SPECIES AT RISK

Endangered Wildlife of the Colorado River

Endangered Wildlife of the Colorado River

With the Earth already facing a human-caused sixth mass extinction, animal and plant ecosystems require as much assistance as they can get. Instead, humanity’s refusal to act in both their and our best interests for survival has put numerous additional species at risk. As the Colorado River continues to dry up, so do these species’ chances of surviving ongoing climate change.

WESTERN BURROWING OWLS

Western Burrowing Owls are permanent residents of the Southwestern U.S., but their numbers are dwindling. The owls are labeled vulnerable or imperiled in nearly every state within their territory. Severe drought and climate change may already be driving this decline, with future projections for the area only growing hotter. As the Colorado River shrinks and water use is cut back, burrowing owls struggle to survive in a rapidly changing landscape. Ironically, efforts to conserve water are making less water available to the owls, who had adapted to the man-made farms and irrigation systems. Moving forward, the species needs more attention and protection as it adapts to climate change.

SAGUARO CACTUS

The iconic Saguaro Cacti are struggling to survive Arizona’s droughts, with many dropping arms or toppling over altogether. Though the species is not yet endangered, Saguaros are increasingly threatened by a seemingly benign source: cattle feed grass. Apart from guzzling up the Colorado River’s water, the introduction of these exotic grasses to the desert has created the perfect environment for fire to spread, a threat the Saguaro Cacti are unadapted to. Should their populations drop off, entire ecosystems will be threatened by the loss of this keystone species, and countless birds, insects, and bats will lose a vital food and shelter source.

LESSER LONG-NOSED BAT

Lesser Long-Nosed Bats inhabit the Southwestern U.S. and Mexico, feeding off the nectar of flowering plants like agave and Saguaro Cacti. In fact, pollination by these little creatures supports tequila production across Mexico. But the bats, and the tequila byproducts alongside them, are facing serious threats from climate change and habitat loss. One study found that even under optimistic conditions, 59 percent of the bat’s habitat will be unsuitable for habitation by 2050. As temperatures rise and precipitation declines, the plants the bats depend on may shift their habitats or fail to flower. This includes Saguaro Cacti, which long-nosed bats depend on for night-blooming flowers.

BONYTAIL CHUB

Bonytail Chub are the rarest of the Colorado River’s endemic fish, evolving 5 million years ago. Their populations remain critically low even as other species begin the road to recovery; so low in fact, that the species is ‘functionally extinct,’ or unable to self-sustain their populations in the wild. Bonytails once swam along the entire expanse of the Colorado River, but now, due to man-made disruptions and draining of the river, this has shrunk dramatically. But even these populations could not survive without hatcheries to raise and release the fish annually. The ever-present threat of environmental pollutants, like spills or leaching of chemicals, still poses serious risk to bonytails, as does alteration of habitat. Recovering the Colorado River is a matter of life or full extinction for these fish.

RAZORBACK SUCKER

Razorback Suckers are endemic only to the Colorado River, over 3 million years old, and known to some as the “dinosaurs of the Colorado.” Classified as endangered since the 1990s, their populations are in decline throughout the Colorado River, with the Lower Basin seeing populations plummet over the last two decades. Human diversions of the river disturbed their natural habitats and processes, and the species has never recovered. Even now, Razorbacks’ critical habitats and hatcheries along the main Colorado River tributary, the Green River, face contamination from oil and gas companies eager to drill despite the risk to the fish. Their populations are only just beginning to be seen in the wild, but their recovery is still dependent on hatchery support and a clean, flowing river.

Part 7 Conclusion and Recommendations

We cannot save the Colorado River without combating corporate power

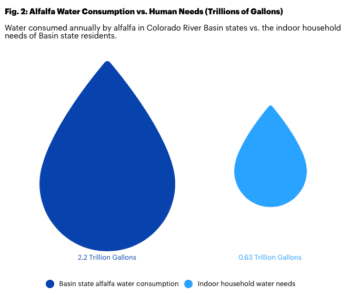

The Colorado River is deeply in crisis, and the solutions are already known. The arid U.S. West cannot sustain the factory farm system as water shortages continue. States must immediately de-prioritize wasteful industries such as large-scale alfalfa, nut trees, and mega-dairies. Each of these only contributes to worsening drought and climate change along the river, and continuing along this path only leads to harming communities and ecosystems that are struggling to survive in a hotter climate.

