Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

I have been in Caracas, Venezuela, for the past two weeks, before and after the presidential election on 28 July. In the run-up to the election, two things became clear to me. First, the Chavistas (supporters of Hugo Chávez and the Bolivarian project that is now led by President Nicolás Maduro) have the enormous advantage of an organised mass base. Second, knowing that the odds were not in their favour, the opposition, led by far-right María Corina Machado and the U.S. government, were already signalling defeat before the election even took place by alleging that it would be fraudulent. Since at least the 2004 recall referendum, when the opposition tried to remove Chávez from office, it has become a right-wing cliché that the electoral system in Venezuela is no longer fair.

Just after midnight on election night, July 28 (Chávez’s seventieth birth anniversary), the National Electoral Council (CNE) announced that, with 80% of the votes counted, there was an irreversible trend: Maduro had won re-election. These results were then validated a few days later by the CNE with 96.87% of the votes counted, showing that Maduro (51.95%) defeated the far-right candidate Edmundo González (43.18%) by 1,082,740 votes (the other opposition candidates received merely 600,936 votes combined, which means that even if the votes received by other opposition candidates had gone to González, he still would not have won). In other words, with 59.97% voter participation, Maduro received just over half of the votes.

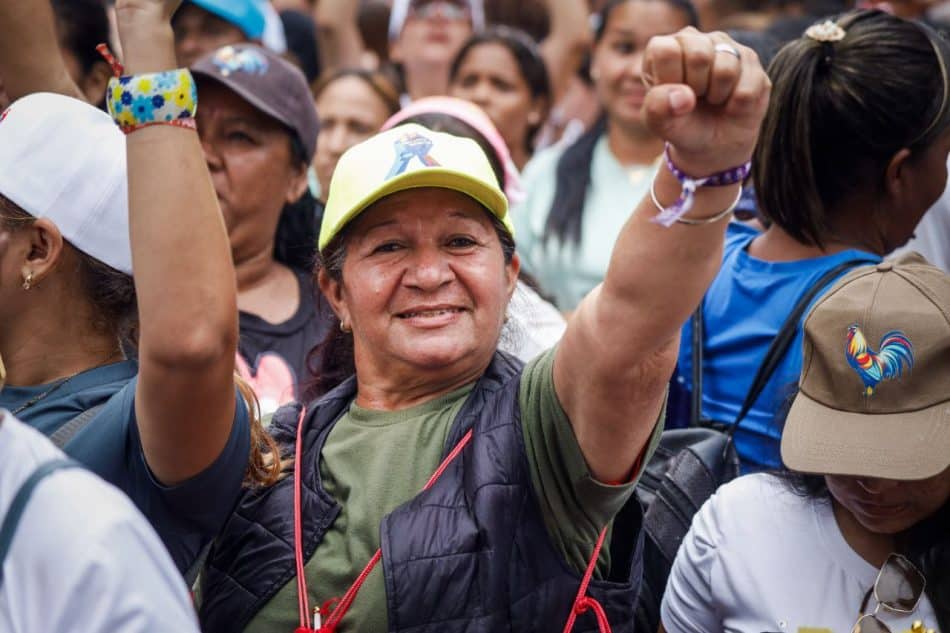

Credit: Zoe Alexandra

I talked to a high-level advisor to the opposition, who asked to remain anonymous, about the results. He said that, though he sympathised with the opposition’s frustration, he felt that the final result seemed about right. In 2013, he explained, Maduro won by 50.62%, while Henrique Capriles received 49.12% of the votes in the presidential elections that took place just over a month after Chávez’s death. This was before the oil prices collapsed, and before sanctions tightened. At that time, with Chávez gone, the opposition smelled blood, but they could not prevail. ‘It is hard to beat the Chavistas because they have both the programme of Chávez and the ability to mobilise their supporters to the ballot box’, he said.

It is not that the far right does not have a promise of social transformation; they want to privatise the state-owned oil company, return expropriated property to the oligarchy, and invite private capital to cannibalise Venezuela. Rather, it is that their promise of social transformation is at odds with the dreams of the majority. That is why the right cannot win, and that is why an important line of attack since 2004 has been to cry fraud.

Credit: Francisco Trías

And so, on election day, just after polls closed and before any official results had been released, Machado and Washington, as if in concert, began to bleat about fraud, building on a line of attack that they had been establishing for months. Machado’s followers immediately took to the streets and attacked symbols of Chavismo: schools and health centres in working-class areas, public bus stations and buses, offices of Chavista communes and parties, and statues of figures who had set the Bolivarian Revolution in motion (including a statue of Chávez as well as the Indigenous Chief Coromoto). At least two militants of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), Isabel Cirila Gil from Bolívar state and Mayauri Coromoto Silva Vilma from Aragua state, were assassinated in the aftermath of the election, two sergeants were killed, and other Chavistas, police, and officials were brutally beaten and captured.

It was clear by the nature of the attack that these far-right forces of a special kind wanted to erase the histories of Venezuela’s indígenas and zambos, as well as the working class and the peasantry. Every day since the election, hundreds of thousands of Chavistas have taken to the streets of Caracas and elsewhere. The pictures in this newsletter were taken by Francisco Trías at the 2 August Women’s March, by Zoe Alexandra (Peoples Dispatch) at the 31 July March of the Working Class in Defence of the Homeland (two of many mass mobilisations that have taken place since the elections), and by me at a pre-election rally on 27 July. In each of these marches, the chant no volverán—they will not return—reverberated amongst the crowd. The oligarchy, they said, will not return.

