Introduction

I could not sleep because the murders of Banko Brown and Jordan Neely in big cities on the “progressive” coasts has me reflecting heavily on how their experiences as QTGNC individuals, lumpenized individuals, and criminalized individuals are extremely relevant in this current moment of right-wing political fervor.

I myself am a QTGNC person, someone who was once street houseless, who grew up in the shelters and projects, a former foster kid, someone disabled and thus job-insecure, and someone who would have nearly become a hashtag myself some years ago (if not for the intervention of a bystander). These experiences, alongside my organizing as first a Black nationalist and then Black anarchist, and my studies of Marxist feminism as well as decolonial and queer/trans theories, guided me in my co-creation of a now-defunct formation called SQuAD.

SQuAD’s run was brief but pretty phenomenal in that we were the first exclusively both Black and trans/nonbinary above ground defense, political education, and mutual aid organization rooted in autonomous and anti-authoritarian principles in NYC. A combination of the praxis and spiritual innovation of STAR with the anti-imperial, Panther/BLA-derived outlook of Kuwasi Balagoon, SQuAD and our comrades (“the Kats”) prioritized the underclasses and most marginalized in everything we did.

Our relationship to liberal advocacy around lumpen, disabled, trans issues in the city was akin to that taken up by the radical wings of the og Civil rights movement: supportive through a needed militant dimension, yet critical through an equally essential analysis of hierarchy and class. Being co-founded by locals to our city, people knew us and knew of us, for better or worse. Hate us or love us, SQuAD’s short-lived run opened up unique interventions into the struggle for the “people of the street.” I am certain that similar strategies and tactics exist elsewhere and I hope that more will emerge soon, to keep our streetkin from dying.

But alongside practice, there must be a “roots-grasping science.” An economy of representation has done folks like Jordan Neely and Banko Brown an incredible disservice. TERFs have seized upon their deaths to justify carceral deputization among non-police actors, triangulating their respective forms of manhood and their overall embodiments with a threat to public safety and to asset protection. This is a form of racial-class paternalism that has implications for how the overall “nexing” of settler property and the nuclear family are upheld.

A conceptual framework is necessary for “transecting” how that paternalistic “nexus” dehumanizes and racializes people through gendered configurations of the body. Black feminism has provided the tools for that “transect,” especially in considerations of the division of labor, family structure, of metaphysics, and ideology. Yet, failures to fully grapple with various spandrels of embodiment in their dialectical motion persist and have made Black feminism vulnerable to cissexist capture. As far as an alternative, SQuAD is no more, and so I am currently not as involved on the ground like I once was to help push this. Instead, my focus has been on theorizing a synthesis of transfeminism, Third Worldism, Black anarchism, and critical human ecology that I hope will inspire present and future revolutionaries to push a “transected” view of gendered embodiment.

Free The Body, Free the Land: On Corporeal and Territorial Capture

An analysis that resonates with the materialist transfeminism I am looking for was put out during Women’s History Month 2023. This was the Free the Body, Free the Land statement from the New Afrikan Womanist Caucus in the MXGM. They were announcing that the Six Principles of their organization had been updated to specifically address Patriarchy from a more “expansive” perspective. They describe this shift as the culmination of a twenty year long process, a culmination from when they had first struggled to establish a position on Patriarchy in the first place. The resulting “expanded” view of patriarchy would now widen the analysis from “sexism” in the way typically thought of, concerning the oppression of heterosexual, cisgender women, to include (in their words) “all… oppressed based on gender and sexuality.”

Drawing on thinkers like Patrice D Douglass and Saidiya Hartman, the New Afrikan Womanist Caucus challenges TERF ideology in their new “expanded” view of Patriarchy. The March 2023 “Free the Body, Free the Land” statement analyzes the overturning of Roe v Wade alongside the passage of “Don’t Say Gay” legislation. In this way, they argue for a conception of New Afrikan struggle that “[does] not centralize cisness, the body, and the gender scripts that we may attach to them.” They ultimately name and “charge” transphobia as “an antiblack and patriarchally violent endeavor,” echoing the famous Black feminist maxim that “an attack on one of us is an attack on all of us.”

