The early twentieth century saw a wave of anti-colonial struggles that took the form of the labour strike. In the 1930s, Palestinian workers went on a general strike that turned into a three-year revolution to resist the settler colonial project orchestrated by the British Mandate. In Egypt, workers also went on general strikes demanding the end of British colonial occupation, and in the 1930s workers demanded lower rents in working-class neighbourhoods. After a general strike in 1946, Indian dock workers went on strike against British colonialism. And the list goes on. The strike has been historically extended to attend to anti-colonial and anti-racist struggles, housing injustices, and other social issues. The history of the labour strike is a reminder that capitalism operates as a totality that—while defined by relations of exploitation—encompasses broader social processes than simply production.

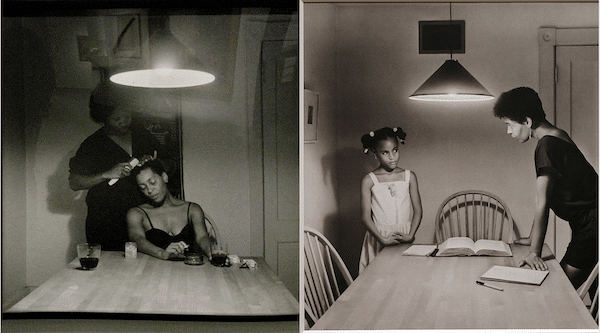

Capitalist social relations structure circulation, consumption, rent, and debt, all elements that bring in colonialism, access to housing, financial markets, migration, and social reproduction as central tenants in the functioning of capitalism. Accounting for the vastness of capitalism’s reach entails thinking about the preconditions that make its accumulation possible, for example, through capitalism’s reliance on unpaid housework. But these preconditions are wider than reproductive labour. They implicate broader gender and race relations through night work, precarity and the gig economy, as well as struggles over homes and housing, education, health care, and border crossing. While there is so much that could fall under this conception of social reproduction, I focus here on the home as a nexus of struggles over labour and struggles over housing—the home as a lease, as a mortgage, as shelter, as a stop in a food delivery app, and as paid and unpaid work. The home is a space of shelter and nurture; it is a site that witnesses all the activities necessary for the reproduction of society, and women have historically carried out a large part of that burden.

Here, access to housing is understood as question of social reproduction. It is not surprising that some of the most important rent strikes in history were led by women.1 The struggle over housing has always been a class issue. It harbours a budding movement against the commodification and financialization of homes. The struggle over housing is also one way to organize around reproductive demands. Unlike labour strikes, rent strikes are mostly illegal in countries around the world. Considered an aberration on the sanctity of property ownership, rent strikes are mostly illegal in countries around the world, yet they embody an important antagonism that could be used to bargain for gains in the sphere of social reproduction. Rent strikes are refusals, negative forms of collective action that produce new processes of living, from collective learning and mutual aid to shared or collectivized reproductive labour. If the labour strike threatens production and the accumulation of capital, then the rent strike threatens consumption processes and property relations that rely on the constant expropriation of tenants. Perhaps thinking about both together could set new parameters to subvert the reproduction of society in its current form under capitalism.

This expansive conception of social reproduction also allows us to think through how class formations are always already racialized and gendered. If this is not clear from the racial makeup of workers in the care sector and the gig economy, then consider the journey of migrant workers. By the time a typical worker arrives in the receiving country, they have already passed through a life of training, education, health care, and other costs of social reproduction in their home country. As Rafeef Ziadah and Adam Hanieh argue, the new country effectively outsources all this labour from the worker’s home country, and they arrive ready to expend their labour power in the market. In this sense, capitalist economies in the Global North “free ride” on the care work put into the production of labour power primarily in the Global South, yet “accords them no monetized value and treats them as if they were free”. This process of course continues in the receiving country through the various ways society continues to be reproduced by paid and unpaid—and often racialized—workers.

These wider processes show how race, racialization, and borders are already implicated in the question of social reproduction. While social reproduction is a necessary condition for constant capital accumulation, this desire for boundless accumulation tends to unsettle the same processes needed for the reproduction of society, including, for example, anti-migrant policies. This, Fraser argues, is “the social-reproductive contradiction of capitalism [that] lies at the root of the so-called crisis of care.” This became clear during the COVID-19 pandemic when many health care and care workers were celebrated as essential workers, but none of those celebrations manifested in material recognition of their labour. Most workers in the care sector are underpaid and overworked and have disproportionately taken the brunt of the pandemic. In the last wave of strike action in the UK in 2023, for example, nurses were given pay offers that effectively amounted to a slightly smaller pay cut given the rising rates of inflation in the country. This hierarchy of skills and pay lies within the logic of capitalism itself rather than a reflection of those jobs. Care work also has a certain specificity in that it requires human contact: tactile, affective, and emotional. While technology has automated many of the activities needed for care work, none of those devices could attend to the care of children or the elderly, a form of work that needs tremendous amounts of emotional, physical, and intellectual labour. Remarking on the robotization of households and care work, through “nursebots,” for example, Silvia Federici asks: “But is this the society we want?”. If this is not the society we want, then anti-capitalist struggle today must encompass struggles over social reproduction.

Anti-capitalist struggle today should entail wider actions than what traditional Marxism has stipulated in theory and practice. All the background conditions required for the accumulation of capital could be mobilized if one looks at what lies behind the production process, or what Nancy Fraser called “boundary struggles over gender domination, ecology, imperialism, and democracy. But, equally important, the latter now appear in another light—as struggles in, around, and, in some cases, against capitalism itself”. Rather than approaching resistance through discrete struggles, organizing around social reproduction could allow for a more expansive conception of revolutionary subjectivity, freed from the debate on value. What is at stake is not a simple sidestepping of the production process, but rather a more expansive conception of the ways in which capitalism structures class formation through and beyond the labour process.

Mai Taha is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). She has written on law, colonialism, labour movements, class and gender relations, and social reproduction in the Middle East. A selection of her publications include: Human Rights and Communist Internationalism: On Inji Aflatoun and the Surrealists (2023); The Comic and the Absurd: On Colonial Law in Revolutionary Palestine (2022); and Law, Class Struggle and Nervous Breakdowns (2021). Using film, literature, and oral history narratives, Mai is currently working on questions relating to labour, the home, and revolutionary subjectivity. This piece is based on her article, “Thinking through the Home: Work, Rent, and the Reproduction of Society,” (2023) published in Social Research: An International Quarterly, vol. 9, no. 4.

Notes:

- ↩ One example is the 1915 Glasgow rent strike and the Glasgow Women’s Housing Association.