Irrespective of what stance you take on the war in Ukraine, or anywhere else, in March last year, U.S. author Meehan Crist wrote the following in the London Review of Books,

One of the worst outcomes of the war in Ukraine would be an increasingly militarised response to climate breakdown, in which Western armies, their budgets ballooning in the name of “national security” seek to control not only the outcome of conflicts but the flow of energy, water, food, key minerals and other natural resources. One does not have to work particularly hard to imagine how barbarous that future would be.

Crist’s point is simply to describe the world we already have, but a bit more so; and her prediction is exactly what is happening.

- The U.S. has raised military spending to $858 billion this year; up from $778 billion in 2020.

- France has announced an increase from a projected E295 billion to E413 billion in the next seven years (an average of E59 billion a year).

- German spending is rising sharply, from E53 billion in 2021 to E100 billion in 2022 and is set to go further.

- Japan aims to double its military spending by 2028 and is also debating whether to start deploying nuclear weapons.

- In the UK, the government’s aim to increase military spending from 2.1% of GDP to 2.5% by 2030 comes on the back of what is already among the highest per capita military spends in the world.

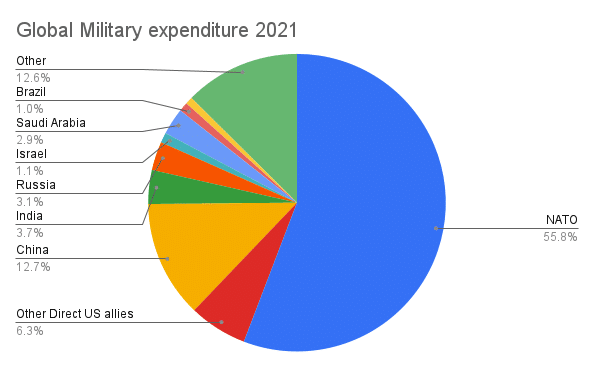

- NATO, the core alliance of the Global North, already accounted for 55.8% of global military spending in 2021 before any of these increases.

- Other direct U.S. allies—with a mutual defence pact—accounted for another 6.3%.

- So, the direct U.S. centred military alliances account for three fifths of global military spending and yet they are now raising it further at unprecedented rates. These are the world’s dominant imperial powers, acting in concert to sustain a “rules based international order” in which the rules are written in, and to suit, the Global North in general and Washington in particular.

The carbon boot print of these militaries is not measured under the Paris Agreement. It is, nevertheless, huge and growing; and we can’t pretend it isn’t. At the moment, the carbon boot print of the U.S. military alone is the same as that of the entire nation of France. This is incompatible with stopping climate breakdown; both in the direct impact of production and deployment, the diversion of funds which are urgently needed to invest in the transition, and the potential impact of their use—which could kill us all very quickly; particularly if nuclear weapons are used. John Bellamy Foster’s Notes on Exterminism for the Twenty First Century Ecology and Peace Movements should be required reading for both movements.

Because this military is not sitting idle. The first phase of the Wars for the New American Century—in the form of the War on Terror since 2001—have been calculated by Browns University at 4.5 million people; three quarters of them civilians killed by indirect impacts of U.S. and allied military interventions. The scale of this is because doctrines like “shock and awe” are not simply an impressive displays of explosive power, but specifically designed to smash energy and water systems, both clean water supply and sewage treatment, within the first twenty four hours of an intervention to reduce surviving civilian populations to a state of numbed misery and demoralisation. “Why do they hate us?” I wonder. 4.5 million people is about half the population of Greater London, or three quarters of the population of Denmark and twenty two times as many as have died in the Ukraine war so far (assuming total casualties of 200,000, most of them military on both sides). It’s a lot of people. *

Their deployment and use more widely against opponents that are more resilient than Iraq, Afghanistan or Libya- which this escalation of expenditure and increased integration of alliances makes possible—would, even if it did not go nuclear, be catastrophic both in its direct loss of lives but also in the disruption of global supply chains leading to widespread economic unravelling. According to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, a war in the South China Sea that closed down shipping lanes would have a rapid impact regionally—“Taiwan’s economy would contract by a third, while Singapore’s economy would fall by 22%, according to the baseline estimate. Hong Kong, Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia would suffer falls of between 10% and 15%”—but would have a knock on effect everywhere else affecting 92% of global trade. The attempt in the Global North to set up “secure supply chains”—defining economic policy increasingly around military imperatives (“securonomics”) is not to avert such a conflict, but to make it economically manageable, and therefore more likely.

This scale of military expenditure also dwarfs their domestic investment in combatting climate change, urgently needed because the wealthiest countries put the heaviest weight of emissions on the rest of the world, both historically and through their per capita footprints now: let alone helping Global South countries develop without reliance on fossil fuels. This has a wider implication, with the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network reporting that progress towards the UN Sustainable Development goals has been static for three years.

