This week on February 2nd, the U.S. Labor Department released its monthly jobs report for January. One of the Department’s two surveys showed +353,000 jobs created in January. But a second report shows a drop in total employment in January of -1,070,000 full time and part-time jobs (and an additional -400,000 jobs if one includes unincorporated independent contractors jobs. So, like the Bible, one can find whatever one wants in the government job stats.

So why the discrepancies between the two surveys in the monthly jobs report?

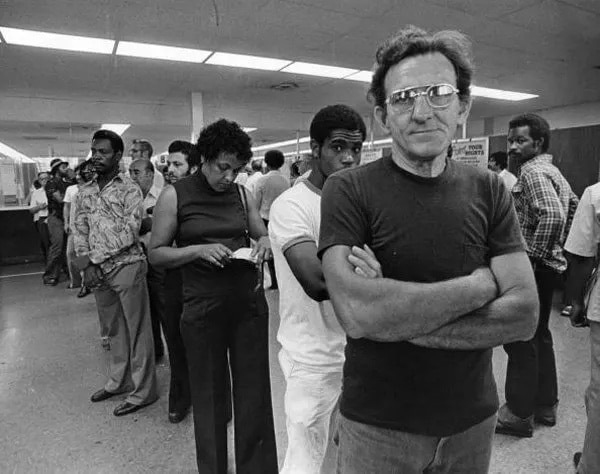

Jobs

One reason is that the two surveys have big differences in their methodologies (and underlying assumptions).

The Current Establishment Survey (which is not really a survey), or CES, is a compilation of reports provided by around 400,000 large businesses to the labor department. Even so, apparently those large corporations have been reducing their participation in the reporting. So maybe half that send in their reports on their hiring, layoffs, etc. to the government.

The second survey, the Current Population Survey, or CPS, is a true survey conducted by the labor department monthly. It actually surveys mostly smaller businesses. It has a different methodology than the CES and different assumptions.

If one uses the CES, it appears (and the Biden administration claims) 3.1 million jobs were ‘created’ in all of 2023. But the CPS survey shows only 820,000 (again, counting full-time, part-time, and unincorporated independent contract workers).

Part of the problem may be that the CES doesn’t count NET job creation, just new jobs, while the CPS looks at the total level of employment from period (January) to period (January). The latter makes more sense. Doesn’t one want to determine what the net gain in jobs was over the year? Jobs gained minus jobs lost? And isn’t a survey that considers the millions of smaller companies perhaps more accurate than a partial census with declining participation by bigger corporations? There’s a bifurcated U.S. economy out there. Big businesses may be doing okay; but smaller businesses generally aren’t.

Then there’s the matter of the unemployment rate monthly reporting. Here we keep getting a monthly unemployment rate of 3.7% (for the last three months). But that 3.7% is what is called the U-3 unemployment rate. That rate, unfortunately, is for full-time workers only! The U.S. civilian labor force is about 167 million. Maybe 40-50 million of that total labor force are part-time workers, temps, gig workers (grossly underestimate by the way), independent contractors (who are actually workers not small businesses), etc.

And if one looks at the CPS survey again, there’s a statistic called the U-6 unemployment rate. That’s at 8%, not 3.7%, in the January jobs report.

The U-3 concludes only 6 million workers are unemployed; the U-6 estimates almost 14 million are unemployed.

The mainstream U.S. media likes to hype and report the 353,000 January and 3.1 million 2023 jobs, and the 3.7% unemployment rate and 6.1 million jobless. You’ll see that published virtually everywhere. But elsewhere in the same government statistics there’s the -1,070,000 January and 820,000 2023 jobs and the 8% unemployment rate and the 14 million jobless.

It all comes down to what population you’re dealing with, what kind of survey you’re using (or not) and what are the scores of underlying assumptions (typically not noted in the reports) that are being employed in the methodologies chosen.

