Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

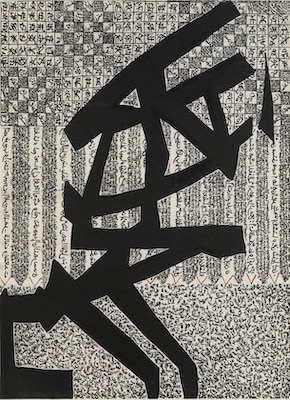

Laila Shawa (Palestine), Target 2009, 2009.

More than 10,000 Palestinians have been killed by Israeli armed forces in Gaza since 7 October, nearly half of them children, according to the most recent report by spokesperson for the Gaza Ministry of Health Dr Ashraf Al-Qudra. Over 25,000 others have been injured, with thousands still buried under the rubble. Meanwhile, Israeli tanks have begun to encircle Gaza City, whose population was 600,000 a month ago but whose neighbourhoods are now largely vacant due to the desperate flight of its inhabitants to Gaza’s southern shelters and due to Israel’s killing of thousands of Palestinian civilians in their homes. Israel has cut off the city and begun to raid it, going door to door to bring the terror of the occupation from the skies to the streets. Those who await these raids in their homes might whisper the poem of Mahmoud Darwish (1941—2008), which is addressed to the Israeli soldier ready to kick down the door of a Palestinian home:

You there, by the threshold of our door,

come in and drink Arabic coffee with us

(you may feel that you are human like us)

You there, by the threshold of our door,

get out of our mornings

so that we may be assured that

we are humans like you

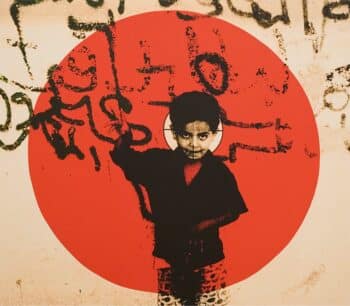

Belkis Ayón (Cuba), La cena (‘The Supper’), 1991.

When Israeli soldiers begin going door to door there will be no time for coffee, not only because there is no coffee or water left, but because Israeli soldiers have been told that Palestinians are not human. They have been told, instead, that Palestinians are terrorists and animals. In the eyes of the occupying forces, the only treatment Palestinians deserve is to be assaulted, shot, killed, and eradicated altogether. A hunger for genocide and ethnic cleansing colours senior Israeli officials’ statements and has influenced their conduct in this war. Talk of civilian casualties is brushed off, and so are calls for a ceasefire. The spokesperson of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) James Elder said of this situation: ‘Gaza has become a graveyard for thousands of children. It’s a living hell for everyone else’.

Even when high-ranking U.S. officials talk about a ‘humanitarian pause’, they continue to find billions of dollars and more weapons systems for the Israeli military. This idea of a ‘humanitarian pause’ is legalese that means nothing for the survival of Gazans: the pause would end the bombing for a short period of time, possibly only a few hours, to allow the wounded to be removed and some aid to enter Gaza City before giving Israelis a green light to resume their murderous bombardment. Thus far, Israel has dropped a higher tonnage of explosives on Gaza than the combined weight of the two bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

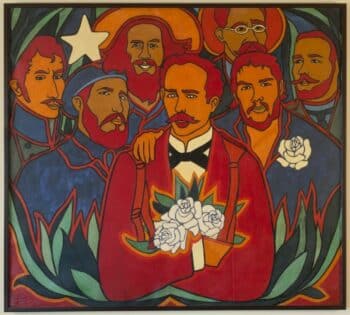

Raúl Martínez (Cuba), Rosas y Estrellas (‘Roses and Stars’), 1972.

The denial of both a ceasefire and the possibility of political talks sponsored by the UN is not a policy that the U.S. is pushing in Palestine alone; it is the same policy that the U.S., alongside its partners in the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), have insisted upon in Ukraine. A new supplemental spending bill that totals $105 billion (in addition to the—likely underreported—$858-billion military budget for 2023) includes $61.4 billion for the grinding war in Ukraine and $14.1 billion for the Israeli genocide of the Palestinians. Though peace talks opened between Ukrainian and Russian authorities in both Belarus and Turkey days after Russian troops entered Ukraine, these talks were hastily scuttled by NATO, fuelling the conflict that has resulted in nearly 10,000 civilian deaths so far. The civilian death toll in Ukraine during one year and eight months of the conflict has already been surpassed by the civilian death toll in Palestine in merely four weeks.

