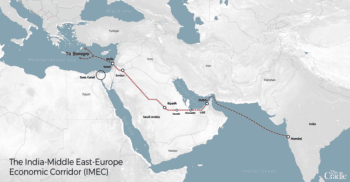

The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) is a massive public diplomacy op launched at the recent G20 summit in New Delhi, complete with a memorandum of understanding signed on 9 September.

Players include the U.S., India, UAE, Saudi Arabia, and the EU, with a special role for the latter’s top three powers Germany, France, and Italy. It’s a multimodal railway project, coupled with trans-shipments and with ancillary digital and electricity roads extending to Jordan and Israel.

If this walks and talks like the collective west’s very late response to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched 10 years ago and celebrating a Belt and Road Forum in Beijing next month, that’s because it is. And yes, it is, above all, yet another American project to bypass China, to be claimed for crude electoral purposes as a meager foreign policy “success.”

No one among the Global Majority remembers that the Americans came up with their own Silk Road plan way back in 2010. The concept came from the State Department’s Kurt Campbell and was sold by then-Secretary Hillary Clinton as her idea. History is implacable, it came down to nought.

And no one among the Global Majority remembers the New Silk Road plan peddled by Poland, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, and Georgia in the early 2010s, complete with four troublesome trans-shipments in the Black Sea and the Caspian. History is implacable, this too came down to nought.

In fact, very few among the Global Majority remember the $40 trillion U.S.-sponsored Build Back Better World (BBBW, or B3W) global plan rolled out with great fanfare just two summers ago, focusing on “climate, health and health security, digital technology, and gender equity and equality.”

A year later, at a G7 meeting, B3W had already shrunk to a $600 billion infrastructure-and-investment project. Of course, nothing was built. History really is implacable, it came down to nought.

Map of The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC)

The same fate awaits IMEC, for a number of very specific reasons.

Pivoting to a black void

The whole IMEC rationale rests on what writer and former Ambassador M.K. Bhadrakumar deliciously described as “conjuring up the Abraham Accords by the incantation of a Saudi-Israeli tango.”

This tango is Dead On Arrival; even the ghost of Piazzolla can’t revive it. For starters, one of the principals—Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman—has made it clear that Riyadh’s priorities are a new, energized Chinese-brokered relationship with Iran), with Turkiye, and with Syria after its return to the Arab League.

Moreover, both Riyadh and its Emirati IMEC partner share immense trade, commerce, and energy interests with China, so they’re not going to do anything to upset Beijing.

At face value, IMEC proposes a joint drive by G7 and BRICS 11 nations. That’s the western method of seducing eternally-hedging India under Modi and U.S.-allied Saudi Arabia and the UAE to its agenda.

Its real intention, however, is not only to undermine BRI, but also the International North-South Transportation Corridor (INTSC), in which India is a major player alongside Russia and Iran.

The game is quite crude and really quite obvious: a transportation corridor conceived to bypass the top three vectors of real Eurasia integration—and BRICS members China, Russia, and Iran—by dangling an enticing Divide and Rule carrot that promises Things That Cannot Be Delivered.

The American neoliberal obsession at this stage of the New Great Game is, as always, all about Israel. Their goal is to make Haifa port viable and turn it into a key transportation hub between West Asia and Europe. Everything else is subordinated to this Israeli imperative.

IMEC, in principle, will transit across West Asia to link India to Eastern and Western Europe—selling the fiction that India is a Global Pivot state and a Convergence of Civilizations.

Nonsense. While India’s great dream is to become a pivot state, its best shot would be via the already up-and-running INTSC, which could open markets to New Delhi from Central Asia to the Caucasus. Otherwise, as a Global Pivot state, Russia is way ahead of India diplomatically, and China is way ahead in trade and connectivity.

Comparisons between IMEC and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) are futile. IMEC is a joke compared to this BRI flagship project: the $57.7 billion plan to build a railway over 3,000 km long linking Kashgar in Xinjiang to Gwadar in the Arabian Sea, which will connect to other overland BRI corridors heading toward Iran and Turkiye.

This is a matter of national security for China. So bets can be made that the leadership in Beijing will have some discreet and serious conversations with the current fifth-columnists in power in Islamabad, before or during the Belt and Road Forum, to remind them of the relevant geostrategic, geoeconomic, and investment Facts.

