Part II: Al-Aqsa Flood, or People’s War in the New Era

Mao Zedong says: the enemy advances, we retreat; the enemy camps, we harass; the enemy tires, we attack; the enemy retreats, we pursue. His theorizing on guerrilla warfare can be described as the flea war.

The conundrum of “how would a nation that is not industrial win over an industrial nation” was solved by Mao. Engels saw that nations that are able to provide capital are more likely to defeat [their] enemies. Meaning that economic power has the final word in battles because it provides the capital to manufacture arms. Mao’s solution however was to emphasize non-physical (or non-material) elements. Powerful states with powerful armies often focus on material power; arms, administrative issues, the military, but according to Katzenbach, Mao emphasized time, space (ground), and the will. What that means is to avoid large battles leaving ground in favor of time (trading space/ground with time) using time to build up will, that is the essence of asymmetrical war and guerrilla war.

— Basel al-Araj, “Live Like a Porcupine, Fight Like a Flea” (2018)

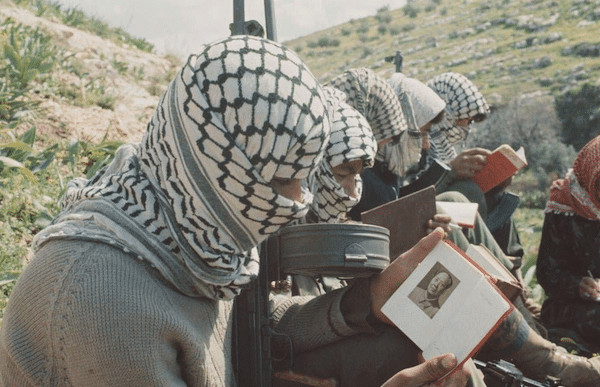

Notwithstanding Mao’s admonition to his PLO visitors to avoid book worship—including and especially of his own works—his writings on guerrilla warfare had by then become canon, and for good reason. Xinhua News Agency reported that the theoretical syllabus for Palestinian guerrillas training in China included “Problems of Strategy in China’s Revolutionary War” (on the 1927-36 phase of the civil war between the CPC and KMT) and “Problems of Strategy in Guerrilla War Against Japan” (on the CPC’s need to maintain guerrilla tactics even in an anti-Japanese United Front with the KMT).

Even as the ideological coordinates of the Palestinian armed struggle moved away from the left-nationalism and Marxism of the 1960s-70s and in a more Islamist direction, the precepts of people’s war retained a timeless quality. Time and again they were taken up (sometimes piecemeal) and creatively adapted to suit contemporary conditions, as in the above passage from polymathic revolutionary intellectual and martyr Basel al-Araj. The current conjuncture in the wake of Operation Al-Aqsa Flood is no different—five months at the time of writing into Israel’s genocidal assault on the people of Gaza, which has slaughtered well over 30,000 martyrs but left the resistance and its fighting capacity stubbornly and miraculously intact.

In this section we aim not to provide a detailed military assessment of the Gaza war and its broader regional repercussions, for which we are eminently unqualified, but to explore some of its key dimensions through the lens of Mao’s writings on guerrilla war. We take as our point of departure the analysis of our comrades in the Palestinian Youth Movement (PYM), who characterize Gaza as simultaneously (and perhaps at first glance paradoxically):

- An open-air prison or concentration camp, already subject to near-genocidal siege conditions prior to October 7 and now converted into a mass death camp;

- The foremost popular cradle of the Palestinian revolution, i.e. “the organ, the beating heart, by which Palestinian resistance is carried out against the Zionist enemy”;

- The “only liberated Palestinian territory” and viable base area for large-scale resistance operations, starting with Israel’s 2005 “disengagement”;

- And the focal point of the regional Axis of Resistance.

Given the unspeakable horrors transmitted daily from Gaza’s killing fields, the first characterization now utterly dominates mainstream conceptions of the enclave. But Palestinians more than anyone else—even and especially those suffering directly under this murderous onslaught—are adamant that it not be allowed to monopolize our understanding of Gaza’s place at the heart of the struggle. To that end we now consider each of the others in turn.

