In 1995, Massachusetts Governor William Weld pardoned Joseph Yandle who was then serving a life sentence for first degree murder, stating that Yandle had gone to “serve his country in Vietnam” and “returned a scarred man, and he has served a lengthy prison sentence. [23 years to that point].”

A year earlier, Mike Wallace had done a story on Yandle for 60 Minutes in which he reported that Mr. Yandle had served two tours in Vietnam as a Marine and “came home with a Bronze Star for valor, two Purple Hearts and something else, too: a heroin habit.” That Vietnam-acquired habit had allegedly led him into crime that included a string of armed robberies and cost the life of a liquor store clerk, Joseph Reppucci, in a 1972 holdup that Mr. Yandle helped a partner commit.

A year earlier, Mike Wallace had done a story on Yandle for 60 Minutes in which he reported that Mr. Yandle had served two tours in Vietnam as a Marine and “came home with a Bronze Star for valor, two Purple Hearts and something else, too: a heroin habit.” That Vietnam-acquired habit had allegedly led him into crime that included a string of armed robberies and cost the life of a liquor store clerk, Joseph Reppucci, in a 1972 holdup that Mr. Yandle helped a partner commit.

After the airing of the 60 Minutes story, W. G. Burkett, a Dallas businessman writing a book about veteran imposters, uncovered discrepancies in Yandle’s story and Yandle was forced to admit that, while he had served in the U.S. military during the Vietnam War, it was as a clerk with the Marines on Okinawa, and he did not win any combat medals.

According to Jerry Lembcke, a sociologist at the College of the Holy Cross (Worcester, MA) who has just published the book The Cult of the Victim-Veteran: MAGA Fantasies in Lost-War America (New York: Routledge, 2024), Yandle’s story is significant because it exemplifies a manufactured veteran-as-victim narrative that has ominous political implications.

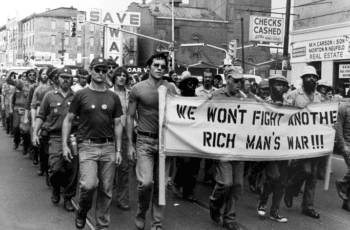

Vietnam veterans protesting against the war—a reality that has been widely forgotten, replaced by the image of the veteran as victim. [Source: legaleaglesflyordie.com]

However, a new diagnostic category was then invented—Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)—which pathologized veteran dissent and almost all veteran behavior.

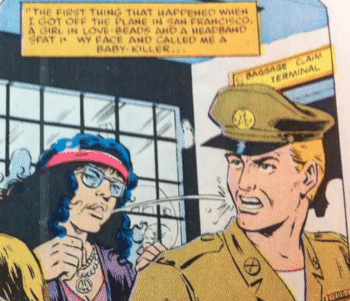

Veterans were reimagined in American political culture as victims of the Vietnam War who had been literally spat upon and betrayed by anti-war activists.

In reality, the notion of veterans being spat upon was an urban legend: Lembcke’s research uncovered few if any such incidents ever took place. Additionally, Lembcke found that a large number of veterans claiming to have been suffering from PTSD had never even served on the war’s front lines. The Christian Science Monitor claimed in 1991 that 50% of Vietnam veterans suffered from PTSD when only 15% saw combat.

Today, PTSD has become something of a badge of honor for veterans serving in illegal wars for which there are no battlefield heroics, especially since the U.S. military relies increasingly on automated weapon systems and drones.

Vietnam veterans march against the war in Washington, D.C., in April 1971. [Source: vintag.es]

This resembles Nazi Germany, which adopted the dolchstoss myth scapegoating Jews, communists, women, liberals and pacifists for Germany’s defeat in World War I.

Lembcke says that the invention of the psychiatric condition of shell shock in World War I—like PTSD after Vietnam—helped create the illusion that veterans were victims whose betrayal on the home front had to be avenged.

In the American context, revenge would come by fighting and winning new wars, by expunging domestic enemies, and by restoring America’s supposed cultural vitality from the World War II period—before the treasonous 1960s movements softened and “feminized” America.

GI Joe cartoon depicting a female hippie spitting on a soldier on his homecoming from the Vietnam War. Such a scenario never really occurred and was impossible in the way it was depicted. [Source: theworld.org]

Liberals have helped advance the veteran-as-victim narrative fueling revanchist policies because they have often framed criticisms of U.S. policy using the same mental health narratives as conservatives, suggesting that war harms the men and women sent to fight it.

This narrative obscures the far greater harm that U.S. wars have done to subject societies and imperialistic underpinnings of those wars, which liberals primarily support if the damage to American soldiers is not too great.

