Since the overthrow of Niger’s U.S.-friendly government, West African nations of the ECOWAS bloc have threatened an invasion of their neighbor.

Before leading the charge for intervention, ECOWAS chair Bola Tinubu spent years laundering millions for heroin dealers in Chicago, and has since been ensnared in numerous corruption scandals.

Hours after Niger’s Western-backed leader was detained by the country’s presidential guard on July 28, Nigerian President and chair of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Bola Tinubu leapt into action, warning that the group of nations “will not tolerate any situation that incapacitates the democratically-elected government.”

As the Chairperson of ECOWAS… I state without equivocation that Nigeria stands firmly with the elected government in Niger.

Two days later, ECOWAS imposed severe sanctions on Niger, and the bloc issued a stark ultimatum: if the newly-inaugurated junta won’t reinstall the ousted president in a week’s time, the group’s pro-Western African governments will–by military means, if necessary.

On Saturday, July 6–one day before the deadline–ECOWAS leaders approved a plan to invade the country, with the ominous caveat that they are “not going to tell the coup plotters when and where we are going to strike.”

If ECOWAS gets its way, member states Benin, Cabo Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea Bissau, Liberia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Sénégal and Togo will be pressured to send their soldiers to invade Niger.

These developments have thrust the typically-overlooked West African country of Niger into the Western media spotlight. But if hostilities break out, it wouldn’t just be one single impoverished African state in the crosshairs.

Neighboring Burkina Faso, Mali and Guinea, which are also governed by military administrations that recently seized power by force, have all warned that any attack on Niger will be viewed as an attack on them too. If their ECOWAS rivals make the first move, the nations which mainstream media have dubbed Africa’s “coup belt” have pledged to unleash their military forces as well–an announcement which should end any illusions that restoring the country’s previous president would be a painless process.

Leading the pro-Western coalition is the president of its most powerful country, Nigeria: Bola Tinubu. One of Nigeria’s wealthiest men, the source of the scandal-plagued president’s fortune remains unclear.

Documents reviewed by The Grayzone reveal Tinubu as a longtime U.S. asset who was named as an accomplice in a massive drug running operation that saw him launder millions on behalf of a heroin-dealing relative.

I had a great time with other Heads of State and important dignitaries at the State Banquet hosted by President Emmanuel Macron in Paris, France, this evening. President Macron and his wife, First Lady Brigitte Macron were both gracious and warm, making the event a very pleasant… pic.twitter.com/lTHTZfTIMC

— Bola Ahmed Tinubu (@officialABAT) June 22, 2023

Bola Tinubu’s career marred by drug-trafficking, corruption allegations

For over 30 years, Bola Tinubu has been a major force in Nigeria’s political scene and the country’s economy, with local nicknames ranging from “the Mother of the Market” to “the Godfather of Lagos” and “the Lion of Bourdillon.” But his power inside Nigeria went largely unnoticed by international audiences until 2023, when he became ECOWAS chair after winning the presidency in an election closely tracked by the U.S. government.

As president, Tinubu quickly instituted a regime of economic reforms backed by the U.S.-controlled International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Over the course of Tinubu’s political career in Nigeria, the African operator has cultivated a close relationship with the U.S. embassy. According to a slew of classified State Department cables released by WikiLeaks, American officials relied heavily on Tinubu’s assessments of the domestic political landscape.

The ECOWAS chair’s early life is shrouded in mystery, and even his exact age is unknown. Nearly every detail of Tinubu’s personal history–prior to his appearance in Chicago on a student visa–is in dispute, including his legal birth name.

Records from Chicago State University show that Tinubu received a degree in Business Administration in 1979. In the following years, media reports indicate that Tinubu was employed in some capacity at a number of major U.S.-based multinationals, including Mobil Oil Nigeria, consulting firm Deloitte, and GTE, which was the largest communication and utilities company in the U.S. at the time.

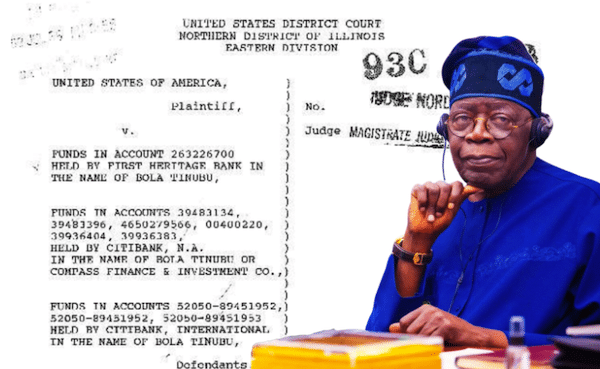

Of the few details about the Nigerian President’s early exploits which can be confirmed, many are derived from a 1993 court docket naming Tinubu as an accomplice in a massive midwestern drug smuggling operation.

