… because I don’t love the oppressed. I love those whom I love, who are always beautiful and sometimes oppressed, but who always rise up in revolt.

Jean Genet—The Miracle of the Rose

An almost sick anti-Arab racism is so present in all Europeans that we wonder if the Palestinians should count on our help, however small?

These words were written by Jean Genet in 1971, in his first major text dedicated to the Palestinians.1

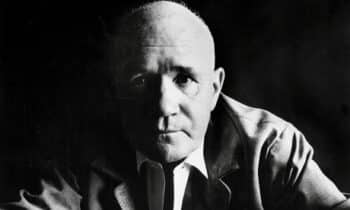

Genet was one of the most original and combative writers of the 20th century. Born in 1910 in Paris to an unknown father, he was handed over to public care by his mother at the age of seven months. One can imagine what enormous efforts this mother must have made to keep her child, since she kept him for his first seven months, probably abandoning him to an institution only when the struggle to keep herself and her child became an impossible task. Genet never met her. The authorities handed him over to be raised by a family of craftsmen in the small village of Alligny-en-Morvan. However, the bonds of affection that Genet could develop towards his adoptive family were also threatened from the outset, as he grew up knowing that when he turned thirteen, by law, he would be placed as an apprentice elsewhere, as indeed happened. At the age of fifteen, Genet ran away from the apprenticeship center where he had been taken and, as punishment, was imprisoned for the first time. From then on, a large part of his life would be spent in successive prisons.

At eighteen, he joined the armed forces as a way of escaping poverty and imprisonment. He served in the French colonial army in Morocco where he saw the brutal reality of colonialism first hand. Back in France in 1937, he was arrested several times on charges of vagrancy, desertion and, above all, theft. It was in prison, in 1942 and 1943, that Genet wrote his first novels, Our Lady of the Flowers and The Miracle of the Rose. In 1949, thanks to a petition launched by Jean Cocteau and Jean Paul Sartre and signed by several writers, Jean Genet was granted a pardon by the President of the Republic and left prison for good.

Genet never hid his homosexuality and his first books caused a scandal due to the frankness and freedom, unseen until then, with which he wrote about homosexuals and himself.

But it was in his writings in solidarity with the Black Panther Party and the Palestinian people in the fight against racism and oppression that Jean Genet left us a fundamental legacy and perhaps his most important message for our time.

Jean Genet in the United States

So, wherever I find myself, I will always feel linked to the movement that will bring about the liberation of men. Today and here, it’s the Black Panther Party, and I’m at their side because I’m with them.

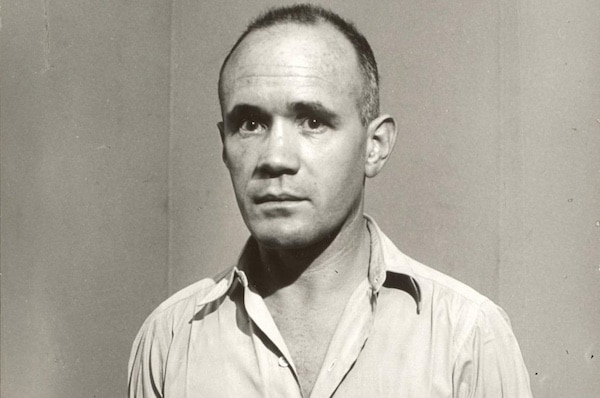

Jean Genet (Photo: logoskaitexni.blogspot.com)

In 1970, two emissaries from the U.S. Black Panthers went to France to ask Jean Genet, then a worldwide literary celebrity, to support their fight against racism. Genet’s play The Blacks had been a huge success in New York in the 1960s, running for four years, when only a few years earlier it had become possible by law for African-Americans and whites to attend the same theater in the United States. For a large part of the white audience, this play was a shock. But for the African-American spectators, Genet’s text was liberating and cathartic. For James Baldwin, Genet’s play was a revelation. Hence the Black Panthers’ interest in this white author who understood the reality of oppression and racism so well. In response to the Black Panthers’ appeal, Genet immediately proposed going to the United States.

The context of this 1970 visit is thus described by Genet’s American biographer, Edmund White2:

Nixon’s vice-president, Spiro Agnew, had vowed to wage merciless war on the Panthers, which he did with total conviction until he was ousted from office in 1972 for tax evasion. In Chicago and Philadelphia, police engaged in shootouts with the Panthers—or, more precisely, stormed their local headquarters. In Chicago, for example, on December 4, 1969, police raided the apartment of Fred Hampton, president of the Illinois Black Panthers. Peoria party leader Mark Clark and Fred Hampton were killed. Four other Panthers and two police officers were wounded. The police called it an exchange of shooting, but no bullet holes were found to support this version.

In reality, the police had been waging open war on the Panthers since the party’s creation, and by 1970 all the leaders (including Bobby Seale and Huey Newton) were dead, in prison or in hiding, with the exception of David Hilliard, the National Chief of Staff (who in 1992 was preparing a book on Genet’s friendship with the Panthers in 1970).

