The Third Plenum of the Communist Party of China ended last week. The Third Plenum is a meeting of China’s Communist Party Central Committee composed of 364 members which discusses China’s economic policy for the next several years. As China is a one-party state, in effect this sets out the policies of the government and, in particular, that of President Xi.

What did we learn from the Third Plenum about China’s economic policies? Not very much that we did not already know. According to the state media release, the Plenum agreed that economic policy should concentrate on achieving a new round of “scientific and technological revolution and industrial transformation,” Chinese-style. In the next decade,

education, science and technology, and talents are the basic and strategic support for China’s modernization.

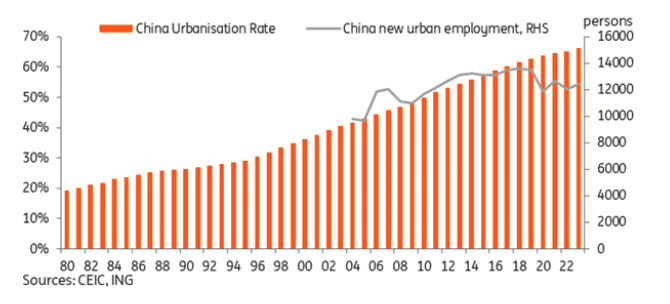

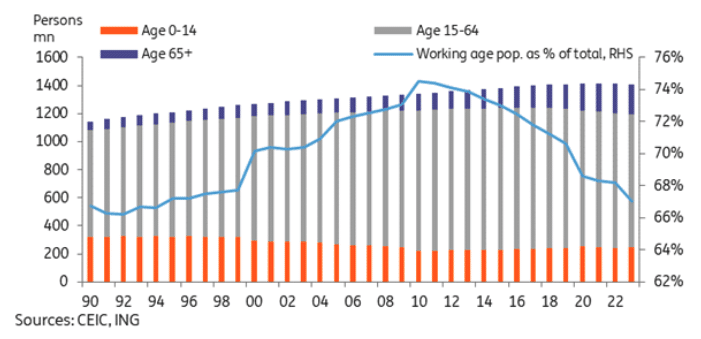

So it appears that the CPC leaders are looking to sustain economic growth and meet all their proclaimed social objectives through what they have called ‘quality growth’. The expansion of the economy mainly through using plentiful labour from the countryside coming into the cities to work in manufacturing, property development and infrastructure is over. It has been over for some time. Urbanisation is slowing.