As journalist David Hundeyin has detailed, court documents from the U.S. District Court’s Northern District of Illinois make it clear that Tinubu amassed a small fortune laundering money for a heroin-trafficking relative in Chicago, and that U.S. government officials ultimately seized well over a million dollars from various bank accounts registered under the current Nigerian president’s name.

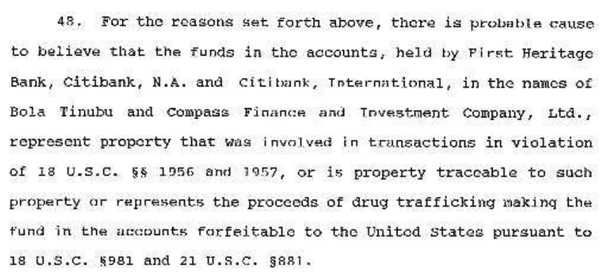

A 1993 report by IRS Special Agent Kevin Moss explained that “there is probable cause to believe that funds in certain bank accounts controlled by Bola Tinubu… represent proceeds of drug trafficking; therefore these funds are forfeitable to the United States.”

In the documents, Moss describes an extremely close working relationship between the future Nigerian president and two Nigerian heroin dealers named Abiodun Olasuyi Agbele and Adegboyega Mueez Akande, the latter of whom was listed as Tinubu’s cousin on an application for a vehicle loan.

“According to bank employees, when Bola Tinubu came to First Heritage Bank in December 1989 to open the accounts, he was introduced to them by Adegboyega Mueez Akande, who at that time maintained an account at the bank.” What’s more, bank records indicate that “Bola Tinubu also opened a joint checking account in his name and the name of his wife, Oluremi Tinubu,” who had “previously opened a joint bank account also at this bank with Audrey Akande, the wife of Adegboyega Mueez Akande,” Moss explained. In several of the applications, the addresses used by Tinubu exactly matched those previously used by Akande.

“According to bank records… Tinubu opened an individual money market account and a NOW account” at First Heritage Bank in December 1989, the special agent noted. “In the application, Tinubu stated that his address was 7504 South Stewart, Chicago, Illinois” —

the same address used previously by Akande.

“Bank records disclosed that five days after the account was opened, on January 4, 1990, $80,000 was deposited into the NOW account at First Heritage Bank by wire transfer through First Chicago from Banc One Houston,” the report continues. According to the IRS, the money was sent by Akande.

But the Nigerian president’s financial dealings with the heroin traffickers went even further, according to the IRS special agent. He wrote that Citibank records documented “two additional corporate accounts held in the name of Compass Finance and Investment Company, Ltd. which were controlled by Bola Tinubu.”

“When Bola Tinubu opened these accounts,” he provided “a memorandum of association and articles of association” which “identified Mueez Adegboyega Akande and Abiodun Olasuyi Agbele as directors of Compass Finance and Investment Company, Ltd.,” Moss wrote.

In the end, Tinubu somehow managed to deposit over $660,000 in his First Heritage Bank account in 1990, and more than $1.2 million the next year–all while claiming to take home just $2,400 a month from his position at Mobil Oil Nigeria.

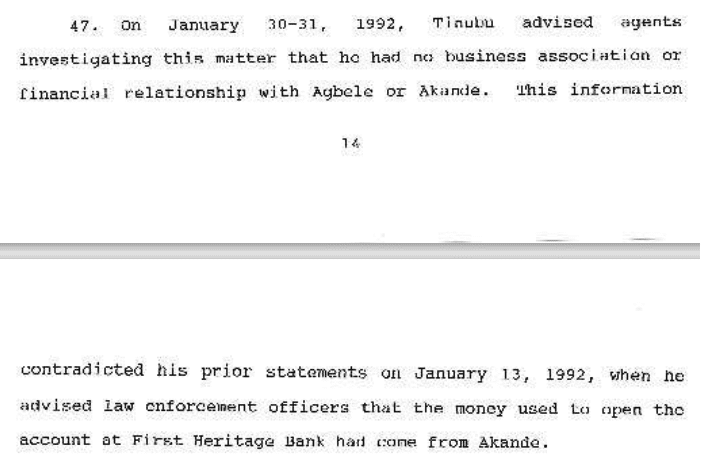

As the investigation into the money laundering scheme began to gain traction, Tinubu left the U.S. and returned to Nigeria. Ultimately, Moss was able to speak to Tinubu by telephone on a number of occasions, and the special agent reported that the future president initially acknowledged his personal and financial dealings with the pair of drug traffickers.

