Lenin died 100 years ago. He was one of the towering figures in the Marxist tradition, who translated ideas into action by building a revolutionary party and leading a working-class revolution. It is important to have some grasp of who Lenin was—and of the times in which he lived—to make sense of his ideas, where these ideas emerged from, and what impact they made.

Lenin’s life, which was utterly bound up with his political work and the wider class struggle, can be roughly defined into the following phases:

Lenin’s formation as a Marxist, 1887-92

Nobody is born a revolutionary. Not even Lenin. He became a Marxist in Russian conditions in the late 1880s and early 1890s. Lenin reacted against the weaknesses of Narodism, a revolutionary movement mainly composed of students and intellectuals that adopted terrorist methods and aimed to liberate the peasantry. The massive Russian Empire was ruled by an autocratic Tsar with very little political freedom or democratic rights for its people.

Serfdom may have been abolished in 1861, but peasants had little control of the land on which they worked, while national minorities were brutally oppressed. The emerging capitalist economy was pushing up against antiquated feudal structures and the power of the landed aristocracy, but the new capitalist class feared the working class too much to risk leading a popular struggle against the old order.

For Lenin, the crucial element in breaking from the Narodniks was his discovery of the power of the emerging working class. Connecting the Marxist tradition (which has the self-emancipation of the working class at its core) with the real struggles of workers in cities like Petrograd and Moscow would become central to Lenin’s life’s work.

His early years building revolutionary organization, 1892-1905

By 1892, Lenin was committed to revolutionary socialism and convinced by Marxist analysis and arguments. From then until the revolutionary outbreak of 1905, he played an influential role in coalescing scattered and tiny Marxist study circles into a national organisation. It grew considerably and intervened in working-class struggles.

Lenin was heavily influenced by Plekhanov, the father of Russian Marxism, but he also made his own theoretical contributions, notably his writings on capitalist development in Russia in 1897-99. He also intervened heavily in debates among Russian socialists: for example, What is to be done?’ (1902) was a polemic against those he thought guilty of making concessions to ‘economism’, an approach that concentrated on trade-union issues to the exclusion of political perspectives, as well as an attempt to define the strategy and tasks of a revolutionary organisation. A major debate at the Third Congress of the Russian Social Democratic and Labour Party (RSDLP) led to a divergence between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, with Lenin emerging as leader of the former.

The revolutionary upheavals of 1905-07

All wings of the Russian socialist movement grew enormously in the wake of the Russian Revolution of 1905, which saw the emergence of radical new forms of working-class democracy, above all the Petrograd Soviet (or workers’ council). Lenin analysed such developments and generalised from them about the dynamics of mass struggle, the nature of workers’ power, and the goals of revolutionaries in Russia.

These upheavals were ultimately defeated, but they represented a massive challenge to the status quo. They radicalised a layer of workers and provided an experience that would prove valuable in 1917. This is why 1905 would later be referred to as ‘the great dress rehearsal’.

Building the Bolsheviks, 1907-14

The vicious counter-revolutionary repression, following the defeat of these workers’ rebellions, caused serious problems for revolutionaries like Lenin’s Bolsheviks. A process of patient party building was required in such challenging circumstances. Lenin had to navigate numerous tactical challenges, including how to relate to the very limited forms of democracy and political freedom in Russia.

Lenin argued relentlessly against those in the socialist movement who succumbed to opportunism (being pulled to the right, away from revolutionary socialist goals), but also against those ultra-left elements who wanted to stand aloof from elections and trade union struggles.

A fresh upsurge of workers’ resistance began in 1912, with a burgeoning strike wave that was only halted by the start of war. The Bolsheviks finally split from the Mensheviks in 1912—constituting themselves as an independent party, not merely a faction. In the same year, the Bolsheviks launched a daily paper, Pravda, which proved indispensable to building their strength among militant workers in the factories.

Opposing the war, 1914-17

The onset of war in August 1914 transformed European and Russian politics and, in the longer term, triggered major social convulsions. Crucially for Lenin and the Bolsheviks, it was the catalyst for the collapse of most European socialist parties into national chauvinism. Germany’s SDP (the dominant section in the Second International) led the way in backing its own nation-state’s war effort. The Second International effectively collapsed.

The Bolsheviks were unusual in adhering to anti-war, internationalist positions. They engaged in anti-war agitation, sought to link anti-imperialism with domestic politics, and forged connections with otherwise extremely isolated anti-war socialists in other countries. Lenin turned to the issues of imperialism and war—for example, in his 1916 book Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism— to provide a clear theoretical basis for anti-war socialist organising.

The revolutions of 1917

Revolution broke out in Russia in February 1917. It took just several days of huge demonstrations and mass strikes to topple the Tsarist regime. Soviets re-emerged in a bigger and more widespread form than in 1905, providing workers, peasants mutinous soldiers, and sailors with democratic arenas in which to put forward demands.

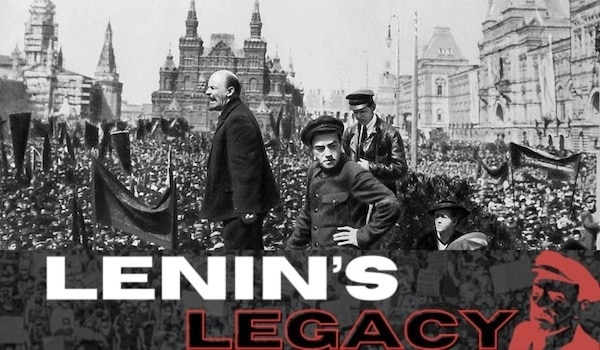

An unstable ‘dual power’ scenario emerged, with the Soviets offering a counterpoint to the newly formed Provisional Government led by pro-capitalist liberals. Lenin returned from exile in April 1917 (he had spent most of his adult life outside Russia). He shocked even many of his own supporters when he outlined the perspective that the working class must move ahead to social revolution and the seizure of state power, not limiting itself to the democratic reforms ushered in by the fall of Tsarism.

By October, the conditions were ripe for insurrection, which Lenin argued for doggedly within the leading bodies of the Bolsheviks. The insurrection in Petrograd marked the peak of the revolutionary struggle and led to the founding of the first workers’ state in history.

Leading a workers’ state, 1917-23

The new revolutionary government, headed by Lenin, did not delay introducing major changes. The Bolsheviks had called for land for the peasants, peace for the soldiers and sailors, and bread for the workers. Now they delivered on all these fronts: taking land into social ownership, pulling Russia out of the imperialist war, granting freedom for many of the national minorities, and introducing economic reforms rooted in socialist principles of cooperation and equality. There was a flowering of real democratic and personal freedoms too, challenging various forms of oppression—in particular the subjugation of women.

However, there were massive obstacles. Counter-revolutionary ‘White’ armies inside Russia were joined by military intervention from numerous European states, determined to crush the example of workers’ power and nascent socialism in Russia. Economic blockade and sanctions had a devastating impact.

Enormous resources had to be invested in protecting the new workers’ state through the civil-war period (1918-20). Many of the workers who had made the revolution were killed in the civil war, or deserted the cities for the countryside under huge economic pressure, or were drawn into the state apparatus.

Workers’ revolts happened in Europe, but none were as successful as Russia’s revolution. Russia was isolated. The strains and setbacks took their toll—the urban working class shrank, the Soviets became hollowed out and the state increasingly substituted itself for the working class. These conditions laid the basis for the appalling rise of Stalinism that followed Lenin’s death.

Lenin’s political career was ended by a debilitating stroke in March 1923. He died in January 1924.