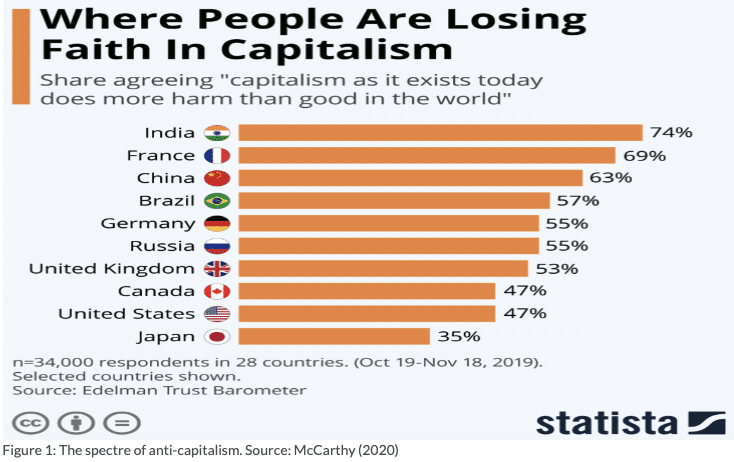

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ Communist Manifesto was published in February, 1848. It is truly a part of what Marx called world literature that capitalism has given rise to. The Manifesto is a call to revolutionary action. It is important to return to the text now when a large number of people around the world support the idea of socialism and are critical of capitalism. Interests in anti-capitalism and socialism are indeed growing in many parts of the world. According to a poll conducted in 28 countries, including the United States, France, China and Russia, 56% agree that capitalism “is doing more harm than good in its current form” (McCarthy, 2020; see Figure 1).

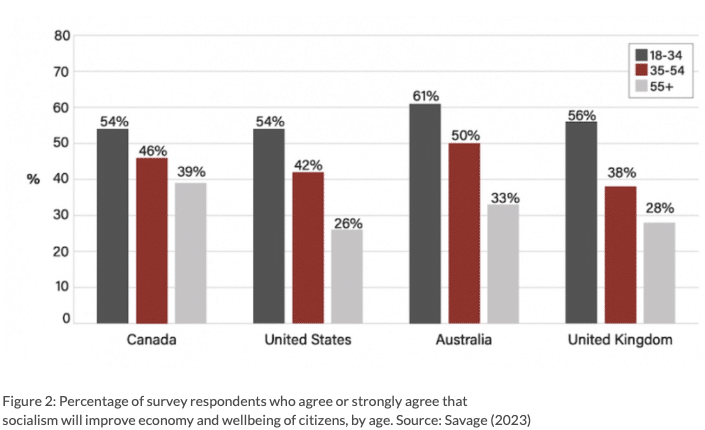

According to another poll, conducted in Canada, the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom in 2022, the idea of socialism finds a warm reception in all these countries (Savage 2023, Figure 2). In particular, the majority of younger people (18-34 years of age) prefer some form of socialism.

This survey reveals that despite decades of anti-socialist propaganda:

the word ‘socialism’ still maintains a positive connotation with big pluralities in major English-speaking countries and remains strongly associated with both social services and economic redistribution. Quality social programs, the redistribution of wealth, and public services provided by the state and financed through progressive taxation all remain popular propositions (Savage, 2023).

The growing number of people who favour socialism forms the basis for a movement to win over more people to the idea of socialism and away from the propaganda that naturalizes a system dominated by capitalist market relations. But many of those who have a favourable view of socialism may not adequately understand what it is and how to get there or they may not exactly know how/why capitalism is the cause of their misery. A socialist movement requires ideas that not only defend socialism but also show how capitalism works and why it is harmful to the majority. Many of these ideas are present in The Communist Manifesto written by Marx and Engels almost 175 years ago, in a context where people were turning to revolutionary ideas and practices in Europe, and which provides some of those ideas.

The Manifesto depicts capitalist society as one that immensely develops humanity’s productive forces but unable to meet common people’s needs as it is a competitive, crisis-prone, exploitative, and unequal society. It says that the working class immensely suffers under capitalism due to primary exploitation in the workplace and secondary exploitation outside, but that it is not only a suffering class but also a fighting class, the struggle of which capitalism unwittingly enables (through the development of big cities and means of communication), although it also impedes workers’ struggle (for example, through competition for jobs in the capitalist labour market). This article discusses some of the main intellectual and political lessons of the Manifesto for our time, and especially, for the newly-radicalizing youth.

