Concerns are rising for peace and sovereignty in the Pacific after strong signals from New Zealand’s new government that it wants to swiftly join the U.S.-led military alliance AUKUS.

If New Zealand does join the U.S.-led military bloc it would effectively compromise the country’s long-held anti-nuclear policy, Marco De Jong, historian and co-director of the New Zealand foreign policy group Te Kuaka, told Consortium News.

He said the decision would put an end to what is left of the nation’s independent foreign policy, as well as its image as an “honest broker” in a region already divided by increasing militarization.

The 2021 AUKUS agreement among Australia, the U.K. and the U.S. centers on the tripartite development of a nuclear submarine fleet within a security partnership geared to upholding the “rules-based international order,” as well as a “free and open Indo-Pacific.” Though not stated explicitly, it is seen as an anti-China alliance, based on a hyped-up threat of Beijing to the region.

It is controversial in Australia because the decision to join AUKUS with an AU$368 billion price tag for the submarines was continued by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese (following its initiation by the previous prime minister Scott Morrison) without any consultation with Parliament, let alone the public.

There is dissension in Albanese’s Labor Party, and former Labor Prime Minister Paul Keating, four days after the event in San Diego, publicly ripped the deal.

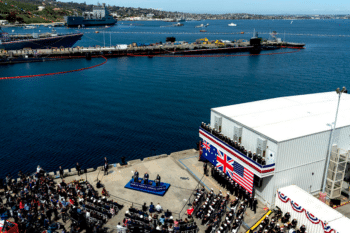

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, U.S. President Joe Biden and British Prime Minister Rishi Surnak at a press event for AUKUS in San Diego, March 13, 2023. (DoD photo by Chad J. McNeeley)

Keating said Australia was

now part of a containment policy against China. The Chinese government doesn’t want to attack anybody. They don’t want to attack us… We supply their iron ore which keeps their industrial base going, and there’s nowhere else but us to get it. Why would they attack? They don’t want to attack the Americans… It’s about one matter only: the maintenance of U.S. strategic hegemony in East Asia. This is what this [AUKUS] is all about.

By subordinating itself, Keating said Australia is forfeiting its sovereignty to rely on Britain, which abandoned its former colony years ago, to build nuclear submarines that serve U.S.–and not Australian–interests.

[See: A Sane Voice Amidst the Madness]Nevertheless the deal is still on track. It was announced in March that SNN-AUKUS nuclear submarines would be delivered to Australia by the early 2040s and the U.K. by the late 2030s.

A bill passed in the U.S. Congress on Thursday cleared the way to sell three-to-five Virginia-class submarines to Australia in the interim by the early 2030s.

New Zealand’s Path

Blinken with Hipkins in Wellington on July 27. (State Department, Chuck Kennedy, Public domain)

New Zealand now may be about to go down a similar path. The country’s government is one of the most right-wing in decades, a coalition made up of the centre-right National Party and two junior partners, including far-right libertarian party ACT and national party New Zealand First.

Early statements by ministers indicate its foreign policy settings will be much more closely aligned to the Anglosphere and U.S. geo-strategic interests.

Support for the centrist Labour government in October’s general election collapsed in the absence of any transformative intentions, as neoliberal monetary policy tackled inflation by imposing higher costs on the public while helping banks make record profits.

Pre-election, then Prime Minister Chris Hipkins stated he was open to conversations about joining Pillar II of AUKUS, reported to involve a non-nuclear brief, including integration of cyber, quantum computer technology and AI into military operations.

After U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken visited Wellington for talks in July, Hipkins emphasized Pillar II was only being considered as a “hypothetical” possibility, as it was still being defined.

Nuclear-Free

New Zealand became an anti-nuclear nation in 1987, declaring a Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament and Arms Control Act that effectively banned U.S. nuclear submarines from its waters.

It led to New Zealand being frozen out of the ANZUS security treaty and allowed the country to develop a more independent policy engagement with the Pacific and the rest of the world.

It has enjoyed good diplomatic relations with China, now its largest trading partner.

However, the U.S. is creating a security dilemma in the region as it attempts to contain peer rival China in its own sphere of influence, while forcing small nations to pick sides in the great-power competition now playing out.

Some Pacific leaders have already warned the U.S. quest for primacy is creating a destructive rivalry and dangerous geopolitical blocs in a region where peace has been underpinned by economic interdependence, regional cohesion and inclusivity.

New Zealand has at least 30 government agencies active in the region and its goal, as set on in its overarching Pacific Reset policy document, is to build a “stable, prosperous and resilient Pacific.” It has signed up to “Blue Pacific” principles of regionalism and Pacific-led solutions to challenges like climate change and economic development.

In a speech to the United States Business Summit in Auckland on Nov. 30, Foreign Minister Winston Peters repeated those goals, but said the U.S. was instrumental to the Pacific’s success.

