John Shannon Saul, the writer, scholar, and solidarity activist died in Toronto on September 23, 2023. He leaves behind a rich scholarly and activist legacy, having authored, by a conservative estimate, some 25 books on African history, politics, and society. He was also one of the founders and key figures in the Toronto Committee for the Liberation of Portugal’s African Colonies (TCLPAC) which later became the Toronto Committee for the Liberation of Southern Africa (TCLSAC).

Assessing the full scope of Saul’s work would require, in deference to his own prodigious output, multiple volumes. What I would like to do instead is to trace a key theme in his work, namely his understanding of solidarity as a theory and a practice. Here I rely principally on his wonderful memoir Revolutionary Traveller: Freeze Frames from a Life and conversations we had in 2014 for my forthcoming book on solidarity in the Canadian anti-apartheid movement. His memoirs trace his intellectual and political development from Toronto’s quiet northern suburbs to the frontlines of Africa’s anti-colonial struggles. He is at pains, however, to not centre his own narrative, but rather “to shift the book’s centre of gravity away from the too exclusive focus upon the author and instead onto other actors and situations—onto those, in fact, whom a relationship of solidarity is being established.” Solidarity is an anchoring principle in the text, as indeed it was in John’s life. While he rarely wrote about the topic directly, much of his work was concerned with understanding the particular dynamics of liberation struggles and where actors based elsewhere could intervene most effectively.

Socialism in theory and practice: Tanzania and Mozambique

Saul was a product of the intellectual currents which dominated ‘New Left’ thinking on both sides of the Atlantic in the mid-1960s. He marched against the war in Vietnam, was in Paris during the May 1968 protests, and through his mentors at the University of Toronto and Princeton followed the process of decolonization underway in Africa. This grounding in a humanist strain of Marxism was a compass for much of his later writing, characterized by a skepticism toward Soviet-style Marxism and a theoretical openness to issues of race, gender, and the importance of democratic and open debate—if this makes me a liberal, he once wrote, “then so be it.” For five decades he travelled back and forth between Canada and Southern Africa observing and participating in anti-colonial movements and debating the challenges of post-colonial development. It was through these encounters, or ‘revolutionary travels’ as he calls them, that he developed a theory and practice of solidarity that reflected both his Marxist humanism and his own personal brand of intellectual rigour and discipline—he was not someone who shied away from disagreement. What he termed ‘critical solidarity,’ was an outcome of these long-term engagements with liberation movements, a close study of the political economy of development in Africa, and a sober assessment of the challenges and opportunities for social transformation within and outside of global capitalism.

In 1966 Saul went to Tanzania with the aim of collecting material for a doctoral dissertation. That work was put on hold when he was offered an interim teaching position at the University of Dar es Salaam. Here he collaborated with, among others, Walter Rodney and Giovanni Arrighi on a number of projects some of which are collected in Essays on the Political Economy of Africa. Saul’s tenure in Tanzania coincided with then President Julius Nyerere’s Arusha Declaration, which outlined a pathway toward African socialism and self-reliance. While supportive of Nyerere’s efforts, Saul soon recognized the anti-democratic nature of these declarations from above and criticized the state for its clampdown on strikes and student activism. Saul saw the impact of this directly on his students. In 1970, the Tanzanian army stormed the campus, dragging the leader of the student council through campus at gunpoint. “Slowly but surely,” he wrote, “progressive voices were being stilled… contracts at the university were allowed to lapse.” Nevertheless, Saul recognized that advances could be made even within the contradictions of African socialism. One way was to push for educational reforms.

Among the key debates Saul engaged in during this period was what role the university should play in Tanzanian society. Saul and others drafted a proposal which would see the reorganization of disciplinary departments and the introduction of a series of courses on Tanzanian economy, history, and society. The idea was not to displace the need for necessary technical skills, but rather to supplement technical education with a robust understanding of Tanzanian social and economic history. One of the challenges of the post-colonial project was how to develop a class of technicians and bureaucrats committed to social transformation and not merely their own class mobility. Their aim was not to preach moral values to aspiring bureaucrats, but rather to outline the parameters for a socialist mode of thinking and analysis which could help realize some of the aspirations contained in the Arusha Declaration.

This was not merely a commitment to a more egalitarian educational system, although it certainly contained elements of that, but an understanding of some of the key challenges of socialist development in Africa, namely the emergence of classes and groups with divergent interests and access to benefits. In his work with Giovanni Arrighi he warned that:

After independence, when past education, political record, and current bureaucratic position came to be the chief determinants of privilege in the new society, a rather narrow vested interest in the system and a growing consciousness of a differential positions vis-à-vis the mass became a dominant feature of the new elites.