But in late January of 1992, “Tinubu advised agents investigating this matter that he had no business association or financial relationship with Abele or Akande,” Moss wrote.

This information contradicted his prior statements on January 13, 1992, when he advised law enforcement officers that the money used to open the account at First Heritage Bank had come from Akande.

Back in Nigeria, Tinubu had already begun to transition into the political arena. By 1992, he’d been elected to the Senate, and in 1999 he became the Governor of Lagos State, a position he retained until 2007. At some point in his tenure, Tinubu established a relationship with the U.S. Embassy which would last for years to come, according to a trove of diplomatic cables released by Wikileaks.

But even his State Department allies couldn’t help noticing Tinubu’s penchant for dishonesty. One particularly noteworthy cable pointed out that the politician was “known to play fast and loose with the facts” and “has been caught in the past embellishing his educational achievements.”

In the end, however, Tinubu’s usefulness seemed to outweigh his casual relationship with the truth, and the future Nigerian president went on to provide American officials with a near-continuous assessment of the political situation in his country. One typically intimate meeting with Tinubu ended with the U.S. ambassador to Nigeria commenting:

as always, we found his take on the national political scene to be insightful.

When the cables came to light in 2011, many Nigerians were shocked at the candor with which their elected officials spoke to Washington’s envoys. “The willingness of our elites to divulge unsolicited information about the nation to U.S. officials betrays an infantile thirst for a paternal dictatorship,” Nigerian-American professor and columnist Farooq Kperogi wrote.

Though Tinubu appeared to have escaped justice for his alleged role in a heroin trafficking conspiracy, accusations of corruption would continue to dog the ECOWAS chair throughout his political career in Nigeria. Since leaving office as governor of Lagos in 2007, Tinubu “picked every subsequent winning candidate,” according to German broadcaster DW, which noted earlier this year that the tycoon “is believed to be one of Nigeria’s richest politicians but the source of his wealth is unknown.”

In recent years, clues about the origins of the fortune amassed by one of Africa’s leading political players have begun to come to light.

In 2009, Tinubu came under investigation by the Metropolitan Police of London, who were probing allegations that the politician had pooled money with two other Nigerian governors to create a front company known as the “African Development Fund Incorporation.”

Investigators alleged the unusual business arrangement was actually a joint effort to illegally acquire shares of ECONET, a telecommunications firm founded by US intelligence asset and Gates Foundation trustee Strive Masiyiwa. But attempts to probe the legitimacy of the transactions in question were sidelined when the Nigerian federal government stonewalled the British investigation, which ultimately concluded without a single arrest. To this day, Nigerian authorities have yet to release the evidence requested by UK authorities.

In 2011, Tinubu was tried before the Code of Conduct Tribunal in Nigeria for illegally operating 16 foreign bank accounts. Eager to avoid the embarrassment he’d previously suffered when being photographed in court, the ECOWAS chair reportedly refused to take his place at the dock in a judicial hearing.

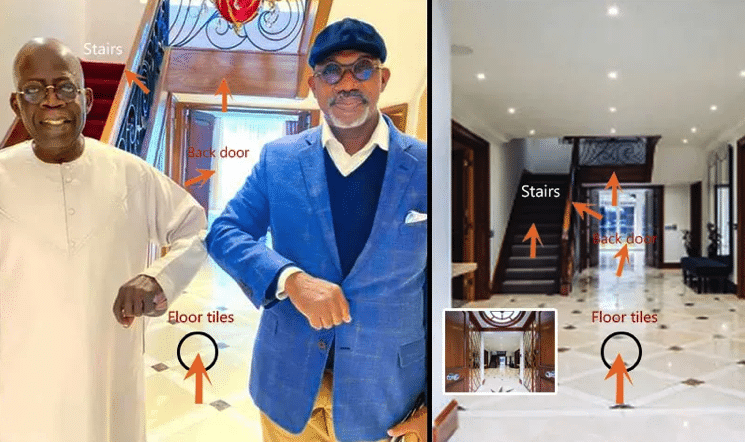

But the unwelcome attention appears to have done little to rein in the politician’s extravagant taste, and Tinubu once again found himself embroiled in a corruption scandal following an investigation into the luxurious 7,000-square foot mansion where the Nigerian president stays when receiving medical care in London.

Tinubu inside his London mansion with a Nigerian governor, Dapo Abiodun (Photo: Premium Times).