It is not a coincidence that these three countries—the U.S., Ukraine, and Israel—are the only ones that did not vote in favour of this year’s annual UN General Assembly resolution to end the six-decade-long U.S. embargo on Cuba (which was imposed formally by U.S. President John F. Kennedy on 3 February 1962 but began in 1960). The U.S. has not only enforced this blockade on Cuba as a country, but on the Cuban Revolution as a process. When the Cuban Revolution of 1959 emphatically declared that it would defend the sovereignty of Cuban territory and advance the dignity of the Cuban people, the U.S. saw it as a threat not only to its criminal interests on the island but also to its ability to maintain its grip over global affairs, which the potential contagion of the revolutionary process threatened to fracture. If Cuba could get away with looking after its own people, and even extending solidarity to others fighting for their right to do the same, before submitting to the demands of U.S.-owned transnational corporations, then perhaps other countries could adopt a similar attitude. It was this fear of sovereignty that set the policy of the blockade in motion.

Though the blockade has cost the Cuban Revolution hundreds of billions of dollars since 1960, it has not been able to stop the revolution from building up people’s dignity. For example, the World Bank reported that in 2020, despite the harsh blockade and the COVID-19 pandemic, Cuba’s government spent 11.5% of its Gross Domestic Product on education, while the U.S. spent 5.4%. Not only are all schools free for Cuban children, but all Cuban children receive meals at school and are given their uniforms. Medical education is also free in Cuba, creating a high doctor-to-patient ratio of 8.4 physicians and 7.1 nurses for every 1,000 Cubans. At the UN General Assembly, Cuba’s Foreign Minister Bruno Rodríguez Parrilla said that ‘attention to the human being has been and will continue to be the priority of the Cuban government’. The blockade might be ‘economic warfare’, he said, but the Cuban Revolution—which has faced this ‘economic siege’ for decades—will not wilt. It will stand firm.

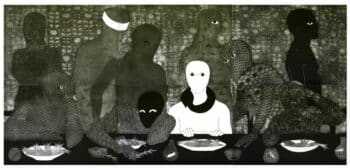

Tings Chak (China), Palestine Will Be Free, 2023.

The blockade is cruel. Foreign Minister Rodríguez Parrilla offered some examples of that cruelty, such as when the U.S. government prevented Cuba from importing pulmonary ventilators and medical oxygen (including from other Latin American countries). In response, Cuba’s scientists and engineers developed their own ventilators, just as they produced their own COVID-19 vaccines. During the pandemic, Rodríguez Parrilla said, the U.S. government offered humanitarian exemptions to other countries but denied them to Cuba. ‘The reality’, he said, ‘is that the U.S. government opportunistically used COVID-19 as an ally in its hostile policy toward Cuba’.

Darwish asks Israeli soldiers of humanity, of whether they are capable of seeing Palestinians as human. The same should be asked of U.S. government officials who promote and prosecute the blockade on Cuba: do they see Cubans as human?

In June of this year, the Paris Poetry Market invited the Cuban poet Nancy Morejón to be its 2023 honorary president. Just before the event, the organisers of the poetry festival cancelled this honour, saying that they were responding to ‘pressures’ and ‘rumours’. The Cuban foreign ministry condemned this cancellation as part of the ‘siege of fascist hatred of Cuban culture’, another kind of blockade. Here is Nancy Morejón’s Réquiem para la mano izquierda (‘Requiem for the Left Hand’), as if in conversation with the humaneness of Darwish’s poetry and with the rhythms of the Cuban musician Marta Valdés (to whom this poem is dedicated):

On a map you could trace all the lines

horizontal, vertical, diagonal

from the Greenwich meridian to the Gulf of Mexico

that more or less

belong to our peculiarityThere are also big, big, big maps

in your imagination

and endless globes of the Earth,

MartaBut today I suspect that the tiniest, most minute map

sketched on school notebook paper

would be big enough to fit all of history

All of it.

Warmly,

Vijay