Gaza as popular cradle

Many people think it impossible for guerrillas to exist for long in the enemy’s rear. Such a belief reveals [a] lack of comprehension of the relationship that should exist between the people and the troops. The former may be likened to water, the latter to the fish who inhabit it. How may it be said that these two cannot exist together? It is only undisciplined troops who make the people their enemies and who, like the fish out of its native element, cannot live.

— Mao Zedong, Chapter 6 of “On Guerrilla Warfare” (1937)

Mao first posed this famous metaphor with guerrilla fighters as his audience, in a context where (especially during the civil war) they frequently had to contend with anti-communist ideological conditioning and mass suspicion of all armed formations as “bandits.” While the comparison with the Palestinian armed resistance is inexact, its deep level of implantation within the fabric of society for over 75 years is by no means an automatic byproduct of Zionist oppression. It requires careful and intentional cultivation, and in this sense we can think of the popular cradle as a complementary doctrine for the masses themselves: on how to act collectively as the “water” within which the guerrillas swim.

The Palestinian Youth Movement defines the concept thusly: “The Popular Cradle works as the organ of our struggle by conceptualising resistance as both a normal and necessary state of being and creating a resistance-enabling environment in which the popular masses financially, socially, and politically sustain the resistance and readily accepts the consequences of supporting armed struggle against Zionist settler colonialism.” Historical instances of the popular cradle in action include the widespread adoption by civilian men of the now-ubiquitous keffiyeh, over the then-customary Ottoman-style fez, in order to help armed revolutionaries blend into crowds during the Great Revolt of 1936-39. A more recent example in the same spirit occurred in 2022, when hundreds of men in the West Bank refugee camp of Shuafat shaved their heads in order to thwart Israeli efforts to apprehend or kill the bald resistance fighter Udai Tamimi.

In their analysis PYM considers the entirety of the Gaza Strip to constitute a single, massive popular cradle for the resistance—at a qualitatively larger scale than is practicable in the territorially-fragmented West Bank under the collaborationist Palestinian Authority. As Max Ajl writes, the extraordinary heroism and sumud (steadfastness) of Gazan civilians under Israel’s genocide vindicates this judgment resoundingly:

the popular cradle brings the word resistance beyond armed men to doctors going to their deaths in lieu of abandoning their patients and women and men in the Gaza Strip’s North—facing white phosphorus rather than abandoning their homes. It is precisely the strength of the civilian commitment to the national project that provokes U.S.-Israeli extermination… to break Hamas by breaking its cradle.

Another, more quantitative measure of the popular cradle’s endurance can be derived from public surveys of Palestinians before and after October 7. Of course even in “ideal” conditions, to say nothing of those currently endured by Palestinians in both Gaza and the West Bank, such polls have major limitations as meaningful barometers of mass sentiment. Nor do their results necessarily reflect the dialectical process through which the masses form a collective political subject in the course of true people’s war. With all these caveats, however, it is undeniable that Al-Aqsa Flood catalyzed a qualitative upsurge in the popular embrace of armed resistance. Two months into the war, the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research recorded a doubling of support for Hamas (from 22% to 43%) and a dramatic increase in support for armed struggle generally (from 41% to 63%) compared with surveys before October 7.

This remarkable outcome strongly recalls Amílcar Cabral’s trenchant observation that in Guinea-Bissau’s unfavorably flat physical terrain—a problem even more acute for Palestinian guerrillas—“the people are our mountains.” Returning to the Chinese example, the triumphs and travails of the resistance since October 7 also evoke Edgar Snow’s moving summation of the Long March in Red Star Over China:

In one sense this mass migration was the biggest armed propaganda tour in history. The Reds passed through provinces populated by more than 200,000,000 people… Millions of the poor had now seen the Red Army and heard it speak, and were no longer afraid of it… Many thousands dropped out on the long and heartbreaking march, but thousands of others—farmers, apprentices, slaves, deserters from the Kuomintang ranks, workers, all the disinherited—joined in and filled the ranks.

