Private equity firms are buying up the U.S. economy and stripping it for parts. From healthcare to education, utilities, and more, massive firms like Blackstone and the Carlyle Group have acquired vast holdings across critical industries essential to the health and well-being of everyday people. Instead of seeking to make these ventures more profitable, private equity firms are more likely to orchestrate to bleed their assets for short-term gains—even if those assets are univerisites, hospitals, or nursing homes. Gretchen Morgens0n, author of These Are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs—and Wrecks—America, returns to The Chris Hedges Report to discuss how private equity came to hold America hostage. This is the second part of an earlier interview, you can watch the first part here.

Studio Production: Cameron Granadino, Adam Coley

Post-Production: Adam Coley

TRANSCRIPT

Chris Hedges: The U.S. economy is being held hostage by a small cohort of financiers who run private equity firms. Apollo, Blackstone, the Carlyle Group, Kohlberg, Kravis, Roberts; These equity firms buy up and plunder businesses, piling on debt, refusing to reinvest, slashing staff, and often driving companies into bankruptcy. The object is not to sustain businesses but to harvest them for assets to make a short-term profit. Those who run these firms such as Leon Black, Henry Kravis, Stephen Schwarzman, and David Rubenstein have amassed personal fortunes in the billions of dollars.

The wreckage they orchestrate is taken out on workers who lose jobs, see salaries and benefits slashed, are taken out on pension funds that are depleted because of usurious fees, or are abolished. And on our health and safety, residents of nursing homes, for example, owned by private equity firms, experience 10% more deaths because of staffing shortages and reduced compliance with standards of care.

Private equity owns hospitals and has created a health crisis. Nursing shortages have contributed to one of every four unexpected hospital deaths or injuries caused by errors. The private equity firms do not serve patients but profits. They have closed hospitals, especially in rural America, and they cut back on stockpiles of vital medical devices including ventilators and personal protective equipment. In 1975, the U.S. had about 1.5 million hospital beds and a population of about 216 million people. Now, with a population of over 330 million people, we have around 925,000 beds. 56% of Americans have medical debt, even though many have insurance, and 23% owe $10,000 or more.

Emergency room visits and emergency rooms, often run by private equity firms, contributed to medical debt for 44% of Americans. At the same time, the healthcare system—Because of this slash-and-burn assault—Was unprepared to handle the COVID epidemic, seeing 330,000 Americans die during the pandemic because they could not afford to go to a doctor on time. These private equity firms, like an invasive species, are ubiquitous. They have acquired educational institutions, utility companies, and retail chains while bleeding taxpayers hundreds of billions in subsidies made possible by bought-and-paid-for prosecutors, politicians, and regulators.

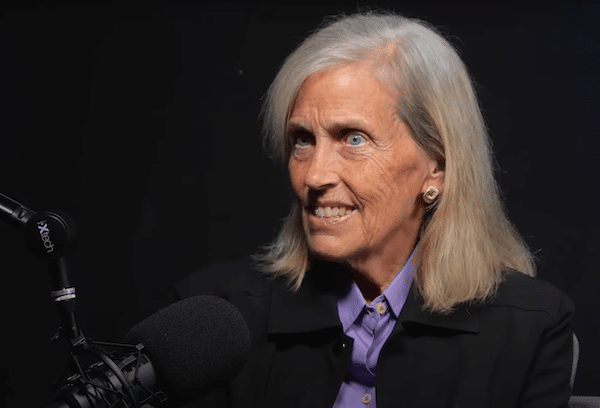

Joining me to discuss private equity firms and their assault on the economy is the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, GM, who—Along with Joshua Rosner—Wrote, These are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs and Wrecks America. Let’s begin with what they are. They’ve just rebranded themselves, but I’ll let you start.

Gretchen Morgenson: Well, Chris, these are the old takeover titans that we started to learn about in the ’80s, RJR Nabisco was the big deal that focused everyone’s attention on them. They just rebranded themselves into something called private equity. A little bit genteel, sounds like it might be fair—equity being that word. So these are those corporate raiders that were fearsome, and Congress, at that time, was concerned about what they were going to do to the economy. Congress lost interest and went on to the next thing, and they did then go on to—Over the next few decades—Pillage the economy and workers and pensions, as you pointed out.

CH: Explain how they work. Because it’s all about debt. And what’s interesting from your book, is they don’t put very much money in. But I’ll let you explain the mechanics of it.

