Thierry Deronne is a Belgian-born filmmaker who has long accompanied working-class and campesino struggles in Latin America. In the mid-1990s in Venezuela, he fostered popular media and educational projects, and later played a key role in the community television movement during the Bolivarian Revolution. Deronne is currently a professor at the National University of the Arts [Unearte]. His most recent documentary is Nostálgicas del futuro, a film about working-class feminism in Venezuela.

In Part One of this two-part interview, Deronne talks about the philosophy driving the community media movement earlier this century and the different experiments in communication that went along with it. In Part Two, Deronne will discuss the future of popular communication, and specifically his current project: the Escuela Popular de Cine y Teatro Hugo Chávez [Hugo Chávez Popular Cinema and Theater School].

Cira Pascual Marquina: You arrived in Venezuela in 1994, coming here from Nicaragua, where you had already cast your lot with Latin America’s struggles. Once in Venezuela, you worked with the Escuela de Formación Obrera (Working Class Training School) in Maracay, Aragua state. What can you tell us about that experience?

Thierry Deronne: The Working Class Training School was created by labor lawyers and feminists. It was both a crossroads and a meeting place: a multifaceted, open, and sometimes clandestine space for all those who felt that something had to give way here, that the country had to change.

There you could find labor leaders, women’s rights advocates, folks with links to the MBR-200 [Chávez’s first political party], people with roots in the historical struggles of the left, human rights lawyers, etc. We all came together there, organizing and participating in workshops, and meetings, writing documents and manifestos, and so on.

Among the folks who participated in the project was Jan Hool, a Dutch guy who was the school’s project coordinator but also secured some funding from a Dutch trade union. Eventually, with some of that Dutch support, we were able to launch the “Popular Film School” [Escuela Popular de Cine], where we organized workshops for activists, workers, women, campesinos, etc.

We would go to campesino settlements that were struggling for the land or to a community that was battling against a sprawling landfill. We would accompany feminist comrades who were giving workshops against gender-based violence and wanted to have the tools to represent themselves on film.

The school helped us highlight the role of women in the sphere of social reproduction, while aligning with a diverse tapestry of historical and contemporary struggles.

The Popular Film School grew, and even though the Working Class Training School in Maracay remained our center of operations, our project became a mobile one: we went wherever workers, women, or campesinos needed the tools to represent their struggles.

Teletambores was one of the first community television stations in Venezuela. (Teletambores)

CPM: Can you describe your work as a popular educator in more detail?

TD: We held workshops designed to fit the needs of the organized communities and helped document specific struggles. For example, we would join a group of campesinos and accompany their struggle by making videos documenting it, or we would organize a script-writing workshop with women and they would learn to tell their own stories through fiction, subverting the dominant and prescriptive soap opera style of narrative.

We also worked on recovering historical memory and documented worker strikes. In fact, we documented the last textile workers’ strikes in Maracay [in the late 90s]. It was a very important work stoppage, and we helped the folks striking to create an audiovisual portrait of the walkout and its participants.

In the documentary, the camera would move from the women who were cooking in the occupied factories, to the workers marching, then to the meetings and debates held among the folks on strike. We would sneak into the occupied factories at night, always in collaboration with the workers, and would record what they were doing.

This strike was a turning point for us: we went from the production of short documentaries, or short video reports, to making a full-blown documentary.

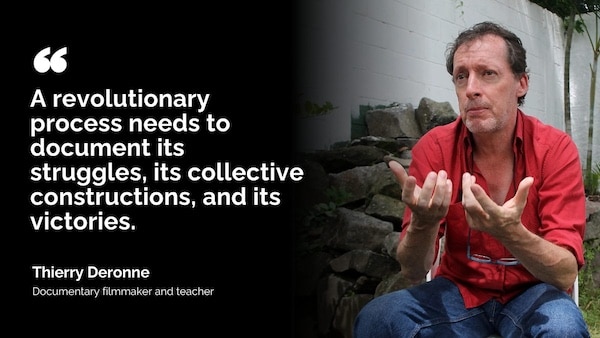

After that, we made the creation of a Venezuelan documentary school as one of our goals. A revolutionary process needs to document its struggles, its collective constructions, and its victories.