A historical-materialist world outlook

The Manifesto’s implicit social theory (historical materialism) represents an application of Marx and Engels’ materialist dialectics. This is indicated by Engels himself who says in his 1883 Preface to the German edition of Manifesto:

The basic thought running through the Manifesto … [is] that economic production, and the structure of society of every historical epoch necessarily arising therefrom, constitute the foundation for the political and intellectual history of that epoch; that consequently (ever since the dissolution of the primaeval communal ownership of land) all history has been a history of class struggles, of struggles between exploited and exploiting, between dominated and dominating classes at various stages of social evolution….1

As Leon Trotsky (1937) comments:

The materialist conception of history, discovered by Marx only a short while before and applied with consummate skill in the Manifesto, has completely withstood the test of events and the blows of hostile criticism… All other interpretations of the historical process have lost all scientific meaning.

The intellectual and political importance of the Manifesto is such that:

It is impossible in our time to be not only a revolutionary militant but even a literate observer in politics without assimilating the materialist interpretation of history. (ibid.)

Today we live in a time (a post-truth time) where under right-wing attacks on rational thought, people are giving up on ideas that are based on reason and evidence (Das, 2023a). Alongside right-wing people, there are others (postmodernists, for example) who seek to explain the world purely in terms of ideas and beliefs and in a way that is generally anti-science. The materialist conception of history of the Manifesto is the best antidote to these tendencies.

Class approach to society

The Manifesto takes a class approach to society: society is to be seen in terms of the exploiting and exploited classes that constitute it.2 Marx is critical of all those who talk about human beings “in general”. He therefore rejects the idea that it is possible to “appeal to society at large, without the distinction of class” (Marx and Engels, 1948: 32).3 He would reject the idea that climate change has been caused by humanity as such. Recently, the UN Secretary-General António Guterres said, “Humanity is in the hot seat [and] humans are to blame.” This is the wrong approach. To say that climate change has been caused by humanity as such is to imply that climate change mitigation must be on everyone’s shoulders. Marx would reject that class-blind approach to climate change. He would instead say that climate change is mainly due to the big business class of advanced capitalist nations and that they must be primarily responsible for cleaning up the environment. As Bryan Dyne (2023) notes: “‘Humanity’ is not to blame; capitalism is.”4 In fact the failure to mitigate climate change can be explained partly by Marx’s characterization of the capitalist system as a sorcerer: “Modern bourgeois society, … a society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange, is like the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells” (p.17). Climate change is a product of capitalism, and its mitigation is in the interest of capitalism, but it is unable to control climate change.

The Manifesto’s class approach to society would also reject an identity politics view of society so dominant in academia and media today. In this view, the main division in society is not between classes but between races, religious groups, castes, genders, etc. (Das, 2020).

Marx’s emphasis on class struggle also counters the tendencies in academia and the labour movement that seek to revise Marxism “in the spirit of class collaboration and class conciliation” (Trotsky, 1937). In relation to major global issues such as climate change and rise of fascistic forces, whether in India or the U.S., many advocate what is effectively a popular front approach where the exploited masses are supposed to be in an alliance with progressive sections of the capitalist class to fight these problems. The Manifesto would instead remind us of the futility of denying the class struggle approach. It would say that the working class must mobilize itself independently of all fractions of the bourgeoisie–democratic or not, green or not, imperialist or not, conciliatory or not, lesser evil or not.

Capitalist society’s contradiction

Marx applies historical materialism to shed critical light on capitalism. The Manifesto’s analysis of the main characteristics of capitalist society is perhaps more true now than when it was written: wage-workers are paid a wage for its bare maintenance as wage-workers and nothing more; a large part of the net product they produce is appropriated by the capitalists for free (exploitation in the workplace); exploitation of people by traders, money-lenders, etc.; competition as the basic law of motion of capitalism; the gradual impoverishment of the rural peasantry and urban small-scale owners; the extreme concentration of wealth in the hands of an ever-diminishing number of capitalists and landowners and the numerical growth of the wage-dependent men, women and children (proletarians); globalization of capitalism; and the tendency of capitalism to lower the living standards of the workers, and even to transform them into paupers maintained by government or private charity.5