So, what’s left for Indian trade in all of this? Not much. They already use the Suez Canal, a direct, tested route. There’s no incentive to even start contemplating being stuck in black voids across the vast desert expanses surrounding the Persian Gulf.

One glaring problem, for example, is that almost 1,100 km of tracks are “missing” from the railway from Fujairah in the UAE to Haifa, 745 km “missing” from Jebel Ali in Dubai to Haifa, and 630 km “missing” from the railway from Abu Dhabi to Haifa.

When all the missing links are added up, there’s over 3,000 km of railway still to be built. The Chinese, of course, can do this for breakfast and on a dime, but they are not part of this game. And there’s no evidence the IMEC gang plans to invite them.

All eyes on Syunik

In the War of Transportation Corridors charted in detail for The Cradle in June 2022, it becomes clear that intentions rarely meet reality. These grand projects are all about logistics, logistics, logistics—of course, intertwined with the three other key pillars: energy and energy resources, labor and manufacturing, and market/trade rules.

Let’s examine a Central Asian example. Russia and three Central Asian “stans”—Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan—are launching a multimodal Southern Transportation Corridor which will bypass Kazakhstan.

Why? After all, Kazakhstan, alongside Russia, is a key member of both the Eurasia Economic Union (EAEU) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).

The reason is because this new corridor solves two key problems for Russia that arose with the west’s sanctions hysteria. It bypasses the Kazakh border, where everything going to Russia is scrutinized in excruciating detail. And a significant part of the cargo may now be transferred to the Russian port of Astrakhan in the Caspian.

So Astana, which under western pressure has played a risky hedging game on Russia, may end up losing the status of a full-fledged transport hub in Central Asia and the Caspian Sea region. Kazakhstan is also part of BRI; the Chinese are already very much interested in the potential of this new corridor.

In the Caucasus, the story is even more complex, and once again, it’s all about Divide and Rule.

Two months ago, Russia, Iran, and Azerbaijan committed to building a single railway from Iran and its ports in the Persian Gulf through Azerbaijan, to be linked to the Russian-Eastern Europe railway system.

This is a railway project on the scale of the Trans-Siberian—to connect Eastern Europe with Eastern Africa and South Asia, bypassing the Suez Canal and European ports. The INSTC on steroids, in fact.

Guess what happened next? A provocation in Nagorno-Karabakh, with the deadly potential of involving not only Armenia and Azerbaijan but also Iran and Turkiye.

Tehran has been crystal clear on its red lines: it will never allow a defeat of Armenia, with direct participation from Turkiye, which fully supports Azerbaijan.

Add to the incendiary mix are joint military exercises with the U.S. in Armenia—which happens to be a member of the Russian-led CSTO—cast, for public consumption, as one of those seemingly innocent “partnership” NATO programs.

This all spells out an IMEC subplot bound to undermine INTSC. Both Russia and Iran are fully aware of the former’s endemic weaknesses: political trouble between several participants, those “missing links” of track, and all important infrastructure still to be built.

Turkish Sultan Recep Tayyip Erdogan, for his part, will never give up the Zangezur corridor across Syunik, the south Armenian province, which was envisaged by the 2020 armistice, linking Azerbaijan to Turkiye via the Azeri enclave of Nakhitchevan—that will run through Armenian territory.

Baku did threaten to attack southern Armenia if the Zangezur corridor was not facilitated by Yerevan. So Syunik is the next big unresolved deal in this riddle. Tehran, it must be noted, will go no holds barred to prevent a Turkish-Israeli-NATO corridor cutting Iran off from Armenia, Georgia, the Black Sea, and Russia. That would be the reality if this NATO-tinted coalition grabs Syunik.

Today, Erdogan and Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev meet in the Nakhchivan enclave between Turkiye, Armenia, and Iran to start a gas pipeline and open a military production complex.

The Sultan knows that Zangezur may finally allow Turkiye to be linked to China via a corridor that will transit the Turkic world, in Azerbaijan and the Caspian. This would also allow the collective west to go even bolder on Divide and Rule against Russia and Iran.

Is the IMEC another far-fetched western fantasy? The place to watch is Syunik.