High up in Venezuela’s Andes, the township of Mucuchies is home to a campesino-led initiative striving for sustainable agricultural production. Integral Producers of the Highlands [PROINPA, for the organization’s Spanish-language name] is widely recognized not only for its top-notch seed potatoes but also for its scientific initiatives such as a state-of-the-art seed lab, a germplasm bank, and, most recently, an aeroponic seed production facility.

One of the secrets to PROINPA’s success is its democratic organization and emphasis on education. Founded 24 years ago, the organization’s structure has an assembly of associated producers as its topmost level of decision-making. That is, at PROINPA, it is the producers themselves who are in charge. These associates are all hard-working campesinos but have also achieved high levels of formal education. Many have doctorates or masters, and all have gone through educational processes centered on the science and sustainability of food production.

PROINPA’s core mission of food sovereignty is of strategic importance to a country under siege. The organization pursues this goal by promoting agroecology, crop diversification, endogenous scientific development, and a new social organization of production.

PROINPA’s origins and its life-centered mission

The organization’s history as told by its founders and associates.

Caroly Higuera is an agricultural engineer with a PhD in Human Development and a PROINPA founder | César Mesa is a potato producer and a PROINPA founder | Gerardo (Lalo) Rivas Gil is a potato producer and a PROINPA associate. He is currently the organization’s General Coordinator and a spokesperson for El Paso de Bolívar 1813 Commune | José Gregorio Gil Pérez is a campesino and a PROINPA associate | Julio Orlando Mora Parra is president of ASOCRAMR, an association of irrigation committees, and a potato producer | Marisol Montilla is part of PROINPA and works as Field Technician for the Optimization of Processes | Rafael Romero is an engineer and PROINPA associate and founder, instrumental in creating and maintaining the organization | Richard Rivas is a PROINPA associate producer and founder | Vladimir Balza is a campesino, a PROINPA associate, and the president of the Misintá Irrigation Committee (Voces Urgentes)

Caroly Higuera: A quarter century ago, in 1999, twenty-five small and mid-size producers in Mérida’s highlands got together with one goal: improving agricultural processes. All this was to be done through science and a philosophy of sustainable development. That’s how PROINPA was born.

Our mission has remained the same since those early days, but we have grown considerably. Now we have CEBISA [a biotechnological center] with its state-of-the-art in vitro seed lab, a germplasm bank [a collection of live plant matter for the preservation of biological diversity and food security], and four greenhouses, one of them for aeroponic seed potato production. We also have a silo for potato storage and several farms have become research sites.

While the epicenter of the organization continues to be Mucuchies, we are now working in 18 states to promote the diversification of campesino production, sustainability, and seed sovereignty.

Gerardo (Lalo) Rivas Gil: PROINPA brings together the work and dreams of many people, but Rafael Romero is the key figure in our organization. Years ago, many of us were brought together by the Belgian Andes Tropicales NGO, which promoted sustainability. When that project came to an end, Rafael called us and said: “We must organize and keep working together.” That’s exactly what happened.

I’m a campesino from a long line of potato growers, but I’m also a scientist of sorts. How did that happen? PROINPA is committed to the education of producers like me. I can safely say that PROINPA represented a turning point in my life. Our collective practices, monthly assemblies, workshops, conversations and debates–all that has changed the way I understand food production in a world that commodifies everything.

At PROINPA we are campesinos and scientists, and we are teachers too. Those three roles come together in the organization. That’s what makes it such an extraordinary project. Many have doubted the capacity of a handful of campesinos to do such things. They ask: Can these rough-around-the-edges producers operate a top-notch lab? Can they really improve the quality of seeds? Will they be able to do it on their own?

The answer to all these questions is yes. It hasn’t been easy, we’ve had to study a lot, we’ve worked hard, and there has been a great deal of sacrifice in all of it… Yet, it’s been worth it. Today PROINPA is a flagship project in the country. Moreover, in these times of imperialist blockade, our work caring for and improving seeds is all the more important.

Carlolys Higuera: PROINPA is a reflection of us, the people who built it. Together with its virtues and flaws, the association has grown. It now produces yearly an average of 500 thousand pre-basic* seed potatoes in 20 varieties: some for consumption, some for agroindustry, and some for processing to extract starch.

We do this in our state-of-the-art CEBISA facilities, while we promote non-conventional practices and a sustainable scheme that guarantees that our children and grandchildren will be able to go on producing bycombining hard science with a philosophy centered on life.