GM: Okay. These firms, first of all, raise money for their buyouts. They don’t use a lot of their own money for those buyouts. What they do is they go to public pensions, they go to endowments, they go to the big institutional investors and say, we’re putting together a fund, we’re going to buy-out companies, we’re going to make them more efficient, and then we’re going to sell them in 5-7 years at a profit, and you will be able to reap those gains along with us. But yes, the private equity titans do not put a lot of their own money at stake here. 1%-2% of these funds are typically the private equity firm’s money. So after they have raised the money, they go out and look for companies to buy, and they home-in on companies that have assets they can strip.

CH: These are often physical assets that they can sell.

GM: Physical assets like real estate. Now, you pointed out that they’ve taken over a lot of retailers. When that was going on, often they would be buying retailers that had either very, very favorable leases or had land underneath their stores that they could then sell at a profit, stripping the company. It’s not about operating the company, as you say, it’s about stripping the assets, extracting the money that they can from it. It’s an extraction business.

So they buy a company, they then find out how they can make it more efficient, which means, usually, firing many people, stripping the assets, selling them off, and sometimes they sell the assets and they get all their money back—Initially, very, very early on in the process—And what’s left is a carcass. What’s left is a company that has now got an enormous amount of debt piled on top of it.

These transactions are funded by debt, but it’s not the private equity firm that takes on the debt, it’s the company they’re buying. So if they buy a retailer, they’ll put a load of debt on that retailer. Suddenly that retailer has way higher costs of operating, which means that then they have to cut costs elsewhere: fire people, and deplete pensions. It’s a game where a very narrow slice of people win and a huge circle of pain of losers is involved. Everybody else is on the losing end.

CH: Well, because it’s about short-term profit. You have an example in the book about a nursing home system—This was an amazing story. What they did is they sold the physical buildings that had the nursing homes, and then suddenly these nursing homes had to rent, I think it was $40,000 or something more a month. I’ll let you explain. So they’re not just loading it up with debt but also carrying out policies that physically destroy corporations or businesses before they arrive—You have the story of Samsonite, we’ll talk about the steel mill you write about—That we’re healthy.

GM: Absolutely. So the nursing home company that you were talking about, Manor Care, was very well run. The reason that the acquisition was made—And this was Carlyle Group, which is one of the top private equity firms —

CH: Let me interrupt because as you point out in the book, like James Baker, they pull in heavyweight political figures once they’re out of office to run these groups.

GM: Unlike the other firms which are located in New York and are the Wall Street type folks, Carlyle is based in Washington and it’s much more politically astute and there’s a revolving door with government officials; Very high-powered government officials. Anyway, they bought Manor Care. It was a very well-established, well-run, national nursing home company. They immediately sold the land under the nursing homes and made the nursing homes pay rent.

They took out the equivalent of what they had put into the company. They received that when they sold the land. So they were free and clear. Everything after that became gravy for them, so they weren’t concerned about the profits; They were already in the money, as they say. But the nursing homes suddenly had to pay exorbitant rents and that meant that something else had to give.

Ultimately, what ended up happening was an enormous Medicare fraud that was designed to overcharge Medicare for services to these residents, and the stories are absolutely gut-wrenching. There were some whistleblowers who came forward talking about what they were seeing and the DOJ took the case, but then blew the case. But some of the tales that these whistleblowers told about forcing aged, frail, ill residents to go through an incredible rehabilitation that they didn’t need, in order to bill Medicare for these processes, was shocking.

CH: You write about the ER. What are they called? Surprise bills? I can’t remember the term you use. They will hospitalize people who don’t need it. It’s all about money. And then the care is substandard because the staffing is cut.

GM: That’s right. That’s right. So ultimately, Manor Care was driven into bankruptcy by the people who bought it, but they didn’t lose because they had done this transaction to buy the land underneath all of the nursing homes.

CH: You call these private equity firms—These are your words—“Money-spinning machines.” Before we go into specifics, talk about it. Because the amounts are staggering. Maybe we can talk about the charming, is it Leon Black? These people are bringing in these figures—Billions upon billions of dollars. Talk about the amount of money they’re generating.

GM: The net worths of the people running these companies are in the tens of billions. In the COVID years, Steve Schwarzman… He is the head of Blackstone. His net worth doubled during COVID, I think it went up to something like $35 billion or something. Anyway, these companies extract enormous fees for their operation. They extract fees from the pension funds that invest with them.