Discrediting Veteran Anti-War Voices

Lembcke is very critical of psychiatrists who supported the agenda of President Richard M. Nixon and other pro-war leaders beginning in the 1970s by adopting psychiatric labels to stigmatize non-conformist social behavior and veteran dissent.

At the 1972 Republican Party Convention in Miami Beach, Florida, the Nixon administration infiltrated Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) with agent provocateurs in an attempt to incite violence and make the veterans look crazy.

Tricky Dick [Source: wsj.com]

The Times had rejected Shatan’s piece 15 months earlier but found the timing opportune after months of widespread demonstrations by veterans, including ones where veterans hurled their medals at the Capitol building and admitted to being war criminals.2

In the late 1960s, a small group of psychiatrists had been working to formulate a new diagnostic concept that would apply to soldiers psychologically hurt by the Vietnam War, but they were dogged by the same empirical problems that had challenged the veracity of shell-shock during World War I—notably the fact that alleged “shell shock” sufferers were never exposed to exploding shells and there was no way of quantifying what soldiers were experiencing.

The psychiatrist Peter Bourne had reported objective comparisons of the levels of adrenal secretions associated with stress for combat and non-combat troops in Vietnam and found no difference among helicopter MedEvac crews.3 Bourne also found higher rates of psychiatric casualties among non-combat soldiers usually having nothing to do with the war.

VVAW members protesting outside the Republican National Convention in Miami Beach in 1972. [Source: floridamemory.com]

The cult of the veteran as victim was strengthened by attempts to play up the negative health impacts of Agent Orange on servicepersons, which remain unclear, and functions as a diversion from the vast devastation inflicted by the U.S. military on Indochina.4

Hollywood played a key role in the myth-making by caricaturing Vietnam veterans as psychologically damaged misfits and criminal junkies when sociological research determined that Vietnam veterans achieved higher socio-economic status than their non-veteran peers and used drugs only in tiny numbers.5

One of the films advancing misleading stereotypes was Coming Home (1978) starring famed anti-war activist Jane Fonda, whose character is having an affair with a paraplegic veteran played by Jon Voight, which prompts her husband (played by Bruce Dern), also a Vietnam veteran, to go into a rage and commit suicide. The impression created by the film was that all veterans were damaged psychologically by the war as one of its primary legacies.

Vietnam veteran hurling his medal at the U.S. Capitol building. Images like this were erased in popular culture and replaced with the archetype of the veteran as traumatized and psychologically damaged victim of the war, which in effect psychologized his protest if it was acknowledged at all. [Source: reddit.com]

This film has provided a metaphor for U.S. foreign policy ever since in its aim to avenge the “Vietnam Syndrome,” which was ostensibly provoked by weak-willed liberal politicians and the socio-cultural transformations bred by the 1960s movements that softened the nation’s moral fiber.

A Warped Political Culture

Analysts on the left have warned that the MAGA movement is fascist and Trump a wannabe Hitler or Mussolini.

While it is not clear that Trump has the same capabilities as those latter individuals, Lembcke’s book is significant in pointing to the deeply rooted sub-fascist themes in American political culture since the end of the Vietnam War that liberals have helped to advance as much as conservatives.

Labeling returning veterans as sufferers of PTSD may seem innocuous and well-meaning, but Lembcke spells out the real-world implications that sideswipe debate about America’s imperial role in the world.

It is part of a warped political culture that was used in the past to stigmatize and denigrate anti-war veterans and that transforms agents of empire into victims of traitorous domestic forces and a feminized culture that need to be eradicated.

Notes:

- ↩ The term PTSD wasn’t used in 1972, Shatan called it “Military Trauma.”

- ↩ After publication of Shatan’s piece, Shatan said that his phone began jumping off the wall, resulting in the organization of academic conferences and public forums followed by the formal professional adoption of PTSD by the American Psychiatric Association (APA).

- ↩Jerry L. Lembcke, The Cult of the Victim-Veteran: MAGA Fantasies in Lost-War America(New York: Routledge, 2024), 43.

- ↩ Science historian David Zierler concluded in a 2011 study that “epidemiological studies on U.S. veterans dating back twenty years have so far been unable to establish a conclusive link between Agent Orange [a chemical herbicide sprayed in Vietnam to deprive the enemy of jungle cover] and a variety of cancers and other health maladies that some servicemen have attributed to the herbicide.” Lembcke, The Cult of the Victim-Veteran, 62; David Zierler, The Invention of Ecocide: Agent Orange, Vietnam, and the Scientists Who Changed the Way We Think About the Environment (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010).

- ↩ See Jeremy Kuzmarov, The Myth of the Addicted Army: Vietnam and the Modern War on Drugs (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2009).