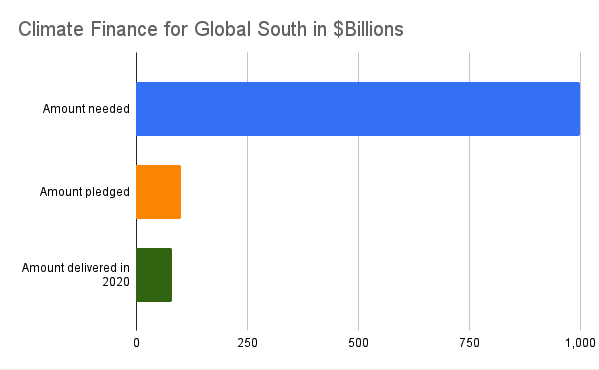

Pledged to commit $100 billion a year to help the transition in the Global South, more than ten years ago, they have never been able to eke out this money, have never hit the target, have tried to use loans (debt trap) instead of transfers, sought to apply conditions and control. The U.S. contribution to that is now aiming for just over $11 billion by 2024. This is now reckoned to be a tenth of what’s needed. This is despite 66% of their populations agreeing that this support should go in, and only 11% against. The contrast with the $77 billion they have stumped up to fight the Ukraine war with no trouble at all in the last year is quite startling. News that Finland is planning to cut development aid to countries in Africa that don’t line up behind the Western line on Ukraine is an ominous sign of how far backwards this could begin to go; with any attempt at global governance through structures like the UN abandoned and notions of international obligation and mutual humanity giving way to even more overtly colonial attitudes and practices than we already have. Although the notion that the Global North can “build a wall” and keep the human consequences of climate breakdown out is a fantasy—as the climate is breaking down behind the wall too—it probably won’t stop them trying.

The USA and its allies pose themselves as “Global Leaders”. They could and should be, as they are the countries with the greatest concentrations of wealth, power and technical know how, communications and education, but they are falling horribly short; because they see leadership as the same thing as dominance—and subordinate everything else to that.

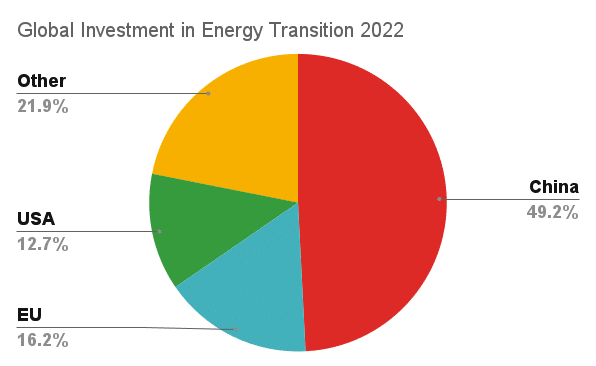

In fact, in 2022, China—usually presented in our media as a negative force on climate—invested 70% more in renewable energy generation than the USA and EU combined, just under half the global total on its own. Next year, according to the International Energy Agency, China will account for 70% of new offshore wind, 60% of new onshore wind, and 50% on new solar PV installations. So, the “international leaders” have a lot of catching up to do.

The U.S. and EU are some way behind, and nowhere near where they need to be. Instead of investing on the scale needed to hold the global temperature increase below 1.5C, they are tooling themselves up militarily to try to deal with the consequences of failing to do so; in an effort to sustain their global dominance. If they are leading us anywhere, its to Armageddon.

A report from the U.S. military in 2019 sums up the paradox. Reflecting that, if climate breakdown continues at its present rate, countries that are already water stressed will be getting beyond crisis point within two decades and that this will lead to “disorder”. Their conclusion was that this means that:

- they will be intervening in these crises, and

- will therefore need to build themselves in a secure supply chain of water so that the troops who are dealing with people in crisis because their environment has run out of it, will have enough to keep them going in the field!

Reflecting further, that on our current trajectory, climate impacts within the United States itself would lead to infrastructure breaking down, followed by the social order breaking down, followed by the military itself breaking down; as it faced overstretch trying to maintain order as civil society failed. Nevertheless, they also note that the rapidly increasing melt of the Arctic ice shelves and permafrost means that new sources of the fossil fuels that are causing the crisis in the first place to be available for exploitation and that a key task for them would be to make sure that the U.S. gets the lion’s share of them. As a study in self defeating thinking, it can’t be beat.

To repeat the point at the beginning, regardless of anyone’s stance on any given war taking place now, and who should “win” it, its this drive and acceleration of military spending that the climate and peace movements should be combining to hold back—both to avert the growing risk of conflict, because arms races tend to end in wars on the momentum of their own dynamic (which requires a lot of demonisation and conflictual stances to fuel and justify it) and to allow saved funds to be used to avert the climate crisis itself. A bottom line demand is that the military carbon boot print must be accounted for in the Paris Process and a mechanism agreed for reductions to a common per capita level, combined with common measures and investments for increased global cooperation in lock step with it.

*Casualty figures in Ukraine are easy to come by but hard to trust. 200,000 assumes a parity between the Ukrainian and Russian militaries; whereas figures from Mossad, among others, indicate significantly lower Russian losses (at perhaps a fifth to a third of the Ukrainian level) so 200,000 may be a high estimate. One notable feature of this war is that civilian casualties have been a fraction of the military losses—the opposite of the trend from the mid twentieth century onwards; during which “there has been an increase in civilian fatalities from 5% at the turn of the 19th century to 15% during World War I (WW I), 65% by the end of World War II (WW II), and to more than 90% in the wars during 1990’s, affecting more children than soldiers”. From https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2021.765261/full#B12