CH: I want to interrupt you. The deal is they get the pension funds to invest because supposedly the pension funds will make a profit. But then as you write in the book, they force the pension funds to pay them management fees. You have cases in the book where they’re not even doing anything, but if I remember, they’re pulling like 10%, a lot of money. And these pension funds, in the end, don’t make a profit.

GM: Many times they don’t, sometimes they do. The rule of thumb is called “2 and 20.” So they’ll get 2% of the assets under management as a management fee every year, and then 20% of the gains that they make. So this has translated into a billionaire-making machine for these guys that run these firms. And yes, it’s staggering when you pull back the curtain on some of their practices.

One of them that’s outrageous is when they buy a company, they will often install people on the board of the company to watch over it to make sure that they’re going in the right direction. For them anyway, not for the company, necessarily. And they will charge them fees over a period of time for their management expertise. These fees are generally contracted on a 10-year life, but many of these deals they end up selling between 5-7 years.

That’s the goal, as you pointed out, the short-term nature of this. But the company has to pay for the full 10 years of the fees that the private equity firm is charging them. And that’s money for doing nothing. That’s just one of the tricks of the trade that they do to generate billions of dollars for themselves while they’re impoverishing so many other people.

CH: You write that they operate in secrecy with hidden ties to companies they control. The wreckage they leave behind is often difficult to track back to its origins. And I want to raise another point that you do in the book and I thought it was important: Many Americans who are being assaulted this way, know something’s wrong, but they don’t quite know what is wrong. It’s tied to this, almost invisible, hand. Explain that. And then I want you to talk about their political clout because it’s significant. They get the tax breaks, they corrupt the system enough to essentially grease the skids for them to continue to operate.

GM: Absolutely. Absolutely. So the secrecy is important. One of the reasons that we wanted to write this book is to let people know how pervasive this business model is.

CH: Well, you write at one point that all of us, although we don’t know it, are engaging with private equity firms. So talk about how extensive it is and then talk about that secrecy too.

GM: I write in the book, that the coffee and donut that you pick up on the way to work, the child care entity where you drop your son or daughter off, the nursing home where your mother or father lives, it is cradle to grave. You’re impacted by private equity but you don’t know it because these are companies that are buying and selling, but you don’t know who the real owner is behind the scenes. And they like it that way, they want to keep it that way because they operate best in secrecy. They’re private companies. They don’t have to make filings to the Securities and Exchange Commission so a lot of their business and a lot of their practices are hidden from view, and that is by design.

One of the things that could improve our perception or educate people about how pervasive private equity has become is to force these firms to identify themselves as the owners; So it should be the Carlyle nursing home or the Blackstone donut shop or whatever. Just so you are aware of who you are dealing with and whose pocket you’re putting your money into. Now, the secrecy is one thing, the political clout is immense. They have so much money, their tax treatment is an outrage, and many presidents have tried to change it, but have not been able to do so.

CH: Explain the tax part.

GM: Their fortunes are enhanced by the fact that they pay a fraction of what you and I pay on our incomes every year because it’s called carried interest; It’s not considered ordinary income. The ordinary income tax rate is what, up to 35%? What these people pay is around 21% of the income that they receive from their operations. That’s something that’s been in the books for decades but it has created a skewed system where they make fortunes, billions of dollars. The government loses because they’re not generating the tax revenues that they should on those billions. It’s nuts. Now, the last time someone tried to change this, Kyrsten Sinema was a holdout, the —

CH: Because it was good for the people of Arizona.

GM: —Lawmaker from Arizona. She received $1.5 million from the private equity world to stand up and say no, and she scotched it. So getting them to pay their fair share of taxes would be a good thing. It would help the government, it would generate more income, and it would take away this unfair aspect of their business.

CH: You write, “Routinely lionized in the financial press for their dealmaking and lauded for their ‘charitable’ giving, these unbridled capitalists have mounted expensive lobbying campaigns to ensure continued enrichment from favorable tax laws. Hefty donations have won them positions of power on museum boards and think tanks. They’ve published books on leadership extolling ‘the importance of humility and humanity’ at the top while eviscerating those at the bottom. Their companies arrange for them to avoid paying taxes on the billions in gains that their stockholdings generate. And, of course, they rarely mention that the companies they own are among the largest beneficiaries of government investments in highways, railroads, and primary education, reaping massive perks from subsidies and tax policies that allow them to pay substantially lower rates on their earnings.