While some of the key challenges to socialist transformation remained the power of international capital and Cold War threats, Saul insisted that the emergence of a self-indulgent domestic elite would prove to be one of the major challenges for broader social transformation. He would be proven correct over and over. African socialism, he argued, failed to grapple with the realities of national class formation. At the same time, simply replicating Chinese or Soviet models in Africa were doomed to failure. There was a need for dialogue, experimentation with alternatives and a commitment to democracy. In a reflection years later on the Tanzanian experience, Saul recognized the critical “need for democratic guarantees in order to give democratic forms the potential to be real and meaningful for those who need them most.”

Saul’s position did not earn him any favours with the Tanzanian government, and he soon found himself without a job. In 1972, before he returned to Toronto, he was invited by the Mozambican liberation movement FRELIMO (an acronym for the Portuguese name Frente de Libertação Moçambique, or Mozambique Liberation Front) to visit some of the liberated regions in northern Mozambique. Mozambique provided another attempt at constructing socialism in southern Africa, this time from below and very much in the face of intense violent repression by Portugal and the apartheid state. It was here that Saul encountered the potential that movements held for lifting people up through development and education, and, in the process, working to diminish gendered divisions. FRELIMO was not only fighting a guerilla war against Portugal and apartheid-backed forces but trying to build something new and revolutionary. It was different from what he had seen in Tanzania, something more egalitarian and participatory. Yet this attempt at building African socialism too would succumb to a range of pressures, internal and external. The failure of socialism in Mozambique, Saul later reflected, was largely a result of external factors, namely the destabilizing war waged by apartheid South Africa. Nevertheless, FRELIMO’s adoption of vanguardist and authoritarian practices undermined efforts to sustain revolutionary gestures from below.

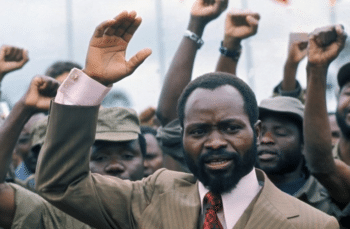

Samora Machel was a prominent African revolutionary and politician who served as the first president of Mozambique from 1975 until his death in 1986. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Before he returned to Toronto, FRELIMO’s leader Samora Machel paid him a visit. The best thing he could do, Machel told him, was to go home and convince his own government to recognize and support anti-colonial struggles. How to act on this advice would be a question that preoccupied Saul for the rest of his life.

Solidarity back home

Back in Toronto, Machel’s words moved Saul to establish the Toronto Coalition for the Liberation of Portugal’s African Colonies (TCLPAC) with other likeminded activists and academics. The return home was challenging. Saul faced a public and political class largely uninterested or openly hostile to African anti-colonial struggles. Canadian policy toward southern Africa was fundamentally dishonest. Public condemnation went unmatched by any trade or diplomatic consequences. Culturally, Saul reflected that most Canadians remained attached to a “set of mythologies, deeply ingrained in culture, and our own stunted sense of what the possibilities for meaningful social change, our own cynicism about the political realm… all of which are underwritten by the pervasive ethos of racism in Canada.” However, the situation in the 1970s was changing rapidly. Armed movements were struggling against the last remnants of European colonialism in Angola and Mozambique, Ian Smith’s white minority regime in Zimbabwe was waging a bush war (the Second Chimurenga) against multiple liberation movements, and the South African apartheid regime intensified its crackdown on political dissent.

The late 1970s also saw a range of movements emerge in solidarity with the so-called Third World. In many cases, these movements were driven by activists who had spent time in these regions, often witnessing the violence of colonialism firsthand and making connections with liberation movements. In the churches, groups like the Taskforce on the Churches and Corporate Responsibility mobilized to withdraw investments from apartheid South Africa. Figures like Jim Kirkwood in the United Church and Dave Beer in Canadian University Service Overseas (CUSO) returned to Canada and pushed their respective organizations to support liberation movements. The question of how best to express solidarity, and with whom, was grist for the mill of political debate during this period. While many openly supported liberation movements like the African National Congress (ANC) and FRELIMO, others hesitated in being openly associated with movements engaged in armed struggle receiving support from the Soviet Union. The Canadian anti-apartheid movement that emerged in this period was far more dispersed than other national solidarity movements. Unlike the British anti-apartheid movement, which was centrally controlled and received direction from the ANC, the Canadian movements was an agglomeration of groups who often expressed support for the ANC but did not receive marching orders from its Toronto office.

