Amid the present fateful developments in Palestine, it is worth turning back to an article of December 2006 by Jacob Levich,1 “A Counter-Revolution in Military Affairs? Notes on U.S. High-Tech Warfare” (at rupe-india.org; re-published here). It has proved remarkably prescient.

The article examined the United States’s ‘Revolution in Military Affairs’ (RMA),

a new system of warfare that was said to combine innovative battlefield tactics with high-tech weaponry, networked communications, and sophisticated surveillance technology…. ‘Wired’ or ‘postmodern’ warfare, it was widely claimed, would transform the 21st-century battlefield and assure American supremacy for generations to come.

Levich pointed out that so-called ‘precision munitions’ failed to reduce civilian casualties (they actually increased them). However, this was not of such concern for the U.S. and its allies such as Israel; the greater concern was that these weapons were ineffective in quelling guerrilla resistance. This was so particularly in Lebanon:

During the invasion of Lebanon, Hezbollah fighters were able to counter Israel’s U.S.-supplied smart bombs using classic guerilla tactics, digging in (a network of reinforced underground bunkers consistently thwarted precision weapons) or blending into the population as circumstances required. Nor were Israel’s high-tech targeting systems effective in locating small, easily portable weapons like Hezbollah’s Katyusha rockets….

… [A] rough evaluation of the bunker buster’s performance could be derived from the IDF’s 2006 attack on Lebanon. In July, the U.S. rushed 100 bunker busters to Israel as part of an effort to kill Hassan Nasrallah and the rest of Hezbollah’s leadership. The assassination targets, concealed to a depth of 40 meters in a network of hardened bunkers, emerged unscathed.

He argued that the construction and sustenance of such a network required popular support and involvement:

The tactics that defeated Israel’s high-tech munitions–construction of elaborate underground command centers and hardened missile sites throughout the country, lightning transfers of armaments and fighters in the face of Israeli bombardment, even the fighters’ ability to melt at will into the civilian population–required the sympathy and coordinated assistance of the people, often over years of painstaking preparation.

The U.S.’s elaborate infrastructure of electronic surveillance and reconnaissance (US C4I—Command, Control, Communications, Computers and Intelligence), designed for traditional battlefields, was not equipped to deal with guerrilla warfare by,

small, lightly equipped groups that are virtually undetectable by U.S. drones, or at worst indistinguishable from civilian traffic. Small-scale, highly efficient “hit and run” attacks (e.g., IEDs and sniper fire) are calculated to thwart U.S. drones; cellular organization and face-to-face communications are relied upon to outflank signals intelligence.

Moreover, the guerrilla forces were not averse to using technology themselves, albeit of a cheaper variety:

Even more disturbing to U.S. theoreticians, Hezbollah’s successful defense of southern Lebanon in 2006 provided evidence that a well-organized guerilla force can beat the high-tech West at its own game. Hezbollah flummoxed Israel’s satellite and overflight intelligence with decoys, developed counter-signals technology that cracked encrypted radio communications, and intercepted key battlefield information simply by listening in on IDF soldiers’ cell phone calls to their families.

Frustrated by their failure to ‘decapitate’ the leaderships of resistance in Iraq and Lebanon, the U.S. and Israel resorted to punitive air war:

As a result, the air war in Iraq has undergone a distinct shift over time from precision tactical bombing to strategic bombing intended to punish the people for their support of the resistance. A similar trajectory was followed, much more rapidly, in Lebanon, where the Israeli Air Force responded to the failure of its initial precision strikes against Hezbollah by widening the air war to civilian targets, including apartment buildings, airports, bridges, highways, and human beings….

Analysis borne out by October 7 and after

Source: BBC

Nearly all of these observations apply to the October 7 operation by Hamas and the ensuing developments. The following account draws on reports in the Washington Post, the Financial Times, the BBC, the New York Times, and Haaretz.

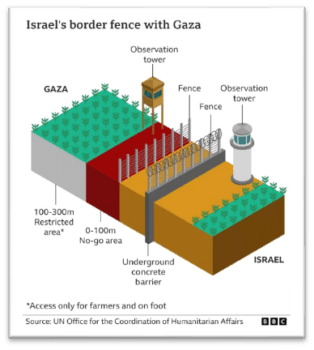

“Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had boasted for years”, says the Post, “of multimillion-dollar investments in an expansive ‘smart wall,’ running the length of the enclave above ground and extending deep into the ground.”2 Thermal imaging motion sensors, as well as optical and radar detection systems, gathered information regarding activity near the fence. This information was then communicated by a series of cell towers back to command posts. The cell towers also communicated with remote control guns along the border fence which would fire on anyone approaching.

