The village of Gavidia lies some 3700 meters above sea level in Mérida state. There, a handful of local producers have come together in the Native Potato Project, breaking with conventional agriculture’s tendency toward monoculture and monopolistic control of seeds. The project is about the preservation of some fifteen varieties of native potatoes and two species, but more than that, Gavidia’s Native Potato Project is about safeguarding a way of life that rejects the dictates of capitalist and colonial modernity.

Gavidia’s Native Potato Project

María Cantalicia Torres is a producer and communal teacher in Gavidia | Bernabé Torres is a stonemason, a wood artisan, and a producer in Gavidia | Liccia Romero is a university professor and a participant in Gavidia’s Native Potato Project. (Voces Urgentes)

Liccia Romero: The Gavidia glacial valley is home to two micro-watersheds: Carache and Las Piñeras. The goal of the Native Potato Project here is to create a collaborative space where local campesinos can work together with a vision not permeated by the dictates of capitalist modernity.

The objective of the project is to care for and produce native potatoes using a farming technique known as fallowing in a way that is specifically adapted to the unique ecosystem of this glacial valley. This sustainable approach stands in stark contrast to intensive agriculture, ensuring the preservation of the delicate highland ecosystem and the rich cultures intertwined in it.

Bernabé Torres: For me, our project is not about the recovery of the native potato, because the native potato has always been part of my life. When I was a child, I ate these potatoes, and now, as an adult, I also care for them and grow them.

Here, in this plot of land, we grow many varieties, including Guadalupe, Rosada, Rolona, Reinosa, Criolla, Arepita, and Ojos Carites.

Some ask me: why do you grow native potatoes? They wonder if it is some sort of attachment to old traditions. To that, I say, no, we grow these potatoes because they are sturdy, they do well in our harsh climate, they are more resistant to pests, and they don’t need agrochemicals.

María Cantalicia Torres: Native potatoes grow more slowly than conventional ones, but they last much longer. They are also tastier and richer in nutrients that concentrate on their intense colors and in the skin, which we always eat. That’s because our varieties haven’t gone through so many modifications and interventions, and they are free of chemicals.

In this valley, we live long lives because we are less exposed to toxic inputs and because the base of our diet, the native potato, has many nutritional properties.

Conventional seed potatoes come diseased: they carry pests and they require many toxic inputs. We are rescuing what is good, what is healthy, what is resilient, and what is natural. We are rescuers of life: of the wonderful biological diversity that our valley gave us and the culture that has grown alongside it.

Liccia Romero: I wasn’t born here, but I fell in love with Gavidia as soon as I set foot in the valley.

I came here when I was studying agroecology, and my objective was to find the origin of the Venezuelan potato, which has been displaced by conventional, non-native potatoes.

Whereas Canadian potatoes are about 100 years old and their origin is in the Andes, our native potatoes date from long before the colonial occupation. This means that there was an originary potato that has been genetically eroded over the centuries. At least, that was my hypothesis when I came here.

But when I arrived, I found that the people had another vision, which isn’t based on the idea of genetic erosion. They argue that there was a sort of act of retraction in the face of the aggression of modernity that was eroding the endogenous potato. They contend that that’s how Gavidia became a territory of resistance, and that’s why the ancestral knowledge surrounding the potato still exists here.

The Native Potato Project is especially significant, because its production entails an entire, integral, holistic way of life. This means coexisting with the land and the ecosystem: production must happen without causing harm. Hence, the emphasis on sustainable agriculture and the rejection of intensive farming practices that harm the ground, the ecosystem as a whole, and the culture surrounding it.

María Cantalicia Torres: The native potato is stigmatized. People often call it papa de año because they assume that its production cycle takes a whole year. That’s not the case: the cycle here in Gavidia is six to nine months, but the cycle of the conventional potato is also longer here, because we are more than 3000 meters above sea level.

The term papa de año actually has its roots in the long storage life of the native potato, which can be kept for a year and even longer if dehydrated. This is important because it’s an added perk in terms of food sovereignty: we have the seeds, we care for the seeds, and we can store the crop for a long time.