As Portuguese colonialism waned and the struggle against apartheid intensified, TCLPAC became the Toronto Committee for the Liberation for Southern Africa’s Colonies (TCLSAC). The version of solidarity that characterized TCLSAC was distinct, often reflecting the New Left tendencies of the group’s members and its suspicion of Soviet-style Marxism. For Saul, the group’s aim was to first expose Canada’s hypocritical stance in Southern Africa. He wrote, at the time:

We were determined not to be tourists in our own country! From the very beginning we began to explore Canada’s far from savoury role and to link Canadians negatively affected by the same companies and by our government’s own shabby and capitalist-defined policies at home.

Solidarity then was not only about looking elsewhere, but very much about looking inward, both at Canada and, as he wrote, “at the deep struggle within ourselves.” In a TCLSAC letter from this time, directed to the ANC’s office in Toronto, the group clarified that its mission was both to support liberation movements while advancing social change in Canada.

It must be stressed that a second important criterion in our choosing campaigns and defining their form and content is how they relate to the goal of social change in Canada. Such campaigns should not contribute to reinforcing status quo values in Canada, nor should Southern Africa be presented as something removed and separate from people’s lives, as a horrific situation about which they should merely be ‘shocked’ or ‘outraged’. Rather, the workings of Canadian society by showing that Southern Africa is connected to peoples’ lives here, and by using Southern African conditions and developments (both oppression and liberation) to challenge the status quo values for Canadians. In this way we contribute to a movement for change in Canada.

The statement reveals TCLSAC’s political groundings in the dependency-theory thinking popular during this period. Underdevelopment was a product of a highly interconnected global capitalism in which the prosperity of countries like Canada rested on the oppression and exploitation of peripheral states. In order to struggle against apartheid in South Africa then, Canadians should act internally against those political and economic actors which allowed it to endure. This thinking was not counter to the position of liberation movements, but it was not of the sloganeering and flag waving variety that some preferred.

In the 1980s the Canadian anti-apartheid movement found its legs, with a series of high-profile conferences attended by hundreds of movement activists, and an increasing willingness on the part of the federal government to implement sanctions against South Africa. Inside South Africa, a range of new actors had emerged to challenge the apartheid state. Some, although by no means all, were connected the exile ANC leadership, but they had emerged and acted largely independently. Even as groups like TCLSAC were willing to acknowledge the role of the ANC as an exile government in waiting, they refused to ignore the dynamism of these independent civil society movements that had emerged inside the country in the 1980s.

We were prepared to say the ANC were leading actors in the struggle, but what is happening on the ground is real. Here I think the phrase ‘direct links stink’ is quite revealing. The idea that you could somehow make a link to people struggling in South Africa, and God knows that there were millions of groups involved on the ground struggling, who weren’t all marching to the tune of the ANC… To make a link with these groups on the ground and then to be told that direct links stink because you didn’t go through the ANC and SACP [South African Communist Party], well that’s partly what it was about. In retrospect, I don’t think we were critical of the ANC enough. I think the ANC was always a player, but never the most important player. And if I had to summarize in very bold language what happened, I think the ANC did enough to retain a certain amount of credibility inside the country, but the real running in the 80s was being made by the unions and by the UDF [United Democratic Front].

The charge of ‘direct links stink’ was thrown at solidarity groups who engaged in solidarity efforts outside official ANC channels. Such a move was often interpreted as disloyalty by liberation movements. For Saul, this openness to political possibilities as they emerged on the ground, and unwillingness to take direction from liberation movements, was a hallmark of what he described as ‘critical solidarity.’

Critical solidarity was saying well the ANC has their own problems, let’s talk about them in a polite way, there are other things happening, and so we’re not going to become party liners for the ANC. We are going to become critical comrades in dialogue with them… We weren’t party-liners, at least I wasn’t, I’d say we were formed by the politics of the New Left at the time. We had a scepticism about possibilities, but a commitment to the hope that something more might be done. And occasionally we let our hope get in the way of our scepticism, but I don’t think there were too many places where our scepticism got in the way of our hope.

