Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

Oswaldo Vigas (Venezuela), Alacrán (‘The Scorpion’), 1952.

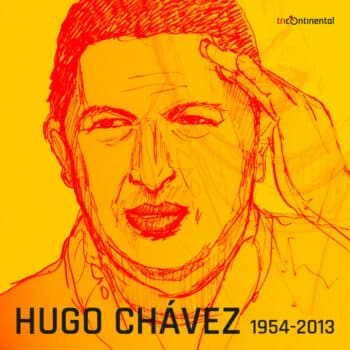

On 2 February 2024, the people of Venezuela celebrated the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Bolivarian Revolution. On that day in 1999, Hugo Chávez took office as the president of Venezuela and began a process of Latin American integration that—because of U.S. intransigence—accelerated into an anti-imperialist process. Chávez’s government, understanding that it would not be able to govern on behalf of the people and address their needs if it remained tied to the 1961 Constitution, pushed for deeper and deeper democratisation. In April 1999, a referendum was held to set up a Constituent Assembly, tasked with drafting a new constitution; in July 1999, 131 deputies were elected to the assembly; in December 1999, another referendum was held to ratify the draft constitution; and, finally, in July 2000, a general election was held based on the rules set out in the newly adopted constitution. As I remember, it rained hard on the day that the new constitution was put before the people. Nonetheless, 44% of the electorate turned out to vote in the referendum, with an overwhelming 72% choosing a new start for their country.

Under the new constitution, Venezuela’s old Supreme Court—which the country’s oligarchy had used as a mechanism to prevent any major social changes from taking place—was replaced by the Supreme Tribunal of Justice (Tribunal Supremo de Justicia) or TSJ. Over the course of the past quarter century, the TSJ has been disturbed by several controversies, largely stemming from interventions of the old oligarchy, which refused to accept the major changes that Chávez pushed through in his early years. Indeed, in 2002, the judges on the TSJ acquitted the military leaders who attempted a coup d’état against Chávez, an act which outraged the majority of Venezuelans. This ongoing interference eventually led to the expansion of the bench (as U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt had done in 1937 for similar reasons) as well as more legislative control over the judiciary, as exists in most modern societies (such as in the United States, where Congressional oversight of the courts is institutionalised through instruments such as the ‘exceptions clause’). Nonetheless, this conflict over the TSJ provided an early weapon for Washington and the Venezuelan oligarchy as they attempted to delegitimize the Chávez government.

Jacqueline Hinds (Barbados), The Sacrifice of the Builders of the Panama Canal, 2017.

More people will go to the polls across the world in 2024 than in any previous year. About seventy countries, collectively making up almost half of the world’s adult population, have either already held elections or will hold elections this year. Amongst them are India, Indonesia, Mexico, South Africa, the United States, and Venezuela, which is slated for presidential elections in the second half of this year. Well before the Venezuelan government was expected to declare the date for the elections, the country’s far-right opposition and the U.S. government had already begun to intervene, attempting to delegitimise the elections and destabilise the country with the return of financial and trade sanctions. At the heart of the current dispute is the TSJ, which, on 26 January 2024, refused to overturn a June 2023 decision to disqualify far-right political figure María Corina Machado—who has called for sanctions against her own country and for the United States to intervene militarily against Venezuela—from holding elected office in Venezuela until at least 2029 if not 2036. In the proceedings, the TSJ looked at the case of eight individuals who had been barred from holding public office for a variety of reasons. Six of them have been reinstated, and two of them, including Machado, have had their disqualifications upheld.

The TSJ’s decision evoked fire and brimstone from Washington. Four days after the court decision, U.S. State Department spokesperson Matthew Miller released a press statement that said that the U.S. disapproved of the ‘barring of candidates’ from the presidential elections and would therefore punish Venezuela. The U.S. immediately revoked General Licence 43, a treasury licence that had permitted the Venezuelan public sector gold mining company Minerven to conduct normal commercial transactions with U.S. persons and entities. In addition, U.S. State Department warned that if the Venezuelan government does not allow Machado to run in this year’s election, it will not renew General Licence 44, which allows Venezuela’s oil and gas sector to conduct normal business and is set to expire on 18 April. Later that day, Miller told the press that ‘absent a change in course from the government, we will allow that general license to expire, and our sanctions will snap back into place’.

The United Nations Charter (1945) permits the Security Council to authorise sanctions under chapter VII, article 41. However, it emphasises that these sanctions can only be implemented by way of a UN Security Council resolution. That is why U.S. sanctions on Venezuela, which were first imposed in 2005 and have deepened since 2015, are illegal. As UN special rapporteur on unilateral coercive measures Alena F. Douhan wrote in her 2022 report, these unilateral measures are prone to overcompliance and secondary sanctions as a result of countries’ and firms’ fear of being punished by the U.S. The illegal measures imposed by the U.S. have resulted in tens of billions of dollars of losses since 2015 and have served as collective punishment against the Venezuelan population (forcing over six million of them to leave the country). In 2021, the Venezuelan government formed the Group of Friends in Defence of the UN Charter to bring countries together to defend the integrity of the charter and stand against the use of these kinds of violent, unilateral, and illegal measures. Trade amongst members of this group has been increasing, and many of them (particularly Russia and China) have provided Venezuela with options other than the financial and trade system dominated by the United States and its allies.