The New Afrikan Womanist Caucus had been responding to Alice Walker. Alice Walker pioneered Womanism in the 20th century as a more spiritual and ecological approach to the issues concerning women of African descent (and women of color more generally). Womanism brought concerns with the sacred and the earth that were deemed absent in the feminist movement. Many variations on Womanism emerged: that of Clenora Hudson-Weems, or of Shamara Shantu-Riley, or of Monica Roberts (who was transgender), building off a grounding in spirituality and constructions of womanhood, motherhood, and sisterhood respectively rooted in indigenous traditions. They claimed to not replace but rather complement feminism, or deal with issues in a more holistic manner than feminism, something deemed more suited to African thought and sensibilities. But flash forward to the 21st century and Alice Walker openly aligns with a white feminist who peddles transphobic, antisemitic, and racist ideas (JK Rowling, the author of the Harry Potter books). Alice Walker is not alone: whether Laetitia Ky or Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie, or several Womanist preachers, or even Dave Chappelle, a number of Afrikan people have come out in support of so-called “TERF” ideology.

In the TERF worldview, gender is socially constructed, not biologically-reduced. This is different from the typical view of gender, in which maleness and manhood, or femaleness and womanhood, are always one and the same. TERFS genuinely acknowledge “variation” in gender and/or sex, which is part of why their ideology was considered “radical” during the mid-20th century. But, even as TERFs agree with a social constructionist outlook, the TERF insists that the experience of gender–in all its diversity and variation–will never not be an adaptation to an underlying “natural fact” known as sexual dimorphism (biology in “two forms”). It’s a circular logic: humans are “socialized,” according to TERFs into rigid categories of Man and Woman, so gender isn’t natural; and yet that “socialization” is because of the dualist composition of traits in human biology according to TERFs, so gender is natural. What they have is a conservative and uncritical view of gender, but rebranded to sound progressive and conscious. This is what makes their ideology insidious: because it has inaugurated an alliance between white liberal and white right-wing movements. TERF ideology has also begun to establish an anti-trans coalition in the Afrikan community across political divides as well.

There is immense potential in the New Afrikan Womanist Caucus of the MXGM’s clear, visible, and nuanced critique of transphobic womanisms/feminisms. The “New Afrikan” concept has long been about understanding the Afro-American experience as a struggle of displaced indigenous people, who were enslaved and made captives of a colonial power. It defines us and regards our culture as something that emerges in spite of, rather than because of, the United States. A slogan like “free the land” connects us to histories of struggle in the so-called Black Belt in the South of Turtle Island. Here, Afro-american slaves were not only brutalized on the land, but regularly resisted said brutalization, forming maroon enclaves in partnership with Turtle Island Native nations and carrying out revolts, establishing free towns and autonomous municipalities. This rebellious fervor always shook the hearts and minds of settlers in the frontiers, in the North, and in the South, and was responded to in different ways by industrial and plantation capitalists, the State and its citizens/denizens. And part of it always included wrestling with kinship structure, the nuclear family, a sexual division of labor, and ableist as well as cis/hetero/inter/allo-sexist regulations on the body.

Thinking of resistance to corporeal and territorial capture alongside each other is essential from a global perspective. Anti-LGBT laws are being reinvigorated all over the world, in both the Global North and Global South. In the latter case, we see a conservative and uncritical view of gender, but rebranded to sound progressive and conscious (often framed as an anti-imperialist strategy). For the Womanists in this coalition, it is ironic to see unity with TERFs given that bioessentialism is antithetical to what Oyeronke Oyewumi would describe as the “world-sense” of indigenous Afrikan cosmologies. “World-sense,” she suggests, is different from “worldview” because it does not privilege sight and those material/power relations where stratification is justified by how anatomy and physiology are construed visually (The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses).

For Oyeronke Oyewumi, any engagement with gender relations of Africa would have to prioritize the local “world-sense” that is traditionally not “visuocentric” for many of the various ethnic groups, to understand the different ways that social organization is reckoned and negotiated and embodied especially with regards to African spiritual systems. Part of this would mean no longer assuming that a binary-gender “nexing” of human embodiment is universal, and for Oyeronke Oyewumi this also includes dispensing with the idea that Gender is what “nexes” human embodiment in all societies in the first place. The rising predominance of TERF-derived unity, however, is marginalizing indigenous Afrikan “world-sense” or even re-organizing traditional cosmologies in a Western light. And this is a project of Statecraft:

There is a sense in which phrases such as ‘the social body’ or ‘the body politic’ are not just metaphors but can be read literally.–The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses

Towards a Science of Self-Determination

The issue at hand as I understand it is this: that if the problem of the 20th century was that of “the color line,” then the problem of the 21st century must be that of the “nexus,” upon which “the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea” is imbricated.

The term “nexus,” describes a means of connection between one or several things. It is a point at which different objects are “linked,” so to speak. The concept of “nexuses” whereby material and power relations “imbricate” is my particular theoretical coinage, to describe a set of social forms that I hypothesize to be “nexing” of human embodiment.