Marx discusses capitalism’s permanent crisis-proneness (although he had not quite theorized the reasons for it as he eventually did in Capital Vol 3). While many people think of capitalism as more or less a smooth process, except for business cycles, etc., Marx’s characterization of capitalism as “a deeply contradictory process is rather more convincing than capitalist triumphalism” (Wood, 1998). Marx says:

Modern bourgeois society … a society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange, is like the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells. For many a decade past the history of industry and commerce is but the history of the revolt of modern productive forces against modern conditions of production, against the property relations that are the conditions for the existence of the bourgeois and of its rule (p.17).6

This means that even if good days come at times (for example, income can rise if total investment rises without a sharp rise in the organic composition of capital), they will be temporary.

While Marx correctly emphasizes the class approach to society, and sheds light on positive and negative impacts of capitalism, he tends to overestimate capitalism’s ability to eliminate the intermediate layers between capital and labour and thus to proletarianize petty traders and peasants, etc.

[T]he elemental forces of competition have far from completed this simultaneously progressive and barbarous work. Capitalism has ruined the petty bourgeoisie at a much faster rate than it has proletarianized it. Furthermore, the bourgeois state has long directed its conscious policy toward the artificial maintenance of petty-bourgeois strata. At the opposite pole, the growth of technology and the rationalization of large-scale industry engenders chronic unemployment and obstructs the proletarianization of the petty bourgeoisie. (Trotsky, 1937).7

Class struggle and revolution

Many academics and trade union leaders are always eager to emphasize agency in the form of trade union economic struggle. For Marx, however, workers’ class struggle is a political struggle, with the aim of conquering state power: “The organization of the proletariat as a class [is] consequently its organization into a political party” (p. 19). The ruling class is unfit to rule as it cannot meet the needs of the masses, so there must be a “forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions” to create a society where capitalist private property is abolished and the state, as long as it is necessary, is under the democratic control of the masses, and where the abolition of class oppression will also negate the need for national oppression. Mere trade union action will not lead to socialist revolution. Trade unionists and anarcho-syndicalists forget this. Marx anticipated Lenin’s distinction between trade unionist politics, or bourgeois politics, of workers and class struggle proper.

The Manifesto says that communists “openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions.” This means that the proletariat cannot conquer power within the legal framework established by the bourgeoisie nor by slowly transforming the capitalist state into a socialist state, nor only by trade union action. This is the case whether or not there is liberal democracy or whether or not the communist movement is strong or not. The bourgeoisie will not give up power peacefully. It itself did not win power from the feudal ruling class peacefully.

Marx talks of the necessity for “the proletariat organised as the ruling class”: this is nothing but the dictatorship, or the political hegemony, of the proletariat to replace the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. “At the same time it is the only true proletarian democracy” (Trotsky, 1937).8

Marx says that: “Though not in substance, yet in form, the struggle of the proletariat with the bourgeoisie is at first a national struggle” (p. 20). However, “The international development of capitalism has predetermined the international character of the proletarian revolution.” (Trotsky, 1937). “United action, of the leading civilised countries at least, is one of the first conditions for the emancipation of the proletariat” (p. 25).

The subsequent development of capitalism has so closely knit all sections of our planet, both developed and less developed, that the problem of the socialist revolution has completely and decisively assumed a world character (Trotsky, 1937).

In emphasizing class struggle, Marx is a true Marxist as per Lenin’s (1918:25) definition:

Only he is a Marxist who extends the recognition of the class struggle to the recognition of the dictatorship [political hegemony] of the proletariat. That is what constitutes the most profound distinction between the Marxist and the ordinary petty (as well as big) bourgeois.

Marx not only emphasizes class struggle but the highest form of class struggle, revolution and conquest of state power. And given the possibility of nuclear annihilation and global warming roasting us to death, proletarian revolution is an urgent task. The idea of the necessity for revolution goes right against the reformist ideas of academic Marxism. Consider David Harvey:

the kind of fantasy that you might have had—socialists, or communists, and so on, might have had back in 1850, which is that well, okay, we can destroy this capitalist system and we can build something entirely different—that is an impossibility right now. We have to keep the circulation of capital in motion, we have to keep things moving…(italics added).

For Harvey, Capital’s “call to the barricades of revolution” is merely “the rhetoric of the Communist Manifesto” (2010: 301). If this is Marxism, Marx is not one.