As Basin states and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation consider how best to move forward with allocations beyond 2026, state leaders must take this opportunity to radically rethink how water is used going forward in their states. Without drastic changes, there will not be enough water to sustain our future.

Food & Water Watch recommends:

At the federal level

- Pass the Farm System Reform Act (FSRA), which would put a moratorium on new and expanding factory farms and help transition dairy farmers away from factory farms. Pass a Farm Bill that incorporates the FSRA.

- Restrict federal conservation dollars from being used to prop up factory farms and alfalfa acreage.

- Restrict exports of alfalfa.

At the state level

- Ban new mega-dairies and the expansion of existing ones.

- Stop new and expanding large-scale tree nut and alfalfa acreage.

- Help transition small and medium-sized growers to more geographically appropriate and resilient crops.

- Improve water management practices by defining all water as a public trust resource, not a commodity subject to resource extraction at the expense of the public.

Tell authorities to take these steps and protect the Colorado River!

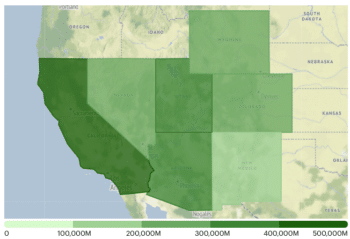

Crop calculations

We used an estimate of total water withdrawn and consumed by alfalfa in 17 Western states by Richter (2020),which relied on the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) 2012 Cropland Data Layer and compared this to 2012 USDA Census of Agriculture data on total tonnage of irrigated alfalfa produced across the same states. (“Consumed” means water diverted for irrigation that is removed from the immediate environment through evaporation, transpiration, or incorporation by crops. It is less than the total water “withdrawn” and applied to cropland, a portion of which returns to ground or surface-water sources and is therefore available for future use.)

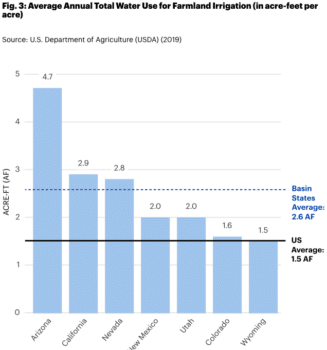

This amounted to an average of 6.5 inches of consumptive water per ton of irrigated alfalfa produced (or 2.4 acre-feet per acre harvested), which is relatively in line with consumptive estimates in Basin states from various sources, although likely below usage in regions of California that harvest alfalfa up to 10 times a year. It is also lower than estimates in recent Food & Water Watch reports featuring California and New Mexico, which instead used regional estimates of total irrigation water withdrawn and applied.

We applied the 6.5 inches figure to 2022 USDA Agricultural Survey data on alfalfa production in each Basin state. Since Survey data do not report alfalfa harvests by irrigation status, we estimated the percent of alfalfa acreage irrigated in each Basin state in 2017 (the latest Agricultural Census year) and adjusted the 2022 survey data to reflect these estimates. Similarly, we estimated water use by large alfalfa farms (harvesting 1,000-plus acres) using 2017 Census data.

Pecan water use estimates for New Mexico and Arizona come from Griego (2022), whose literature review found that the amount of water diverted for irrigating pecan trees in the U.S. Southwest ranged from 4.3 to 8.2 acre-feet per acre per year. We used the midpoint of 6.25 acre-feet per acre annually and applied it to USDA Survey data on pecan-bearing acres in both states. Almond and pistachio water use estimates for California come from a Congressional Research Service report citing data from the University of California at Davis, which estimates 3.5 acre-feet per acre per year of applied irrigation water. We similarly applied this figure to USDA Survey data to estimate the increase in water diverted to expanding nut crop production in California.

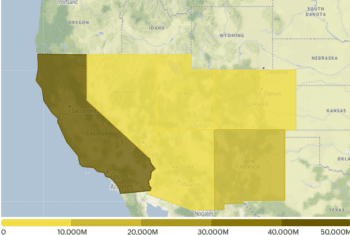

Dairy calculations

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s definition of a medium dairy concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO) includes those that confine 200-699 cows for at least 45 days per year, on operations that lack cropland or pasture and discharge waste into surface waters. In the present report, mega-dairies refer to operations with 500 or more cows, as this corresponds with data categories in the 2017 USDA Census of Agriculture, which do not provide information on confinement and waste management.