The Nexuses “thread” the complex interactions endogenous (internal) to a given socio-ecological system and between that system and exogenous phenomena (those introduced from outside). Some of these nexing-forms correlate to we understand to be Gender, but there are others: Age-nexuses, Caste-nexuses, Lineal-nexuses, and more.

Across human societies, both gendered and non-gendered Nexuses exhibit varying degrees of valency–that is, combining and displacing power–in the metabolic life-activity for each given context. For example, many have observed that Age, Lineality, Caste, and Status exhibit considerable valency in the “threading” of African traditional societies, sometimes alongside or to more of a considerable degree than or even in place of Gender nexings. The structural consequences of these emergent “nexuses,” and their valencies, is a stabilization of the nature-nurture dynamics involved in what Marxists speak of as the mode of production and patterns of social reproduction.

Alongside the structural consequences of “nexing,” there are also the embodied consequences. But these require a synthesis of both material analysis and metaphysical analyses in order to that their attendant dynamics may be “transected,” rather than viewed in adaptationist and reductionist perspective. They are, like the nexuses to which they correlate, spandrels, and in making sense of them as such, we might further identify the possibilities and constraints in the constructive evolution of various societies and social struggles.

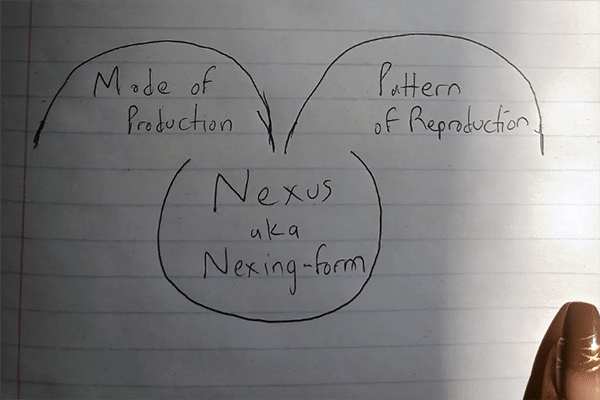

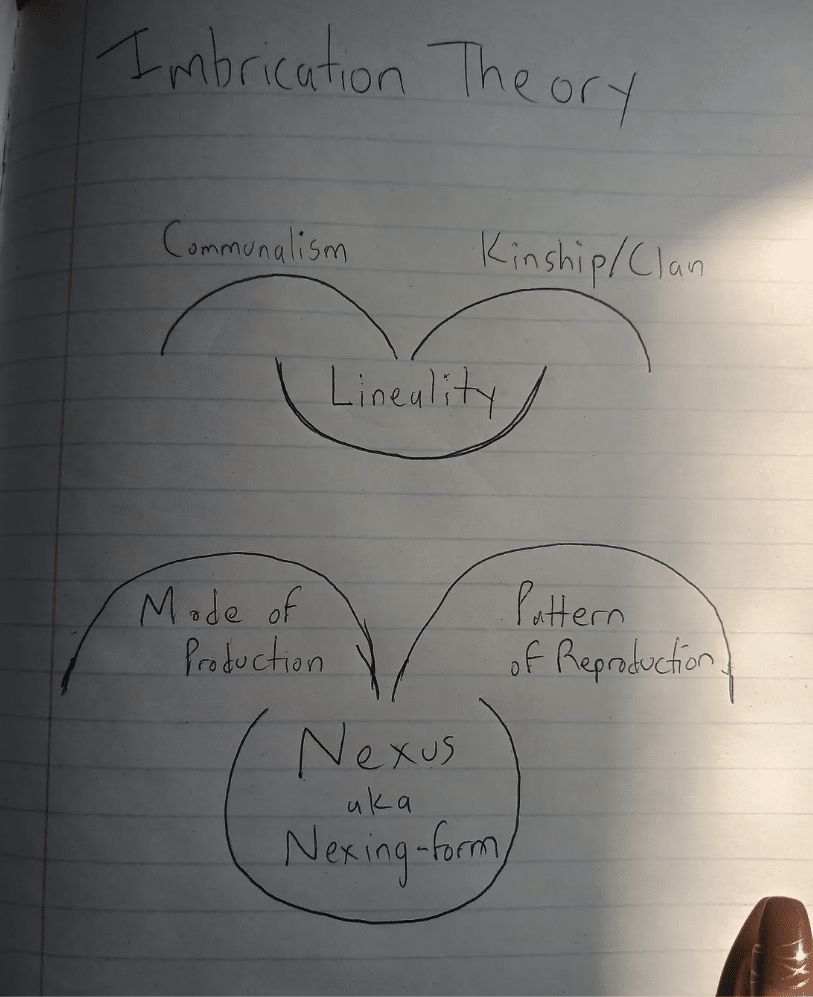

Nsambu Za Suekama draws two diagrams under the title of “Imbrication Theory.” In both diagrams, there are three shapes: first a U-shape, above which are attached a pair of inverted u-shapes. In diagram 1, the u-shape is labeled “lineality” and the pair of inverted u-shapes attached above it read “communalism” on one hand and then “kinship/clan” on the other hand. In diagram 2, the u-shape is labeled “nexus aka nexing-form” and the pair of inverted u-shapes above it read “mode of production” on one hand and “patterns of reproduction” on the other hand. NZ Suékama draws these diagrams as an attempt to “stretch” Marxist categories

