Frank Hadesbeck tried and failed to write his life story for years, yet none of his attempts came close to conveying his experience in pivotal events of the 20th century, from the Spanish Civil War to the Cold War. Hadesbeck was no Dashiell Hammett, though his life, the subject of Dennis Gruending’s new biography, is almost a mirror-image of Hammett’s, the celebrated mid-century American writer of hardboiled detective fiction and Hollywood screenplays (The Thin Man, The Maltese Falcon). Whereas Hammett’s experience working as a Pinkerton detective in San Francisco in the 1930s supplied rich material for his books and scripts, his evolving sympathies with the trade unionists and other subjects of his surveillance brought him to the attention of U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy’s House Un-American Committee, which censored his writing and landed him in prison in 1951. Hadesbeck, by contrast, fought alongside communists in the Spanish Civil War and on his return to western Canada was enlisted by the RCMP to spy on them. Only his RCMP handlers knew him as “S.A. 810,” or “Secret Agent 810” when he joined the Alberta and then Saskatchewan Communist parties to snoop and trade in party documents, especially membership lists of names and addresses, and to track members, associates, and fellow travellers for nearly 40 years. He kept tabs on, among other things, those involved in the formation of Medicare in Saskatchewan, viewed initially as a “communist plot.” Against all RCMP norms and injunctions to the contrary, Hadesbeck kept detailed notes.

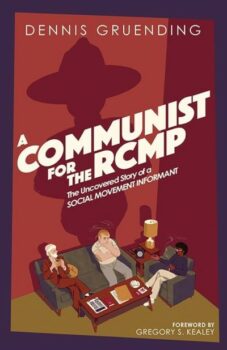

A Communist for the RCMP: The Uncovered Story of a Social Movement Informant

Dennis Gruending

Between the Lines, 2024

How the notes came into Gruending’s hands, described in the preface, is a story almost as riveting as Hadesbeck’s spying in the unlikely landscapes of the southern prairies and the foothills of Alberta. Gruending’s reputation rests chiefly on several previous books, among them biographies of more respectable figures like former Supreme Court Justice Emmett Hall, who shaped Medicare as a national program, and Allan Blakeney, a civil servant in the Tommy Douglas Saskatchewan CCF government and then NDP premier from 1971 to 1982. In taking on the life of Hadesbeck, Gruending has an entirely different kind of subject on his hands, a shady and conflicted character who informed on the very communities that produced Hall, Blakeney, and Gruending himself, briefly a Saskatchewan NDP Member of Parliament in 1999-2000. Perhaps most sensationally, Hadesbeck compiled “Watch Out” lists of communists and associates and their addresses to be monitored by the RCMP for potential unlawful activity, the more readily to be rounded up without warrants and on short notice in the event the Cold War became a hot one, as it did at the outbreak of the Second World War when over 100 Communist Party members were interned across Canada.

Tactics generally found only in spy fiction

In his foreward to Gruending’s book, University of New Brunswick historian Greg S. Kealey spells out the special significance of Hadesbeck’s detailed note-taking and Gruending’s publication of his biography based on those notes. They tell a story that “stands almost unique in the Canadian literature of domestic spying,” writes Kealey, in providing specifics of RCMP “tactics generally found only in spy fiction.” Those tactics include the roundabout ways of shepherding potential informers to untraceable meetings with shadowy security officials. In the case of Hadesbeck, recently returned from fighting in Spain, we find him broke, looking for work, and hanging out in a pool hall in Taber, Alberta. A fellow pool player strikes up a conversation. After a while, the new friend nonchalantly suggests he go see a Mr. Gilchrist over at the drugstore. Gilchrist gives Hadesbeck ten bucks and promises him a job. A few days later, he gives him ten dollars more and instructs him to take the bus to Lethbridge, about 50 kilometres away. There Hadesbeck is told to take a room at the Windsor Hotel, where “someone will find” him. After some time, he is approached by a Mr. Frank, a realtor he later learns is operating undercover for the RCMP. Frank takes him to meet Herbert Darling, Commanding Officer of the Lethbridge detachment.

The RCMP’s reticence in verifying these identities and details requires Gruending to imitate the kind of detective work that Hadesbeck also undertakes in tracking down his targeted “suspects” to complete his reports. Gruending looks into the names and characters in the notes. He finds the 1913 immigration record of the guy in the pool hall, which does not fully explain how the spelling of his name as “Captain” changes to “Capton” in Hadesbeck’s notes, which could be a mere spelling error or indicate a too-loosely assumed name, as is suggested by similarly flimsy identities and changing names in Hadesbeck’s world. The druggist Gilchrist is tracked down by an alert librarian at the University of Calgary, who finds someone of that name registered as a pharmacist and on the voter’s list in Lethbridge within the dates recorded in Hadesbeck’s notes. That Gilchrist died in Red Deer a few years later and his relationship to the RCMP remains a mystery.

The added twist that the story is true

While Gruending convincingly presents Hadesbeck’s story as an episode in the building of the Canadian surveillance state—as do Kealey and Hadesbeck himself—his detective work results in a biography that often reads as spy fiction, with the added twist that the story is true. Hadesbeck’s notes similarly tend towards more literary genres of writing, like spy or detective fiction, as Kealey remarks. In Gruending’s hands, the story even sometimes resembles a novel of social density when characters are given complex backgrounds. This is what happens in the case of the RCMP’s Herbert Darling. Hadesbeck meets Darling just that one time in the seedy Windsor Hotel in Lethbridge and never sees him again, though Darling’s career in the RCMP seems to loom over Hadesbeck’s. Immigration records are cited documenting Darling’s immigration from Wales in 1913 with his wife Mary. His rapid rise through the ranks of the North-West Mounted Police, and, after 1920, the RCMP, is traced in some detail, showing his promotions to detective, to supervisor of officers going undercover, even to assistant commissioner stationed in Edmonton by the end of the 1940s.