This technological marvel enabled Israel to re-deploy its troops elsewhere:

Claiming in recent years that Hamas had been successfully contained in Gaza, Netanyahu oversaw the gradual withdrawal of troops from the south… In December 2021, Netanyahu tweeted that the installation of an “underground barrier that stops Hamas’s tunnel weapons” amounted to a “historic” day.3

Israel also drew confidence from another such triumph of technology, its ‘Iron Dome’ missile defence system, which intercepts and destroys short-range rockets and artillery shells, such as are fired by Hamas from Gaza and by Hezbollah from Lebanon. This system, developed by Israel with substantial U.S. funding, is celebrated for its effectiveness in countering missile attacks.4

The October 7 operation by Hamas and Islamic Jihad began with rocket fire from Gaza at around 6.30 a.m. This was not unusual, and rang no alarm bells for Israel; immediately followed the booms of the Iron Dome interceptor rockets, fired to knock out the incoming rockets. In fact, the Iron Dome booms were part of Hamas’s plan: they drowned out the sound of gunfire from Hamas snipers, who shot at the string of cameras on the border fence, and explosions from more than 100 remotely operated Hamas drones, that destroyed watchtowers. This was a coordinated action at 30 places along the border.

Once this simple technique had knocked out the smart wall’s detection systems, the entire ‘smart’ wall was disabled. Hamas’s special operations unit, the Nukhba, was able to breach the border with explosives and bulldozers, and drive through on trucks and motorcycles. In all 1,500 to 2,000 Hamas fighters made their entry.

From there, reports the Post, “it was less than a mile’s drive to the first military installations, which were mostly unguarded outside…. [F]ront-line observation troops were caught off guard when the militants stormed their bases, navigating confidently through facilities and barracks.”

“Their success wasn’t tech; it was preparation”

According to the New York Times, Hamas appears to have had “a surprisingly sophisticated understanding of how the Israeli military operated, where it stationed specific units, and even the time it would take for reinforcements to arrive.” In less than an hour, during which the Israeli army still had no clue of what had happened, Hamas fighters overran 8 Israeli bases. So rapid was their advance that, according to the Times, many Israeli soldiers were still in their beds and underwear. Says the Times:

In several bases, they [the Hamas units] knew exactly where the communications servers were and destroyed them, according to a senior Israeli army officer. With much of their communications and surveillance systems down, the Israelis often couldn’t see the commandos coming. They found it harder to call for help and mount a response. In many cases, they were unable to protect themselves, let alone the surrounding civilian villages.5

Upon reaching Israeli military’s regional command-and-control center, near Kibbutz re’im, a Hamas unit inflicted “complete destruction” of the base’s “communications systems, their antennas, even the systems that activated the sensors on the fence itself,” according to Lt. Col. Alon Eviatar, a former officer of Israel’s elite intelligence unit ‘8200’.6

Meanwhile, another Hamas unit attacked an 8200 installation near Urim, about 10 miles inside Israel-held territory. According to Eviatar, this was “the largest and most significant intelligence base in Israel, one of the country’s greatest assets”, synthesizing data from Israel, the Palestinian territories and around the world. The Times reports that the Hamas unit “knew exactly how to find the Israeli intelligence hub—and how to get inside.” They forced their entrance with explosives, and rapidly found their way to “a room filled with computers”. If any of these militants survived, and were able to carry away documents or equipment back to Gaza, it would be a blow to Israeli intelligence.

Upon reaching the settler colonies (kibbutzes), the Hamas units knocked out all communications first of all. They reached one such kibbutz a few minutes after the first rocket barrage at 6.30 a.m.. Before security guards could call for military reinforcements, the internet was cut off. The militants knew their way, and went directly to the head of security, who went into hiding. “Their success wasn’t tech; it was preparation,” said Miri Eisin, a former senior intelligence officer in the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF).7

The Times remarks that “The speed, precision and scale of Hamas’s attack had thrown the Israeli military into disarray, and for many hours afterward civilians were left to fend for themselves.” It took two hours for the Israeli military to declare a state of war.

