Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

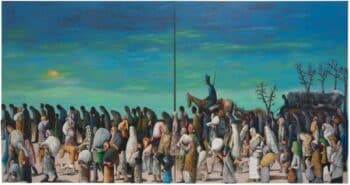

Ala Albaba (Palestine), The Camp #21, 2021.

On 20 February, United States Ambassador to the United Nations (UN) Linda Thomas-Greenfield had the terrible job of vetoing Algeria’s resolution for a ceasefire in Gaza. Amar Bendjama, the Algerian Ambassador to the UN, said that the resolution he tabled had been shaped by conversations amongst the 15 members of the UN Security Council. He was nonetheless asked to delay the resolution, but his country refused. ‘Silence is not a viable option’, he replied. ‘Now it is the time for action and the time for truth’. When the International Court of Justice (ICJ) order on 26 January suggested that Israel’s actions in Gaza amount to a ‘plausible’ genocide, Algeria vowed to take immediate action through the UN Security Council.

Since 7 October, Israel has killed nearly 30,000 Palestinians in Gaza, over 13,000 of them children. Since the ICJ order on 26 January to stop the genocide, Israel has killed over 3,000 Palestinians. After months of fleeing from one alleged safe zone to another that Israel has then bombed, over 1.5 million Palestinians—more than half of the population of Gaza—are now trapped in Rafah, the southernmost point in Gaza and now the most densely populated area in the world. Rafah, which had a population of 275,000 before 7 October, is now being bombed by Israel.

Despite this grim reality, Ambassador Thomas-Greenfield said that the U.S. could not support the ceasefire resolution because it did not condemn Hamas and because it would allegedly jeopardise the ongoing negotiations to release hostages. China’s Ambassador to the UN, Zhang Jun, disagreed, pointing out that the veto ‘is nothing different from giving a green light to the continued slaughter’. Only by ‘extinguishing the fires of war in Gaza’, he said, ‘can we prevent the fires of hell from engulfing the entire region’.

Fuyuko Matsui (Japan), Scattered Deformities in the End, 2007.

Indeed, Thomas-Greenfield’s statement in the UN Security Council came alongside her government’s attempt to provide $14 billion in military aid to Israel. Since 1948, when Israel was created, the United States has provided it with over $300 billion in aid, including an annual disbursement of $4 billion of military aid (and the tens of billions in the pipeline since 7 October 2023). When U.S. President Joe Biden spoke with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on 11 February, instead of criticising the genocide he reaffirmed their ‘shared goal to see Hamas defeated and to ensure the long-term security of Israel and its people’. Thomas-Greenfield’s veto did not come out of nowhere.

The veto has been used in the UN Security Council nearly 300 times. Since 1970, the U.S. has used this power more than any of the other permanent members (China, France, Russia, and the United Kingdom). Many of the US’s vetoes were, first, to defend the apartheid regime in South Africa, which commenced the year Israel was founded, and then to defend Israel against any criticism. For instance, 27 of the 33 vetoes the U.S. has exercised since 1988 have been in defence of Israel’s actions against Palestinians. Since 7 October, the U.S. has vetoed three resolutions in the UN to compel Israel to stop its genocidal bombardment (18 October, 8 December, and 20 February).

Despite its recurrent use by the U.S., the word ‘veto’ does not appear in the UN Charter (1945). However, Article 27(3) of the charter does say that votes in the Security Council ‘shall be made by an affirmative vote of nine members, including the concurring votes of the permanent members’. The idea of the ‘concurring vote’ is interpreted as the ‘right to veto’. For decades, most UN member states have insisted that the UN Security Council is not democratic and that veto power makes it even less credible. No African or Latin American countries have permanent seats on the council, and the country with the world’s largest population—India—is also denied this privilege. The P5 (Permanent Five, as they are called) have not only dominated the Security Council but have also weakened the importance of the UN General Assembly, whose own resolutions have no enforcement power.

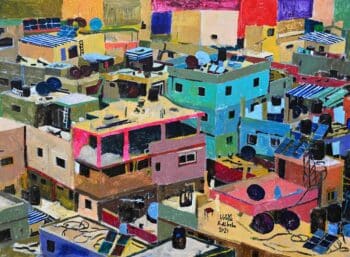

Ana Sophia Tristán (Costa Rica), CO-VIDA, 2020.

In 2005, the UN held a World Summit to assess high-level threats to the world order where Costa Rica’s then Vice President Lineth Saborio Chaverri said that the ‘veto right should be eliminated in matters of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and massive violations of human rights’. After that summit, Costa Rica joined with Jordan, Liechtenstein, Singapore, and Switzerland to create the Small Five (S5) to advocate for the UN Security Council to be reformed. They placed a statement in the General Assembly which specified that ‘no permanent member should cast a veto in the sense of Article 27, paragraph 3, of the charter in the event of genocide, crimes against humanity, and serious violations of international humanitarian law’. But this has had no impact. After the S5 disbanded in 2012, 27 states joined together to create the Accountability, Coherence, and Transparency (ACT) group, largely to reform the ‘right to veto’. In 2015, the ACT group circulated a code of conduct specifically on UN action against serious violations of humanitarian law. By 2022, 123 countries had signed onto this code, though the three countries that have most energetically used the veto in the past few years (China, Russia, and the US) did not. With the increased tensions that the U.S. has imposed on China and Russia, it is unlikely that these two countries—now threatened with attack by the US—will accede to disband the veto.

The UN Charter, the most important treaty on the planet, is an attempt to end war and ensure that every human life is cherished. And yet, our world is fractured by an international division of humanity according to which the lives of some people are worth much more than the lives of others. This division is a violation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and of the basic shared instinct for social equality. Protecting the children of Palestine, for instance, is treated with much less urgency than protecting the children of Ukraine (as NBC News London correspondent Kelly Cobiella said, Ukranians are not refugees from just anywhere: ‘To put it bluntly… These are Christians; they’re white’.) This international division of humanity creeps into public consciousness generation after generation.

In The Book of Embraces (1992), our friend Eduardo Galeano wrote a short fragment on the grave divisions that afflict our world and drive a cold, iron stake into the heart of our sense of humanity. That fragment is called ‘The Nobodies’:

Fleas dream of buying themselves a dog, and nobodies dream of escaping poverty: that one magical day good luck will suddenly rain down on them, that it will rain down in buckets. But good luck doesn’t rain down yesterday, today, tomorrow, or ever. Good luck doesn’t even fall in a fine drizzle, no matter how hard the nobodies summon it, even if their left hand is tickling, or if they begin the new day with their right foot, or if they start the new year with a change of brooms.

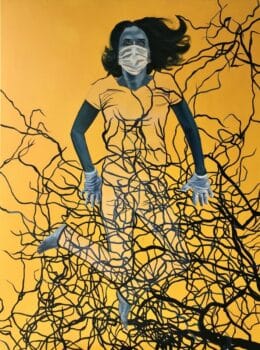

Benny Andrews (USA), Trail of Tears, 2005.

The nobodies: nobody’s children, owners of nothing. The nobodies: the no ones, the nobodied, running like rabbits, dying through life, screwed every which way.

Who are not, but could be.

Who don’t speak languages, but dialects.

Who don’t have religions, but superstitions.

Who don’t create art, but handicrafts.

Who don’t have culture, but folklore.

Who are not human beings, but human resources.

Who do not have faces, but arms.

Who do not have names, but numbers.

Who do not appear in the history of the world, but in the police blotter of the local paper.

The nobodies, who are not worth the bullet that kills them.

Warmly,

Vijay