But before that, Darling’s life story takes a few turns. By 1916, just three years after their arrival in Canada, he and Mary have two children, but the kids are back in England with Mary. Darling’s RCMP file contains letters from her described as “anguished” and complaining that her “separation allowance” is not enough to live on in England. She asks about her husband’s whereabouts, suggesting their marriage has broken down and he has gone missing, at least to her. This backstory to Hadesbeck’s meeting with Darling in the Windsor Hotel is typical but also typically unresolved in Gruending’s account, pointing to a richer story about Darling and the many others who populated Hadesbeck’s experience. They form narrative possibilities that a novel or screenplay could productively develop and explore. Why did Mary pack up the kids and return to England? Darling is reportedly seen in Europe around that time, but where and why, exactly, and why Mary didn’t know, is unexplained. Questions arise and become more or less narratively urgent as do the many national security mysteries raised by Darling’s appearances and disappearances in Hadesbeck’s story.

RCMP officers during weapons inspection, 1957. (Photo courtesy Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN No. 4949181)

To revel in such literary potentials of A Communist for the RCMP is not to diminish but to enhance its political implications. The subject matter necessarily taps into spy and detective fiction, including the convention of the detective-narrator’s combined sympathy and disgust with his morally and legally compromised characters. Gruending overcomes his own ambivalence about Hadesbeck’s opportunism and dishonesty by using the domestic spy’s story to broach another: the story of how national security threats are calculated and miscalculated, then and now. In among his research and Hadesbeck’s notes, Gruending weaves brief but critical accounts of the historical context, including, notably, the Indigenous context, with the effect of revealing suggestive linkages, or at least intersections, with the founding myths of Medicare and the RCMP.

Darling was first hired by the North-West Mounted Police as it was transforming into the RCMP. He not only hovers over Hadesbeck’s career as an informant but helped to shape the RCMP in his own image as “relentlessly anti-communist.” Domestic security targets in the prairies were expanding from unsettled and suppressed Indigenous resistance to include the European immigrants displacing them, immigrants like Hadesbeck, who arrived from Hungary with his family in 1907 when he was two years old. A young adult at loose ends in the Dirty Thirties, he signs up to fight with the International Brigades supporting the republicans in Spain, where he finds himself under surveillance and taking orders from the Communist International organization known as the Comintern. Back in Alberta by 1939, he then benefits from the banning of the Communist Party (CP) in Canada at the outbreak of World War Two. Hadesbeck’s dual loyalties are in demand as party members move back and forth between the CP and the CCF-NDP amidst the distant crises of Stalinism and communism and very local experiments with pilot test projects for Medicare in three Saskatchewan health regions beginning in 1957 (my hometown health region of Assiniboia among them). The care taken to provide this historical background helps us to locate Hadesbeck and offers hard-won insight into the pitfalls of how to tell friend from foe in questions of domestic security. Gruending is especially strong on the apparently seamless shift in national security interest from communists and communism in Hadesbeck’s time to its current focus on Indigenous and environmental activists opposed to practises of resource extraction, particularly the building of oil pipelines and other ‘critical’ infrastructure.

Motivations for spying and keeping notes

Gruending weighs Hadesbeck’s motivations for spying and for keeping notes, which invites speculation as to why Hadesbeck had such difficulty writing the story himself. Not only was he far less educated and less connected than either Dashiell Hammett or Dennis Gruending, but Hadesbeck was unable to overcome his ambiguous position in relation to his double life. He could not settle the gnarly question of whose side he was on and was fatally confounded by having to speak out of both sides of his mouth. He would have had to recount how he successfully ingratiated himself with communist and progressive activists due to his identification with them, his genuine empathy for fellow farm workers, activists, immigrants, refugees, and he would have to tell also how that success both enabled and required him to betray them all as well as himself by monitoring and sharing the party’s movements, plans, mail, and membership lists with the RCMP. He was paid for his information with cash, jobs, and, from time to time, in-person meetings in two-star motels replete with club steaks and drinks served up by the room service that he could not otherwise afford.

As Dashiell Hammett or Raymond Chandler might have written it, in a crumpled, trench-coated, world-weary voice-over at the end of a convoluted tale, it is perhaps to Hadesbeck’s credit that he couldn’t write the story himself. He couldn’t take sides in telling the story of how he played both sides—that double-voicing is the work of novels, which in fact he attempted but failed to write. We can commend his writing and preservation of the notes, however, and Gruending for putting them to work illuminating Hadesbeck’s strange life and the many otherwise unknowable episodes of recent history in which he played a part. The notes open a view of the RCMP and, by extension, other security agencies now mandated to protect Canada from threat, as possibly susceptible to conflicts of interest as profound as those that kept Hadesbeck from writing his story. As Gruending puts it, whose side are they on? Are they on the side of maintaining the status quo only, as Hadesbeck figured out was the case with the RCMP he worked for? And if so, how can national security attention be re-directed towards what truly threatens us? Climate change and barriers to the free access to information are two threats cited by Gruending that are more immediate and menacing than Soviet-style communism in the southern prairies ever was. Canada needs a security apparatus that can recognize true threats, not one that uncritically sides in advance with forces that deflect from the proper objects of surveillance and pits Canadians against each other.

Dawn Morgan is a retired professor who taught in the English department at St. Thomas University in Fredericton, New Brunswick. She is based in Toronto.