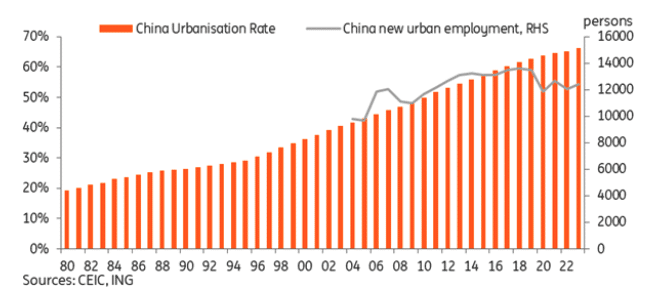

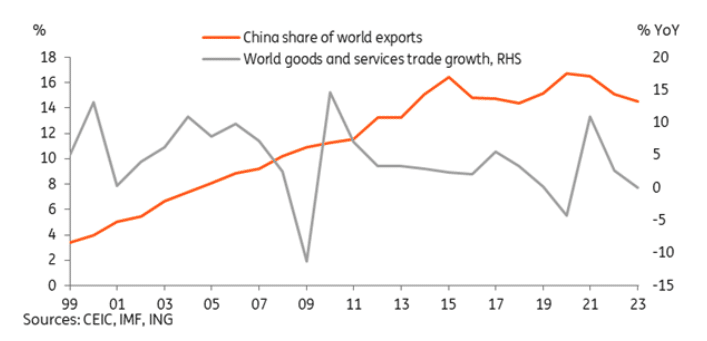

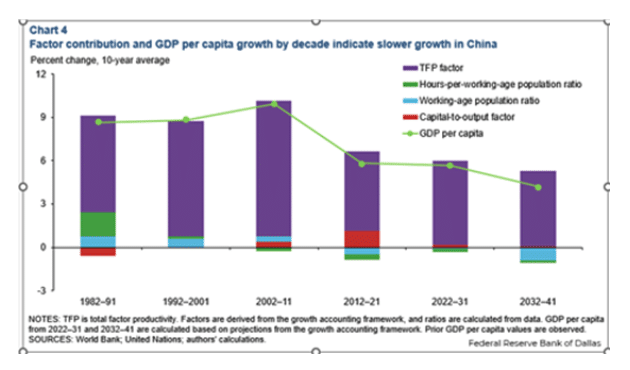

Instead, the Chinese economy has rocketed upwards mainly from a massive increase in productive investment in industry and export-oriented sectors. But that too has reached somewhat of a peak since the Great Recession of 2008-9. The global economic slowdown and stagnation in the major economies since then—what I have called a Long Depression—have also affected the rate of economic growth in China. World trade growth has stagnated and so has China’s share.

China’s real GDP growth has slowed since the Great Recession, although the economy is still expanding at around 5% a year, more than twice as fast as the US economy, the best performing of the top seven capitalist economies.

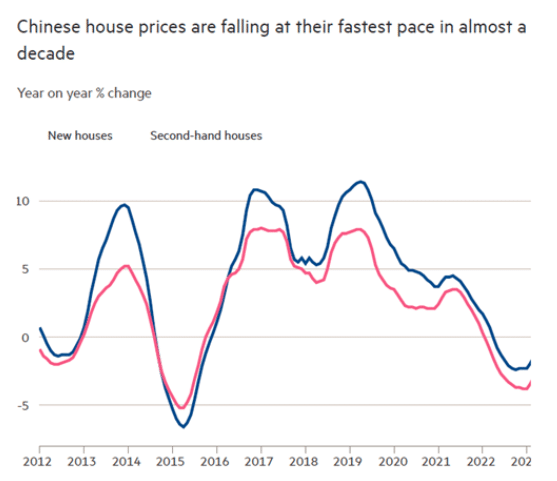

But other causes of slowing growth include the relative exhaustion of labour from the rural areas and also the expansion of unproductive investment in real estate, which eventually ended in a property bust that is still being managed. As I have argued in many previous posts, this was the result of the huge policy mistake that the Chinese government made back in the 1990s in trying to meet the housing needs of a fast-urbanising population through the private sector: ie. homes to buy, financed by mortgages and built by private developers. This housing model used in the West triggered the global financial crash in 2008 and eventually led to a similar property slump in China.

But the key issue for the Third Plenum is the ‘demographic challenge’. China’s population, like many others, is set to fall over the next generation and its working age population will also drop.

Economic growth and further improvements in living standards will increasingly depend on raising the productivity of the labour force. I have argued in previous posts that this is perfectly possible to achieve.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas shows that China’s ‘total factor productivity’ (which is a crude measure of innovation) is growing at 6% a year, while it has been falling in the US. Slower growth but still much faster than G7 economic growth and based on technological success.

But Western media and mainstream economists continue to argue that China’s economy is in deep trouble. Here is the assessment of the UK’s Financial Times:

China’s growth is too slow to provide jobs for legions of unemployed young people. A three-year property slump is hammering personal wealth. Trillions of US dollars in local government debt are choking China’s investment engines. A rapidly ageing society is adding to healthcare and pension burdens. The country has continued to flirt with deflation.

I could deal with these issues one by one. But I have already done so in many previous posts. Suffice it to say that the size of youth unemployment is a serious challenge. There is a sharp mismatch between young graduate students looking for well-paid high -tech jobs, while available employment is still concentrated in lower-paid less skilled work. This is a problem in many economies, including the advanced capitalist economies. The solution, it seems to me, is in the expansion of high-tech sectors, but also in re-training for other jobs.