CPM: Around the year 2000, you founded Teletambores in Maracay, one of the first community television stations in the country. Can you tell us that story?

TD: We were doing a lot of work and it became clear that we needed to scale up our work to make the voices of campesinos, workers, and women’s groups heard. Back then, all television stations were commercial and they, of course, didn’t broadcast anything about workers’ struggles.

We put a TV antenna on the rooftop of Ana Santini’s home in the Francisco Linares de Alcántara barrio, which was in the suburbs of Maracay. Ana was a feminist comrade. José Ángel Manrique from the grassroots project TV Rubio, provided technical advice. That’s how we were able to begin broadcasting television in the barrio. We later got a second transmitter, allowing our signal to reach more of the city.

Sometime later, Blanca Eekhout and Ricardo Márquez of Catia TVe [a community television station in Caracas] came to Maracay to meet with us. That’s when the community television movement was born in Venezuela.

The constituent process that took place in 1999 laid a basis for an alternative kind of media and communication. Some representatives to the constituent assembly had promoted including the concept of “plural communication” into the new Magna Carta, and it got in. This eventually opened the door for a host of non-conventional communication projects.

The turning point for the community television movement, however, was during the 2002 coup, when community media had an important role in rolling back the coup was a wake-up call: corporate media was an overt weapon against the Bolivarian Process, so an alternative was needed.

This realization led to the writing of a new legal framework for telecommunications. It was developed in the offices of CONATEL [National Telecommunications Commission] with the participation of community media, including Catia TVe, Teletambores, and TV Rubio. For the first time, people who were not aligned with conventional media participated in the legal framework for a new form of telecommunications. It was extraordinary!

In that post-coup context, Chávez became a community media advocate. I remember a nice story: Catia TVe sent him a letter inviting him to inaugurate the community television’s new headquarters, but the new regulation hadn’t passed yet. Chávez was determined to attend, but CONATEL lawyers advised him against it, because the project was in a juridical limbo. So, Chávez defiantly declared: “If there isn’t a law, let’s make it!”

Stills from “Venezuela Adentro,” a Vive TV program that followed the people as they organized. (Vive TV)

CPM: The community television movement was very robust in the early years of the Bolivarian Revolution. What brought it together and what were its main objectives?

TD: Each community television had its own style, its own ways, its particular language and history. Nonetheless, there was one idea that brought us all together: the subject had to be the pueblo.

It may seem simple, but it was a total revolution! That objective brought with it a great deal of learning and a huge responsibility. Why? Community media was included in the new telecommunications regulation, but the new regulation bound us to present yearly educational plans to CONATEL, and we had to ensure that 70% of the production was in the hands of the community.

This meant that the community had to produce its own content. It was nothing short of an ideological revolution! From then on, the media organ itself was no longer the focus and its personnel were not the ones there producing content. Instead, the idea was to transfer the communication tools to the organized community. The community itself became the focus and generator of content.

It was important that all these achievements not become empty words: community media had to become a school. Why? If you don’t understand the tools, you cannot participate, and learning the technique does not happen spontaneously.

Teletambores had grown out of a documentary school committed to the rupture with the dominant audiovisual code, so people’s protagonistic participation was a given. This meant that the processes and timelines of production were different. First, we had to be with and among the people, and they would be the ones carrying out the research. The people would lead every stage of the production.

Second, we rejected all forms of sensationalism and audiovisual manipulation. Let me give you an example that still informs our current conception of documentary filmmaking. We view the sound-image relation in a nonconventional way. While interpretation and meaning are prescribed in mainstream productions through the interlinking of sound and image, we think that the relationship between the two should encourage the creation of meaning by the audience.

In our productions, there isn’t redundancy between image and sound, and this is conducive to more open readings. As we were exploring this method, we got a lot of inspiration from the Cuban Revolution and its emancipatory audiovisual language, which enabled audiences to be active co-producers of the message.