The dominant role of the proletariat

In emphasizing class struggle, Marx is absolutely clear about the dominant role of the proletariat. Marx insists that the main agent to fight for communism is the proletariat. Non-proletarian suffering masses cannot be truly revolutionary:

The lower middle class, the small manufacturer, the shopkeeper, the artisan, the peasant, all these fight against the bourgeoisie, to save from extinction their existence as fractions of the middle class. They are therefore not revolutionary … for they try to roll back the wheel of history (p.20).

Of course, this does not mean that workers can overthrow capitalism on their own. They need the support of non-proletarian masses–the small-scale non-exploiting producers. This means that, among other things, the topic of alliance between workers and petty producers, and especially the peasantry, requires much more urgent attention than Marx gave in the Manifesto (see Das, 2023b on this topic).

There can be no substitute for the proletarian leadership of the revolution against capitalism. And it is the proletariat as such and not this or that section of the proletariat that some modern day Marxists talk about—e.g. Third World proletariat, low-caste or Black proletariat, environmental proletariat, etc. This is in contrast to many academic Marxists, including Harvey, who do not accept the leadership of the proletariat in the fight against capitalism. Harvey (2010), for example, argues for “a broader notion of an alliance of forces in which the conventional proletariat is an important element, but not necessarily . . .a leadership role.”

Marxist left unity

In some cases, Marx says, communists may have to fight along with less revolutionary forces. But if they do, “they never cease … to instill into the working class the clearest possible recognition of the hostile antagonism between bourgeoisie and proletariat” (p. 34). So, while communists are the most radical, they reject sectarianism. This advice is prescient given the extreme disunity among Marxists and communists in the world today. Communists “have no interests separate and apart from those of the proletariat as a whole”, nor do they “set up any sectarian principles of their own, by which to shape and mould the proletarian movement” (p. 22). Marx would reject the approach of many communist groups who look at the world from the standpoint of their own political programmes only (Das, 2019).

Lumpenproletariat and fascism

The proletariat as a whole, which has nothing but its labour power, when armed with class consciousness, is the revolutionary class. Yet, sections of the dispossessed class can be reactionary. Marx says that while exploitation prompts class struggle, the outcome of class struggle, including in its revolutionary form, is not fixed: it could result in a new and better society or a common ruin of contending classes or barbarism. He further says that elements of the lumpenproletariat can be bribed tools of the capitalist class.9 These points have implications for our time. A form of barbarism is the action of the fascistic forces, whether in India or the U.S. or Europe.

If capitalists as a class fail to meet the social-ecological needs of the masses, and if the masses are unable to eliminate capitalism, fascism arrives.10 And, in this context, what Marx calls the lumpen elements (these people are hardly employed and part of the lowest layers of society) do indeed serve as “a bribed tool of reactionary intrigue” (p. 20). Today they serve as moral police, forcing people to conform to conservative social values (they are against inter-faith relations and the principle of equal rights of women, for example) or as informal police humiliating and hurting minorities (or immigrants) and serving as foot soldiers of right-wing pro-corporate and majoritarian governments such as in India (as well as many parts of Europe and the US). Aijaz Ahmad (Ahmad, 2013:20) says about lumpen proletarians:

the life of the lumpenproletariat is by its nature one that creates no community out of any shared conditions of labour but must always work within collectivities that are tentative, transitional and forever in need of getting re-invented out of the emergencies that individuals in this quasi-class face all the time. Bereft of class belonging, they are prone to temptations of community-belonging to caste, religion or whatever—a kind of belonging far more abstract than the concrete belonging to a community of labour (ibid).

The lumpenproletariat’s lack of productivity, their lack of a sense of who they are, robs them of self-pride; and “that pride must somehow be regained, even if it is by harming others, be it by way of crime or by that purported non-crime that is communalism [religious sectarianism] itself, with all its violences” (ibid.).

Marx’s point about non-capitalist oppressed elements serving a reactionary role for the capitalist class can be extended to the petty bourgeoisie. Trotsky (1937) said that in a period of capitalist crisis, “to maintain its unstable rule” financial capital “can do nothing but turn the petty bourgeoisie ruined and demoralized by it into the pogrom army of fascism.” Indeed, and to paraphrase Trotsky, the mass of pauperized petty bourgeoisie and lumpenproletariat and other similar sections befuddle themselves “with fairy tales concerning the special superiorities” of certain religions or races. Racial, religious or ethnic supremacism is the ideological raw material of fascism.