Rafael Romero: Technically you can produce without agrochemicals, without fertilizers, and even without soil, but you can’t produce without seeds. As a country, we are very vulnerable when it comes to seed production. In fact, most of the seeds come from abroad even now. This problem has intensified with the blockade. That’s precisely why PROINPA focuses on producing seeds, although that is not our only line of work.

Gerardo (Lalo) Rivas Gil: Latin America, particularly the Andes range which we are now standing in, is the home of the potato. However, we got to a point where in Venezuela 99% of the seed potatoes were imported! For some four decades, Venezuela would buy most of its seed potatoes not only from Germany and Canada, but also from France and Holland. In fact, there were years when Venezuela paid as much as 400 million dollars to purchase seeds!

On top of that, the varieties we got were Royalty and Granola, which have their virtues, but are not always the most appropriate for our conditions.

When we conceived of PROINPA, we were lucky enough to get Chávez’s attention. He understood the strategic value of seeds, and we got government funding, which helped us a great deal. That’s when we began to study and develop science. But it wasn’t easy in those early days. Many said: “you are a bunch of campesinos, you can’t do this!” or “You can’t run these processes because you don’t have a PhD or aren’t linked to established labs.” Of course, “established labs” is a euphemism for corporate agribusiness.

By 2005, we were producing seed potatoes. And we’ve kept at it year after year, rain or shine. We’ve done so sometimes with significant support from public institutions, and sometimes with very little, but always with the interests of big business against us. The blockade, the pandemic, the capitalist enemies–none of that brought us to a halt, because we’re really stubborn!

Our commitment to developing (and caring for) good, sturdy, and healthy seed potatoes to feed the people of Venezuela has only grown over the years. We have a long way to go and I’m sure we will face many more hurdles, but we learn from every difficulty we face.

Rafael Romero: We are in Venezuela’s tropical Andes region. The ground and biological cycle here have their own characteristics. Conventional agriculture, which operates with a single model and responds to the interests of a few, does not necessarily work for us. In our region, one of the problems that we have faced over the years is that we get contaminated seeds from abroad. In other words, a seed that performs one way in Canada won’t necessarily perform the same way here because it can arrive contaminated.

When a seed potato comes with a virus, that doesn’t only mean that its performance will be sub-optimal, but it will also pollute the ground and generate dependency on chemical inputs. That’s why the scientific investigation that we are promoting here, from our CEBISA labs, is so important… I would dare to say that this is even more relevant now that the U.S. has built a wall around our country!

Venezuela could be self-reliant when it comes to potato production: there is plenty of optimal land and the campesinos are eager to produce. In fact, with some support and investment in technology, we could quickly become exporters. According to a study carried out by the Economic Potato Circuit, an initiative promoted by the Ministry of Communes, Venezuela has at least 50 thousand hectares suitable for growing potatoes, and PROINPA is already promoting potato farming in many states through an alliance with the Science and Technology Ministry.

Caroly Higuera: PROINPA is known for its innovations in the production of seed potato, but we do a lot more than that. At CEBISA we produce seeds for garlic, stevia, coffee, and other vegetables. PROINPA produces bio-inputs, promotes the conservation of water sources and the land with agroecological practices, and works on the genetic improvement of bovine and ovine cattle. Finally, we promote technical and scientific education among our associates and other producers, and we work on the social organization of production.

Right now, while improving seed potatoes in our lab and producing hundreds of thousands of seeds every year, we are additionally doing field research with carrot and cabbage seeds, among others. Additionally,: we’re working to develop a proposal for biological corridors in the Chama River Basin [the river that flows by Mucuchies] to reduce the impact of climate change. This project, like many others, is a collaboration with public institutions. In this case, we have access to satellite photos of the basin, which allows us to project future uses.

We also work with agroecology students from the Simón Rodríguez University to understand the effects of fertilizers on women’s health in the municipality. In fact, we have a number of research initiatives underway in collaboration with academic and research institutions.

Marisol Montilla: PROINPA is about perseverance and dedication, about loving the land that we stand on, and about looking for scientific solutions to the problems that rural producers face in these highlands.

The educational system, the media, and popular belief coalesce in a single discourse: seed production is something that can only be done by a few top scientists; you practically have to be a NASA researcher to succeed! However, our experience shows that the best way to improve and produce seeds is when social actors, researchers, campesinos, and institutions all come together. Without direct campesino participation, private interests take over.

