Armando Carías is a journalist, theater director, and playwright with a distinguished trajectory in the world of Venezuelan culture. His plays have been widely published and were recently honored at Venezuela and Cuba’s national book fairs.

In this interview, Carías delves into various aspects of Venezuelan theater, particularly children’s theater. He also talks about his work as director of Comunicalle, an experimental theater ensemble, and about the unresolved challenges facing the Bolivarian Process in the sphere of cultural production.

Cira Pascual Marquina: Could you discuss your dramaturgical work and its relation to the broader Venezuelan cultural landscape?

Armando Carías: Dramaturgical work has historically been considered a minor genre within literature. Only a fraction of theater makes its way to publication and distribution, and it primarily exists in the sphere of performance. I’m a proponent of the idea that theater should be read and, of course, performed.

Fortunately, my work has been widely published, including my children’s plays. This is a double achievement, since children’s literature is often marginalized by publishers. Your question prompts a reflection on dramaturgy as a literary genre, as a genre that is as valid and interesting as a novel, a short story, poetry, or an essay.

When I was honored at Venezuela’s International Book Fair [FILVEN], I was deeply moved. I was the first playwright to receive such recognition. Moreover, I’m a playwright who writes theater for children, which is even more “fringe.” I feel like the recognition was also an acknowledgment of the marvelous group of colleagues who have dedicated themselves to the genre of children’s literature.

CPM: If dramaturgical work is considered a “minor genre” and children’s theater even more so, why do you concentrate on writing and directing plays for children?

AC: I often challenge the notion that children are solely the future. Childhood is the present. Children matter to us now and, of course, when they become teenagers and adults, they will matter too.

For me, a pressing question is: what about childhood today? What are the cultural rights of children? This is a plea I have made in a warmhearted way to the Bolivarian Revolution. We have to establish concrete cultural policies for children! The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, UNESCO’s charter, our Constitution, and the Organic Law for the Protection of Children and Adolescents each state that children must be a priority and in all respects. We should put our money where our mouth is.

Concrete actions, such as establishing schools for children’s theater, music, and visual arts, and incorporating kid-centric activities in cultural spaces like museums and theaters, are essential. As the poet Velia Bosch eloquently stated, children have historically been relegated to being second-class citizens. In recent years we have witnessed a shift. My dear friend [Culture Minister] Ernesto Villegas has taken up the challenge of putting kids in the center of things. Still, there is a lot more to do!

CPM: Your work is deeply rooted in Venezuelan culture and connected to an emancipatory vision. Could you share your views on theater-making?

AC: President Nicolás Maduro just launched “Misión Viva Venezuela.” During the inaugural speech, the president acknowledged that the initiative was born out of criticism and demands made by practitioners and supporters of popular music, dance, storytelling, poetry, etc. It was also put forward by artists linked to what we call “traditional culture” but which is often mistakenly referred to as “folklore.” Misión Viva Venezuela is a popular victory.

The mission has seven pillars, and one of them is children. Other pillars are education and the renewal of cultural infrastructure. In other words, Misión Viva Venezuela is not an announcement to simply fill a hall or broadcast on TV. The mission aims to promote a genuine appreciation of Venezuelan culture.

I wanted to begin by saying that, because I’m part of a movement that is committed to Venezuelan culture. Now we can turn to my own reflections on theater.

My concept of cultural production, my vision if you will, comes from my mentors, who were researchers, musicians, poets, and performers influenced by traditional culture. They blurred the boundaries between the culture that was historically banned from concert halls and museums, on the one hand, and the so-called “fine arts,” on the other. At Comunicalle, we’ve been very fortunate because we haven’t been constrained by “rules”: we have been able to incorporate unconventional set designs and combine children’s plays with rock music while drawing inspiration from our national culture and our experiences.

Most of the work that we do stems from a militant attachment to our cultural roots. For instance, Comunicalle performed at a march yesterday. What we did was use our drums and “puya” percussion to accompany the political slogans that came from the people. In so doing, we are faithful to the maroon heritage that gave birth to the first revolution of the 21st century.

By honoring our diverse cultural heritage, we remain faithful to our roots.

CPM: I can perceive the influence of Augusto Boal’s “Theater of the Oppressed” in your work. Can you talk about this?

AC: My dramaturgical work can be divided into two periods. I spent 28 years as the director of “El Chichón.” That was the Universidad Central de Venezuela’s children’s theater, which I founded in 1978. I retired from that post some 20 years ago, in the heyday of the Bolivarian Revolution.

Then I began to work as a journalist. I founded Venezuela’s youth public radio station [RNV Activa]. There, we promoted a “fresh” approach to news coverage, and most programs were led by young people who were very politicized.

However, in the past ten years, I have returned to theater full-time. I head the Ministry of Communication’s “Communicational Art Office,” otherwise known as “Comunicalle.” Comunicalle is a collective by and for the people, a hybrid initiative that brings theater together with music, dance, and circus. It’s a project that aims to inform and educate in a playful and non-prescriptive manner.

Comunicalle indeed takes inspiration from Augusto Boal’s “Theater of the Oppressed,” because he created a poetic methodology for political theater. He developed, for instance, what came to be known as “image theater,” which is an almost instantaneous street performance linked to the conjuncture. The spontaneity of these actions can infuse the moment with political content.

We refer to most of our work as “communicational actions” because, as I said before, we are a communication collective. For example, in addition to performing in Chavista marches, we organize interventions in the context of national holidays and we perform short street plays delving into issues such as gender-based violence or the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza.