The right-wing parrots “nation” and “national”. Let it tremble at Marx’s view of the nation: “Since the proletariat must … rise to be the leading class of the nation, must constitute itself the nation, it is so far, itself national, though not in the bourgeois sense of the word.” (p.25). On the other hand, it is also true that “The working men have no country, no fatherland or motherland” (ibid.). This means that the proletarians must not support the capitalist class of “their” country against the capitalist class of another country in predatory wars.

The capitalist state

Many people see the state as class-neutral or as having a lot of autonomy from the capitalists. Marx instead says that: “The executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie” (p. 15). This has been proven true in spite of attempts in academia, especially, of western liberal democracies, to emphasize the so-called relative autonomy of the state and in spite of the masses’ unreasoning trust in the state. The state and capitalist class are two arms of the same body: capitalist class relation (Das, 2022a). The idea that the state is the executive committee of the bourgeoisie is true whether or not people choose their leaders through elections. “The democracy fashioned by the bourgeoisie is not … an empty sack which one can undisturbedly fill with any kind of class content. Bourgeois democracy can serve only the bourgeoisie…. Whenever this ‘committee’ manages affairs poorly, the bourgeoisie dismisses it with a boot” (Trotsky, 1937).

Many have argued that the state has a much-diminished role under neoliberalism and globalization. Here as well the executive committee theory of Marx does well: “Contrary to much conventional wisdom today, ‘globalization’ has made the state not less but more important to capital. Capital needs the state to maintain the conditions of accumulation and ‘competitiveness’ in various ways” (Wood, 1998).11 “‘Neoliberalism’ is not just a withdrawal of the state from social provision. It is a set of active policies, a new form of state intervention designed to enhance capitalist profitability in an integrated global market” (ibid.). “As neoliberal states step up their attacks on social provision and adopt austerity measures to enhance ‘flexibility,’ the complicity between the state and ‘globalized’ capital is becoming increasingly transparent” (Wood, 1998). Because the state is constantly needed by capital and it is increasingly clear to at least class-conscious people that the state is not neutral, the state becomes a target of class struggle.

Capital’s need for the state makes the state again an important and concentrated focus for class struggle. And the fact that the state is visibly implicated in class exploitation has consequences for class organization and consciousness. It may help to overcome the fragmentation of the working class and create a new unity against a common enemy. It may also help to turn class struggle into political struggle. (Wood, 1998).

The socialist transitional state

Following the overthrow of the capitalist state, a socialist state will come into existence for a transitional period but its traits will be fundamentally different. Marx says that “Political power, properly so called, is merely the organised power of one class for oppressing another” (p. 27). When class relations disappear the conditions for such public power, for the state, also disappear:

If the proletariat during its contest with the bourgeoisie is compelled, by the force of circumstances, to organise itself as a class, if, by means of a revolution, it makes itself the ruling class, and, as such, sweeps away by force the old conditions of production, then it will, along with these conditions, have swept away the conditions for the existence of class antagonisms and of classes generally, and will thereby have abolished its own supremacy as a class (ibid).

Indeed, “When, in the course of development, class distinctions have disappeared, and all production has been concentrated in the hands of a vast association of the whole nation, the public power will lose its political character” (ibid.). This implies that socialism cannot be conflated with state-ownership of means of production. Initially, the state owns the means of production but ultimately, it is the common people–a vast association of the whole nation–that controls these.

Conversely, if following a socialist revolution, there is a monstrous growth of state coercion as under Josef Stalin, that proves that “society is moving away from socialism” (Trotsky, 1937). Just as some material improvement of workers under capitalism does not negate the existence of capitalism, similarly, the fact that masses experience some material improvement after a post-capitalist revolution does not mean there is socialism. Socialism means socialist democracy (for the masses, the majority).

Was the 1917 revolution a wrong idea?

Written during a period of political upheaval, the Manifesto overestimates prospects for socialist revolution, and indeed “underestimated the durability of capitalism and how long it could keep on expanding” (Wood, 1998). Based on our experience of the 20th century, we must be mindful of the fact that “The protracted crisis of the international revolution, which is turning more and more into a crisis of human culture, is reducible in its essentials to the crisis of revolutionary leadership” (Trotsky, 1937). Marx overlooks the role of reformist leaders, bourgeois ideology, identity politics, economic differentiation among workers, etc. and tends to overestimate the revolutionary maturity of the working class.