We must, therefore, no longer regard either embodied spandrels or the Gender nexing-forms, or Age-nexuses, Lineal-nexuses, nexuses of Status, Caste, and more with which they are associated as “functions” of the economic life, or biology, or cosmology in a socio-ecological system of relations. This shift, however, does not suddenly render nexings of embodiment irrelevant to the analysis of the dialectical motion of such phenomena. Their relevance becomes a matter of constructive development ( and of sociogeny “alongside” phylogeny/ontogeny–word to Fanon).Modernity, I argue, has consisted in part of an ongoing structural articulation of the valences of the various “nexing-forms.” Kickstarted in the wake of colonial-imperial accumulation, the phenomenon of valency rearticulation is how global metabolic life-activity gets disorganized and reorganized vis-a-vis the capitalist mode of production and patriarchal patterns of social reproduction.

Herein arrives the entrenchment of a particularly rigid set of “gendered” and “non-gendered” relations, all configured vis-a-vis the core economic unit of bourgeois society: that locus of interaction for household and non-household production known as the “nuclear family.”

By this, a historical pattern of non-dualist and situationally dualist configurations of embodiment within human societies, all correlated to “premodern” nexing-forms that allowed for degrees of gendered mutability, especially outside the West and more “developed” regions of the First World, are gradually substituted by a near strict dualism that reduces embodiment to so-called “sex.”

Such a truncation ensures that the nature-nurture (metabolic) dynamics of human constructive development are “nexed” vis-a-vis labor inputs. The truncational process occurs in region-specific ways. Generally speaking, in the Above Ground sphere, this has come to consist of relegations defined in terms of Breadwinner and Homemaker (or measured against these positions); and, in the Underground sphere, more “illicit” kinds of labor relegations and other social roles predominate, although both spheres are not mutually exclusive. Here is where we may observe the “overlapping” character of dominant relations that the verb “imbrication” becomes important to describe.

Further, the roles being “nexed” herein are mistaken for facts of nature through a civilizing imperative that frames “sexual dimorphism” as essential to either the State’s guarantee of Divine grace or the State’s provisions of a liberal humanist “social contract” for its citizens and denizens. It is on this foundation that both individual “rights” and territorial plus cultural “sovereignty” of national groupings are imbricated within bourgeois relations.

Now, “post-modernity” consists of a haphazard “expansion” of liberal humanist “rights” and “sovereignty” after the fall of segregation, apartheid, and old colonialism/imperialism. We see the emergence of a putatively integrated, postcolonial, and increasingly multipolar nation-state metasystem, with the co-occurrence of both bourgeois and socialist modes.

Part of this has also meant the expansion of what Sanyika Shakur once spoke of as “Grand Patriarchy” and “Minor Patriarchy.” Newly independent states and their former dominating powers alike have stabilized their respective trajectories of “national development” through a “good ole boy network” (or nexus) and its attendant carceral-disabling-fascistic technologies.

The more diversified legal and extralegal forces involved in the coercions of embodiment that this “network” comprises have extended the combining and displacing power–the valency it holds vis-a-vis the evolutionary construction and deconstruction of human metabolic life-activity–exerted by the hegemonic nexing-form. This is a cross-class and cross-national problem, in which a “civilizing” imperative that mystifies labor relations behind naturalistic fallacies and a religious paradigm is now accompanied by an “emancipatory” imperative that takes the conditions of embodiment historically “nexed” in a “dimorphic” manner (and configured visavis the family, marriage, division of labor) at face value.

So, even where those conditions are denaturalized or desacralized, and rendered the objects of “critical” and “materialist” schools of analysis, they remain the foundation of various policies, programs, provisions, parties, etc. Thus, competing approaches to Statecraft ultimately still ensure that “sex” is the primary, sole, or ultimate factor to consider in matters of economic and social progress.