But Boal is not our only influence: there is a long tradition of street theater in Venezuela that is very dear to us. Perhaps it lacks the discipline of the Theater of the Oppressed and it isn’t as fully developed as Cali’s Experimental Theater movement, but we have a long history of traffic light interventions and muralism. These actions were important to express political dissidence before Chávez, and they were often criminalized for their anti-establishment content.

Finally, in the discipline that we practice (which is more than theater because it goes beyond genres and disciplines), we are greatly inspired by Cuba’s Escambray Group. That was a guerrilla theater collective that worked to politicize campesinos who were being co-opted by Jehovah’s Witnesses. Their work is very relevant today because of the emergence of ultra-conservative evangelical groups in our country and the whole continent.

CPM: Two Venezuelan playwrights, Aquiles Nazoa and César Rengifo, have significantly influenced your work. What can you tell us about their contributions?

AC: For sure, and I’d also like to include Rodolfo Santana in this discussion. However, let’s begin chronologically, starting with Aquiles Nazoa.

Aquiles stands as one of the towering literary figures of the 20th century. In fact, I wouldn’t just label him as a playwright: he was a writer in the broadest sense of the word. His early pieces were crafted as “theater to be read.” The plays were packed with content, and even his stage directions were written in verse, which makes the reading very enjoyable. He is the great poet of the Venezuelan people and he is also part of our Caracas cityscape, with his verses adorning countless newsstands across Caracas.

Aquiles was a communist and penned beautiful verses dedicated to Fidel Castro and the revolution, earning him recognition in Cuba alongside luminaries like Nicolás Guillen.

Then there is César Rengifo, another committed communist, who depicted Venezuelan history from the point of view of the oppressed: from the resistance of the Indigenous peoples to the Federal War. His play on [19th-century revolutionary leader] Zamora is a masterpiece. Rengifo passed away before Chávez appeared on the scene, but I know that if life hadn’t taken him, he would have portrayed Chávez in his work.

Finally, there is Rodolfo Santana, whose dramaturgical work is often overlooked but influences my artistic production. I had the privilege of publishing his only children’s play, “La Guerra de Tío Tigre y Tío Conejo.” It is a marvelous story based on a Venezuelan tradition illustrating how intelligence and swiftness can triumph over brute force.

Many more playwrights influenced me, but these three are particularly important because their work has deep roots in our history and cultural traditions, and also due to their commitment to the pueblo and not to the elites.

CPM: I recently saw Comunicalle perform “Bufonadas” [“Horseplay”] outside Ksa La Minka in Caracas. It’s an amazing piece of theater that was beautifully performed in that street setting. Can you tell us the story behind Bufonadas?

AC: “Bufonadas,” based on a text by Rafael Salazar, is a good example of our artistic production. We adapted the piece, introduced the figure of the jester [bufón], and gave the play a new name. Its first performances were at the Teresa Carreño Theater, but the best stage is of course the street, which is what you experienced in the performance outside Ksa La Minka.

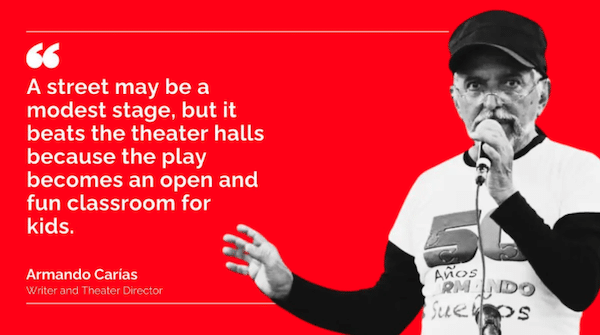

A street may be a modest stage, but it beats the theater halls because the play becomes an open and fun classroom for kids.

“Bufonadas” is a journey through different cultural expressions around Venezuela, a synthesis of cultural syncretism going back to our Indigenous, Black, and Spanish roots. We take our cultural traditions seriously, while we make a tongue-in-cheek salute to the “great culture” that Spain violently bequeathed to us.

“Bufonadas” is a full-fledged production for children that is often enjoyed by adults. However, most of the work by Comunicalle is more succinct than “Bufonadas.” That’s why, when you go to Plaza Bolivar in Caracas, you may run into a five-minute intervention inspired by Venezuelan history. Likewise, on Fridays at 5 pm, near Parque Carabobo metro station [Caracas], you will often find a circle of plastic stools “dressed-up” and ready for a short play about the genocide in Palestine or about March 8. Neighbors, passers-by, and lovers who are walking around the park will spontaneously join us for performances that blend a social critique with informative narratives, often shedding light on state-run initiatives such as the Humanized Childbirth Plan.

We’re not merely a theater group; we’re a media project occupying the streets of Caracas rather than the airwaves.

CPM: Finally, what are the pending tasks for the Bolivarian Process when it comes to culture?

AC: As you know, taking political power doesn’t always come with taking economic power, and the same can be said for culture. Cultural paradigms evolve at a slower pace. They are often entrenched in notions confined to traditional spaces like concert halls and museums.

Further, our society is subjected to the homogenizing effects of the culture industry. This phenomenon, of course, is not unique to Venezuela: I just came back from Cuba, and I was surprised that the youth there is no different from the Venezuelan youth or the youth of the Global North: they are glued to their phones, they listen to the same music, they dress the same way, and they sport the same tattoos. I refrain from making judgments, but the truth is that the global trend tends to obscure local culture.

As a wise poet friend once remarked, when it comes to culture, our task resembles that of a mechanic fixing a car while it’s still in motion. Our revolution’s cultural project demands continued vigilance and proactive measures to safeguard and enrich our heritage.