back against it. Collective institution building should never be given short shrift because it’s one of the most important things we can do.

The second achievement is that the book itself is highly accessible and very well written. It is also urgent, insofar as it addresses one the central problems facing the contemporary left, particularly within the imperialist core . It provides a resounding critique of the purity fetish, of controlled counter-hegemony, and other related issues, while also advancing a positive project. So it’s dialectical through and through, and that’s one of its strengths. It’s also a kind of manifesto for the anti-imperialist left. I would therefore encourage everyone to read the book. As Radhika pointed out, it is also relatively thin so you can get through it. It is erudite without being bogged down in academic referentiality.

Regarding the points that I want to highlight for discussion, the first one is that Carlos provides us with a very astute account of what I would call the dialectics of socialism. The relationship between capitalism and socialism is not a simple relation between two fixed socio-economic systems, as if there would be capitalism over here, which would be “A” and socialism over here, which would be “B.” On the contrary, socialism is a collective project that is built out of the skeletal system of capitalism in its decline. Therefore, socialism inherits so many of the problems that plague the history of capitalism. And it is tasked with doing something that is nearly impossible, which is moving from a system that is based on profit over people to one in which people are put at the center of the socio-economic system.

One of my favorite jokes that I’ve heard about the socialist project is the following: socialism looks good on paper, but in reality… you just get invaded by the United States. This, of course, addresses the fact that we’ve never had a free socialist country emerge in the history of the world. We have only had what Michael Parenti calls “socialism under siege”: every single socialist experiment has been the target of imperialist destruction. This means that socialism as it emerges in the very real world has to deal with these concrete material factors that it does not control, because it is coming from the bottom up, within a world-system dominated by capitalism.

Moreover, socialist countries need to develop by starting out from a position within the geopolitical world of structural under-development. They have to do this without relying on many of the principal mechanisms of development under capitalism, such as colonialism and extreme forms of racist super-exploitation. Finally, socialists inherit all of the political and moral injustices of the capitalist system—baked in racism and homophobia, misogyny and gender oppression, all of the ideologies of the capitalist world—as well as ecological degradation.

I think that Carlos’s book does a good job of bringing to the fore this dialectics of socialism and the fact that we should never expect a pure and perfect socialist system to spring forth fully formed as if from the head of Zeus. Instead, we should actually anticipate that socialism will be wracked by a whole series of contradictions related to the fact that it is born out of a system of human and environmental degradation, which is the capitalist system. What is absolutely remarkable, and again Carlos’s book brings this to the fore, is that in spite of all of these odds, or against all of these odds, if you look at the quantifiable data that we currently have, socialism has registered some truly remarkable victories. In fact, there’s an interesting study that was done in 1986 that used data from the World Bank, which couldn’t be accused of being a communist sympathizer, and which is arguably the largest body of data globally. This study compared the Physical Quality of Life Index—which is a composite index calculated from life expectancy, infant mortality rate, and literacy rate—in socialist and capitalist countries at similar levels of development. It found that socialist countries had a more favorable performance in 22 of 24 comparisons.

So what’s extraordinary is that even though socialism emerges in this dialectical tension with capitalism, it has nonetheless proven itself successful at the level of its material gains for working people. In that regard, Carlos’s book is an invitation for us to think very differently about the socialist project than the Western fetishization of purity tends to make us think about it. That is, it encourages us to both recognize the extreme difficulties of the socialist project and also support and celebrate the incredible gains that have been made for humanity, and for that matter planet Earth, given the environmental policies of socialist countries. On the latter front, there have, of course, been times of significant contradictions between the need to develop the productive forces in underdeveloped countries and the ecological footprint that this brings (until the productive forces have been developed to the point of being able to work through the contradictions, as in contemporary China for instance).

My two other comments have to do with a series of thoughts that were provoked in both reading Carlos’s book and then discussing it with some people who are very close to me. The first is how the purity fetish relates to the longstanding criticisms of utopian socialism, and in particular those that were already expressed by Marx and Engels. You can look at the Communist Manifesto or the Poverty of Philosophy, where Marx explains that utopian socialism was largely a product of the lack of development of both the capitalist system and the state of class struggle at that point in time. This meant that the class struggle had not yet fully revealed to the working class the systemic workings of the capitalist ruling class, and therefore scientific socialism, as it emerged with the work of Marx and Engels, was actually a consequence of the material evolution of both capitalism and class struggle.

So one of my questions for Carlos is: How would you situate your understanding of the “purity fetish” in relationship to these longstanding critiques of utopian socialism, and in particular those critiques that foreground the material forces that are operative behind these ideologies. I think this echoes some of the things that Radhika said because I’d like to hear Carlos more on the central role played by the labor aristocracy in the history of the imperial left, and what kind of material forces are operative behind this. I’m thinking here of the promotion of the idea that socialism has to be something that is structurally impossible: it has to be absolutely pure and come forth in the world in a way that would be untainted by the history of capitalism. In short, it has to be basically immaterial. And ultimately that’s what a segment of the Western left wants: an immaterial socialism, meaning one that would never exist. This would thereby preserve the extant social relations such that this segment of the left would remain at the top of global labor structures.

My last comment has to do with leftist organizing in the imperial core. If we take seriously the material role of the labor aristocracy in promoting certain forms of ideology, such as that of the “purity fetish,” then what is to be done? I was recently reading the book Communisme by Bruno Guigue, which I strongly recommend. Drawing on Gramsci, he argues that the class struggle within the imperial core takes on a different form. Since socialist revolutions have generally proven themselves to be successful across the tri-continent, meaning the global south, and we have not had one within the global north of the imperial core, it makes sense that class struggle here would take on a slightly different form.

Guigue draws on the distinction that Gramsci makes between a war of position and a war of maneuver. Within the imperial core, there is such a deeply developed level of industrialized ignorance, due to the power of the cultural and media apparatus, as well as the system of indoctrination referred to as education. The Western left is therefore faced with a very fundamental problem, namely that the masses, for the most part, are profoundly uneducated about very basic things about how the world works (which, of course, is not necessarily their fault).

Guigue suggests, therefore, that what we need in the imperial core is a war of position, meaning a form of trench warfare in which we focus primarily on hegemonic struggle, fighting for political education. The war of movement, the war in which you’d actually be able to seize power in a revolutionary manner, as has been done across the global south in certain instances, is for the most part, I take it—that’s at least what he’s implicitly suggesting—not really on the table at this point in time. It doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t advocate for developing the necessary conditions. Someone like George Jackson is quite clear in this regard: if there is not a revolutionary situation, the onus is on us to make one.

Guigue’s position, I take it, is that to do that in the imperial core requires tasks that are slightly different. The fight against the purity fetish that Carlos is undertaking in this book is part of—it seems to me—a larger struggle for political education and for wresting control away from controlled counter-hegemony, while building up a realcounter-hegemony—like Midwestern Marx is trying to do, like the International Manifesto Group is endeavoring to do, as well as the Critical Theory Workshop and many other organizations with which we all work.

These are my three general thoughts on Carlos’s book, including a few questions for the discussion to follow. I’ll finally close just by saying that it’s extremely impressive and inspiring to have such a young scholar and vibrant mind doing such important work at an early stage in his career. I really look forward to continuing to collaborate with everyone at Midwestern Marx, learn more from you, and continue the struggle.