Gaza as liberated territory

The problem of establishment of bases is of particular importance. This is so because this war is a cruel and protracted struggle. The lost territories can be restored only by a strategical counter-attack and this we cannot carry out until the enemy is well into China. Consequently, some part of our country–or, indeed, most of it–may be captured by the enemy and become his rear area. It is our task to develop intensive guerrilla warfare over this vast area and convert the enemy’s rear into an additional front. Thus the enemy will never be able to stop fighting. In order to subdue the occupied territory, the enemy will have to become increasingly severe and oppressive. A guerrilla base may be defined as an area, strategically located, in which the guerrillas can carry out their duties of training, self-preservation and development. Ability to fight a war without a rear area is a fundamental characteristic of guerrilla action, but this does not mean that guerrillas can exist and function over a long period of time without the development of base areas.

— Mao Zedong, Chapter 8 of “On Guerrilla Warfare” (1937)

The aforementioned Long March was in many ways the paradigmatic example of the conception of strategic depth that Mao articulates here. In that grueling ordeal the Communists maximally exploited the sheer vastness of China’s territory, as they would do again after Japan’s invasion. On the other hand the applicability of this passage to a besieged coastal enclave just 25 miles long and five miles wide, with one of the highest population densities on earth, may not be immediately obvious. But if we examine the long arc of Palestinian struggle at multiple spatial and temporal scales, this principle indeed comes into operation time and again.

It could be argued that up until the First Intifada erupted in Gaza’s Jabalia refugee camp in 1987, Palestinian guerrillas faced the opposite conundrum from that spelled out by Mao. That is to say, after the successive blows of 1948 and 1967 the entirety of historic Palestine came under Zionist occupation, with virtually all Palestinians therein under nearly undifferentiated military rule. This essentially left organized guerrilla formations with only rear areas—mainly refugee camps in Lebanon and Jordan—and little to no frontline or base area to speak of within occupied Palestine itself. (One of the few exceptions, in a further testament to Gaza’s centrality to the resistance, was a series of Egyptian-sponsored raids originating from the territory in the lead-up to the 1956 Suez Crisis: a distant historical precursor to Al-Aqsa Flood.)

During this earlier period, resistance groups had to creatively adapt the precepts of guerrilla war to the conditions of exile. As pointed out in the 1971 documentary Red Army-PFLP: Declaration of World War (on which more in Part IV): “They make no distinction between front line and rear … for them there is no difference between urban guerrillas and [rural] guerrilla warfare. Urban guerrillas learn on the battlefield, and masses of people make the battlefield their home.” At another point in the film, a PFLP cadre explains that “it is here, the Jerash Mountains stretching along the border between Israel and Jordan, that we choose to be our battleground, to build our base to start war and expand revolution.” The reasoning behind this decision—to build a base sandwiched between two (at the time) mutually-antagonistic bastions of imperialism—recalls that of Mao in “Why is it that Red political power can exist in China?” (1928):

The prolonged splits and wars within the White regime provide a condition for the emergence and persistence of one or more small Red areas under the leadership of the Communist Party amidst the encirclement of the White regime.

As recounted in Part I, the crushing of the Black September uprising rendered even this tenuous foothold on the border of Jordan and occupied Palestine impossible to maintain. In subsequent decades a series of military and diplomatic maneuvers by Israel and its imperialist backers, principally the United States, further eliminated one rear area after another in calculated fashion. Chief among these were Israel’s brutal 1982 invasion of Lebanon (to which the PLO had fled from Jordan and from which it was forced to flee again), followed by its 1985-2000 occupation of south Lebanon; and since 2011 the U.S.-led proxy war on Syria, which paid host to multiple rejectionist factions after the Oslo accords. Alongside these came Israel’s normalization agreements with Egypt in 1979, Jordan in 1994, and four other Arab states in the 2020 Abraham Accords, as well as the creation of the Palestinian Authority (PA) as a counterinsurgent force in the occupied territories themselves.