Mario Abreu (Venezuela), Mujer vegetal (‘Vegetable Woman’), 1954.

Last month, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research published a landmark study, Hyper-Imperialism, and dossier, The Churning of the Global Order, in which we analysed the Global North’s decline in legitimacy, the new mood in the Global South, and the violent mechanisms used by the Global North to desperately hold onto its power. Last year, the governments of the United States and Venezuela met in Bridgetown, Barbados, under the sponsorship of Mexico and Norway to sign the Barbados Agreement. Under the terms of this agreement, Venezuela would allow the disqualification of some opposition candidates to be challenged in the TSJ and the U.S. would begin to lift its embargo against Venezuela. This was an agreement that the U.S. signed not from a position of strength, but due to the isolation that it faces from the newly buoyant OPEC+ (made up of Global South nations that, in 2022, accounted for 59% of global oil production) and due to its failure to fully assert authority over Saudi Arabia. In an effort to hedge these challenges, the U.S. has sought to bring Venezuelan oil back into the world market. After refusing to participate in the terms set by the Barbados Agreement, Machado challenged her disqualification at the TSJ, whose authority she claimed to honour. But when the verdict went against her, Machado and the United States went into their toolbox and found that all that remained was force: a return to sanctions and a return to the threat of military intervention. Venezuela’s Foreign Minister Yvan Gil called the U.S. reaction ‘neo-colonial interventionism’.

Washington’s return to sanctions comes just as the Associated Press published a report based on a secret 2018 U.S. government memorandum that provides evidence that the U.S. sent spies to Venezuela to target President Nicolás Maduro, his family, and his close allies. ‘We don’t like to say it publicly, but we are, in fact, the police of the world’, former U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency official Wes Tabor told the Associated Press in clear disregard of the operation’s violation of international law. This is the attitude of the United States. That kind of thinking, which calls to mind the clichés of Hollywood Westerns, governs the rhetoric of U.S. high officials. It is in this tone that U.S. Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin threatens militias in Iraq and Syria, saying that while they might ‘have a lot of capability, I have a lot more’. Meanwhile, Austin declares that the U.S. will respond to the strikes on its military base in Jordan ‘when we choose, where we choose, and how we choose’. We will do what we want. That arrogance is the essence of U.S. foreign policy, which calls upon Armageddon when it feels like it. ‘Target Tehran’, says U.S. Senator John Cornyn, unconcerned about the implications of a U.S. bombardment in Iran or anywhere else.

Of course, there is a fine line between persecuting political opponents and disqualifying those who want their country invaded by a foreign power, in this case ‘the police of the world’. It is true that governments often disparage their opponents by alleging that they are agents of a foreign power (as U.S. Senator Nancy Pelosi did recently to those in the United States who are protesting Israel’s genocide against Palestinians, calling them agents of Russia and asking the Federal Bureau of Investigations to monitor them). Machado, however, has openly made statements calling for the United States to invade Venezuela, which in any country would be considered out of bounds.

Of course, there is a fine line between persecuting political opponents and disqualifying those who want their country invaded by a foreign power, in this case ‘the police of the world’. It is true that governments often disparage their opponents by alleging that they are agents of a foreign power (as U.S. Senator Nancy Pelosi did recently to those in the United States who are protesting Israel’s genocide against Palestinians, calling them agents of Russia and asking the Federal Bureau of Investigations to monitor them). Machado, however, has openly made statements calling for the United States to invade Venezuela, which in any country would be considered out of bounds.

In December 2020, I met with a range of opposition leaders in Venezuela who had turned against the regime change positions of people like Machado. Timoteo Zambrano, a leader of Cambiemos Movimiento Ciudadano, told me that it was no longer possible to go before the Venezuelan people and call for an end to Chavismo, the socialist programme set in place by Hugo Chávez. This meant that large sections of the right, including Zambrano’s social democratic formation, have had to acknowledge that this standpoint could not easily win popular support. The far right, comprised of people like Juan Guaidó and María Corina Machado, do not have the stomach for actual democratic processes, preferring instead to ride into Caracas on the backs of an F-35 Lightning II.

Not even a few months after promising sanctions relief to Venezuela, the U.S. has returned to its hyper-imperialist ways. But the world has changed. In 2006, Chávez went to the United Nations and asked the world’s peoples to read Noam Chomsky’s Hegemony or Survival and then mused, ‘Dawn is breaking all over… It is that the world is waking up. It is waking up all over. And people are standing up’. On 31 January 2024, Maduro went to the TSJ headquarters, where he said, ‘We do not depend on gringos or anyone in this world for investment, prosperity, progress, advancement, [or] growth’. Channelling Chávez from eighteen years ago, Maduro said, ‘Another world has already been born’.

Warmly,

Vijay