For example, when estimating U-3 jobs the government takes the raw data on jobs in monthly big business report (CES) then adds a separate set of raw jobs data from what it considers net new businesses created. These two datasets are merged (with certain assumptions about how many jobs on average are associated with a new business when it is created). It combines the two datasets, does a number of operations and manipulations on the raw data, including (but not limited to) seasonality adjustments, and comes up with the 353,000 reported, for example. But that 353,000 is a statistic, a manipulation and transformation of the actual raw data on jobs. Statistics are estimations of the actual data, not the actual number of jobs created in January. But this approach integrating new business formation job creation with the monthly large businesses reporting on jobs has certain real problems:

First of all, it is impossible to estimate net new business development. Why? There’s data on when a new business has formed. It must report formation to its respective state. But businesses rarely report anything when they go out of business. They simply go away. So the government plugs in a number based on historical trends for the number of businesses failing each month, subtracts that from the number newly started, and that’s the new business formation jobs total it then adds to the big businesses reports to the labor department. In other words, the ‘net’ is half made up, a plugged in number! Worse still, the ‘net’ supposedly jobs number is lagged at least six months from the current big business raw jobs number reported. So one’s estimating jobs ‘created’ six months ago and mixing it with current jobs reported.

Not only is this mixing apples and oranges but oranges and potatoes since the latter is not really a fruit.

Wages & Salaries

There are similar issues when the government says wages have risen 4.5% over the past year: that 4.5% is for full-time workers only. Moreover, it includes ‘wages’ (salaries) of the highly paid occupations, including managers and even CEOs salaries. The fact is these occupations at the top end of the ‘wage structure’ get wage raises much higher than 4.5%. So the 4.5% average is skewed to the top end. And that means workers at the median are likely getting less than 4.5%. Those below median even lower, unless they were at minimum wage and living in one of the states that raised minimum wages recently. If not, and living in the two dozen or so stuck with the federal minimum wage of $7.25 for nine+ years now, they got 0% raise.

In other words, reporting 4.5% is an average and that distorts reality.

There’s also the problem of what is the real take home pay wage and salary. The 4.5% is reported as adjusted for inflation. But what if the adjustment is, once again, only for full-time workers, which is the case for the oft-reported 4.5%. Even more important, what if the inflation adjustment is ‘low-balled’? The CPI price index latest results showed inflation of 4% for ‘all items’. That would suggest an average real wage gain of 0.5% last year. But has it been 4%. (Or the even lower 3.4% for the other price index, the PCE)? There are a whole set of other issues associated with the under-estimation of inflation—and thus overestimation of the 4.5% wage gain. That would require a separate article to fully consider and explain. To make it brief, this writer believes the corrected CPI is at least 6%, not 4%. If so, the real wage gain of 4.5% is actually a real wage decline of at least -2% last year.

When one looks at the overall growth of the economy year to year, or quarter to quarter, as measured by the Gross Domestic Product, GDP, another entire set of issues also arise. The official preliminary first GDP report released a week ago indicated GDP in 2023 rose by 2.5%.

GDP vs. GDI

Without considering all the issues why GDP is also over-estimated even at 2.5% (another article perhaps), here’s just one: GDP measures the total market value of all the goods and services produced and sold in a given year (or quarter). That total production results in a corresponding total income generated.

After all, if a product or service is sold (the definition), then it produces a revenue which gets distributed among various sources of income: profits, wages, etc. The gross income created from the gross production should be more or less equivalent. But the gross income for 2023 (called Gross Domestic Income, or GDI) was only 1.5% while the Gross Domestic Product, or GDP, was 2.5%! So where did the other 1% go? Either GDI is underestimated or GDP is overestimated, or both. Whatever, the media likes only to report GDP but it seems what ends up in people’s pockets (GDI) is more important.

The preceding is just an overview of some of the real issues behind U.S. statistics on jobs, unemployment, wages or even the economy’s growth in general that get glossed over or even ignored by the media and especially politicians. There’s a lot of ‘cherry picking’ of the statistics going on.

Perhaps that’s why in part the media, pundits and politicians keep scratching their heads recently, lamenting on why the American public doesn’t get it that ‘the economy’s doing really good’.

The U.S. political system is badly split, we are told. No doubt. But maybe the economic reality the U.S. public deals with on a daily basis differs so much from the selective statistics reported by the media there’s a split in perceptions of the actual U.S. economy as well?