Summing up the situation, Emily Harding, former CIA officer with expertise on the Middle East, and at present director of the Intelligence, National Security Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, concludes that “in October 2023 an overreliance on technology likely contributed to an intelligence failure.”8

Israel forces’ immediate response

Thereafter followed a hurried counter-attack by the IDF, on the ground and in the air. From a number of reports it appears that, whether for lack of information, lack of concern for the lives of Israeli civilians, or both, the Israeli armed forces killed a sizeable number of Israeli civilians in the course of their counter-attack. According to Middle East Monitor,

The Israeli news outlet, Yedioth Aharanoth, is reported saying that “the pilots realised that there was tremendous difficulty in distinguishing within the occupied outposts and settlements who was a terrorist and who was a soldier or civilian … The rate of fire against the thousands of terrorists was tremendous at first and, only at a certain point, did the pilots begin to slow down the attacks and carefully select the targets.”

Meanwhile, footage from inside kibbutzes shows absolute devastation resembling Israel’s repeated bombardment of Gaza over the years. Apache helicopter pilots have admitted to firing continuously without intelligence on targets, while tank crews were ordered to shell homes, regardless of Israeli hostages potentially inside.9

One of the survivors of Kibbutz Be’eri, Yasmin Porat, told an Israeli interviewer that, after the Hamas militants had taken a number of Israelis, including herself, hostage, Israeli Special Forces bombarded the place with tank shelling and indiscriminate gunfire. When asked whether the Israeli forces had thus killed the remaining hostages, along with two surrendering Hamas militants, she said “undoubtedly”.10 (A senior IDF tank commander is quoted elsewhere as saying “I arrived in Be’eri to see Brig Gen Barak Hiram and the first thing he asks me is to fire a shell into a house [where Hamas were sheltering].”11) Similarly, videos of the aftermath of the Nova electronic music festival show a very large number of cars which appear to have been destroyed from the air.12 It is even possible that, of the 800 Israeli civilians that Israel now estimates to have been killed on October 7, the greater number were killed by the Israeli army itself; we may never know the true figure, given that an impartial probe on the ground is ruled out.

It is true that the IDF earlier operated under the “Hannibal Directive”, which directed them to prevent the kidnapping of Israeli soldiers by all means, even at the price of striking and harming the kidnapped soldiers. The IDF claims that the Directive was replaced in 2016, but has not revealed the content of the new policy.13 Some commentators see in Israel’s present bombing campaign an extension of the Hannibal Directive to Israeli civilian hostages.14 However, whatever the influence the Directive had on Israeli forces, it is clear that their initial response to the October 7 operation was chaotic.

Ground war

This immediate response was followed by a phase of intensive bombing of Gaza by the Israeli Air Force, and raids on the territory by Israeli armoured vehicles and infantry. Then, on October 27, Israel launched a large-scale ground invasion of Gaza. While Israel’s army has a fearsome reputation, and it is armed with some of the world’s most sophisticated weapons, Israeli Major General Yitzhak Brik, a former military ombudsman, warned last August that it was “not ready for war”. Its soldiers have not fought a major land battle since 2014–the last time it deployed troops inside Gaza.15

The IDF estimates that Hamas has 40,000 highly trained fighters—a more than two-fold increase over its first battle with Israel in 2008-09. From reports, it appears there is a joint front between Hamas, Islamic Jihad and other Palestinian organisations with armed wings, such as the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP).

Hamas’s capabilities and level of motivation were displayed in the October 7 operation. Now, “As the IDF goes into Gaza, Hamas has the home advantage–and they’re ready,” cautions Devorah Margolin, senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East policy. Emile Hokayem, director of regional security at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London, says “It is also a learning organisation that has fought Israeli forces several times,” Hokayem said. “Hamas knows its terrain extremely well and will defend it fiercely and with ingenuity.”16

Hamas does not have an air force, so it cannot put up much resistance to Israeli bombing. Instead, it has adopted an old technology, one used to great effect by the Vietnamese against the U.S. armed forces there: a network of tunnels. The Financial Times reports:

Just as the Vietcong did in Vietnam, Hamas has turned Gaza into a fortress of barricades and mouse holes–including a 400km network of tunnels that Hamas fighters can shelter in during Israeli air strikes and use to attack Israeli forces from the rear. As Israeli troops move deeper into Gaza, Hamas is likely to try to use above-ground ambushes, quick strikes and camouflaged bombs to wear down Israel’s largely civilian army of reservists and bog them down in street fighting.17

