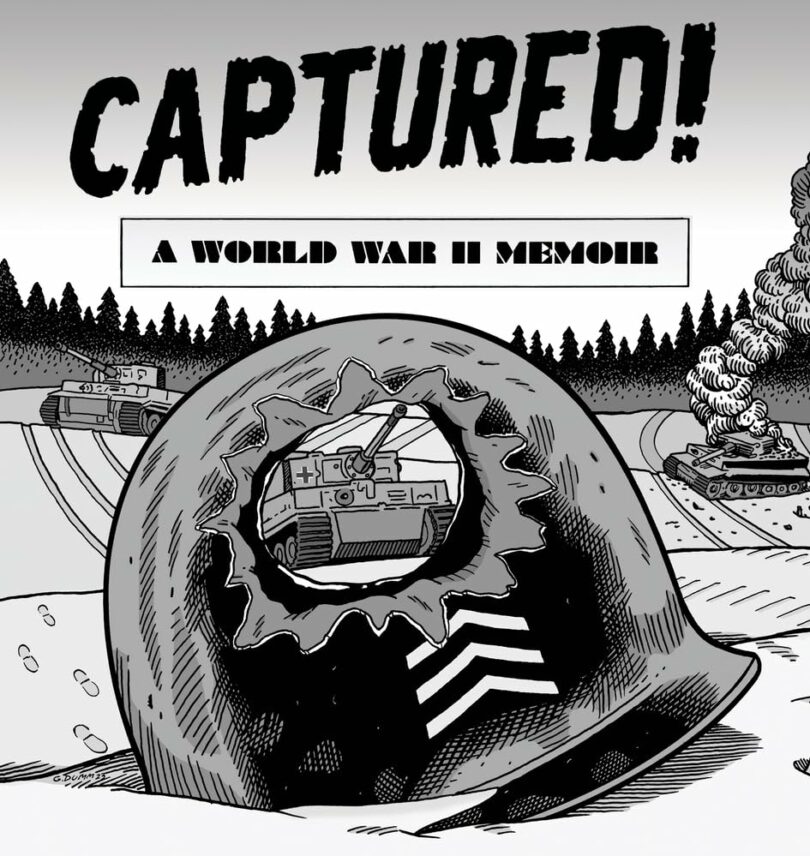

Hugh O’Neill, Captured! A World War II Memoir, illustrated by Gary Dumm and edited by Scott MacGregor (Gatekeeper Press, 2023), 150 pages, $24.99.

So much time has now passed, the living memories of the 1940s remain only with the elderly, and even the obituaries in the flagging daily press grow fewer. Foreign policy blunders and indecisive conflicts have clouded if not destroyed the sense of national unity that existed, for a while, when the enemy had the face of palpable Nazism and fascism. Wartime memories borrowed and dramatized seem more real, less cliche in the best of European art films and television series now circulating via streaming services.

Oddball, individual experiences of Americans even more so. We have forgotten, for instance, that the spread of blues and country music arrived with migration to the north for jobs and the proliferation of small label records. Or that gay and lesbian cultures grew rapidly with the dislocation of young people into new cities and new jobs. Most fascinating, for some of us, is the appearance of the bohemian—soon after to become an important subculture leading, in its way, to the counterculture of the 1960s.

Veteran Cleveland writer and photographer Scott MacGregor recovered a manuscript written by his uncle Hugh O’Neill, which turned into Captured! A World War II Memoir. In it, O’Neill weaves a real-life tale of his life as a prisoner of the Germans in the last year of the Second World War and Cleveland comic artist Gary Dumm, who has worked with the best of the genre, Harvey Pekar in particular, provides vivid illustrations.

To say it is a lively tale would be a serious understatement. But the key to the narrative is elsewhere, in the deeply personal, even philosophical reflections of the protagonist. By early 1945, O’Neill had managed to survive. Driven back from their attempt to defeat Russia and then from their occupation of the Low Countries, the Germans counterattacked in December 1944. O’Neill and others, sent on a reconnaissance mission, fell into German hands. Thenceforth they march, march, and march, without adequate clothing or food, leaving behind the dead and the disabled unable to continue. The filth and absence of clean clothes or adequate sanitary facilities, even of water for extended periods, made this a death march for many but not for our protagonist. O’Neill wonders again and again how he made it through.

Each man was, in a real sense, on his own. The possession of anything, like a toothbrush, was such a luxury that it could disappear. And yet there were also moments, like the spontaneous singing on an early night of the march, that reasserted a certain humanity and the will to survive.

The “secret of life for the prisoner” seems to have been an existential awareness of events all around (37). Crowding in a shelter or train car without going violently mad; accepting the little food that was offered without question, no matter how dreadful; and hoping—an act simultaneously diminished and elevated by the appearance of British bombers.

They were not prisoners in the death camps. They were—or would have been at an earlier time in the war—en route to a prisoner of war camp. Now they were merely marching and inevitably ruminating to themselves. “War, as men experience it, is a complete mess in which the present is a void” (62). This passage alone marks the protagonist not only as a born writer but as a man given to philosophy wherever he finds himself.

They march through Bavaria, like some other large sections of Germany hardly touched by the war. They watch overhead as friendly bombers learn to waggle their wings and signal to them that the next village over is to be destroyed by their bombs, setting off fires, killing every German civilian in sight—as they would soon see marching through. This is the kind of insight, requiring profound reflection, lacking in any but the best U.S. narratives of the war.

O’Neill also notices that the Germans guarding them make careful racial distinctions among the prisoners. Some soldiers from India, part of the British troops, thus march along until they realize their execution was at hand and then, chanting in what he later learned was Hindustanti, utter “God is truth but man is born to die, God is true, but man is born to die” before being executed, lacking (as the author says) only a funeral pyre. The other “undermensch,” mostly Slavs but especially Poles, were treated with utter contempt. Thus, a white American survived, to march on.

After other adventures, some almost unbelievable anywhere or any time except during war, the soldiers surround them, in turn surrounded by Allied troops moving in, as “the knowledge they were to take our places as prisoners” sunk in (122). Liberation had come.

Or had it? MacGregor’s postscript explains the lucidity and insight of the erstwhile GI: O’Neill had a poetic soul that had allowed him to survive. He also had post-traumatic stress disorder. Returning to college at Berkeley on the GI Bill, he married, had a daughter, and fled marriage and career for Big Sur, the famous hangout of erotic novelist Henry Miller. He and other Bohemians, of all genders, raised vegetables, gathered abalone from the seashore, spent serious time in the mineral baths, and famously had a lot of sex. He painted and wrote poetry.

Somewhere in the 1950s, O’Neill left Big Sur for newspaper work on the West Coast and then Hawaii, married again, divorced again, and once again fled civilization, this time for a Buddhist commune. He then returned to newspaper work, traveled frequently, lived in Ireland for a while, and in 2001 dropped dead in Port Townsend, Washington. MacGregor traveled there, joining his sisters in cleaning out the small remnants of O’Neill’s stuff, including the typed memoir.

No moral is drawn, but the illustrations provided by Dumm offer typically understated but eloquent hints. Suffering must be documented. Dumm’s last drawing is the window box observed by O’Neill in one of the last towns he passed through. A crumbled building held a window box with bright red, blooming geraniums. When he saw it, he knew that, for him, the war had ended. At least in life if not in his memories.