Sending Signals

New Zealand’s Winston Peters with NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg in Brussels in 2018. (Flickr, NATO, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Both China and the U.S. have been investing in the region. China has been exercising its “soft power” by building infrastructure for nations on a “no strings” basis, while giving billions of dollars in foreign aid over recent years and offering loans on more favorable terms than those of Western financial institutions.

Peters said New Zealand wanted to “strengthen engagement with the U.S. on strategic and security challenges, centered on our common interest in a stable, peaceful and prosperous Indo-Pacific” by contributing to solving “international and regional security challenges, working alongside the U.S. and our many other partners.”

He added:

We know moving with the speed and intensity required to meet current challenges is going to require all of us to step up. New Zealand stands ready to play its part.

In a speech to diplomats on Monday, Peters also said the government would “vigorously refresh” security cooperation with Five Eyes partners U.S., Australia, Canada and the U.K.,

as well as with other key security partners in the region and beyond.

He claimed the previous government had created a Pacific “vacuum” that needed to be addressed urgently.

A day later his colleague, Defence Minister Judith Collins, was even more forthright, accusing the previous government of taking “an anti-American stance” and criticizing it for not having joined Pillar II already. [On that same day this week, however, New Zealand continued to oppose the United States in the U.N. General Assembly by voting for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza, joining Five Eyes partners Canada and Australia.]

New Zealand’s national Parliament, locally known as the Beehive, in Wellington. (denisbin, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The Government can sign up to Pillar II if the country’s attorney-general considers it compatible with the constitution, but would be expected to debate its merits in Parliament and seek cross-party support.

Kiwi Opponents

The new government’s aggressive signaling of intent has alarmed many, particular given the absence of public debate over the consequences of involvement in the alliance.

“I’m extremely concerned, mainly because neither major party campaigned on AUKUS,” de Jong told Consortium News. He said:

There was no clear consensus pre-election that this was something that would be pursued. The new Prime Minister [Christopher] Luxon has repeatedly stressed bipartisanship on foreign policy, so I think it’s profoundly undemocratic, to have a Foreign Minister from a minor coalition party signal something like this within the first week.

There has been no sustained public debate about what it can entail, about the opportunity costs, and that it’s something that Pacific nations don’t want. It’s something that Maori don’t want. Deeper integration with the military industrial base of the Anglosphere is something that we should be incredibly concerned about for New Zealand and its standing in the region and in the world.

Sharing this again, as New Zealand faces a generational foreign policy decision.

I have advocated against New Zealand involvement in AUKUS Pillar II this year in the belief that would weaken New Zealand and threaten our independent, nuclear free, and Pacific-led foreign policy. https://t.co/ti5iMMh72e— Marco de Jong (@MHdeJong) December 12, 2023

De Jong speaks for Kiwi opponents of joining AUKUS when he said it would ultimately add to a loss of sovereignty in the region generally, leaving New Zealand effectively rudderless in a sea of increasing militarization.

“If we can’t stand up for nuclear non-proliferation, if we can’t stand up for the rights of small states not to have to choose between superpowers, we stand to lose,” he said.

There is now a fear that a commitment to Pacific priorities and ways of doing politics will be jettisoned by New Zealand to accommodate a U.S.-led engagement in the region, one that has assimilated Australia with already destructive consequences.

A number of Pacific countries have recently faced deep internal tensions over defense pacts signed with the U.S. and Australia.

The Australia-Tuvala “faleipili” deal, signed in November, stands to give Canberra control of Tuvalu’s fishing rights and national security within its territorial waters. Negotiated in secret, without any public consultation, it has been slammed as an act of acceding sovereignty by former Prime Minister Enele Sopoaga.

Papua New Guinea was hit with protests in Moresby in May over the conditions of a maritime and defense deal with the U.S., which many also say compromises the nation’s sovereignty.

‘Bad Diplomacy’

“We see the AUKUS desire, that necessity to have unfettered access to Pacific lands and waters, causing regional political instability and if New Zealand goes down that AUKUS route, we can’t bully or buy our friends like Australia and the U.S. can,” de Jong said. “We can’t afford to do that. It’s bad diplomacy. It weakens New Zealand, and it jeopardizes our place in the region and it jeopardizes the long-held ties that M?ori and Pacific people have.”

It would also affect New Zealand’s nuclear-free policy. Signing up to Pillar II did not mean New Zealand would be excluding itself from involvement in nuclear warfare either, de Jong said.

Even though AUKUS pillar II has been portrayed as a non-nuclear element of the pact that involves technology sharing, critics point out the pact itself operates a military doctrine of nuclear war-fighting and that Pillar II suggests creating a single, integrated AI-driven system, where information might be exchanged between conventional and nuclear platforms.