Liccia Romero: The worldview of the native potato producers revolves around the preservation of their family traditions, their roots, and the life that surrounds them. However, this doesn’t mean that they are closed in on themselves. Their vision is about valuing what comes from here and their rich inheritance, while remaining open to the world.

Fundamentals of the project

Left: native potatoes from Gavidia. Right: Gavidia landscape. (Voces Urgentes)

Liccia Romero: Gavidia’s Native Potato Project is based on three key components. First, there’s the “Learning Community” [Comunidades de Aprendizaje], which is run in cooperation with the Open Studies Program of Simón Rodríguez National University.

The Open Studies Program allows for the students of an organized community to define their own curriculum in a conversation with a tutor. In the program, the diploma is not the end-all and be-all. At the core of this approach here are what we call the maestros pueblo. They are individuals who organize knowledge surrounding native potatoes and share it with the community.

The second component focuses on production, and involves the reproduction of native seed potatoes for consumption and reintroduction into the food system.

Finally, the third component is research. Research helps us to recover endogenous knowledge, which is systematized and compared with scientific knowledge to identify similarities and contradictions. Ultimately, our goal is to incorporate the components of marginalized campesino knowledge systems into the curricula, even if it doesn’t strictly align with so-called scientific knowledge and even if it sometimes contradicts the conventional scientific approach.

Teaching and learning

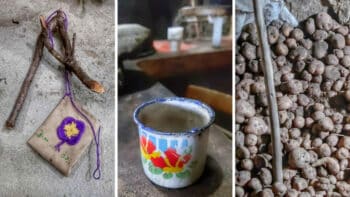

The potato flower (left), is the symbol for Gavidia’s Native Potato Project. (Voces Urgentes)

María Cantalicia Torres: I worked teaching the kids of Gavidia for many years, because there was no active school here. I committed myself to teaching because, although we live in a beautiful valley with much to preserve, our children must learn about the world. I called my initiative “New Readers Circle,” and I ran it out of my living room.

My teaching went hand in hand with the recovery of the native potato that my partner and I have been promoting. Eventually, when Gavidia’s Native Potato Project got off the ground, my experience as a teacher morphed into sharing our knowledge and our love for the native potato with the community and with visitors.

But teaching must go hand in hand with learning. For that reason, I began to work with other women some time ago on recovering traditional weaving practices, both on the loom and freehand. That was a project promoted by PROINPA, and out of it came a community of women weavers that continues producing and teaching.

Liccia Romero: What we call Learning Communities are spaces that promote the social practice of generating new knowledge, with students systematizing and socializing knowledge within their community. These are not efforts based on the extraction of knowledge. It’s not about a scientist landing in the territory to interview the people, and later claiming that theirs was a “participative investigation” when they present it to their colleagues in academia because… they talked to the people!

Learning Communities is an instrument that promotes the production of knowledge in a rich and organized dynamic of exchange. The focus is working with young people in a space sanctioned by academia. Turning the tables this way is important because academic spaces are generally arrogant and undervalue people’s knowledge.

Campesinos are often excluded from formal education processes, and even more so when it comes to producers in remote Andean valleys. Learning Communities are not there as some kind of bandaid. Learning Communities do what families and communities of producers did in the past: they teach how to care for the highlands and share campesino agriculture practices; they learn about the different native potato varieties and their virtues; they also learn about medicinal plants and natural cures, and about the preservation of culture, music, and tales.

However, our educational project is not limited to the Learning Communities. We promote the yearly Native Potato Eco-festival, which is also a tool for the production and socialization of knowledge. The festival allows producers, scientists, and fellow travelers to exchange knowledge.

The Eco-festival happens once a year in December. For three days, people from the region–and sometimes further–meet for educational workshops, organize plays and poetry readings, walk the valley, taste the local potato-based cuisine, and take turns singing the songs of their parents and grandparents.

Practices of healing

In Gavidia, teaching and culture go hand in hand. (Voces Urgentes)

Liccia Romero: Technology and science require the native potato and not the other way around. That’s why we say that Gavidia’s Native Potato Project came to heal a problem that was brought about by modernity.