These men are America’s modern-age robber barons. But unlike many of their predecessors in the 19th century, who amassed stupefying riches by extracting a young nation’s natural resources, today’s barons mine their wealth from the poor and middle class through complex financial dealings.” These people not just control politicians, but they serve in government. You have several examples of that. So explain a little bit about how they dominate the political system.

GM: Jay Powell, our head of the Federal Reserve Board, was a Carlyle executive. They’re everywhere. Again, it’s this pervasiveness. But even if they’re not on the job, say, in the government, they are behind the scenes manipulating outcomes so that their businesses will benefit. They’re so powerful and so wealthy. And you know, Chris, better than anybody, how money is so central, unfortunately, to how our government works. You have not had enough attention to this wealth grab by these people.

The one thing we did have, the activity, the practices were so outrageous that it got Congress to act, and that was on the surprise medical bills that you mentioned a bit ago. This was a creation, the brainchild of a company called Envision, which is owned by KKR. And what Envision did was it went into emergency departments and started running many of those emergency departments in a hospital. It wouldn’t own the hospital, but it ran the emergency departments.

Envision decided that what they could do is they could make the emergency department a separate entity outside of the insurance coverage that the hospital’s patients would normally have. So you’re in your town, you go to the emergency department, you’ve broken your arm or whatever, your insurance—Which covers your normal hospital stay or treatment—You naturally assume it’s going to cover your emergency department bill.

Well, Envision carved themselves out of that so that you would have to pay more. And this was something that was so crazy and impossible to think could happen, that Congress did something about it and changed and curbed the practice. They didn’t eliminate them, but they curbed it. And guess what? Envision went bankrupt after that because its business model required them … Its business model was based on ripping people off.

CH: I want to talk about several cases, including that heartbreaking case of the girl and woman who needs constant medical care, but people have to get the book. Let’s talk about, in detail, Noranda Aluminum.

GM: Noranda was a company that had a very profitable, very, very well-located aluminum smelter on the banks of the Mississippi River in the Bootheel region of Missouri. Not a wealthy part of the country, but this was a company, was a smelter aluminum production that had 2,500 jobs. Well-paying jobs, good benefits, healthcare, and the company had been there for many, many years. And this was a well-established smelter doing a tremendous business on the Mississippi. They could deliver their aluminum all up and down the country. Great company. Apollo comes in and buys it. And they promise —

CH: Let me interrupt you.

GM: —Yes.

CH: When a private equity firm like Apollo comes in to buy it, it’s not always the case that the company’s looking to sell. Is that correct?

GM: Well, the company has to be willing to sell.

CH: But aren’t they able to pressure companies to sell against their will or not?

GM: Well, it depends. Usually, it’s about money. So if it’s a public company that has publicly traded shares and the shareholders are the ones who will then make the decision about whether the acquisition is made, generally what happens is that the shareholders say, great, I’m going to get a windfall. I’m going to get whatever premium to whatever the stock price was trading at when the acquirer comes in and says, I’ll pay you $10 more a share. Generally speaking, the shareholders say, yay. Let’s do it. Let’s do the deal.

When it’s a private company, you’re then talking about persuading whoever owns it that they are better off taking the money and running. But it’s almost always a premium they’re paying and that gets people’s attention and the owners or the shareholders say yes. So Apollo comes in, they buy the smelter, they promise that they’re going to do right by the 2,500 families whose workers are there, and they immediately load it up with debt. This was a company that did not have a lot of debt, so it didn’t have enormous interest costs. It didn’t have to pay those costs.

CH: I want to ask… When they load it up with debt, did they say, okay, these are our assets, and put the assets… That’s how they can get the debt because they’re putting the assets up as collateral?

GM: Correct. So the asset is this smelter and this huge infrastructure. And they also had a very low cost of electricity.

CH: Just to interrupt again, is that debt used to pay for the acquisition?

GM: Yes.

CH: Yes.

GM: The debt is used to pay for the acquisition, but it again allows the private equity firm to take the money out. They’re loading the debt onto the company itself, not onto the private equity firm. So the company is the one that now has to struggle with the debt costs, the increased interest expense that’s associated with the debt. So Noranda, they load it up with debt. Almost immediately Apollo gets its money out. All of its money is out.