Concluding Remarks

The hegemonic “nexus” has revolutionary and reactionary forces united around an imperative of accumulation and of production misapprehended as functionally adapted to a “biological” reproduction imperative. The lens of “alongside phylogeny and ontogeny stand sociogeny” from Fanon, as well as the notion of “ecogeny” which I coined via Sylvia Wynter’s “sociogenic principle,” are important correctives. These allow us to raise consciousness of how and why the aforementioned “imperatives” become “lived” realities, all without taking the phenomena as a given (which is typical of modern evolutionary thought).

“Selective forces,” from this perspective, are interpenetrated with the dialectical motion of anthropogenic (human caused) activity, including the labor process. A linear-stagist theory of societal evolution, especially such as is found in The Origin of the Family, the State, and Private Property is exposed for its narrowness. The text correctly identifies, contra the transformational and variational models of evolutionary thought, that the evolution of Patriarchy as we know it is not externally overdetermined, nor rooted in something intrinsic to humanity. On these grounds, it is canonical in materialist and critical theories, whether through omission or commission, through agreement or disavowal. Yet, a “metabolic rift” that involves the emergence of modern gender relations amidst the enclosure of the commons is not considered within orthodox Marxism/feminism vis-a-vis a certain biological potentiality for the artificial selection of the traits of social embodiment. Instead, the “dialectic” inheres upon an a priori sexual dimorphism among the most vulgar (mechanical) Marxists and most exclusionary (radical) feminists.

Therefore, some embodied spandrels are the deictic center of the Marxist “science” regarding the “first fact” of “corporeal organization,” while others are relegated to the fringe of the analyses on social being. From Engels onward, the paradigm of “scientific socialism” would find itself stagnant in this manner, even where significant strides were made in other areas. And this is especially the case as its pioneers began to refuse “novel” insights in the natural and social sciences. This dogmatism, of course, became more apparent as struggles for bodily autonomy shifted the confines of the intellectual and social landscape of the West bloc and East bloc realpolitik.

New questions are to be asked now, and the conceptual frames being crafted to approach them must not be assigned solely to liberals nor to the conservatives. Autonomists must step up with queries like: how is it that the Gatekeepers among the Dagara people (word to Malidoma Patrice Somé–Gays: Guardians of the Gate) or the priests of Idemili among the Igbo people (word to Ifi Amadiume–Male Daughters, Female Husbands) become “gay” and “third gender”? First, we must consider the roles for their respective contexts as spandrels of embodiment in a nature-nurture and historical material process of constructive development.

A strict dualist sexual configuration of the body in these societies was only a situational (for the Igbo) or completely absent (for the Dagara) in the “nexing” of labor and other relations that concerned their conditions of living. For Igbo tradition, per Ifi Amadiume, situational gender rigidity is a consequence of an overall patriocephalous nexus, in which “headship” of various affairs–distinct from hierarchical authority–is stabilized through a focus on agnatic ties to kin or extended family, ancestors, the unborn, etc. Inheritance of spiritual roles, of land, and more, is never permanently rigid precisely because the patriocephalous nexus is non-dualist, and considerably fluid. Thus, anatomy did not anchor the place in Nnobi-Igbo culture that folks like Eze Agba (who is pictured in Ifi Amadiume’s research) occupied.

In Dagara tradition, per Malidoma Patrice Somé, gender rigidity is not detected even as an occasional spandrel of embodiment, an overall consequence of a nexus which prioritizes spiritual Energy. Role allocations are sourced by way of ritual customs, these initiatory rites exhibiting the valency in how the continuity of the tribe is stabilized. For this reason, phenotypic characteristics associated with sexual behavior/self-concept are not isolated as such, never relevant to the configuration of personhood. Thus, the conductors of ceremony (who Somé was learning from) are shocked when asked about their “homosexual attractions” because the atomized conception thereof is foreign.

Changes come as the demands of a bioessentialist reproductive “imperative” become a more significant & regular feature of the self-conception, praxis, and concerns of those occupying these indigenous roles, due to “encounter” with a certain gender nexus in the wake of colonialism + slavery. And such was the case for those called ’an daudu, jimbandaa, mugawe, ashtime, okule, mwaami, jo apele, and other spandrels of expansive gender embodiment (although in unique ways for each case). Indeed, we only know them now as such because of navigating the nexing-forms endogenous to each culture as well as the exogenously introduced ones. The latter, on account of modern valency articulation, is relevant to how changes in these spandrels of embodiment involve changes in “niche,” in the roles they occupied, even the appearance of new categories. With the arrival of slavery, Western states and empires, colonialism, cultural genocide through religious authority, the creation of borders and sovereignty frameworks on the Continent, comes the “progressive” threading of bourgeois divisions of labor by new gendered configurations of the body–the great many of which would attenuate racial dehumanization and ableist pathologization as much as it entrenched various cis/hetero/inter/allo-sexisms. A change in the conditions of their living co-occurs with a “progressive” shift in local spiritualities and indigenous “world-sense,” and ontologies, as well as the recombining and displacing of the characteristics of metabolic life-activity that concerned them, all threaded vis-a-vis changes in the “nexing” of embodiment within and across varying societies. We begin to observe, then— as a dominant mode of production, arrangement of power and authority, and patterns of social reproduction is globalized–the evolutionary “convergence” of gender outlawhood across the globe.