As Bernabé [Torres] often reminds us, we lost both valuable knowledge and native potato varieties when conventional potato seeds were introduced into the valley. Conventional potatoes and the toxic inputs that go with them entered the region violently. With them came pests and diseases that hurt the soil and the ecosystem.

That’s why we built a greenhouse: the aim is to isolate native potatoes and recover them. Ultimately, we work to propagate them in controlled exterior spaces.

Bernabé Torres: With the conventional potato came the tractor, which does not feel for the life of the soil and hurts our ecosystem by removing the top layer of soil, which is the richest. Instead, we plow with oxen. Oxen don’t damage the crop or the soil. When they are plowing, you can see them dance to avoid stepping on the plants.

We talk to the oxen as if they were one of us and they understand our voices.

PRESERVING ANCESTRAL KNOWLEDGE

In the Torres family greenhouse, they recover native seed potatoes and grow strawberries and flowers. (Voces Urgentes)

Liccia Romero: Campesino seeds are not recognized by modernity’s food systems, and thus monopolistic agro-corporations don’t consider them seeds but simply resources to exploit.

In essence, the seeds that have fed people in the Andes since time immemorial and reached Europe hundreds of years ago are viewed by corporations as merely phytogenetic resources. They see them as a genetic pool to be manipulated and turned into economic profit for a few.

That’s why the 2015 Seed Law in Venezuela has two certification systems: the Conventional Certification System and the Participatory Campesino Guarantee System [Sistemas de Garantía Participativa Campesina]. The Campesino System emerges from a movement that originated here in Gavidia; we were able to show that campesino practices not only do not harm the potato crops, but are efficient, despite departing from conventional methods. They also don’t harm the ecosystem.

Our struggle isn’t just over a narrative. We also crunched the numbers—which is something the academia appreciates—and found that in good conditions, on soil that has been fallow, and with organic fertilizers, a Rosada crop [a native potato variety] can yield 50 tons per hectare! That’s why Bernabé [Torres] says that there is no need to submit ourselves to Canadian multinational corporations. Native potatoes are good, healthy, and robust… and they are ours!

But what is ours must be protected. That’s why we work for political recognition. In 2015, the Ministry of Culture’s Cultural Heritage Institute declared the knowledge and traditions surrounding the native potato to be an “immaterial cultural good” that must be protected.

While this declaration focuses on the culture surrounding the native potato and not the plant itself, its important because it protects the social ecosystem for native potatoes.

Food sovereignty

Landscapes where the native potato grows. (Voces Urgentes)

Bernabé Torres: The corporations took our potatoes and came back to sell us conventional potatoes, which may be larger and more regular, but have lost many of the nutritional qualities of potatoes they descend from. However, in the course of expropriating our potatoes, they didn’t just take the species, they also took away a piece of our sovereignty.

That’s why among my parents and my grandparents, my partner and our children, we are all guardians of a common good that doesn’t belong to us but to the Venezuelan Andes as a whole: to its people.

María Cantalicia Torres: The sanctions have left many people without food and medicines, but that didn’t happen to us in Gavidia. We preserve the practices of our grandparents, who knew how to grow native potato crops and passed on to us their knowledge about the nutritional quality of each potato variety. They also passed on to our knowledge about the healing properties of the herbs in Gavidia. So, not only did we not go hungry here, but we also ate well and stayed healthy.

Liccia Romero: Sovereignty is not something that is merely symbolic. It is not just about drawing a line on a map or having a flag. Sovereignty should be understood as a comprehensive project.

The sovereignty of a territory has a great deal to do with knowing the ground on which we stand, the plants that grow on it, and the creatures that make this place their home. But sovereignty is also about the culture of the people who produce and live in a territory.

The native potato evolved in a tropical mountain climate and in synergy with this land and its people. If the native potato were to disappear, a culture and a whole way of living would vanish with it.

The native potato belongs to the people, not the corporations. To grow it, all the campesino needs is the seed. The native potato seed represents a break with dependency. It is sovereign.

The most important thing about the native potato—and when I talk about the native potato, I’m talking about campesino agriculture by extension—is that it preserves a system that is strategic and sovereign: a system based on sharing and living together. Everything else is technology at the service of a few.