2) the property slump has been severe. It is no bad thing, however, for property prices to fall sharply so that housing becomes more affordable. The solution from here must be an expansion of public housing, not more private development.

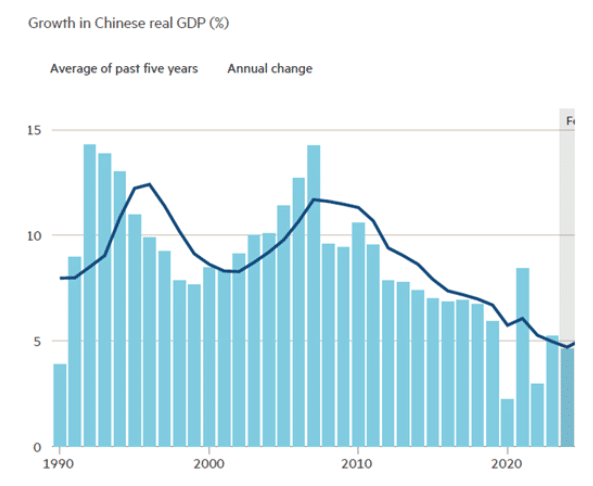

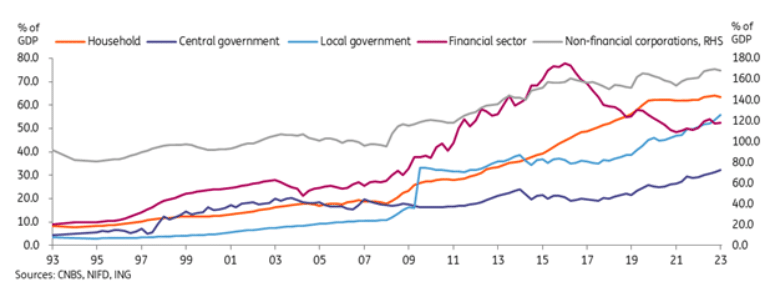

3) as for the debt issue, it’s true that China leverage ratios have surged in past decades, but they are manageable, especially as most of the debt is concentrated in local government sectors and so can be bailed out by central government. And China has a state banking system, state-owned companies and massive FX reserves to cover any losses.

China: debt to GDP

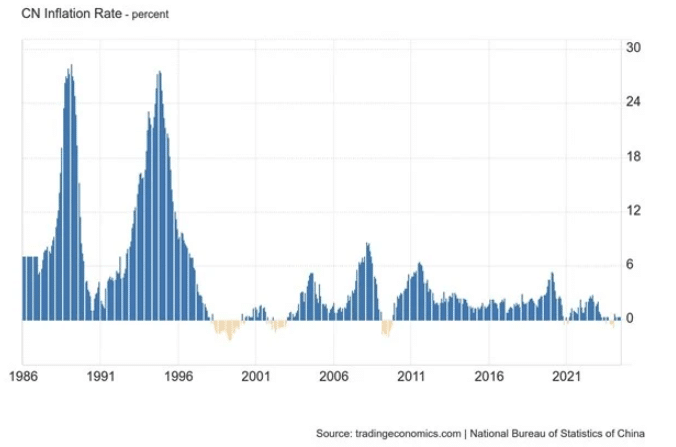

4) Apparently falling consumer prices in China is a bad thing, according to the FT. But is it so bad that basic purchases get cheaper? Is it better to suffer the inflationary spike that consumed Western economies and households in the last two years?

The other critique continually hammered by the likes of the FT and Western economists is that: “Beijing pledged to reorientate its growth model away from an over-reliance on investment and exports towards household consumption. This, western governments have long hoped, would help reduce China’s huge trade surpluses and invigorate global demand.” But “Not only has China failed to deliver on its rebalancing pledges, it has actually regressed.” The FT is upset that “The plenum communique does not pledge to boost consumer spending or rebalance the economy away from investment and exports.”