Corporate interests behind conventional agriculture prescribe a method that doesn’t consider human realities or the ecosystem. In fact, as we say here at PROINPA, those who have control of the seed have the power. Why? Because they control the food cycle. We don’t want foreign corporations to control our food cycle. We are about empowering campesinos with the science and the seeds that they need so that our country can be sovereign.

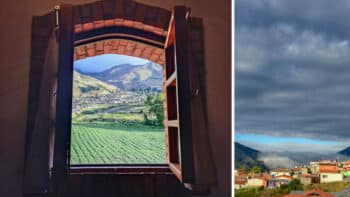

Landscapes around Mucuchies, Mérida, the PROINPA home base. (Voces Urgentes)

Fortunately, in Venezuela, we have the human, technical and scientific capacities to develop a model that suits our conditions. We also have the land, the water, and plenty of sunlight.

PROINPA’S PRINCIPLES

Rafael Romero: PROINPA promotes an integral approach to agriculture based on three principles. Our first principle is the diversification of campesino production units. We work to break with monoproduction, which is the conventional model. Monoproduction is a model that benefits big agribusiness and doesn’t meet the needs of the producer or the environment.

Diversifying production is key to promoting sustainable agriculture in both environmental and economic terms. Our aim is that every farm have at least five different crops and animal rearing activities combined. We also work to promote the recycling of nutrients to fertilize the ground. In short, we recreate the basic elements of traditional agriculture.

Our second principle is incorporating science and technology into the production process, which ensures that traditional agriculture methods offer good and sustainable yields.

Finally, our third principle is the social organization of production. By this we mean that producers organize democratically and cooperate to promote agroecology, displace the use and abuse of agro-chemicals, protect water sources and the ground, and preserve our cultural heritage.

PROINPA’s CEBISA facilites. (Voces Urgentes)

But these three principles could be summed up into one larger mission: to preserve small and mid-sized farming and campesino life in the long term.

PRODUCERS

Vladimir Balza: PROINPA is all about sovereignty. Top-notch pre-basic seed potatoes are produced at the CEBISA laboratories and greenhouses. As an associate producer, I get these seed potatoes at a reduced price. Using the pre-basic seeds, I multiply them to get a certified seed potato crop. A percentage of that crop goes back to PROINPA to scale up sovereign seed distribution. I then place some of the certified seeds in the market while another batch goes to production for consumption.

PROINPA is directly related to food sovereignty for two reasons. First, it breaks with the need to import seed potatoes. Second, imported seeds often come with diseases that hurt the land and force us into purchasing chemical inputs. Through PROINPA, we are breaking with that kind of dependency, although that doesn’t happen overnight.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that we are free from problems. The impact of the crisis and the blockade has been enormous and, more recently, another blight descended upon us: Colombian potatoes are flooding the market. That lowers the price of our main crop and makes it difficult for us to survive.

Julio Orlando Mora Parra: I’m not a direct PROINPA associate, but as a potato producer, I receive 2000 seed potatoes from PROINPA every year via our irrigation committee Future installments of this investigation will focus on the role and character of irrigation committees.* The agreement goes as follows: I multiply the seeds. Once the cycle closes I keep 70% of the production, while the remaining 30% goes to PROINPA so that they can redistribute to another irrigation committee.

Vladimir Balza: Not only does PROINPA deliver high-quality seed potatoes, but CEBISA’s lab also produces other seeds that campesinos like me have access to. There are workshops on alternative agriculture and an ongoing program to promote farm diversification as well.

José Gregorio Gil Pérez: I joined PROINPA more than ten years ago when seed imports from Canada, Holland, and Germany began to dwindle. In the beginning, I was a bit leery of PROINPA’s seed potatoes, because we’d been told that we aren’t capable of producing good seeds in Venezuela, that they have to come from foreign enterprises, and so on. However, our seeds have very good genetics.

Over the years, I have learned a lot about the process of multiplying the seed, and I feel that I’m not only producing for myself and my family; I’m also contributing to my country.

PROINPA’S EARLY DAYS

César Mesa: In the late 90s, the Belgian NGO Andes Tropicales had a project here in the highlands to improve animal rearing and promote organic food production. They also had other lines of work including ecotourism. Andes Tropicales was very important for many of us. When it came to an end, Rafael Romero became the engine behind what we now know as PROINPA.

In its early days, PROINPA brought together 25 producers, and we eventually became an association. Of course, when you begin something, it doesn’t satisfy your desires right away. However, since its beginnings, PROINPA became a model for participation: every associated producer has a say and a vote. In other words, decisions are not taken by a single person. That is good, and that is what has kept the organization going over the years.