We pulled USDA Agricultural Census and Survey data to estimate the total milk produced on operations with 500 or more head of dairy cows within each Basin state. We applied these figures to an equation from Mekonnen et al. (2012), which estimated the total lifecycle water use needed to produce feed, water cows, and clean buildings at industrial-scale dairy operations in the U.S. (it does not include water used to flush manure into storage systems). Since this report also focuses heavily on water consumed by alfalfa (a major livestock feed), we focused on the water simply needed to water the cows and wash facilities, which Mekonnen et al. estimate at 1.9 percent of the total lifecycle use.

Water use comparisons

We used the State of California’s target of 42 gallons per person per day as our basis for residential indoor water needs. We pulled population and land area data on Basin states and cities (not the greater metropolitan areas) as well as average persons per household, from the U.S. Census Bureau’s QuickFacts.

Notes:

National Integrated Drought Information System, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “Special Edition Drought Status Update for the Western United States.” January 24, 2023; Griffin, Melissa et al. “Drought monitor spells good news for California, but ‘not out of the woods’ on megadrought.” ABC News. March 2, 2023.Robison, Jason et al. “Challenge and response in the Colorado River Basin.” Water Policy. Vol. 16, Iss. 12. March 2014 at 12 to 13.Ibid. at 16 to 17.U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Department of the Interior (DOI). “Colorado River Basin Ten Tribes Partnership Tribal Water Study.” December 2018 at i; Partlow, Joshua. “Officials fear ‘complete doomsday scenario’ for drought-stricken Colorado River.” Washington Post. December 1, 2022.Robison et al. (2014) at 20; Bureau of Reclamation (2018) at i.Robison et al. (2014) at 17 and 20.Falconer, Rebecca. “Drought-hit Colorado River water supplies near ‘moment of reckoning.’” Axios. June 15, 2022; Bolinger, Becky. “Depleted by drought, Lakes Powell and Mead were doomed from the beginning.” Washington Post. September 10, 2021.Stern, Charles V. et al. Congressional Research Service (CRS). “Management of the Colorado River: Water Allocations, Drought, and the Federal Role.” R45546. May 5, 2023 at 9.Falconer (2022).Robison et al. (2014) at 24; Fleck, John and Anne Castle. “Green light for adaptive policies on the Colorado River.” Water. Vol. 14, Iss. 2. 2022 at 2; Stern (2023) at 17.Fleck and Castle (2022) at 2.Milly, P.C.D. and K.A. Dunne. “Colorado River flow dwindles as warming-driven loss of reflective snow energizes evaporation.” Science. Vol. 367, Iss. 6483. February 20, 2020 at abstract; James, Ian. The Republic. “About 40 million people get water from the Colorado River. Studies show it’s drying up.” USA Today. February 22, 2020.Fountain, Henry. “Colorado River reservoirs are so low, government will delay releases.” New York Times. May 3, 2022; Yachnin, Jennifer. “Could a river finally run through the Glen Canyon Dam?” E&E News. January 27, 2023; U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. DOI. Water Operations: Historic Data. Available at . Accessed June 2023.Dance, Scott. “Lake Powell is rising more than a foot a day. But megadrought’s effects will still be felt.” Washington Post. May 11, 2023.Robison et al. (2014) at 23; Gardner, Jeff. “Deception and science in the Colorado River.” Desert Times. January 1, 2020; Fleck and Castle (2022) at 2.Sakas, Michael Elizabeth. “If the Colorado River keeps drying up, a century-old agreement to share the water could be threatened. No one is sure what happens next.” Colorado Public Radio. November 19, 2021.U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Letter to Paul Davidson. Chief, Water Management Group Water and Power Division. “Operation Plan for Colorado River Reservoirs.” August 21, 2021 at 1 to 2.Sabo, John. “Are markets a wet dream for U.S. Western water?” Forbes. February 10, 2022.Ronayne, Kathleen and Suman Naishadham. “California releases its own plan for Colorado River cuts.” Associated Press. January 31, 2023.Sakas, Michael Elizabeth. “Colorado River states need to drastically cut down their water usage ASAP, or the federal government will step in.” Colorado Public Radio. June 17, 2022.Flavelle, Christopher. “A breakthrough deal to keep the Colorado River from going dry, for now.” New York Times. Updated May 25, 2023.Jones, Benji. “Why the new Colorado River agreement is a big deal–even if you don’t live out West.” Vox. May 23, 2023.