The FT then goes on to blame China for the US tariff war likely to be accelerated if Donald Trump rewins the presidency in 2025. “Xi and his politburo should realise that China’s trade imbalances are becoming an ever more incendiary issue. Its monthly trade surplus reached an all-time record in June. The resurgence of Donald Trump, who imposed hefty tariffs on Chinese imports during his term as US president, should give real pause for thought.” China is apparently at fault for the trade war, not US government attempts to curb Chinese export success and technology advances.

Once again, the Western media and economists argue for a ‘rebalancing’ by which they mean a switch to a consumer-led, private sector-led economy from the current investment-led, export oriented, state directed one. “The Chinese economy is foundering,” said Eswar Prasad, professor of trade policy at Cornell University and former head of the International Monetary Fund’s China division. “More stimulus to pep up spending and economic overhauls to revive private-sector confidence in China are urgently needed”, he said.

But for me, trying to boost consumer spending and expand the private sector are just not what the Third Plenum should aim for. Actually, the Third Plenum release reminds us that China still has planning, not the centralized one of the Soviet Union, but ‘indicative planning’ with targets set for many sectors. The release said that “We must summarize and evaluate the implementation of the “14th Five-Year Plan” and do a good job in the early planning of the “15th Five-Year Plan”.”

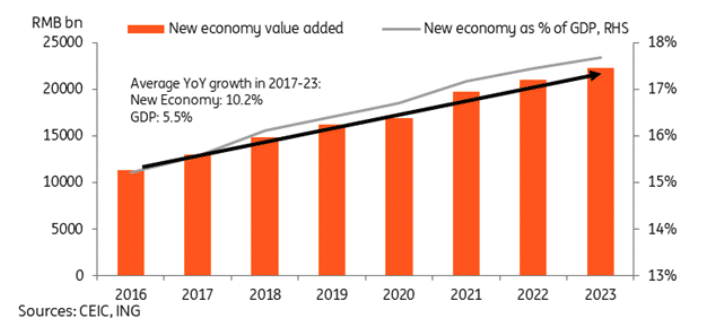

China is fast developing a ‘new economy’ based on high value-added tech sectors. These sectors have significantly outpaced headline GDP growth in recent years. Between 2017 and 2023, the new economy grew by an average of 10.2% per year, far faster than the 5.5% average overall GDP growth.

As a piece in the Asian Times put it:

A common narrative bandied about by the Western business press is that China’s subsidized industries destroy shareholder value because they are not profitable—from residential property to high-speed rail to electric vehicles to solar panels (the subject of the most recent The Economist ‘meltdown’). But what China wants from BYD and Jinko Solar (and the US from Tesla and First Solar) should be affordable EVs and solar panels, not trillion-dollar market-cap stocks. In fact, mega-cap valuations indicate that something has gone seriously awry. Do we really want tech billionaires or do we really want tech? Value is not being destroyed; it’s accruing to consumers ins lower prices, higher quality and/or more innovative products and services.

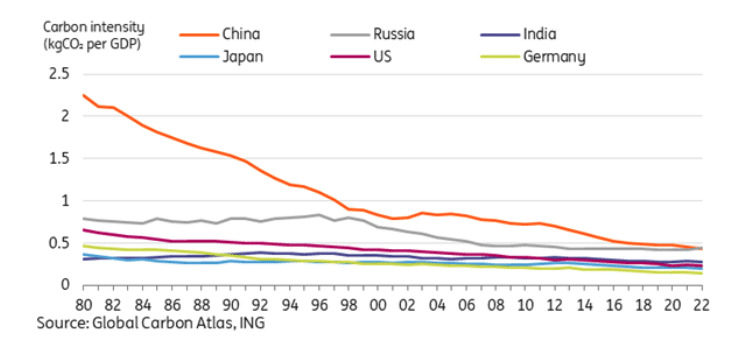

This is very visible in environmental investment. China’s carbon intensity has dropped at an unprecedented pace.

As the Asian Times writer put it:

what is economic success, what is value creation? Maybe, just maybe, it’s the approach that delivers the most tangible improvements in people’s lives, instead of trillion-dollar companies and billionaire CEOs.