The Manifesto is undoubtedly a call for revolution against capitalism. But given the experience of the 1917 revolution, many have raised doubts about Marx’s theory of revolution. For some, the failure of 1917 proves Marx correct. For example, Ellen Wood (Wood, 1998) says:

we should not underestimate the significance of his [Marx’s] assumption that a socialist revolution would be most likely to succeed in the context of a more advanced capitalism. In that sense, it could be argued that the ultimate failure of the Russian Revolution, which occurred in the absence of those preconditions, fulfilled his predictions all too well.

So, implicitly, 1917 had to fail and the Bolsheviks led by Lenin and his followers were wrong. I disagree. The correlation between social relations and productive forces is not a matter of national scale. The failure of 1917 is primarily because of the failure of revolution in advanced countries and consequent strangulation of the 1917 revolution through imperialist military threats and the capitalist law of value.

The 1917 experience has taught us that communism cannot be established in a single country, poor or rich, given the global character of capitalist production and exchange (and finance). This was Lenin and Trotsky’s point. “The Bonapartist degeneration of the Soviet state is an overwhelming illustration of the falseness of the theory of socialism in one country.” (Trotsky, 1937).

The 1917 experience has also taught us that even some aspects of socialism, however distorted, and some regulation of the law of value, however weak, can, within limits, develop productive forces quickly and meet people’s needs better than capitalism, at comparable levels of economic development. As well, it is because of the threat of the 1917 revolution spreading to the West that workers’ struggle in the West was able to win some concessions from the ruling class in the form of the welfare state. The 1917 experience also contributed to decolonization.

The Global South and imperialism

The Manifesto is relatively deficient with respect to what is now called the Global South and yet its methodology can allow one to extend its lessons for the South. First of all, Marx’s point that “The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionising the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society” (p. 21) has limited relevance to large swathes of the South where labour productivity is extremely low and where anti-diluvian social relations or relations of formal or hybrid subsumption of labour–and not social relations of advanced capitalist production backed by systemic tendency towards technical change–tend to be extremely strong. How do we explain under-development? The key is in Marx’s point that capitalism has made less developed nations dependent on the more developed ones, “nations of peasants on nations of bourgeois, the East on the West” (p.17).

Secondly, as Trotsky rightly complains, ‘the Manifesto contains no reference to the struggle of colonial and semicolonial countries for independence … the colonial question was resolved automatically for them, not in consequence of an independent movement of oppressed nationalities but in consequence of the victory of the proletariat in the metropolitan centers of capitalism.” The questions of revolutionary strategy in [imperialized nations], that are “not touched upon at all by the Manifesto … demand an independent solution”. Nationalism in imperialist nations and nationalism in the South are not the same. The South continues to exist under imperialist domination, if not under formal colonialism, even if the native capitalist class has become much more powerful since decolonization. The importance of anti-imperialist struggle, to be led by the proletariat, cannot be over-emphasized. Marx would not disagree.

Thirdly, the Manifesto’s relevance to the South partly stems from the fact that it was written when capitalism was not well advanced in any of the European countries, and they all had predominantly rural populations, like large parts of the Global South now. Yet, even while advocating the abolition of property in land, and emphasizing the key role of the proletariat as the revolutionary agent, Marx does not deal with the specificity of the Global South where many property-owners appropriate surplus in ways that are not exactly capitalist or where many direct producers are not wage-wage earners. In this context, the land question–agrarian revolution–is very important. In the South, given the bourgeoisie is linked to the landlord class and given that “it is scared that any struggle against non-capitalist exploiters might spill over to be an anti-capitalist struggle, the bourgeoisie will not support any struggle to eliminate the feudal remnants, so the land question and any pre-capitalist sources of oppression can be eliminated only by a proletarian government that comes on the back of the communist revolution” (Das, 2022b:242). Agrarian revolution is only possible under proletarian rule.

As evidenced by the entire subsequent course of development in Europe and Asia, the bourgeois revolution, taken by itself, can no more in general be consummated. A complete purge of feudal rubbish from society is conceivable only on the condition that the proletariat, freed from the influence of bourgeois parties, can take its stand at the head of the peasantry and establish its revolutionary dictatorship. By this token, the bourgeois revolution becomes interlaced with the first stage of the socialist revolution, subsequently to dissolve in the latter. The national revolution therewith becomes a link of the world revolution. The transformation of the economic foundation and of all social relations assumes a permanent (uninterrupted) character. (Trotsky, 1937).