Thus, as the Israeli newspaper Haaretz notes,

Hamas… is almost not attempting to block the movement of IDF forces. The organization is relying on its defensive tunnel network, sending its fighters up through shafts to launch anti-tank missiles and to deploy explosive charges close to IDF armored vehicles. Hamas is also employing attack drones. This may lead to several problems. The IDF has introduced large forces into the northern Strip, moving in large numbers of armored vehicles. This, in a war against guerilla forces hiding underground, provides the enemy many targets. Many of the confrontations are at the initiative of Hamas forces.18

The forces of Hamas and other Palestinian resistance groups operate in a decentralised fashion. “There is a sort of cellular military structure, where every company operates on its own.”19 All these reflect a study of the history of guerrilla warfare. “Hamas”, says Hokayem, “is more Vietcong than [it is] Isis.”20

High tech vs “stone age” tech

The battle between high and low tech can also be seen in the contrasting performance of the two sides’ intelligence machinery. Harding of CSIS remarks that “The Israeli services also would have been confident in their signals intelligence (SIGINT) collection. An attack this large took months of planning and coordination. Israel, leaning on its technological prowess, would have assumed a large attack would show up somewhere in technical surveillance: chatter over cell phones, emails over vulnerable lines, or someone who forgot to leave a cell phone outside a room when planning was discussed. But it seems a combination of strong Hamas defensive tradecraft and missed signs in collection meant a failure to warn.”21

According to the Financial Times report, Hamas combated ‘high tech’ by “going stone age”:

Another lesson that Hamas copied from other militant groups is the importance of secure communications. While Hizbollah has built its own fibre optic network, Hamas has maintained operational security by going “stone age” and using hard-wired phonelines while eschewing devices that are hackable or emit an electronic signature. One reason Israel was unable to predict the October 7 attack, said one Israeli official, was that it was listening to “the wrong lines”. Crucial military information was meanwhile shared either over that “analogue” system, or another encrypted system…22

Hamas’s ability to make preparations over a year, or even longer, and mount such a large operation—directly involving 1,500 fighters, and indirectly many more—without any leak of information is astonishing. It reveals not only that Israel lacks a network of operatives in Gaza, but that Hamas’s counter-intelligence is highly effective. With the benefit of hindsight, Harding points out that “A well-placed human source can provide facts, like who was in what room on what day, but can also interpret the significance…. An eventual Israeli intelligence review will reveal the collection posture for human sources. Gaza is a difficult operating environment—recruiting sources is hard and keeping them harder.”23

Hamas has addressed its difficulties in importing weapons by making its own armaments, and has “steadily improved the quality of its armaments, smuggling in components to convert dumb rockets into guided precision weapons…. According to Hamas, the group now makes ‘Mutabar-1’ shoulder-fired anti-aircraft missiles, which it says can take out Israeli helicopters, and ‘al-Yassin’ anti-tank rockets, which it claims can penetrate the reactive armour of Israel’s Merkava tanks.”24

On the internet, Hamas has put out a number of videos claiming to show its destruction of Israeli tanks and armoured vehicles in the present ground invasion. On November 12, the spokesperson for the Hamas’s military wing claimed that in all they had destroyed 160 Israeli military vehicles. Interestingly, these tanks and armoured vehicles appear at many places to be unaccompanied by ground troops. Is it that Israel prefers to use fewer ground troops, for fear they will get killed in street battles? However, this practice makes the tanks more vulnerable to attack by Hamas forces.25 For example, one video shows a Palestinian militant run up to a Merkava tank, plant an explosive charge, and run away before it detonates.26 According to the Clash Report twitter account, Israeli tank crews have now begun to “handicraft install simple cameras on their Merkava tanks in order to increase situational awareness in the absence of interaction with infantry and low visibility from the tank.”27

Most importantly, despite the best efforts of both the U.S. and Israel, no progress appears to have been made in the stated aim of the war, i.e., crushing Hamas. Haaretz doubts the Israeli army’s “ability to kill many Hamas fighters in ground battles. Some officers believe that reports of hundreds of dead terrorists are not sufficiently confirmed…. For now, despite pressure exerted by the IDF, there is no apparent significant effect on Hamas command and control, which continues to function.”28 Similarly, the New York Times reports:

It is not clear how effective Israel’s campaign against Hamas has been. One senior U.S. defense official, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive details, said the operations so far have not come close to destroying Hamas’s senior and middle leadership ranks. Other U.S. officials said Hamas is not analogous to Al Qaeda or the Islamic State, and has a far deeper bench of experienced midlevel military leaders, making it hard to assess the impact of killing any individual commander.29

“Punitive war”

And so Israel has resorted to what Levich in his article termed “punitive war”. This consists principally of large-scale Israeli airstrikes, now supplemented by a ground invasion. It is estimated that by the start of November Israel had dropped 18,000 tonnes of bombs on Gaza30—outdoing the nuclear bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

The results of Israel’s air strikes are summarised by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Palestine (as on November 10, 2023). The fatality toll reported by the Ministry of Health in Gaza stands at 11,078, including 4,506 children and 3,027 women. About 2,700 others, including some 1,500 children, have been reported missing and may be trapped or dead under the rubble. Another 27,490 Palestinians were reported injured. The fatalities further include 101 UN Relief and Works Agency staff; this is the highest number of UN personnel killed in a conflict in the history of the organization.

Over 1.5 million people in Gaza are estimated to be internally displaced. Gaza remains under a full electricity blackout since 11 October, following Israel’s halt of its power and fuel supply. On 9 November, following a few days of limited operation, all municipal water wells across the Gaza Strip had toshut down again due to the lack of fuel. UNRWA facilities are overwhelmed, with one toilet per 160 persons and one shower per 700 persons. Since mid-October cases of diarrhea, mostly among children under five, have risen more than 16 times.

The reported fatalities since 7 October include at least 192 medical staff. Since 9 November afternoon, Israeli bombardments around hospitals in the north intensified. The vicinity of Shifa hospital was hit five times during this period, with at least seven fatalities reported, along with damage to the maternity ward. On the evening of 9 November, buildings surrounding the Indonesian Hospital, in Beit Lahiya (northern Gaza), were repeatedly bombarded from the air, resulting in deaths and injuries. Around the same time, the Rantisi Hospital in Gaza city was directly hit, causing fires and damage. In the early hours of 10 November, the vicinities of Al Awda hospital in Jabalia, and Al Quds hospital in Gaza city were bombarded; the intensive care unit at the latter sustained damage.

Balance of forces, military and political

To fully appreciate the extent of imbalance of military forces, one needs to keep in mind that the war on Gaza is not being waged by Israel alone. Haaretz reports that “Over the past two weeks, close to 80 cargo U.S. military planes have landed in the region, in addition to dozens of civilian aircraft retained by the U.S. and Israeli defense establishments…. Open-source information reveals even larger numbers of U.S. military transport aircraft being used to deploy troops, equipment and armaments throughout the Eastern Mediterranean.”31 Apart from U.S. military and financial aid to Israel, U.S. Special Forces are on the ground in Gaza. The U.S. is flying drones over Gaza to assist Israeli targeting, and U.S. military satellites have been redirected to monitor the enclave. The U.S. is also using aircraft on its two carriers in the Mediterranean to help collect additional intelligence, including electronic intercepts. The carriers are also meant to deter other armies, such as Iran’s or Hezbollah’s, from entering the war in support of the Palestinians. Senior U.S. military advisers have been sent to Israel to advise its military on the ground invasion; among them is a U.S. Marine three-star general earlier involved in U.S. operations in Iraq.32 Clearly, the U.S. military is gearing itself for a wider war.

In the face of this imbalance of military forces, Hamas may be relying on other factors in its favour, which are less military than political. The principal such factor is public sentiment around the world, and particularly in the region. Despite the efforts of the largely Western-dominated global media, and despite efforts by several governments to suppress the expression of contrary views, pro-Palestinian sentiment has spread around the world at remarkable speed, and manifested itself in large rallies.