Credit: Vijay Prashad

The Bolivarian Revolution began in 1999, when Chávez ascended to the presidency. Waves of elections were held to change the constitution and overcome the oligarchy’s resistance (as well as that of Washington, which has tried many times to overthrow Chávez, such as the failed coup d’état in 2002, and Maduro, such as the ongoing use of sanctions as a tool for regime change and attempts to invade the Venezuelan border). Chávez’s government nationalised the oil industry, renegotiated rent prices (through the 2001 Hydrocarbons Law), and removed the layer of corrupt officialdom from the spigot of national profits.

The national treasury was able to earn a greater percentage of royalties from multinational oil firms. The stated-owned oil company Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) set up the Fund for Social and Economic Development (Fondespa) to finance schemes benefitting oil workers, their communities, and other projects. The oil wealth was to be used to industrialise the country and to halt Venezuela’s dependency on its oil sales and on imports. Diversifying the economy is a key part of the Bolivarian agenda, including reviving the country’s agriculture, and in so doing working to meet the fifth strategic objective of The Plan for the Homeland to ‘preserve life on the planet and save the human species’.

Credit: Francisco Trías

It was because of that oil money that Chávez’s government could increase social spending by 61% ($772 billion), which it used to uplift the lives of the population through large-scale programmes such as various misiones (missions) that set out to make the rights enshrined in the 1999 Constitution a reality. For example, in 2003 the government set up three missions (Robinson, Ribas, and Sucre) to send educators into low-income areas to provide free literacy and higher education courses. Mission Zamora took in hand the process of land reform, and Mission Vuelta al Campo sought to encourage people to return to the countryside from urban slums. Mission Mercal provided low-cost, high-quality food to help wean the population off highly processed imported foodstuffs, while the Mission Barrio Adentro sought to provide low-cost, high-quality medical care to the working class and poor and Mission Vivienda built more than 5 million homes.

Through these missions, poverty rates in Venezuela declined by 37.6% from 1999 to the present (the decline of extreme poverty is stunning: from 16.6% in 1999 to 7% in 2011, a 57.8% decline, and if you begin measuring from 2004—the start of the missions’ impact—extreme poverty declines by 70%). Venezuela, one of the harshest unequal social orders prior to 1999, became one of the least unequal societies, with the Gini coefficient dropping by 54% (the lowest in the region), indicating the impact that these basic social policies have had on everyday life.

Credit: Francisco Trías

Over the past twenty years, during my frequent stays in Venezuela, I have spoken with hundreds of working-class Chavistas—many of them Black women. Since the tightening of the sanctions, Venezuelans have faced immense privations and freely proffered their complaints about the direction of the revolution. They do not deny the problems, but unlike the opposition, they understand that the root of the crisis is the U.S. hybrid war. Even if there is increased social inequality and corruption, they locate these ills in the violence of the sanctions policy (which even the Washington Post now admits).

During the massive marches to defend the government in the week following the elections, people openly described the two choices that faced them: to try and advance the Bolivarian process through Maduro’s government or to return to February 1989 when Carlos Andrés Pérez imposed the IMF-crafted economic agenda known as the paquetazo (packet) on the country. Pérez did this against his own election promises and against his own party (Acción Democrática), provoking an urban rebellion known as the Caracazo in which as many as 5,000 people were killed by government forces in one fateful day (though death toll estimates vary widely).

Credit: Francisco Trías

Indeed, many feel that Machado would usher in an even worse era in the country, since she has none of the social democratic finesse of Pérez and would like to inflict shock therapy on her own country to benefit her own class. A popular Venezuelan saying captures the essence of this choice: chivo que se devuelve se ’esnuca (the goat that returns breaks its neck).

Canadian billionaire Peter Munk, who owned Barrick Gold, wrote that Chávez was a ‘dangerous dictator’, compared him to Hitler, and called for him to be overthrown. This was in 2007 when Munk was upset because Chávez wanted to control Venezuela’s gold exports. The general orientation of the Chávez government was to ‘delink’ from the global economy, which meant preventing multinational firms and powerful countries in the Global North from setting the agenda of countries such as Venezuela.

This idea of ‘delinking’ is the main focus of our latest dossier, How Latin America Can Delink from Imperialism. Building upon the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America—Peoples’ Trade Treaty (ALBA-TCP) 2030 Strategic Agenda, the dossier proposes four key areas that must be delinked in order to set the foundation for a sovereign development strategy: finance, trade, strategic resources, and logistical infrastructure. This is precisely what the Bolivarian process has set out to do, which is precisely why its government has been so harshly attacked by U.S. imperialism and by multinational corporations such as Barrick Gold.

Credit: Zoe Alexandra

On the day after the election, it rained. At one of the marches to defend the Bolivarian process that day, a Chavista recited a few lines from a 1961 poem by the Venezuelan poet Víctor ‘El Chino’ Valera Mora (1935—1984), ‘Maravilloso país en movimiento’ (Marvellous Country in Motion).

Marvellous country in motion

Where everything advances or retreats

Where yesterday is a push forward or a farewell.Those who don’t know you

Will say that you are an impossible quarrel.So frequently mocked

Yet always standing upright with joy.You will be free.

If the condemned do not reach your shores

You will go to them another day.I keep believing in you

marvellous country in motion.

Warmly,

Vijay