To mystify the process, the “gatekeepers” become simply “gay” in the pathologized understanding crafted by Western sexologists. Priests of Idemili become a “third gender” category in Western anthropology. The ’an daudu, the jimbandaa, the mugawe, the ashtime, the okule, the mwaami, the jo apele, and so many others become “abominations” within Western religious vocabulary. Their diasporic counterparts become “LGBTQIA+” within the Western humanist rights framework.

But with each shift, came forms of resistance that negotiated indigenous and imposed patterns, endogenous forces and exogenous forces. “Nexed” in this manner, there would emerge figures like Kimpa Vita, or Njinga of Angola, or the Amazons of Dahomey, or King Mwanga, or Ahebi Ugbabe, or Romaine-la-Prophettesse, or Xica Manicongo, or Mary Jones, or Cathay Williams, or Frances Thompson, or William Dorsey Swann, or Zazu Nova and Marsha P Johnson and the militants at Stonewall, the militants in the Compton Cafeteria Riots, the various “gender outlaws” of Africa and the Third World. As their “niche” became more rigid, they had to meet the new material and metaphysical demands, which in turn meant a shift in the forces that were operating on their bodies, their expenditures of energy and of focus, on their engagement in social labor, their self-concept and cosmological preoccupations, their beliefs and lifeways.

And, amidst this interplay, the “gender threads” of the color line have had to become more clear to us, and we have begun to understand ourselves through Struggles–for bodily autonomy and gender self-determination. As part of that, our Struggles must “transect” the dynamics of an embodied process of constructive development, in order to become conscious of themselves as historical material and nature-nurture consequences of said process. Autonomy, in this case, is about what implications the “overrepresentation of Man” has for both the metabolic (socio-ecological) and anthropogenic (human-caused) constraints and possibilities currently “nexed” vis-a-vis patriarchal imbrication. Autonomy in this case is a cognitive and behavioral and corporeal struggle, and it is also a spiritual struggle, a planetary struggle. The “children” will fly, the “dolls” will soar, the “bois” will arise, and all our “sibz” will mount up on eagle’s wings. In a whirlwind we shall come, like the bow in the cloud…

Mojo—An Afro-american term meaning magic powers or influence. In political sense, it means the magical hands of the people, their power to define political, social, economical, spiritual and military phenomena, and make or cause to move in a desired manner, i.e. to bring about revolutionary advancement to the evolution of [humankind].

— The BLA Political Dictionary

… all living organisms change the very conditions for living. Hence, the human propensity to do the same suggests social continuity with the natural world. Seen from a co-evolutionary view, the dynamic interactions between human societies, their built environments, and the biophysical processes of the earth require theory and method with which one can engage in analysis of material practice.

— Critical Human Ecology: Historical Materialism and Natural Laws

To escape the gender box is, in essence, to become an outlaw of sorts. For one’s escape from such restrictive confines is a protest—for one’s ability to be natural. Out and away from the stifling confines of patriarchy’s colonialism. But to protest is but one side of the equation. To protest is to go away from for self’s sake. An overstandable thing. But to rebel is to go against the malady in an attempt to destroy it.

— The Pathology of Patriarchy

To educate the masses politically does not mean, cannot mean, making a political speech. What it means is to try, relentlessly and passionately, to teach the masses that everything depends on them; that if we stagnate it is their responsibility, and that if we go forward it is due to them too, that there is no such thing as a demiurge, that there is no famous man who will take the responsibility for everything, but that the demiurge is the people themselves and the magic hands are finally only the hands of the people.

— Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth

If gender is socially constructed, then gender cannot behave in the same way across time and space. If gender is a social construction, then we must examine the various cultural/architectural sites where it was constructed, and we must acknowledge that variously located actors (aggregates, groups, interested parties) were part of the construction. We must further acknowledge that if gender is a social construction, then there was a specific time (in different cultural/architectural sites) when it was ‘constructed’ and therefore a time before which it was not. Thus, gender, being a social construction, is also a historical and cultural phenomenon. Consequently, it is logical to assume that in some societies, gender construction need not have existed at all.