“Consumed” means water diverted for irrigation that is removed from the immediate environment through evaporation, transpiration, or incorporation by crops. It is less than the total water “withdrawn” and applied to cropland, a portion of which returns to ground- or surface-water sources and is therefore available for future use. See U.S. Department of the Interior. U.S. Geological Survey. “Estimated Use of Water in the United States in 2015.” Circular 1441. 2018 at Glossary and 59 to 61.Richter, Brian et al. “Water scarcity and fish imperilment driven by beef production.” Nature Sustainability. Vol. 3. April 2020 at 320 and 321, Table 1.U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. DOI. “Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study.” December 2012 at 3.The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s definition of a medium dairy concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO) includes those that confine 200-699 cows for at least 45 days per year, on operations that lack cropland or pasture and discharge waste into surface waters (see 40 CFR § 122.23). In this piece, mega-dairies refer to operations with 500 or more cows, as this corresponds with data categories in the 2017 U.S. Department of Agriculture Census of Agriculture, which do not provide information on confinement and waste management.Richter et al. (2020) at 320.U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). “2018 Irrigation and Water Management Survey.” Volume 3, Special Studies, Part 1. AC-17-SS-1. November 2019 at 14.MacDonald, James M. et al. USDA. Economic Research Service (ERS). “Consolidation in U.S. Dairy Farming.” Economic Research Report No. 274. July 2020 at 11; Liebrand, Carolyn. USDA. Rural Business-Cooperative Service. “Structural Change in the Dairy Cooperative Sector, 1992-2000.” RBS Research Report 187. October 2001 at iii, 1, 3, and 11.Lee, Seth. IBISWorld. “Dairy Farms in the U.S.” Industry Report 11212. July 2022 at 4, 7, and 17.See Food & Water Watch (FWW). “The Economic Cost of Food Monopolies: The Dirty Dairy Racket.” January 2023.Blayney, Don and Mary Anne Normile. USDA. ERS. “Economic Effects of U.S. Dairy Policy and Alternative Approaches to Milk Pricing: Report to Congress.” Administration Publication No. 076. July 2004 at 3 to 5, 13, and 27 to 29; Hanawa Peterson, Hikaru. Kansas State University. “Geographic Changes in U.S. Dairy Production.” Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Agricultural Economics Association. Long Beach, California. July 28-31, 2002 at 1 to 4; MacDonald et al. (2020) at 1, 5 to 7, and 18.FWW analysis of USDA. NASS. 2017 Census of Agriculture. Available at . Accessed May 2021.Matthews, William A. et al. “The role of California and Western U.S. dairy and forage crop industries in Asian dairy markets.” International Food and Agribusiness Management Review. Special Issue. Vol. 19, Iss. B. 2016 at 156; Putnam, Dan et al. “The importance of Western alfalfa production.” 29th National Alfalfa Symposium Proceedings. December 1998 at 6.Putnam et al. (1998) at 3 and 5.Richter et al. (2020) at 322; Olson-Sawyer, Kai. “Dairy, drought and the drying of the American West.” Salon. October 29, 2022.California Department of Food and Agriculture. “California Agricultural Statistics Review, 2021-2022.” 2022 at 114.[1] Nilsen, Ella. “Wells are running dry in drought-weary Arizona as foreign-owned farms guzzle water to feed cattle overseas.” Arizona’s Family. Updated December 29, 2022; Koch, Natalie. “Arizona is in a race to the bottom of its water wells, with Saudi Arabia’s help.” New York Times. December 26, 2022.Richter, Brian et al. [Supplemental materials]. “Water scarcity and fish imperilment driven by beef production.” Nature Sustainability. Vol. 3. April 2020 at 5; Farah, Troy. “US rivers and lakes are shrinking for a surprising reason: Cows.” Guardian. July 2, 2020.Cantor, Alida A. et al. “Changes to California alfalfa production and perceptions during the 2011-2017 drought.” Geography Faculty Publications and Presentations. Vol. 238. 