Indeed:

For revolutionary parties in backward countries of Asia, Latin America, and Africa, a clear understanding of the organic connection between the democratic revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat–and thereby, the international socialist revolution–is a life-and-death question (Trotsky, 1937).

The Global South, which is dominantly capitalist, experiences not only remnants of semi-feudal rubbish in specific localities but also imperialist exploitation and subjugation.

Capitalist development has been inseparable from imperialisms of various kinds, from traditional forms of colonial exploitation to the current burden of debt in the third world, or the exploitation of cheap third world labor by today’s ‘transnational’ companies. The contradiction between capitalism’s productive capacity and the quality of life is manifest today in the growing polarization between an opulent North and an indigent South. But the same contradiction is evident within the advanced capitalist economies themselves. (Wood, 1998).

Similarly, the on-going fascistic attacks on democracy and secularism, which cannot occur without the support of the capitalist class, can only be successfully fought by the proletariat leaning on small-scale producers as a part of its fight for socialist democracy. So too the endless predatory wars and proxy wars and genocide supported or prompted by imperialist powers, as well as the damaging control of international institutions such as World Bank and IMF on the South.

It is useful to be reminded of Marx’s point that “The Communists everywhere support every revolutionary movement against the existing social and political order of things.” This implies that “The movement of the colored races against their imperialist oppressors is one of the most important and powerful movements against the existing order and therefore calls for the complete, unconditional, and unlimited support on the part of the proletariat of the white race” (Trotsky, 1937). This principle also applies to the struggle of oppressed religious groups (whether they be Muslims or Hindus or Jews or Christians), oppressed castes, oppressed genders and oppressed nationalities including those that are experiencing genocide (as in Palestine).

Conclusion

The capitalist ruling class is unfit to rule. Capitalism must go. There is no alternative but socialism. If it does not go, there is the real possibility of social-ecological barbarism. Capitalism will go only when it is overthrown by the proletariat. There is no other way. The proletariat is the only force that can overthrow capitalism by leading small scale producers and oppressed masses. There is no other class to be the leader of the revolution. The proletarian revolutionary struggle must include struggle for reforms as a part of revolutionary struggle. Socialism/communism is more than egalitarianism or a few pro-worker policies. The fight for socialism requires more than the fight for reforms. It requires a political party of the proletariat that is class conscious. The Manifesto, when properly understood, can play a key role in promoting proletarian class consciousness. It is a key ammunition in building a movement for global socialist democracy, a society of free association of direct producers.

Raju J Das is a Professor at York University. Email: [email protected]. Website: https://euc.yorku.ca/faculty-profile/das-raju-j/. His most recent books include: Marx’s Capital, Capitalism and Limits to the State: Theoretical Considerations. London: Routledge. This article draws on Das (2022b).

References

Ahmad, A. 2013. ‘Communalisms: Changing Forms and Fortunes’. The Marxist, XXIX 2, April—June 2013

Das, R. 2023a. Contradictions of Capitalist Society and Culture: Dialectics of Love and Lying. Leiden/Boston: Brill.

Das, R. 2023b. ‘On the worker-peasant alliance in India (and other countries of the Global South)’. LINKS: International Journal of Socialist Renewal; https://links.org.au/worker-peasant-alliance-india-and-other-countries-global-south

Das, R. 2022a. Marx’s Capital, Capitalism and Limits to the State: Theoretical Considerations. London: Routledge.

Das, R. 2022b. ‘On the communist manifesto: ideas for the newly radicalizing public’. World Review of Political Economy, 13(2), 209—244. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48687800

Das, R. 2020. ‘Social Oppression, Class Relation, and Capitalist Accumulation’, In Marx Matters, edited by D. Fasenfest. Leiden: Brill.

Das, R. 2019. ‘Politics of Marx as Non-sectarian Revolutionary Class Politics: An Interpretation in the Context of the 20th and 21st Centuries’, Class, Race and Corporate Power, 7(1).