— The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses

Articulation (structural)–derived from Quijano Anibal’s “Coloniality of Power” thesis. Focuses on how modernity relates to all historical forms of exploitation and domination. In NZ Suékama’s body of work, this process also involves a relationship between premodern and modern “nexuses” (see: Heterosexualism and the Colonial/Modern Gender System)

Biological potentiality–in contrast to biological reduction, biological potentiality emphasizes the range of traits, behaviors, etc that are made possible by factors like biological inheritance/descent, etc. But biological potentiality argues that these factors do not determine the presentation and evolution of that range of traits. According to Stephen Jay Gould, biological potentiality means there is no “predisposition” towards any of the available trait presentations. Social structure is biologically potentiated, not biologically reduced, and plays a major role in encouraging or discouraging the expression of traits and capacities in humanity (see: Who’s Man is This–Black Radical Ecology and the Anthropogenic Question)

Constructive development–hypothesis in biology that species can contribute to their own evolution over a long period of time by organisms constantly negotiating changes in their internal state and their external conditions. Part of Constructive development assumes that organisms inherit both biological traits but also learned knowledge from their progenitors (parents) as well as modifications to the environment partly made by their progenitors (parents). This can be summed up in the phrase “organism is both subject and object of its evolution.” (see: The Dialectical Biologist by RC Lewontin and Richard Levins).

Embodiment–in layman’s terms, the personified or incarnated form of an idea. NZ Suékama uses this term as a merger of material analysis and critical theory. She uses it to describe how forms of metabolic life-activity become “embodied” or associated with particular roles or positions in societies and vice versa. NZ Suékama’s definition of embodiment draws from Marxist feminist thought that views the reproduction of human bodies as both a social and ecological question, not merely biological. NZ Suékama also draws heavily from Sylvia Wynter thought, understanding that self-concept, myths, and language play a central role in the social reproduction process. (see: What Will Be The Cure?–An Interview With Sylvia Wynter and Bedour Alagraa & see: “Social Reproduction Theory,” Social Reproduction, and Household Production by Kirstin Munro)

Endogenous–when something emerges internal to something else. Refers to any phenomenon, resource, data, object that is emerging or is discernible within the context of a given biological, social, or other kind of system and process. Very common in transgender healthcare, to refer to hormones produced within the body. In NZ Suékama’s body of work, “endogenous” is a transfeminist interpretation of “internal evolution” as described by decolonial Marxists like Walter Rodney (see: Against Sex Class Theory, pt 1 & see: How Europe Underdeveloped Africa)

Exogenous–when something emerges external to something else. Exogenous refers to phenomenon, resource, data, object that is introduced to a biological, social, or other kind of system and process from without. Very common in transgender healthcare to refer to hormones introduced to the body. In NZ Suékama’s body of work, “exogenous” is a transfeminist interpretation of “external factors” that influence societal evolution as described by decolonial Marxists like Amilcar Cabral (see: The Weapon of Theory and see: Dispatches from Among the Damned–On the History and Present of Trans Survival)

Imbrication–literally means “overlapping at the edges.” Fish scales, shingles on a roof, the tips of an asparagus, and some flower petals are arranged through imbrication. In NZ Suékama’s body of work, the dominant system is arranged in relation to pre-existing systems through imbrication. This means the relations of the colonial-bourgeois and State system “overlap” at the site of more marginal social forms. Imbrication is a dynamic process that anchors the production and reproduction of the dominant system. NZ Suékama derives imbrication theory from theories of “interlocking domination” in Black feminism (see: scholarship on Triple Jeopardy & the Third World Women’s Alliance)

Metabolic–in Marxist theory, this refers to exchanges between human organic matter and the inorgic conditions of their lives. Analyses of metabolic “life-activity” drew on natural science insights, but was at its core a materialist social science. Marx grounds this socio-ecological perspective in his analysis of labor. For NZ Suékama, socio-ecological metabolism organized and disorganized by the valency of nexing-forms; this stabilizes the nature plus nurture dynamics of the labor process and other relations. (see: works of John Bellamy Foster & see: Ariel Salleh–Ecofeminism as Politics: Nature, Marx, and the Postmodern)

Mutability–refers to the tendency of something to change. In Oyèrónkẹ́́ Oyĕwùmí’s body of work, mutability exists when constructions of gender are globally considered. Yet, at a region level, mutability only exists if gender is constructed as such within a specific culture. In the West, she argues, bioreductive basis for social construction limits mutability. (see: The Invention of Women–Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses)