CH: Which it wasn’t that much.

GM: Wasn’t that much. Maybe six months or something like that. They were able to extract all their money by putting the debt on the company. So now Noranda is struggling under this debt load. Apollo then raises more debt, they ultimately make three times their money on the Noranda purchase. Meanwhile, the company starts to struggle. Not surprisingly.

CH: It goes under because it has to service the debt now.

GM: It starts to struggle because it has to service the debt. So then Apollo says, wow, this is a problem. We need to negotiate with the state of Missouri’s utility commission to lower our electricity costs or otherwise, we’re going to leave. We’re going to sell the company, take it somewhere else or something. So they negotiate with the utility commission a lower rate, even though it means that the other ratepayers in Missouri have to pick up the slack and have to cover that difference.

Apollo gets the lower rate, it then starts to fire people because it can’t make ends meet. The company is struggling again, the debt is too high, and there may have been an economic downturn. Aluminum wasn’t quite as in demand but it was the debt that was causing the problems. The company ultimately goes bankrupt, but Apollo has made three times its money. So people are thrown out of work. They savaged three different pensions. The Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation had to come in and bail out three Noranda pensions because of the bankruptcy.

They had ratepayers paying more across the state. Noranda was the biggest taxpayer in this small town in Missouri all of a sudden, the tax base crumbled, and the school teachers had to pay their own healthcare costs. What Noranda owed for the school payments, for its taxes, was not paid because they went bankrupt. So this was a perfect example of the circle of pain that these people create when they make all of the money for themselves. Three times their investment but they harmed ratepayers, they harmed school teachers and school children, they harmed workers, and they harmed pensioners. That’s what we’re talking about.

CH: You write, “To outsiders, the buyout firms appeared to be fierce rivals competing assiduously to beat each other out for the companies they hope to acquire. In reality, the firms were cozy collaborators, members of a club that meant richer profits for them and fewer for everyday investors.” Explain how that works.

GM: This was an amazing case. It was brought by shareholders or maybe debt holders; I think it was shareholders. But anyway, they turned up some amazing documents in the discovery where they had emails between these big powerful firms that everyone thought were competing to buy companies, KKR, et cetera. The emails showed them to be very chummy. They would say, oh, well, we’ll stand back on this deal. We won’t do this deal. We’ll let you take this deal. You give us the next one.

So it became clear when you have this kind of acquisition, if you have more bidders—If you have two bidders, three bidders, five bidders—The people who own the company who are selling it are going to get a better price because those bidders are going to bid up the price of the company. If you only have one bidder, they’re not competing with anyone else and they’re not going to be raising the cost of the acquisition. So what happened was the shareholders ended up getting less because the other firms had decided not to compete and not to bid up the price.

It was collusion that people had not understood was happening on a regular basis, and it was shocking. They ended up paying a lot of money to settle the case. But it was a real eye-opener about how they are working together to make sure that they don’t have to pay too high a price and that there won’t be tough competition.

CH: Isn’t that illegal? Sorry to be so naive.

GM: DOJ didn’t think so.

CH: Oh, really?

GM: Did not bring a case.

CH: Okay. I want to talk about utilities. I wrote a book called America the Farewell Tour, it opens in Scranton, Pennsylvania, which had declared bankruptcy, and they were stripping city parking, sewers, and anything they could sell off, which made things worse. It was a temporary fix but rates skyrocketed. You write about Bayonne; Talk about how they’re cannibalizing basic services that were once managed by cities, communities, and the government.

GM: You remember the idea that took hold in the ’80s about privatization; That the government doesn’t know how to run anything and we should privatize all of these organizations and services. The private sector knows what they’re doing and they’re going to do a better job—We know that that’s not the case, but in any case, these private equity firms do understand that there is money to be made buying into these kinds of utilities that are necessities. We are not talking about frivolous items, we’re talking about water.

So Bayonne, New Jersey, like many cities in the Northeast, had a decrepit water system. Pipes were bursting and needed help. Along comes KKR and they say, we’ll help you out. We’ll buy this, we’ll give the money to you that you need to refurbish. Let’s make that happen. They did the deal, you can well imagine that the people on the KKR side of the table were pretty shrewd operators, and the people on the water utility side of the table were probably not as shrewd.

