Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

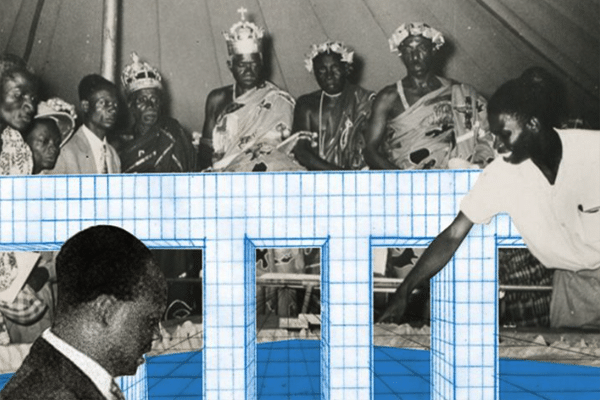

The Akosombo Dam in the Volta River, inaugurated in 1965 during Kwame Nkrumah’s presidency.

In June, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Solutions Network published its Sustainable Development Report 2023, which tracks the progress of the 193 member states towards attaining the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). ‘From 2015 to 2019’, the network wrote, ‘the world made some progress on the SDGs, although this was already vastly insufficient to achieve the goals. Since the outbreak of the pandemic in 2020 and other simultaneous crises, SDG progress has stalled globally’. This development agenda was adopted in 2015, with targets intended to be met by 2030. However, halfway to this deadline, the report noted that ‘all of the SDGs are seriously off track’. Why are the UN member states unable to meet their SDG commitments? ‘At their core’, the network said, ‘the SDGs are an investment agenda: it is critical that UN member states adopt and implement the SDG stimulus and support a comprehensive reform of the global financial architecture’. Yet, few states have met their financial obligations. Indeed, to realise the SDG agenda, the poorer nations would require at least an additional $4 trillion in investment per year.

No development is possible these days, as most of the poorer nations are in the grip of a permanent debt crisis. That is why the Sustainable Development Report 2023 calls for a revision of the credit rating system, which paralyses the ability of countries to borrow money (and when they are able to borrow, it is at rates significantly higher than those given to richer countries). Furthermore, the report calls on the banking system to revise liquidity structures for poorer countries, ‘especially regarding sovereign debt, to forestall self-fulfilling banking and balance-of-payments crises’.

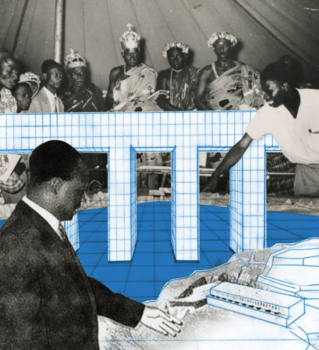

The TAZARA Railway (or Uhuru Railway), connecting the East African countries of Tanzania and Zambia, was funded by China, constructed by Chinese and African workers, and completed in 1975.

It is essential to place the sovereign debt crisis at the top of discussions on development. The UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimates that ‘the public debt of developing countries, excluding China, reached $11.5 trillion in 2021’. That same year, developing countries paid $400 billion to service their debt – more than twice the amount of official development aid they received. Most countries are not borrowing money to invest in their populations, but to pay off the bondholders, which is why we consider this not financing for development but financing for debt-servicing.

Reading the UN and academic literature on development is depressing. The conversation is trapped by the strictures of the intractable and permanent debt crisis. Whether the issue of debt is highlighted or ignored, its existence forecloses the possibility of any genuine advance for the world’s peoples. Conclusions of reports often end with a moral call – this is what should happen – rather than an assessment of the situation based on the facts of the neocolonial structure of the world economy: developing countries, with rich holdings of resources, are unable to earn just prices for their exports, which means that they do not accumulate sufficient wealth to industrialise with their own population’s well-being in mind, nor can they finance the social goods required for their population. Due to this suffocation from debt, and due to the impoverishment of academic development theory, no effective general theoretical orientation has been provided to guide realistic and holistic development agendas, and no outlines seem readily available for an exit from the permanent debt-austerity cycle.

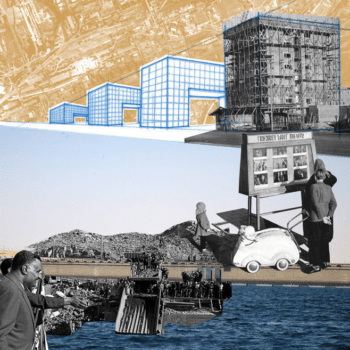

Collage of the Aswan High Dam (Egypt), Bhilai Steel Plant (India), and the Eisenhüttenstadt high-rise housing project (German Democratic Republic).

At Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, we are eager to open a discussion about the need for a new socialist development theory – one that is built from the projects being pursued by peoples’ movements and progressive governments. As part of that discussion, we offer our latest dossier, The World Needs a New Socialist Development Theory, which surveys the terrain of development theory from 1945 to the present and offers a few gestures towards a new paradigm. As we note in the dossier:

Starting with the facts would require an acknowledgement of the problems of debt and deindustrialisation, the reliance upon primary product exports, the reality of transfer pricing and other instruments employed by multinational corporations to squeeze the royalties from the exporting states, the difficulties of implementing new and comprehensive industrial strategies, and the need to build the technological, scientific, and bureaucratic capacities of populations in most of the world. These facts have been hard to overcome by governments in the Global South, although now – with the emergence of the new South-South institutions and China’s global initiatives – these governments have more choices than in decades past and are no longer as dependent on the Western-controlled financial and trade institutions. These new realities demand the formulation of new development theories, new assessments of the possibilities of and pathways to transcending the obstinate facts of social despair. In other words, what has been put back on the table is the necessity for national planning and regional cooperation as well as the fight to produce a better external environment for finance and trade.

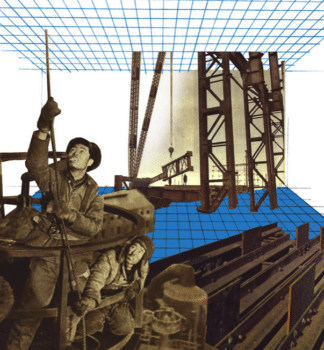

Anshan Iron and Steel Company was renovated and expanded as one of the 156 construction projects in China that was supported by the Soviet Union in the 1950s.

A recent conversation in Berlin with our partners at International Research Centre DDR (IF DDR) led to the realisation that this dossier failed to engage with the debates and discussions around the development that took place in the Soviet Union, the German Democratic Republic (DDR), Yugoslavia, and the broader international communist movement. As early as the Second Congress of the Communist International, held in Moscow in 1920, communists began to formulate a theory of ‘non-capitalist development’ (NCD) for societies that had been colonised and integrated into the capitalist world economy while still retaining pre-capitalist forms of production and social hierarchy. The general understanding of NCD was that post-colonial societies could circumvent capitalism and advance through a national-democratic process to socialism. NCD theory, which was developed at international conferences of communist and workers’ parties and elaborated upon by Soviet scholars such as Rostislav A. Ulyanovsky and Sergei Tiulpanov in journals like the World Marxist Review, was centred on three transformations:

- Agrarian reform, to lift the peasantry out of its condition of destitution and to break the power of landlords.

- The nationalisation of key economic sectors, such as industry and trade, to restrict the power of foreign monopolies.

- The democratisation of political structures, education, and healthcare to lay the socio-political foundations for socialism.

Unlike the import-substitution industrialisation policy advanced by institutions such as the UN Economic Commission for Latin America, NCD theory had a much firmer understanding of the need to democratise society rather than to merely turn around the terms of trade. IF DDR’s ‘Friendship’ series features a powerful recounting of the practical application of NCD theory in Mali during the 1960s in an article written by Matthew Read. IF DDR and Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research will be working on a comprehensive study of NCD theory.

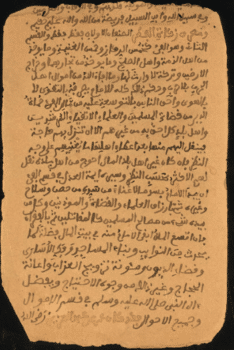

Page from Usul al-‘Adl li-Wullat al-Umur wa-Ahl al-Fadl wa-al-Salatin (‘The Administration of Justice for Governors, Princes, and the Meritorious Rulers’), c. late 1700s.

Prior to colonialism, African and Arab scholars in West Africa had already begun to work out the elements of a development theory. For example, ʿUthman ibn Muhammad ibn ʿUthman ibn Fodyo (1754–1817), the Fulani sheikh who founded the Sokoto Caliphate (1804–1903), wrote Usul al-‘Adl li-Wullat al-Umur wa-Ahl al-Fadl wa-al-Salatin (‘The Administration of Justice for Governors, Princes, and the Meritorious Rulers’) to guide himself and his followers on a path to lift up his people. The text is interesting for the principles it outlines, but – given the level of social production at the time – the caliphate relied on a system of low technical productivity and enslaved labour. Before the people of West Africa could wrest power from the caliphate and drive their own society forward, the last caliph was killed by the British, who – along with the Germans and French – seized the land and subordinated its history to that of Europe. Five decades later, Modibo Keïta, a communist militant, led Mali’s independence movement, seeking to reverse the subordination of African lands through the NCD project. Keïta did not explicitly draw a direct line back to ibn Fodyo – whose influence could be seen across West Africa – but we might imagine the hidden itineraries, the remarkable continuities between those old ideas (despite their saturation in the wretched social hierarchies of their time) and the new ideas that were put forward by Third World intellectuals.

Warmly,

Vijay