2022 at 20 to 22.Ibid.; Matthews et al. (2016) at 152 and 155.Water & Tribes Initiative. [Issue brief]. “The Status of Tribal Water Rights in the Colorado River Basin.” April 2021 at 1; Fonseca, Felicia. “State of unease: Colorado basin tribes without water rights.” Associated Press. September 15, 2022.Sakas, Michael Elizabeth. “Historically excluded from Colorado River policy, tribes want a say in how the dwindling resource is used. Access to clean water is a start.” Colorado Public Radio. December 7, 2021.Colorado River Research Group. “Tribes and Water in the Colorado River Basin.” University of Colorado Law School, Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment. June 2016 at 3; Swanson, Conrad. “What part do Native American tribes play in fixing the Colorado River shortage?” Denver Post. Updated January 4, 2023.Swanson (2023).Fonseca (2022).Ibid.Ibid.Swanson (2023).Ibid.Glennon, Robert. “What is dead pool? A water expert explains.” The Conversation. Updated May 13, 2022.Ibid.; Partlow (2022).Partlow (2022).[1] Ibid.; Jacobo, Julia. “Here’s what will happen if Colorado River system doesn’t recover from ‘historic drought.’” ABC News. April 19, 2023.Jones, Benji. “The Colorado River drought is coming for your winter veggies.” Vox. August 20, 2022.Barker, Burdette et al. “Agricultural irrigated land and irrigation water use in Utah.” Utah State University, Irrigation Extension. Accessed May 2023; McNeece, Brian. “Wyoming: Unhappy in its own way at the top of the Colorado River.” Desert Review. Updated January 12, 2023; Nevada Department of Agriculture. “Agriculture in Nevada.” Available at .Jones (2022).Jones (2022).Ibid.City of Chicago, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “Climate impacts on agriculture and food supply.” Available at . Accessed June 2023.FWW analysis of U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center. “Glen Canyon Dam near Page, AZ.” Available at . Accessed July 2023.Partlow (2022); Jones, Benji. “These 8 species depend on the Colorado River. What happens as it dries up?” Vox. Updated April 21, 2023.Ibid.[1] Lohan, Tara. “Left out to dry: Wildlife threatened by Colorado River Basin water crisis.” Revelator. September 12, 2022.Iknayan, Kelly J. and Steven R. Beissinger. “Collapse of a desert bird community over the past century driven by climate change.” Parks Stewardship Forum. January 6, 2020 at abstract.Cruz-McDonnell, Kirsten and Blair O. Wolf. “Rapid warming and drought negatively impact population size and reproductive dynamics of an avian predator in the arid southwest.” Global Change Biology. Vol. 22, Iss. 1. September 14, 2015 at abstract.Cowie, Robert H. et al. “The Sixth Mass Extinction: Fact, fiction, or speculation?” Biological Reviews. Vol. 97. January 10, 2022 at abstract and 656 to 657.Richter, Brian et al. “Water scarcity and fish imperilment driven by beef production.” Nature Sustainability. Vol. 3. April 2020 at 321 and 325.Dieter, C.A. et al. USGS. DOI. “Estimated Use of Water in the United States in 2015.” Circular 1441. 2018 at Glossary at 59 and 61.Hansford Economic Consulting. “Diamond Valley GID Financial Model Feasibility Analysis.” June 2013 at Appendix A at 4; Sloan, Jim. University of Nevada, Reno. “How much water does alfalfa need?” 2009; Chan, Nancy et al. SRI International. “The Utah Golf Economy: Economic and Environmental Impact Report.” January 2014 at 21; Berrade, Abdel F. and Denis Reich. “Alfalfa irrigation water management.” In Pearson, Calvin H. et al. (Eds). (2011). Intermountain Grass and Legume Forage Production Manual. Colorado State University Extension TB11-02 at 2.Johnson, Renée and Betsy A. Cody. CRS. “California Agricultural Production and Irrigated Water Use.” R44093. June 30, 2015 at 18; Geisseler, Daniel and William R. Horwath. University of California, Davis. “Alfalfa Production in California.” Updated June 2016 at 2.FWW. “Big Ag, Big Oil, and the California Water Crisis.” February 2023.FWW. “Big Ag Fuels New Mexico’s Water Crisis.” July 2023.Griego, Tylee M. University of New Mexico. “When high-water-use neighbors move in: Farming pecans in Valencia County, New Mexico.” May 2022 at 28 to 29.Johnson and Cody (2015) at 18.40 CFR § 122.23.Mekonnen, Mesfin M. and Arjen Y. Hoekstra. University of Twente. “A global assessment of the water footprint of farm animals.” Ecosystems. Vol. 15. 2012 at 406 and 408.CA S.B. 1157 § 679 (2022).

These crops are first in line to be cut, while water-intensive nut acreage typically remains safe. Nut trees are more valuable for farmers and require long-term investments, leaving them as favored crops to receive water in times of shortages.

These crops are first in line to be cut, while water-intensive nut acreage typically remains safe. Nut trees are more valuable for farmers and require long-term investments, leaving them as favored crops to receive water in times of shortages. Endangered Wildlife of the Colorado River

Endangered Wildlife of the Colorado River