The late 1980s witnessed the mainstreaming of the global anti-apartheid movement, making it one of the first truly global civil society movements of the twentieth century. This groundswell arguably shifted the tide against apartheid. And yet Saul and others in TCLSAC wondered whether this embrace of liberation was not a strategy to contain a more revolutionary transformation. Many of the groups that emerged in the 1980s to handle funds provided by the Canadian government to support the anti-apartheid effort were NGOs, and some tempered their calls for sanctions in order to maintain relations with the Canadian government. This ‘domestication’ of the movement, as Saul put it, had a contradictory effect. On the one hand it made the anti-apartheid cause palatable to a broader Canadian public. On the other, it stripped from the movement a more radical core in which the question of socialist transformation was notably absent. The end of apartheid he reflected represented,

a victory over racism no doubt, but a victory that left the urge for liberation unfulfilled on a number of fronts.

Solidarity after liberation

For a solidarity activist who had long supported liberation movements, how to relate to them once in power proved challenging for Saul. In Mozambique, Saul had enjoyed close relations with FRELIMO and worked with them on educational reforms, even as he criticized them for their vanguardism. The South African case was different. He had been supportive of the ANC but remained critical of their top-down politics and their relationship to community movements that had emerged inside the country in the 1980s. After 1994 such criticism was not welcomed, and he was soon branded an ‘ultra-leftist.’ Saul rankled at the accusation not because it expressed a sectarian posturing, but because it reflected a crisis of political imagination among those who levelled it. The language of socialism and structural transformation had disappeared as consultants from the World Bank swept in to advise policymakers. “How,” he wondered,

can one adopt a vantage point true to the undoubted victories of the past, that also enables one to evaluate honestly and critically a less than happy present?

Cover of a 1989 edition of the magazine Southern Africa Report, which Saul edited for many years.

Saul spent the late 1990s and much of the 2000s writing about what he called a ‘false decolonization,’ and, the failure of both nationalist movements and global capitalism to address fundamental development challenges in Africa. In books like The Next Liberation Struggle, he looked both at past liberation struggles, including experiments with socialist development, and toward the future at new historic actors. He drew from his writings on Tanzania and Mozambique to warn of the dangers of national liberation as a tool for the class mobility of a domestic elite, and the constraints that global capitalism placed on any endogenous development model. In the South African case, he was initially hopeful that the ANC’s Reconstruction and Development Program provided some openings to advance structural transformation of the economy. This, however, was short-lived and by 1996 the Growth, Employment and Redistribution program demonstrated the entrenchment of neoliberal policy. Saul was willing to consider the cup of liberation in South Africa half full in the late 1990s, but by the end of the millennium, it seemed to him half empty.

If national liberation movements had failed to bring about any radical outcomes, then what was next? Here Saul was always searching, questioning. “We must explore,” he wrote, “the boundaries of this moment, the threshold of renewal for liberation.” His eye in the 2000s increasingly turned to emerging social movements in South Africa, what he called a “range of resistances to neo-liberal orthodoxy and the bureaucratization of the erstwhile mass democratic movement.” Yet despite this hope, he recognized that these were isolated struggles, often internally divided and without a base to launch mass struggle. He was skeptical of whether these diverse assemblages of movements could cohere into something greater—they lacked ideological orientation and a mass base, but they were embers of something. Drawing from Sam Gindin’s work on structured movements of left forces, he expressed hope that a coalition of movements, not quite a party, could pave the way for the next liberation struggle.

The dialectics of solidarity

Rather than a fixed set of political principles, Saul imagined solidarity as an active process of building and assessing relationships, being open to critique and debates, and, in doing so, producing new political possibilities. In his writings and indeed in his life, solidarity was a travelling concept, informed by the dynamics of struggle in one place and transported elsewhere. It was transnational in its outlook but emphasized the importance of rooting solidarity in certain places. Apartheid and colonialism were not, he insisted, moral problems removed from Canadian reality. Rather, an interconnected global capitalism connected Bay Street to the mines of Johannesburg. Solidarity was both about looking at ourselves and others, and by doing so creating new and potentially liberatory social relations.

Saul’s understanding of solidarity was shaped not only by these revolutionary travels and encounters with liberation movements, but a recognition of the failures of the national liberation project. The question of class formation in postcolonial societies, the relationship between the party and a political base, the role of domestic and international capital, and democracy were constant themes in his later work. One can trace these concerns from his work in Tanzania in the 1960s through his work on South Africa in the 2000s. His method was dialectical, recognizing both the constraints of nationalism and development within the parameters of global capitalism, but always with an eye to spaces of resistance and change within these systems. One senses an acute disappointment in Saul’s later writings about the failure of the national liberation project, but also a profound hope that despite these shortcomings one can always “glimpse something better, something finer, something worth struggling for.”

Chris Webb is a public policy researcher based in Toronto. He is writing a book on the meaning and practice of solidarity in the Canadian anti-apartheid movement.