On April 2, 1969, twenty-one Panthers were arrested in New York and charged with conspiracy to stage explosive attacks on stores and public buildings. Sixteen were remanded in custody (with bail set at one hundred thousand dollars per person) for ten months until their trial, which opened in February 1970. It was against this backdrop that Jean Genet arrived in the United States. The Americans, he said, couldn’t stand ‘a red ideology in a black skin’ and had massacred twenty-eight Panthers over the previous two years.

In the USA, Genet gave several lectures accompanied by the Black Panthers at various American universities. There he drafted a ‘Letter to American Intellectuals’, which was widely circulated at those meetings and where he wrote:

For a white person, History, past and future, is very long, and very imposing in its system of references. For a Black man, Time is short. He cannot go back in his history beyond the periods of slavery. And in the U.S.A., we still strive to limit Blacks’ Time and Space. Not only is each of them increasingly entrenched in his or her own person, but we imprison them. When necessary, we murder them.

(…)

Faced with the vigor of their action (of the Panthers), and the rigor of their political thinking, the whites, and particularly this offshoot of the dominant caste in the USA, the Police, had a racial reaction: since the blacks were showing themselves capable of organizing themselves, the simplest thing to do was to discredit their organization.

In this way, the police were able to conceal the true meaning of their interventions behind unspeakable pretexts: drug, murder or vice trials. In fact, they wanted to massacre the leaders of the Black Panther Party.

In another speech, given on May Day in the USA, Genet said:

Another thing that worries me is fascism. We often hear the Black Panther Party talk about fascism, and white people have a hard time accepting the word. It takes a great effort of imagination for white people to understand that black people live under an oppressive, fascist regime. For them, this fascism is not just the work of the American government, but of the entire white community, which is truly privileged.

Here, whites are not oppressed directly, but blacks are, in spirit and sometimes in body.

Blacks are right to accuse the white community of this oppression, and they are right to bet on fascism.

We may live in a liberal democracy, but the Blacks do live under an authoritarian, imperialist, domineering regime. It’s important to communicate a taste for freedom among you. But white people are afraid of freedom. It’s too strong a drink for them. They have yet another fear, and it’s growing all the time, and that’s the fear of discovering the intelligence of black people.

What we call American civilization will disappear. It’s already dead, because it’s based on contempt. For example, the contempt of the rich for the poor, the contempt of whites for blacks, and so on. Any civilization based on contempt must necessarily disappear.

Jean Genet had a civilizing influence on the Black Panther Party. It was common in the Panthers’ language at the time to use adjectives referring to homosexuality as insults, revealing enormous prejudice. Jean Genet’s solidarity did not prevent him from seeing or denouncing the prejudices of the Black Panthers and demanding a change in behavior, which led one of the party’s most important leaders, Huey Newton, to take a written position. In an article written in prison, Newton had the admirable courage to confess his own unease in the presence of male homosexuals and to acknowledge that he felt threatened by them. Newton then stated that homosexuals were ‘perhaps the most oppressed people on the planet’, defended their dignity and demanded that the Panthers respect them and stop using pejorative and offensive terms in relation to homosexuality. This text by Huey Newton was extremely important for the fledgling gay liberation movement in the U.S. at the time.

Jean Genet and the Palestinians

His experience in the French army in Morocco very early on awakened Genet’s awareness of the reality of colonialism. He would later write a play that he himself called a ‘long meditation’ on the Algerian liberation war, The Screens.

The French far right at the time, especially through its armed wing, the O. A. S. (Organisation de l’Armée Secrète) carried out acts of terrorism in France against Algerians and anyone who supported the Algerian independence movement. Anticipating virulent attacks from the right and the extreme right, the producers of Genet’s new play decided to hold five openings instead of only one ‘premiere’ of the play The Screens in April 1966. This way, journalists could choose which one to attend. But on the night of April 30, a group invaded the stage of the play throwing bottles and a chair. From then on, every performance of the play was attacked in a similar way. On one occasion, a group, including a young Jean Marie Le Pen, tried to bar the audience from entering the theater by shouting. Years later, Jean Marie Le Pen would become the leader of the far right in France and the father of Marine Le Pen.

From his involvement in the anti-colonial struggles of the Arab people, it was only natural that Jean Genet would dedicate himself, in the last years of his life, to the Palestinian cause.

In 1971, about a year after his visit to the United States in support of the Black Panthers, Genet published The Palestinians, his first major text devoted to the Palestinian cause:

As for Israel, conceived at the end of the 19th century perhaps to offer security to the Jews, it soon became and remained, in this part of Asia, the most offensive Western imperialist threat.

(…) Let’s be clear: for the Palestinians, the enemy has two faces: Israeli colonialism and the reactionary regimes of the Arab world.

For Jean Genet, both the African Americans represented by the Black Panther struggle and the Palestinians suffered from the same colonial oppression, hence the similarity of their struggles and positions. In fact, a group of Black Panthers went to Palestine around that time to learn about their strategies and offer their solidarity and support, in a movement that aimed to unify all struggles against colonialism, including those within the U.S. itself. Jean Genet clearly understood and expressed that the anti-colonial struggle, as it still is today in Palestine, is inseparable from the struggle against imperialism.