Israel’s unilateral “disengagement” from the Gaza Strip in 2005 would appear to have bucked this trend, though as PYM points out it was motivated more by the Palestinian “demographic threat” to the rather thin Jewish settler presence there. If Zionist authorities also felt secure in entrusting Gaza to the PA for continued “pacification,” they were swiftly disabused by Hamas’s victory in the 2006 legislative election and its subsequent takeover of the territory in 2007, following an abortive Fatah-led coup attempt. These events effectively converted the Strip into a de facto liberated territory and base area—albeit under crushing blockade—where Hamas and other resistance factions could, in Mao’s words,

carry out their duties of training, self-preservation, and development.

Whether Gaza could be qualified as “strategically located” was another question entirely. Hemmed in from the west by the Mediterranean Sea and on all other sides by the joint Israeli-Egyptian blockade, the apparent lack of strategic depth enjoyed by the resistance—to say nothing of the civilian population—was made painfully clear by a succession of punishing military onslaughts in 2008, 2012, 2014, and 2021 even before the apocalypse of 2023-24.

On paper, this is a far more disadvantageous position than that faced by any CPC revolutionary base area after the Long March. Yan’an, for example, was chosen as the destination of that arduous trek partly for its closeness to the anti-Japanese front and to Soviet supply lines (as well as those from the rest of KMT-held North China after the formation of the Second United Front). And when the civil war resumed in force after World War II, the new CPC base in Manchuria directly bordered both the Soviet Union and north Korea, which offered expansive rear areas and near-inexhaustible supply lines for both men and materiel.

Chinese state media report from November 2, 2023 showing footage released by Hamas of a tunnel-based anti-tank operation.

But famously, and more crucially than ever before in the wake of October 7, the Gaza-based resistance has compensated for its conspicuous lack of lateral strategic depth by constructing a gargantuan tunnel network 300 to 450 miles in length (according to the latest Israeli estimates). In other words, as Justin Podur points out, they have literally built vertical strategic depth into the ground. In this way they make up not just for the limited size but also other deficiencies of the physical terrain, as Louis Allday notes: “Gaza’s geography lacks the mountainous and/or dense forested areas that were crucial in other successful guerrilla warfare campaigns—the network of tunnels now effectively fulfills that role.” Max Ajl sums up their combined political, technical, and strategic achievements in terms that echo Cabral:

The resistance… has alloyed ideological commitment, willingness to sacrifice for their people, and technological ingenuity into armed capacity capable of going head-to-head with a nuclear power from underground tunnels, the ‘rear base’ and physical strategic depth needed for guerrilla insurgency. The concrete is their mountains.

Indeed the near-total devastation of Gaza’s built infrastructure—both a byproduct and an intentional manifestation of Israel’s genocidal aims—has turned concrete into “mountains” even above ground as well. Jon Elmer of the Electronic Intifada has highlighted that resistance forces now routinely use the rubble from Israeli airstrikes as advantageous terrain to attack invading ground troops from all angles. At times they even “walk through walls” as former IDF chief of staff Aviv Kochavi once boasted of doing, through homes not yet depopulated of their civilian inhabitants, in his quasi-Deleuzian counterinsurgent operational theory. Even as Israeli forces boldly claim “full operational control” over most of the Strip, penning some 1.5 million civilians into Rafah for what they believe to be a final eliminatory push, the resistance retains its capacity to wage a guerrilla war of maneuver even as far north as Gaza City. Just as Mao prescribed, everywhere they “convert the enemy’s rear into an additional front. Thus the enemy will never be able to stop fighting.”

The Axis of Resistance: encirclement and counter-encirclement

If the game of ‘weiqi’ is extended to include the world, there is yet a third form of encirclement as between us and the enemy, namely, the interrelation between the front of aggression and the front of peace. The enemy encircles China, the Soviet Union, France and Czechoslovakia with his front of aggression, while we counter-encircle Germany, Japan and Italy with our front of peace. But our encirclement, like the hand of Buddha, will turn into the Mountain of Five Elements lying athwart the Universe, and the modern Sun Wukongs—the fascist aggressors—will finally be buried underneath it, never to rise again.