Left-wing Indigenous party Te Pati Maori, which won six seats in Parliament in October, wants New Zealand to be non-aligned and to remain out of great power machinations underway.

Co-leader Rawiri Waititi told Consortium News his party feared for the nation’s sovereignty if AUKUS Pillar II was pursued. He called for a “democratic process” to be followed before any decision was made.

“We’re deeply concerned with the implications this has on Aotearoa’s independence and ability to remain militarily neutral,” he said, adding:

As Maori we cannot allow our sovereignty to be determined by others, whether they are in Canberra or Washington. Aotearoa should not act as Pacific spy base in the wars of imperial powers.

Joining AUKUS will severely undermine our country’s sovereignty, constitution, and ability to remain nuclear free. There is too much at stake for our government to make a commitment of this magnitude without a democratic process.

De Jong said the journey towards AUKUS involvement had been far from democratic. He talked of a process of “breadcrumbing” during the previous government’s tenure, where ministers had been led up a path of militarism by unelected securocrats pushing the pact as a rational political response to rising geopolitical competition.

Military Preparation

U.S. President Joe Biden, U.K. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Australia’s Albanese talking up their security partnership on March 13 at Point Loma Naval Base in San Diego. (White House)

In August the government released three defense, security and intelligence reports, all pointing to supposed threats faced by New Zealand amid rising tensions between an “increasingly assertive” and authoritarian China and the U.S., a traditional partner who valued openness and shared liberal democratic values.

The documents each set out moves the government was taking and should take to prepare militarily in defense of its sovereign interests and those of its partners.

Former Prime Minister Helen Clark at the time echoed de Jong’s concerns–that agenda-setting, faceless security officials were preparing the political ground for AUKUS.

“There must be sustained public debate,” de Jong said.

It is the most significant foreign policy decision in a generation. Not since New Zealand left AU in 1987 has there been such an important foreign policy decision and what we’ve seen is a shadow foreign policy from, in fact, that the deepening of ties with America has not happened with transparency or accountability.

There has been constant obfuscation and constant obstruction from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Mfat) on this matter, instead of public, sustained public engagement. What they’ve being involved in is an agenda-setting and threat escalating exercise, which serves nobody. Openness and transparency are not threats to democracy or national security. But a lack of openness and transparency, which in turn is a threat to our relationships with other countries.

We’re seeing the loss of sovereignty in multiple nations and we’ll end up that way too if we let a small cadre of defense and unelected officials determine our foreign policy in the shadows.

Geopolitical experts have increasingly talked of U.S. hegemony being under threat, particularly with the rise trading bloc BRICS-plus.

Several centers of economic and political power are now emerging out of a post-Soviet space of unipolarity of U.S. power, underpinned by a doctrine of “full-spectrum dominance,” defined by its policy makers as the ability to control any situation or defeat any adversary across the range of military theaters.

In order to maintain its hegemony, the U.S. has sought to contain its peer rivals leading the charge to multipolarity, namely Russia and China.

In the case of China, Taiwan is seen as instrumental in doing so. China views Taiwan as an integral part of its territory and is seeking “peace reunification” with the self-governing island.

U.S. has recognized the territorial claim under its One China policy as its official diplomatic position, while maintaining ‘strategic ambiguity’ to it. That position is becoming less ambiguous.

Many geopolitical observers believe the U.S. is seeking to prepare a proxy war in the Pacific as a means of weakening China’s power. It has stoked tensions by stocking up Taiwan with weapons while backing its independence movement, raising fears of a Chinese military intervention.

U.S. President Joe Biden has warned it will defend the island if China “invades.” The AUKUS alliance would play a key role in any confrontation.

A spokeswoman for the NZ Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Mfat) told Consortium News the Pillar II of AUKUS “included cooperation on emerging security issues, including areas (such as cyber) in which we already work closely with Australia, the U.S. and the U.K.”

She said officials were engaged with AUKUS partners to better understand the details of Pillar II, but decisions about possible participation would be for ministers in due course.

She added New Zealand was committed to supporting regional security and was already long-standing contributor to Pacific-led regional security mechanisms.

“In line with Pacific preference, we have been clear with all our international partners that engagement in the Pacific should take place in a manner which advances Pacific priorities, is transparent, is consistent with established regional practices, and supportive of Pacific regional institutions,” the spokeswoman said.

CORRECTION: AUKUS was initially agreed to by former Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison on Sept. 15, 2021 and Albanese decided to continue it, without public or parliamentary debate. Albanese vigorously defended the deal against internal opposition at the Labor Party conference in Brisbane this year.

Mick Hall is an independent journalist based in New Zealand. He is a former digital journalist at Radio New Zealand (RNZ) and former Australian Associated Press (AAP) staffer, having also written investigative stories for various newspapers, including the New Zealand Herald.