The Shatila Massacre

The crucial moment in Genet’s experience of defending the Palestinian cause took place in Lebanon. In 1982, Genet returned to the Middle East ten years after his first visit, in the company of his friend Layla Shahid, head of the Journal of Palestinian Studies. Once again, I turn to Edmund White’s biography to contextualize the historical moment of Jean Genet’s visit:

When Genet arrived in Lebanon on September 12, 1982, after a ten-year absence, Beirut was calm. It was a crucial moment in the Lebanese war. Under siege for three months—the Israeli army was at the gates of the city—the Palestinian fighters, who had taken refuge in the western districts of the capital, had finally agreed to leave the country and be evacuated to Tunisia, Algeria and Yemen. The Palestinian camps were then disarmed and, on August 23, a new Lebanese president, Béchir Gemayel, was elected. The Palestinian civilians who remained in Lebanon were promised protection by an international force made up of American, French and Italian soldiers. (…) On September 13, Genet watched from the balcony (of the flat he was staying with Layla) as the international force departed. No sooner had the ships left port than, on September 14, the new president (who was also the leader of the Christian Right) was assassinated. The next morning, in violation of all agreements, the Israeli army entered Beirut ‘to maintain order’. The Israelis set out to hunt down the last remaining Palestinian fighters in the city, and that very evening took over the Sabra and Shatila camps on the outskirts of Beirut, setting up their headquarters in an eight-storey building two hundred meters from the entrance.

At 5 a.m. on Wednesday September 15, Israeli troops entered West Beirut. (…) Determined to sweep away the last vestiges of the Palestinians, the Israeli forces, under the command of General Sharon, made a secret agreement with the Phalangists, eager to avenge the death of Béchir Gemayel, which they attributed to the Palestinian secret service. The Israeli General Staff decreed, under the terms of Order No. 6, that ‘the refugee camps are off-limits, the search and cleaning of the camps will be carried out by the Phalangists of the Lebanese army’. A small unit of Phalangist militiamen, probably no more than a hundred and fifty men, entered Shatila and massacred all occupants under Israeli army projectors and flares. As Thomas L Friedmann, author of From Beirut to Jerusalem, concludes, ‘(…) Red Cross officials told me they estimated the total death toll at between eight hundred and one thousand’.

Jean Genet was one of the first to enter the refugee camp after the massacre. Here I reproduce parts of an interview Genet gave to Austrian journalist Rüdiger Wischenbart in Vienna about what happened:

R.W.: It’s said that it was more or less by chance that you were in Beirut at the time of the Sabra and Shatila massacres. How did you get to the Shatila camp and what did you see?

J.G.: No, I wasn’t there by chance, but invited by the Journal of Palestinian Studies. So, on Monday, I arrived in Beirut. On Tuesday, Béchir Gemayel was assassinated (…) The next day, Israeli troops crossed the Museum passage, moved through other parts of West Beirut and occupied the Sabra, Shatila and Borj el Barajneh camps, among others. The reasons they gave were to prevent a massacre. But the massacre took place. It’s difficult to say that the Israelis wanted this massacre. Indeed, I’m not sure. But they let it happen. It was carried out under their—as it were—protection, since they lit up the fields of Sabra, Shatila and Borj el Barajneh. When we send up flares, it’s so that we can see ourselves, to help our supporters. And Israel’s supporters were obviously the people who committed the massacre.

R.W.: There has been an Israeli parliamentary inquiry into responsibility. Are your observations, your on-the-spot investigation more or less identical to those of the parliamentary inquiry?

J.G.: The purpose of my visit and the purpose of this inquiry don’t coincide. Not at all. The purpose of the inquiry—from what I’ve read—was to save Israel’s image. Right. An image is useless. (…) So I don’t give a damn about the image. When the investigation was led by Israel, it wanted to save an image. I wanted to discern a reality, a political reality and a human reality. So, I can’t dwell on Israel’s aim with its investigation. Its investigation, in my opinion, was part of the massacre. Let me explain. There was the massacre, which tarnishes an image, and then there’s the investigation, which erases the massacre. Am I making myself clear?”

Genet wrote one of the most important texts of his last decade of life about what he saw in Shatila: Four hours in Shatila.

Jean Genet’s analysis, his indignation and the forceful clarity of his words can help us understand much more deeply what is happening in Palestine today. Nothing started now, everything has a history. And a history that is intertwined with other histories. In Jean Genet, the struggle of the Black Panthers is intertwined with the struggle of the Palestinians and above all with the struggle against colonialism, imperialism and its implicit racism, because the mythical superiority of the ‘white race’ has always been the central justification for both colonial oppression and imperial conquests.

For everything he saw, felt and expressed; for his courage and the clarity of his positions, Jean Genet remains our annoying and necessary contemporary.