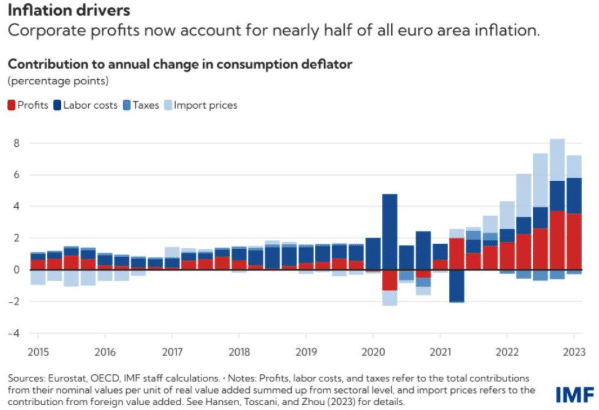

Corporate profits have been the biggest contributor to inflation in Europe since 2021.

This is according to a study published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

“Rising corporate profits account for almost half the increase in Europe’s inflation over the past two years as companies increased prices by more than spiking costs of imported energy”, wrote IMF economists this June.

The IMF said “companies may have to accept a smaller profit share if inflation is to remain on track to reach the European Central Bank’s 2-percent target in 2025”.

IMF economists Niels-Jakob Hansen, Frederik Toscani, and Jing Zhou detailed their findings in a research paper, “Euro Area Inflation after the Pandemic and Energy Shock: Import Prices, Profits and Wages”.

They found that domestic profits were responsible for 45% of the average change in consumption deflator (inflation) from the first quarter of 2022 to the first quarter of 2023, whereas rising import prices contributed 40%.

Some of the main factors contributing to rising import prices have included supply-chain disruptions due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and Western sanctions on Russia—one of the world’s leading producers of oil, gas, fertilizer, and wheat—which caused a big spike in global commodity prices.

However, the share of inflation caused by import prices reached its peak in mid-2022 and has since been falling.

This suggests that post-pandemic supply-chain problems have largely been solved, and some commodity prices have dropped. But corporations have continued hiking prices anyway.

The IMF economists noted that “the results show that firms have passed on more than the nominal cost shock, and have fared relatively better than workers”.

Rising corporate profits were the largest contributor to Europe’s inflation over the past two years as companies increased prices by more than the spiking costs of imported energy. https://t.co/iEf6Emu0Rp pic.twitter.com/HYulCZgb8p

— IMF (@IMFNews) June 26, 2023

Many neoliberal economists and Western central bank officials have ignored the rise in corporate profits, however, and instead blamed inflation on workers’ wages.

In response to the inflation that shot up as the world came out the pandemic, the European Central Bank and U.S. Federal Reserve have been aggressively raising interest rates, at a speed not seen since the Volcker Shock of the 1980s.

Fed chair Jerome Powell admitted that his goal is to “get wages down”.

Former U.S. Treasury Secretary and World Bank chief economist Larry Summers called for five years at 6% unemployment or a year at 10% unemployment in order to bring down inflation.

They put the blame largely on workers, overlooking how companies have exploited a time of uncertainty to make a killing.

Economist Isabella Weber was correct about ‘sellers’ inflation’

Perhaps the most vocal economist in calling for her discipline to research how corporations have contributed to inflation in the past two years is Isabella M. Weber.

A professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Weber has dubbed this “sellers’ inflation”.

Yet, while her work is meticulously sourced, Weber has faced harsh criticism from neoliberal economists.

In December 2021, she published an op-ed in The Guardian titled “Could strategic price controls help fight inflation?”

In the debates around inflation, “a critical factor that is driving up prices remains largely overlooked: an explosion in profits”, Weber wrote.

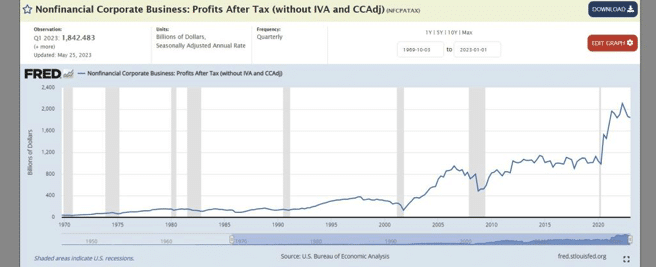

In 2021, U.S. non-financial profit margins have reached levels not seen since the aftermath of the second world war. This is no coincidence.

She noted that “large corporations with market power have used supply problems as an opportunity to increase prices and scoop windfall profits”.

Weber’s article set off a firestorm, and she was brutally attacked. New York Times pundit Paul Krugman claimed Weber’s call for price controls was “truly stupid”.

In February 2023, Weber published an academic article further explaining the phenomenon: “Sellers’ Inflation, Profits and Conflict: Why can Large Firms Hike Prices in an Emergency?”

The IMF economists in fact cited this Weber article in their own working paper on inflation in Europe.

Rethinking inflation

Contemporary mainstream economists typically discuss three types of inflation: demand-pull inflation, cost-push inflation, and built-in inflation.