Dyne, B. 2023. ‘The climate crisis reaches a tipping point’. wsws.org. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2023/07/29/bnlm-j29.html

Harvey, D. 2010. ‘Explaining the crisis’. ISR: International Socialist Review. https://isreview.org/ issue/73/explaining-crisis

Lenin, V. 1918. The state and revolution. https://www.marxists.org/ebooks/lenin/state-and-revolution.pdf

Marx, K., and F. Engels. 1848. The Communist Manifesto. Marxists.org. https://www.marxists.org/ archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Manifesto.pdf

McCarthy, N. 2020. ‘Where People Are Losing Faith In Capitalism’. Statista. https://www.statista.com/chart/20600/capitalism-as-it-exists-today-does-more-harm-than-good/

Savage, L. 2023. ‘Even Right-Wing Think Tanks Are Finding High Support for Socialism’. Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2023/03/socialism-right-wing-think-tank-polling-support-anti-capitalism

Schmunk, R. 2023. ‘As cost of living soars, millions of Canadians are turning to food banks’. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/food-bank-use-highest-in-canadian-history-hunger-count-2023-report-1.7006464

Trotsky, L. 1937. ‘Ninety Years of the Communist Manifesto’. https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1937/10/90manifesto.htm

Wood, E. 1998. ‘The Communist Manifesto After 150 Years’. Monthly Review. https://monthlyreview.org/1998/05/01/the-communist-manifesto-after-150-years/

Notes:

- ↩ Engels also says that ‘this basic thought belongs solely and exclusively to Marx’.

- ↩ The relations between classes are objective and antagonistic as they involve a) differential control over property (a minority controls property and the majority do not) and b) exploitation of the property-less (or property-poor) by the propertied. Capitalism is a form of class society.

- ↩ //www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Manifesto.pdf

- ↩ ‘What really blocks every effort to seriously address the climate crisis is the profit system, the subordination of economic life to private profit and the division of the world into rival nation-states’ (ibid.).

- ↩ Consider the Indian government having to provide free food grain to 800 million people. Consider also increasing reliance on foodbanks in Canada. According to one report, ‘nearly two million people–including more employed people than ever–used food banks March 2023 alone. That’s a 32 per cent increase from the same month last year and more than 78 per cent higher than in March 2019’ (Schmunk, 2023).

- ↩ It is enough to mention the commercial crises that by their periodic return put the existence of the entire bourgeois society on trial, each time more threateningly. In these crises, a great part not only of the existing products, but also of the previously created productive forces, are periodically destroyed. In these crises, there breaks out an epidemic …— the epidemic of overproduction’. (p. 17).

- ↩ Concurrently, the development of capitalism has accelerated in the extreme the growth of legions of technicians, administrators, commercial employees, in short, the so-called “new middle class.” …However, the artificial preservation of antiquated petty-bourgeois strata in no way mitigates the social contradictions, but, on the contrary, invests them with a special malignancy, and together with the permanent army of the unemployed constitutes the most malevolent expression of the decay of capitalism. (Trotsky, 1937).

- ↩ ‘Its scope and depth depend upon concrete historical conditions. The greater the number of states that take the path of the socialist revolution, the freer and more flexible forms will the dictatorship assume, the broader and more deepgoing will be workers’ democracy’ (Trotsky, 1937). ‘For the socialist transformation of society, the working class must concentrate in its hands such power as can smash each and every political obstacle barring the road to the new system’ (ibid.).

- ↩ ‘The “dangerous class”, [lumpenproletariat] the social scum, that passively rotting mass thrown off by the lowest layers of the old society, may, here and there, be swept into the movement by a proletarian revolution; its conditions of life, however, prepare it far more for the part of a bribed tool of reactionary intrigue’ (p.22).

- ↩ ‘If the proletariat…proves incapable of overthrowing with an audacious blow the outlived bourgeois order, then finance capital in the struggle to maintain its unstable rule [turns to] fascism’. (Trotsky, 1937).

- ↩ These include ‘direct subsidies at tax-payers’ expense; to preserve labor discipline and social order in the face of austerity and “flexibility” to enhance the mobility of capital while blocking the mobility of labor; to administer huge rescue operations for capitalist economies in crisis (yesterday Mexico, today the “Asian tigers”)—operations often organized by international agencies but always paid for by national taxes and enforced by national governments. Even the imperialism of the major capitalist states requires the collaboration of subordinate states to act as transmission belts and agents of enforcement’ (Wood, 1998).