Nexus–refers to a connection (or series of connections) that links two or more things. In NZ Suékama’s body of work, some social forms are “nexings” of human embodiment in the local material and power structure. For NZ Suékama, these “nexuses” stabilize or anchor how one’s position in the mode of production and patterns of (social) reproduction is negotiated or navigated. She derives the “nexus” hypothesis from Sanyika Shakur’s notion of a “good ole boy network” (see: Pathology of Patriarchy)

Ontogeny–the biological study of an organism’s development. Focuses on the entire lifespan of the individual, including its relations to parents/kin. In Frantz Fanon’s body of work, Freudian psychology applies ontogeny to the person’s consciousness and individual mental/emotional health (see: Black Skin, White Masks)

Phylogeny–the biological study of a species or group of organism’s evolution. Focuses on the diversification of characteristics and relations between and within taxa. In Frantz Fanon’s body of work, Social Darwinism theory applies phylogeny to a classification of human societies (see: Black Skin, White Masks)

Racial-Class Paternalism–refers to a binary view of sexual threat and sexual victimhood which is used to uphold Monogamy, the Nuclear Family, and Cishetero-patriarchy. Typically racial-class paternalism is framed in xenophobic terms, directed at religious minorities, poor/underclass folks, disabled folks, political dissidents, etc but is especially weaponized against trans/queer people (see: Racial-Class Paternalism and the Trojan Horse of Anti-transmasculinity)

Reductionism–reductionist methods take a complex whole and split it into the parts that make it up. Reductionist sciences strive to understand the dynamics of a whole by focusing on the properties/qualities of one or a few of its parts. But not every phenomenon can be understood in this way, especially social issues (like oppression). When it is assumed that all realities can be examined through a reductionist method, this is known as the reductionist worldview. This worldview was especially popularized because of Descartes. (see: The Dialectical Biologist, RC Lewontin and Richard Levins)

Spandrel–in architecture, a “spandrel” is used to describe any feature of a built object which does not serve a purpose, but rather is a simple consequence or result of the design needs and the developmental process. In the work of biologist Stephen Jay Gould, the term “spandrel” is applied to biology, to describe traits in an organism or species which did not evolve as adaptations nor can be said to serve a particular function, but rather came about as a byproduct or consequence of the structural development. A “spandrel” in this context can be used to illustrate certain nonadaptive features of biology, and is applied to certain social realities that mainstream sciences often incorrectly blame on “natural selection,” to challenge the idea that certain societal features, particularly capitalist ones, are adaptations. (see: Critical Human Ecology–Historical Materialism and Natural Laws)

Sociogeny–the study of socio-cultural phenomena. Focuses on both myths/consciousness and politico-economic configurations of the body. In Frantz Fanon’s body of work, sociogeny should be used to clarify relations between colonizer and colonized. In Sylvia Wynter’s body of work, sociogeny can clarify all human environmental relations (see: Towards the Sociogenic Principle & see: Sylvia Wynter—On Being Human as Praxis)

Transect–a straight line across an expanse of ground used to take ecological measurements, continuously or at regular intervals. In Anarkata thought, transfeminism is central to “transecting” Black gender struggles under racial capitalism. This is done by merging Sylvia Wynter’s analysis of humanism with Afropessimist theories of ungendering derived from Hortense Spillers (see: Anarkata–A Statement)

Truncate–means “to cut down” or “to cut short.” In NZ Suékama’s body of work, “truncation” describes the exact tactics, strategies, and methods used both ideologically and practically to disorganize and then reorganize human metabolic life-activity under the valence of the dominant Nexus. She theorizes three continuums of truncation (parallel, lateral, vertical) that are involved in the substitution of non-dualist “nexing-forms” with a dualist nexing-form. At the global level, truncation is a gradual process; at the regional level, truncation is an open & contested process. (see: Nexus Hypothesis–An Introduction series on prezi dot com)

Valency–in chemistry, refers to ability of an atom (or group of chemically bonded atoms) to either replace or form chemical bonds with other atoms (or group of chemically bonded atoms). In NZ Suékama’s body of work, valency describes how a Nexus (or nexing-form) “anchors” the organization of human metabolic activity. Each given society has one or several nexuses that exhibit different valences, although in some instances two or more nexuses may be co-valent. The combining and displacing power exhibited by these nexuses vis-a-vis a given set of socio-ecological questions is not spatiotemporally invariant in its character. Thus, a single nexus may not necessarily exhibit its combining and displacing power in the same way for every feature of a given society, or in the same way for all societies. Thus, while the combining and displacing power of one or several nexuses stabilizes nature-nurture and historical material dynamics in a given context, it is not a closed process. (see: Nexus Hypothesis–An Introduction series on prezi dot com)