Cost-push inflation happens when the prices of inputs used in the production process increase. When the international prices of commodities like oil or gas skyrocket, in response to the war in Ukraine for instance, this contributes to cost-push inflation.

Built-in inflation accounts for expectations that inflation that happened in the past will repeat in the future. Corporations often increase their prices every year, for example, simply because they expect costs to increase, not because they actually did increase (but by doing so, costs do sometimes increase).

However, discussions of inflation among Western neoliberal economists are usually focused on demand-pull inflation.

The godfather of monetarism, infamous right-wing University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman, argued that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”, and specifically consisted of demand-pull inflation:

too much money chasing too few goods.

Friedman was an inspiration for Chile’s fascist dictator Augusto Pinochet, who came to power in 1973 in a CIA-backed military coup against the South American nation’s democratically elected socialist president, Salvador Allende.

Friedman was so fixated on government monetary policy that he essentially argued that cost-push inflation doesn’t exist, claiming it was merely a product of demand-pull inflation.

But this recent IMF study shows that the right-wing, monetarist view of inflation is much too simplistic. Capitalist firms can cause inflation simply by hiking up their profits to unreasonable levels.

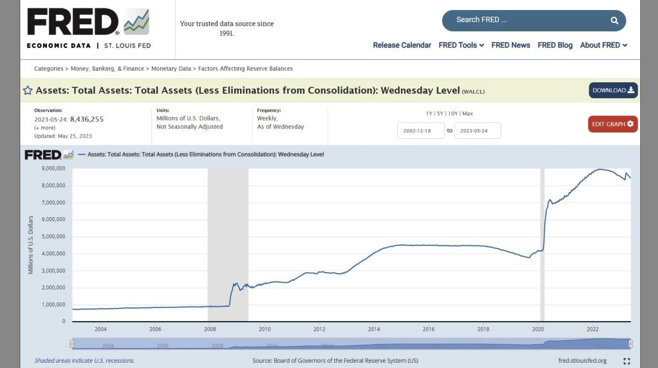

Nevertheless, some monetarist holdovers today still insist that the inflation the world saw following the Covid-19 pandemic was merely caused by central bank money printing.

This fails to explain why there was little consumer price index inflation in the first 12 years of quantitative easing (QE), from 2008 to 2020, before the pandemic hit, and why QE suddenly caused prices to rise only around 2021.

Economist Michael Hudson has pointed out that QE by the U.S. Federal Reserve and European Central Bank in fact fueled asset price inflation, not consumer price index inflation.

In an interview with Geopolitical Economy Report in September 2022, Hudson explained:

The result [of quantitative easing] has been $9 trillion, essentially, of bank liquidity that the Federal Reserve has pushed in.

Now, despite the fact that it is asset price inflation, the fact is that asset price inflation has all occurred on credit.

The asset price inflation has occurred when the Federal Reserve makes basically repo swaps with the banks, enabling the banks to deposit some of their packaged mortgage loans, or bonds, government bonds or even junk bonds, with the Fed.

And they get a deposit with the Fed that enables them to now turn around, as if the Fed was depositing money in the bank like a depositor, letting it lend more, and more, and more for real estate, which has pushed up the price.

Real estate is worth whatever a bank will lend against it. And the banks have been lowering the margin requirements, easing the the terms of the loan.

So the banks have inflated the real estate market, and also the stock and bond market.

The bond market from 2008 today has had the biggest bond rally in history. You can imagine the bond prices going down to below 0%. This is a huge capitalization of the bond rate.

So it has been a bonanza for people who held bonds, especially bank bonds. And it has inflated the top of the pyramid.

But if you inflate it on debt, then somebody has to pay the debt. And the debt, as I just said, is the 90% of the population.

So the fact is that asset price inflation and debt deflation go together, because the wealth part of the economy, the ownership part, has been vastly inflated, the price of wealth relative to labor.

But the debtor part has been has been squeezed by families having to pay much more of their income on mortgages, or credit cards, or student debt, leaving less and less to purchase goods and services.

So if there is a debt deflation, then why do we have a price inflation now? Well, the price inflation is largely a result of the war [in Ukraine], the sanctions that the United States has imposed on Russia.

Russia was, as you know, a major gas exporter, oil exporter, and also the largest agricultural exporter in the world.

So if you exclude Russian oil, Russian gas, Russian agriculture from the market, you’re going to have a shortage of supply, and you’re going to have the prices way up.

So the oil, energy, and food have been a key element.

And also, under the Biden administration and certainly the Trump administration, there has been no enforcement of monopoly prices.

So essentially companies have been using their monopoly power to charge whatever they want.

And even though there wasn’t really a shortage of gas or of oil earlier this year (2022), you had a huge spike in the price, for no other reason than the fact that the oil companies could charge it.

Partly this was done by financial manipulations in the forward markets. The financial markets had bid up the price of oil and gas. But also other companies have.

And right across the board, if you have a company in a commanding position of being able to control the market, you have essentially permitted monopolies to take place.

Well, Biden had appointed a number of anti-monopoly officials that were going to try to impose anti-monopoly legislation. But they’re not supported by the Democratic Party or the Republican Party enough to really empower them to have had much effect so far.