— Mao Zedong, “On Protracted War” (1938)

When Mao wrote these words a year before the outbreak of World War II in Europe, China’s war of resistance against Japan could justly have been considered the epicenter of the world anti-fascist struggle. It would be no exaggeration to say that Gaza occupies this position today. As such we cannot ignore that as the Zionist “front of aggression” encircles and seemingly lays waste to the very possibility of human life in Gaza, the resistance there compensates for its lack of strategic depth not just through tunnel warfare but through its own “front of peace”: the Axis of Resistance. Primarily comprising the Lebanese resistance formation Hezbollah, the Ansarallah movement of Yemen (also known as the “Houthis”), and the Islamic Resistance in Iraq, the non-Palestinian members of this alliance have since October 7 leveraged their strategic locations and access to state-level resources—and in Ansarallah’s case, de facto state status—to effect an asymmetric counter-encirclement of Israel and its regional backers.

The activities of the Islamic Resistance in Iraq serve to illustrate the recursive nature of “encirclement” in this context. Though their membership substantially overlaps with that of the Iraqi state-sponsored Popular Mobilization Forces, they lack some of their allies’ long-range firepower and have only rarely been able to target Israel directly. But their area of operation includes dozens of U.S. military bases—globally part of a world-encircling network of around 800, but locally quite isolated and exposed. The Islamic Resistance has exploited this fact to maximum effect given its capabilities, launching over 170 attacks on U.S. bases in Iraq and Syria since October 17 in a campaign both to expel occupying forces from the region and to raise the costs for their support of the Israeli genocide. One of these attacks scored a major coup on January 28, 2024 by killing three U.S. troops at the Tower 22 base in Jordan.

More strategically located vis-à-vis Israel, and with decades more fighting experience from its victorious fifteen-year campaign to liberate southern Lebanon and its historic defeat of another Israeli invasion in 2006, is Hezbollah. Starting on October 8, just a day after Al-Aqsa Flood, it has by its own count launched over a thousand cross-border operations mainly against Israeli military bases, surveillance posts, and settlements in the north. According to statements by Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah on January 5 and February 4, Hezbollah has thereby forced the evacuation of 230,000 settlers from northern occupied Palestine; tied down 120,000 Israeli ground troops and fully half of its navy and air force, leaving them unavailable for the assault on Gaza; and inflicted over 2000 direct casualties. According to a recent survey, 60% of Lebanese believe “the presence of the resistance, its demonstration of its growing strength, and its revealing of an important aspect of these capabilities during the current confrontations” are responsible for preventing a comprehensive Israeli attack on the country.

Chinese state media report from November 21, 2023 showing footage released by Ansarallah of their seizure of the Galaxy Leader ship two days earlier.

The most creative and unlikely intervention has come from Yemen’s Ansarallah, the de facto governing authorities of a country that has itself suffered eight years of unremitting siege and bombardment from U.S.-backed Saudi and Emirati forces. Since November 18, when they sensationally boarded and captured the Galaxy Leader, they have enforced a blockade on Israeli-bound or Israeli-linked shipping through the Bab al-Mandab strait at the southern end of the Red Sea. In total Ansarallah claims to have targeted at least 48 vessels affiliated with Israel (or the U.S. and UK, since the latter began launching joint airstrikes on Yemen on January 11) and has pledged to continue until the Israeli siege on Gaza ends. Contrary to patronizing Western narratives that paint their actions as mere piracy, Max Ajl emphasizes that “the Yemeni armed forces understand themselves as fighting a mass mobilizing peoples’ war, based on ideological hardening of troops and sophisticated tactics to neutralize technological superiority, learned during their apprenticeship with Hezbollah.”