Israeli government officials have stated that they plan to make the war stretch out for several months, but unrest in the region at the developments in Gaza may not allow such a leisurely pace. The U.S. is facing increased opposition and attacks in the region. Between October 7 and October 27, more than 1,400 demonstrations took place in the Middle East and North Africa region in protest against Israeli actions and in solidarity with the Palestinians.33 Moreover, a U.S. defence official told Fox News that, between October 17 and November 9, there were 46 attacks on U.S. military bases in the region, largely in Iraq and Syria.34

Indeed, the U.S. appears to be worried at the impact of the Gaza invasion on its broader hold on the region. In the month after October 7, U.S. Secretary of State Blinken has shuttled between all the West Asian capitals—Egypt, Jordan, Israel, Bahrain, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Cyprus, Turkey, and Iraq.35 Guy Laron, lecturer in international relations at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, says that “the rage in the Arab world is so intense among the public that governments like Jordan and Egypt [are] feeling the political earthquake of October 7.” U.S. officials believe there is a “high risk of a Middle East conflagration. Hence the Biden administration’s insistence to the Israeli war cabinet on planning.”36

Notes:

- ↩ Levich tweets on the social media site “X” as “@cordeliers”.

- ↩ Shira Rubin and Loveday Morris, “Speed, coordination powered Hamas strike”, Washington Post, October 28, 2023.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ However, it is unable to fully block attacks by swarms of missiles. Moreover, the system works by firing interceptor rockets, and stockpiles of these rockets tend to run out after fielding a large number of missile attacks. Between October 7 and November 1, Hamas fired only 8,500 of of its stockpile of 30,000 rockets; in response, Israel ran down its supply of interceptors to the point where the U.S. had to fly in replacements. And while such swarms are cheap for Hamas or Hezbollah to produce, the Iron Dome interceptor rockets are expensive.

- ↩ Patrick Kingsley and Ronen Bergman, “The Secrets Hamas Knew about Israel’s Military”, New York Times, October 13, 2023.

- ↩ Rubin and Morris, op. cit.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ Emily Harding, “An Overreliance on Technology”, in “Experts React: Assessing the Israeli Intelligence and Potential Policy Failure”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 25, 2023, www.csis.org

- ↩ “Report: 7 October testimonies strike major blow to Israeli narrative”, www.middleeastmonitor.com

- ↩ Ali Abunimah and David Sheen, “Israeli forces shot their own civilians, kibbutz survivor says”, The Electronic Intifada, October 16, 2023, electronicintifada.net

- ↩ Peter Beaumont, “Israeli tank commander hailed as hero after Hamas attack is killed in Gaza”, Guardian, November 2, 2023. The commander goes on to say “The first question that comes to your mind is—are there hostages there? We did all the preliminary checks before we decided to fire a shell into a house.”

- ↩ Associated Press, “Israeli rave survivors return to look for cars after Oct. 7 Hamas attack”, www.youtube.com

- ↩ en.wikipedia.org, accessed November 12, 2023.

- ↩ Urooba Jamal, “What’s Israel’s Hannibal Directive? A former Israeli soldier tells all”, Al Jazeera, November 3, 3023.

- ↩ Mehul Srivastava, John Paul Rathbone, and Raya Jalabi, “Military briefing: How Hamas fights”, Financial Times, October 31, 2023.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ Amos Harel, “Despite Israel’s Fierce Attacks, Hamas Leadership Maintains Control on Gaza”, Haaretz, November 6, 2023.

- ↩ Srivastava et al, op. cit.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ Harding, op. cit.

- ↩ Srivastava et al, op. cit.

- ↩ Harding, op. cit.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ twitter.com

- ↩ twitter.com

- ↩ twitter.com

- ↩ Amos Harel, op. cit.

- ↩ Adam Entous, Eric Schmitt, and Julian E. Barnes, “U.S. Officials Outline Steps to Israel to Reduce Civilian Casualties”, New York Times, November 5, 2023.

- ↩ Zoran Kusovac, “Analysis: Israel’s Gaza bombing campaign is proving costly, for Israel”, Al Jazeera, November 3, 2023.

- ↩ Avi Scharf, “OSINT Shows U.S. Deploying More Arms and Troops to Israel, Cyprus and Jordan”, Haaretz, October 24, 2023.

- ↩ AFP and Jacob Magid, “US sends senior army officers to Israel to advise IDF on Gaza ground operation plans”, Times of Israel, October 24 2023.

- ↩ Infographic: Global Demonstrations in Response to the Israel-Palestine Conflict, www.foxnews.com

- ↩ Greg Norman, “46 reported attacks on U.S. bases in wake of Israel-Hamas war: official”, Fox News, November 9, 2023, www.foxnews.com.

- ↩ Tim Sahay and Guy Laron, “October War”, Phenomenal World, November 9, 2023, www.phenomenalworld.org

- ↩ Ibid.