Rafael Romero: PROINPA was born in 1999. However, 2002 was an important year for us. That is when we applied for support from the fledgling Science and Technology Ministry [MINCyT]. They had an initiative that was called “Clusters” that eventually came to be known as “Socialist Networks of Productive Innovation” [Redes Socialistas de Innovación Productiva].

When the Clusters got going, there were 643 projects nationwide, but ours was the only one working with seeds. The Cluster initiative was really great, although only about 30% of those projects survived over time. Perhaps that’s not surprising, since we are talking about scientific innovation.

The operational principle used in the Clusters project was that each initiative would work in cooperation with (and get support from) local and national institutions in the field. Our “cluster” included Mérida’s Foundation for the Development of Science and Technology [FUNDACITE], the National Institute of Agricultural Investigation [INIA], the local Mucuchies government, the Los Andes University Environmental Sciences Institute, the Training and Innovation Foundation for the Support of the Agrarian Revolution [CIARA], and the Cuba-Venezuela Agreement.

In 2003 Chávez himself handed a check over to us to buy a greenhouse and equipment to sterilize the ground [needed for seed-production]. Unfortunately, we were not able to get the project going until 2005 because the INIA didn’t have the seedlings that we needed to get the project moving. The INIA was likewise expected to facilitate lab testing and offer technical support, but they were frankly remiss in this process.

PROINPA associates meet on the 21st of every month. (Voces Urgentes)

In the end, by 2005, we were able to begin producing seeds and, with support from several of the institutions that I mentioned before, seed production took off with full force.

THE ORGANIZATION

Gerardo (Lalo) Rivas Gil: Perhaps more important than the production of seeds is the organizational model that PROINPA promotes. Here we take all important decisions collectively, in an assembly that is held on the 21st of every month, be it Tuesday or Sunday. We are a horizontal organization. Formally, at the top of the structure is the Technical Coordinator. That’s my role at the moment, but I can’t make any important decisions on my own, so the role is mostly symbolic.

Needless to say, this structure has nothing to do with capitalist organization, and I believe it could be the organizational model for the future socialist society that we dream of.

Rafael Romero: PROINPA is run by and for the producers. I’m one of 85 associates, and my vote counts the same as anybody else’s. Of the 85 associated producers, 10 of us work at the CEBISA labs. Furthermore, every employee has the same rights as an associate producer. There are no bosses at PROINPA.

However, our internal structure doesn’t close us in on ourselves: we often get support and technical assistance from many institutions and sister organizations. Assistance and advice are always welcome, but at the end of the day, it is the associated producers who decide PROINPA’s course of action.

This democratic model goes back to 1999, when the PROINPA came into existence. In legal terms, we wanted the organization to be a cooperative but the laws of the time were very restrictive, so we finally established ourselves as an association. However, we operate in ways very different from a conventional association, so our legal structure doesn’t exactly match our assembly-based modus operandi.

Now, the fact that PROINPA is a democratic organization doesn’t mean that everyone does the same thing at the same time. We have six technical branches – administration, commercialization, environment, auditing, and so on–and each PROINPA member belongs to one of them. In turn, each branch has a spokesperson, and they are the ones who bring proposals to the assembly, which is our executive body.

I should highlight, however, that our organization is agile. A body that is called “General Coordination” has leverage to make some decisions on the spot when needed. This includes purchasing inputs in an emergency, enabling conversations that may lead to agreements with institutions or organizations, and approving certain banking transactions. All of these processes will be reviewed in our monthly assembly, so nothing happens behind closed doors!

Richard Rivas: We meet on the 21st of every month, and that’s one of the most wonderful things about PROINPA. The day begins early, peeling potatoes for a big sancocho [stew]. We then gather in the assembly and plan, confer, and debate.

We also get a detailed monthly report from different PROINPA branches. When that is done, we move on to our hearty sancocho, we update each other on our families’ health and the whereabouts of our children, and we share our notes on production.

FOOTNOTES

* Pre-basic seeds represent the first stage in seed production. They are also called breeder seeds, and are produced under the highest level of genetic control to ensure seeds that are genetically pure, accurately represent the variety, and are disease-free. Basic seeds, in turn, are produced from pre-basic seeds, maintaining their genetic purity. They are later used as the source for registered and then certified seeds, which are employed in commercial crop production.

PROINPA usually offers pre-basic seeds to producers with the expectation that they will “multiply” them to produce basic, then registered, and eventually certified seeds. This increases the quantity of seeds geometrically.

** Future installments of this investigation will focus on the role and character of irrigation committees.