What ended up happening was that for the people of Bayonne, New Jersey, which is a working-class town, not a wealthy town, their water rates skyrocketed. And again, it was a situation where this very small group of financiers wind up winning, gaining enormous amounts, and everyone else winds up paying the freight.

CH: When you write “skyrocketed”… A 2021 report by the Association of Environmental Authorities, a public utility nonprofit, said “The average annual bill for privately-owned water systems in the U.S. was 60% higher than that of publicly-owned systems. And in privatized arrangements, low-income households spent 1.55% more of their income on water.” So these rate hikes are staggering. They’re very, very high and crippling.

GM: Crippling. Crippling. And it’s not like you can say, okay, well, let’s not drink any water today. Let’s not use water to cook our food, wash our clothes, or do our dishes. It’s not a frivolous item.

CH: Let’s talk about the social cost. We’ve talked in a microcosm, but what’s it doing to the national economy? How is it affecting us globally?

GM: The first thing, and the most important 30,000-foot view, is it expands the wealth gap in this country, it blows that out. So people who are in the lower echelon, the disparity between the rich and poor in this country, is not healthy. It’s unsustainable.

CH: Is it unsustainable because in essence, they’re cannibalizing everything?

GM: Well, it is unsustainable because you can’t keep extracting money from the middle class and poor people to become billionaires; That’s a recipe for disaster. Capitalism is supposed to, in theory, benefit a wide array of people. It’s supposed to provide prosperity for people to enhance their economic situation. Have a good job. Be able to —

CH: But when it’s regulated.

GM: —When it’s regulated. Right.

CH: When it’s not regulated… You have a term in the book, “a-hole capitalism.”

GM: Right. Right. Me, me, me. Right? I, me, mine, capitalism. Where I don’t care about everyone else. It’s all about what I want and what I can get for myself. So it’s the wealth gap in this country that has blown out and I believe these entities are contributing mightily to that. Then, when you get lower down, that’s the 30,000-foot view. When you get lower down, you have these situations where people are personally affected by this.

Whether it’s because the tax base in their town disappears because a company goes bankrupt—That means the taxpayers have to make up the difference—Whether you’re talking about a nursing home where people die more frequently, whether you’re talking about pensions that are depleted because of this, meaning your retirement is going to be less prosperous than you had hoped it would be; These are the stories that you don’t hear about Chris, and that’s why this is important to know.

All the business press lionizing these people and talking about their deals and how they’re this billion and that billion, you never hear about the people on the other side of the transaction. And that’s wrong because there are people on the other side of the transaction and their stories and their voices are important.

CH: Well, that’s been the great failing. The failing of the presses, that we’re not telling those stories. Reading your book and seeing that line you have in the book about how people know something is wrong, but they don’t know what exactly is wrong, I read that as a huge factor in the rise of a figure like Trump. I don’t know how you feel.

GM: Yes, I agree 100%. They don’t understand finance. And yes, the financiers make it complex for a reason. They hide behind the complexity. They hide behind the secrecy. They hide behind the fact that you don’t know that they own the companies. I’m not blaming people for not understanding it, not knowing what the problem is, because it is hidden from view and they do that on purpose.

But it is pernicious and it is impacting people. It’s causing job losses, it’s causing reduced pensions, it’s causing increased costs for taxpayers, which all contribute to this sense of unease about my future. Am I going to have enough money to retire? Am I going to have enough money to send my child to college? There’s an unease going on that these people are contributing to.

CH: You make a point in the book with the surprise bills from the emergency room. The average, if I remember it, was about $600 or something. Well, since they don’t know these bills are coming, these families living on the edge are completely wiped out. This has catastrophic effects and these predatory practices are bleeding, especially with the working, poor, and the lower working class, which you make very clear in the book.

And that has political consequences when it’s not addressed. And it’s largely not addressed because under our system of legalized bribery, in essence, these people own the political class. Not only own the political class but—Especially during the Trump administration—A lot of these private equity people were in the administration.

GM: Steve Schwarzman was at Trump’s right hand in many photographs. He was his business advisor. Financial expert.

CH: One crook advising another. Great. All right, thanks. That was Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, GM, author of These Are The Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs and Wrecks America. I want to thank The Real News Network and its production team, Cameron Granadino, Adam Coley, David Hebden, and Kayla Rivara. You can find me at chrishedges.substack.com.