According to Nigerian outlet Premium Times, the massive villa in London’s exclusive Westminster borough was picked up for a song by Tinubu’s son, who somehow managed to purchase the property at a discount of approximately $10 million from a wealthy fugitive—even though the seller’s assets, including the mansion in question, had been frozen by a Nigerian court. Photos published on social media in 2017 show Tinubu posing inside the villa alongside Nigeria’s president at the time, Muhammadu Buhari.

The current and previous president worked closely for decades, and Tinubu has publicly claimed sole credit for Buhari’s presidency while campaigning. “If it were not for me standing before you leading the army, saying ‘Buhari, go ahead, we’re behind you,’ he could never have become the president,” he told supporters at a rally last year.

But the suspicious confluence of money and influence didn’t end with the mysterious mansion in London. During Nigeria’s 2019 general election, footage of armored trucks entering Tinubu’s residence went viral on social media, and the incident was widely seen as proof that the politician was engaged in a fraudulent vote-buying scheme. But Tinubu remained defiant, telling reporters,

I keep money wherever I want.

“Excuse me, is it my money or government money?” he asked. “If I don’t represent any agency of government and I have money to spend, if I have money, if I like, I give it to the people free of charge,” he insisted.

This January, the official explanation for the episode evolved again when one of his party’s representatives told a Nigerian TV station that the armored trucks in question had simply “missed [their] way” and arrived at the wrong address. Asked why Tinubu had seemingly admitted to dispensing cash to the public, the party’s organizing secretary in Lagos offered the bemused presenters an equally improbable explanation:

he said that jokingly.

ECOWAS as a neocolonial weapon

While ECOWAS was officially founded via the Treaty of Lagos in 1975, its official history notes the bloc’s origins date back to the creation of the CFA Franc in 1945, which consolidated France’s West African empire into a single-currency union. Publicly, the move was described as a benevolent attempt to shield these colonies from the consequences of the French franc’s sharp devaluation in 1945, following the creation of the U.S.-dominated Bretton Woods system. As the French finance minister said at the time:

In a show of her generosity and selflessness, metropolitan France, wishing not to impose on her faraway daughters the consequences of her own poverty, is setting different exchange rates for their currency.

In reality, the introduction of the CFA Franc meant that Paris was able to maintain highly unequal trading relationships with its African colonies, at a time when its economy was ravaged by World War II and its overseas empire was rapidly disintegrating. The currency made it cheap for member states to import from France and vice versa, but prohibitively expensive for them to export anything anywhere else.

This forced dependency in Francophone West Africa created a captive market for the French, and by extension the rest of Europe. That dynamic, which has stunted regional economic development for decades, persists to this day. The CFA Franc’s continued dominance ensures West African states remain under the economic and political control of France. Those African nations are powerless to enact meaningful policy changes, as they lack control over their own monetary policy.

That the currency features so prominently in the authorized history of ECOWAS is instructive, because the bloc has long-been criticized as an extension of French imperialism. It was not for nothing that in 1960, then-French President Charles de Gaulle made membership of the CFA Franc a precondition for decolonization in Africa.

Though ECOWAS is theoretically meant to maximize member states’ collective bargaining power by fostering “interstate economic and political cooperation,” such harmonization makes it easier for former imperial powers like France to exploit and enfeeble their constituent countries. The bloc imposes a strict, Western-approved legal and financial framework upon its members, and any state deviating from these rules is harshly punished.

In January 2022, ECOWAS imposed strict sanctions on Mali, prompting thousands to take to the streets in support of the military government that seized power in January the previous year. The new government’s efforts to purge the country of malign foreign influence saw a complete ban on French media imposed, a decision which was slammed by the UN but cheered by average Malians.

ECOWAS applied similar measures to Burkina Faso in response to a September 2022 military coup, which saw Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba removed after just eight months in power. Though Damiba himself seized via military coup, there was little condemnation from Western officials and few suggestions that ECOWAS impose sanctions–perhaps due to the ousted leader’s pro-Western orientation and status as a graduate of multiple elite U.S. military and State Department training courses.

Since 1990, ECOWAS has waged seven separate conflicts in West Africa, in order to protect the West’s preferred despots across the region. Meanwhile, between 1960 and 2020, Paris launched 50 separate overt interventions in Africa. Figures for clandestine activities conducted during this time are unavailable, but the country’s fingerprints are plastered all over multiple rigged elections, coups, and assassinations that have sustained compliant, corrupt governments in power throughout the continent.

As President Jacques Chirac remarked in 2008, “without Africa, France will slide down into the rank of a third [world] power.” This perspective was reaffirmed in a 2013 French Senate report, Africa is Our Future. Indeed, the mere existence of anti-imperialist governments anywhere in the region is intolerable to Paris.

Luckily for the French elite, compromised figures like Bola Tinubu are still on hand to do their dirty work for them.