In an ironic echo of the practice of corporate “over-compliance” with U.S. sanctions on Iran and Cuba, four of the world’s five largest shipping companies have suspended their Red Sea routes entirely. Freight volume passing through the Red Sea has plummeted by a stunning 80% from pre-crisis levels according to the Kiel Trade Indicator; traffic specifically at the southern Israeli port of Eilat has cratered by 85%. Given its centrality to global trade, much attention has focused unsurprisingly on China’s positioning. Its public rejection of U.S. entreaties to join the ill-fated “Operation Prosperity Guardian,” and its condemnation of unilateral aggression against Yemen, is probably not unrelated to the growing trend of vessels signaling “all Chinese crew” to avoid targeting by Ansarallah. Meanwhile state-owned shipping company COSCO has stopped traffic to Israeli ports entirely, following in the footsteps of its Hong Kong subsidiary OOCL and Taiwan-based Evergreen’s refusal to handle Israeli cargo.

According to historian Amal Saad, the Axis of Resistance has thus managed to impose an entirely new like-for-like strategic equation on Israel in the wake of October 7: “displacement for displacement” in the case of Hezbollah, and “siege for siege” for Ansarallah. Together this constitutes a regional counter-encirclement that partially negates any strategic depth Israel may enjoy vis-à-vis Gaza alone, even with the active collusion of its neighbors Egypt and Jordan. Khalil Harb notes the unprecedented nature of this strategic conjuncture:

For the first time in its 76-year history… the occupation state is today grappling with buffer zones inside Israel.

A common Western smear against the Axis is that its various members act essentially as proxies for their main state sponsor, the Islamic Republic of Iran. Their actual operational practice since October 7 has conclusively refuted this charge. In a January 3 speech commemorating the anniversary of Qassem Soleimani’s martyrdom, Hassan Nasrallah pointed out that the late Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps commander had always pushed for resistance factions to avoid dependence on Iran and attain material self-sufficiency and operational autonomy—objectives which have now been met. “In this grand vision,” he noted,

no one commands another. We discuss. We share opinions. We learn from each other. But each one decides his own pathway in his own country based on what is good for his country.

From a technical standpoint, Max Ajl notes, “Iranian weapons and training are free, representing ‘the possibility of access to weapons for the poor.’ Indeed, their blueprints are often open-access or freely shared from Iran to its state and sub-state partners.” This dynamic stands in stark contrast to the dependency that the United States forces on most of its Global South vassals (particularly in the region, e.g. Egypt and Saudi Arabia) as captive markets for its domestic arms industry. Rather it loosely resembles, albeit in an even less transactional form, China’s active efforts to promote industrialization and scaling of the value chain by its partners in the Belt and Road Initiative. Indeed, Matteo Capasso has convincingly argued that China’s single greatest material contribution to Palestinian resistance today is its deepening bilateral trade with Iran, enabling the country to support its Axis partners in building out their autonomous capabilities even under a vicious U.S. sanctions regime.

In Palestine itself this essentially decentralized form of coordinated resistance has been mirrored in the “unity of the fields” between Gaza, the West Bank, and the ‘48 territories. With the Unity Intifada of May 2021, “for the first time in nearly two decades, Palestinian resistance, whether armed or unarmed, was no longer confined to a single territorial enclave.” Unfortunately that volume of open resistance within ‘48 Palestine has not been matched since October 7, owing to depoliticization and normalization within nearly all nominally legal Palestinian formations. But the year 2023 did witness a remarkable 350% increase in West Bank resistance operations over the previous year, from 170 to 608.

Regarding the unity of the fields, in terms that apply equally to the broader regional practice of the Resistance Axis since October 7, Abdaljawad Omar remarks aptly that

This ambiguity means that the occupying state must design its military operations taking into account the possibility of any small confrontation developing into a multi-front regional war. At the same time, the lack of clarity of the concept gives the possibility of evasion, such that the resistance determines when to intervene, or what its red lines are, or when the response will be broad and from all geographies, and when it will be limited and from a specific location, or when there will be no response at all.