Bringing this back to Venezuela, we said: If the driving force of our revolution is the protagonistic participation of the people, then we can’t turn around and say that we are going to make community television, but to be more effective we will use the codes of Venevisión [Venezuela’s largest private TV station]. That would have been a legitimation of capitalism.

CPM: At the end of 2003, you went to Vive TV, a fledgling television station. Vive TV was a really extraordinary initiative back then. What was it all about?

TD: Vive TV was a state television channel that was there to broadcast the people’s voices. Shortly after its inauguration, Blanca Eekhout [president of the channel] asked me to help develop a new paradigm for the channel. That’s how the Popular Cinema School practically moved from Maracay to Caracas. Our goal was to create not just another station, but a new type of television.

It wasn’t easy because the whirlwind of creating the channel forced us to rely in part on compañeras and compañeros who came from commercial media, and they naturally came with some baggage. Different ideas were floating around about how to make television, but Blanca backed our proposal, and we were able to build something new.

There’s an old Marxist idea that technique and ideology can’t be separated, that each technique carries its own ideology. Marx’s proposal was that one day, instead of people working in a factory being just workers, or painters who paint all day being just painters, people would be able to do those things and many other things. This goes hand in hand with the workers’ movement’s historical idea of creative leisure.

Education was key at Vive TV, and that’s how we began to break with the old social division of labor. Everyone, from the camera person to the security guy, from the so-called management to the tech people, would participate in our workshops.

CPM: Tell us more about those workshops.

TD: We studied revolutions as well as documentary production and fiction to understand different dramaturgical devices. The objective was that everyone should have the tools to conceive and make audiovisual content not from a cubicle and just to fill a space on the broadcast schedule, but while spending a week with a group of campesinos.

The idea was that after spending a few days living alongside people struggling, Vive folks would come back with the footage and a clear idea of what the community needed in terms of audiovisual production.

We also promoted educational workshops in the communities and brought the communities themselves to the Vive TV studios. In those days, you could walk into a nicely lit studio and find a handful of INVEPAL workers talking about taking control of the paper-production plant or a group of campesinos discussing their reality in Barinas state.

Now, some fifteen years later, when I travel around Venezuela, I run into people who say: I can help out with sound or with the camera, I studied with you in Vive. Vive TV was a school, a seed that fell on a fertile ground in a country amid a revolutionary process.

CPM: You promoted non-conventional production at Vive TV. Can you talk about what kinds of programs were made there?

TD: We were trying to reinvent television, so there were different programs. We had the liberty and the resources to do it. It was a dream come true!

There was a program that was called “Venezuela Adentro” [Inside Venezuela], which had thousands of episodes. We were inspired by Santiago Álvarez of the ICAIC [Cuban Cinema Institute] and his “Noticiero Latinoamericano” [Latin American News Report], which was a weekly chronicle of the Cuban Revolution. They didn’t mince words in that news report: they dealt with the real problems that the revolution faced. It was very informative and humorous at the same time.

While it was sometimes critical, the Cuban Revolution had the maturity to protect the project. Every Sunday, Cubans sat down to watch it with more interest than the movie that followed it. That experience was an inspiration for “Venezuela Adentro,” where there was room to pursue critical positions within the revolution, and the pueblo was always the subject.

Chávez welcomed and even promoted criticism within the Bolivarian revolution. He would say: Seize the municipal governments, seize the regional governments! Change everything! This inspired us to go out into the world on horseback, to cross a river, to walk up a mountain.

Going back to Vive’s programming, I’ll highlight three additional programs that had a workshop format. First the “Philosophy Course” and the “Cinema Course.” We often had guests for our workshops, and we thought that it would be good for everyone to be able to see them. [Those two programs make the workshop available to the public.]

Finally, “En Proceso” was a program with a non-conventional format. A continuous camera take would follow the work of, for instance, a self-organized Urban Land Committee. The camera would follow the committee spokespeople visiting the homes in a barrio. The idea was to present reality as it is, without the cuts that do away with the so-called “dead times” when apparently not much is happening.