Colonialism and Capitalism: Canada’s Origins, 1500-1890

Bryan D. Palmer, a long-time contributor to Canadian Dimension, and one of Canada’s leading historians of labour and the left, has written a bold, wide-ranging interpretation of the country’s history. In two volumes to be published in October 2024 and May 2025—Colonialism and Capitalism: Canada’s Origins, 1500-1890 and Capitalism and Colonialism: The Making of Modern Canada, 1890-2025—Palmer places the accent on Canada’s entwined colonial and capitalist development. These two structures of determination are not separable, he argues, but intricately embedded in one another, and have been for centuries.

This challenging and illuminating account is truly a new history for the twenty-first century, one that lays out how the country’s past lies before us, demanding redress. The two books that comprise this retelling of Canada’s rise from a colony to a nation that has routinely and relentlessly colonized, should and will be widely read by all concerned with basic issues of social justice.

Based on an impressive command of scholarly literature as well as a familiarity with activist writing, Palmer’s reassessment of the making of Canada is written with panache and a prose as accessible as it is engaging, Old and tired mythologies of Canada as a “peaceable kingdom” are laid to waste, as are misrepresentations of the acquiescence of the oppressed and exploited. Palmer highlights how colonialism and capitalism, as the two overarching influences in the development of Canada as a nation state, have given rise to resistance. The struggles of Indigenous peoples and many others, including the Québécois and the working class, are never sidelined in this important and timely study.

A master storyteller who combines meticulous scholarship with engagement with the political issues of our times and their deep roots in the history of Canada, Palmer explores the many dimensions of conquest and inequality, poverty and plunder, that are the sordid underside of Canadian nation building and state formation and the individual riches and corporate fortunes accruing from the profit system.

At the foundation of a regime of accumulation reaching back centuries is the dispossession of those diverse First Nations inhabiting the vast geographical reaches of what now constitutes Canada. Their political economy of “the dish with one spoon” stood in stark contrast to the sanctity of private property and the animating ideology of possessive individualism that constituted core components of the rising materialist ethos that was emerging as European societies transitioned from feudalism to capitalism and embarked on empire’s project of colonization.

Colonialism and Capitalism: Canada’s Origins, 1500-1890 ends with a chapter on “The Tragedy of the 1880s.” Canadian Dimension excerpts a section of this chapter, in which Palmer lays out how the anti-colonial struggles of Indigenous peoples, epitomized in the 1885 War of Resistance in the Canadian North-West, occurred at precisely the same time as the first “Great Upheaval” of the Canadian working class, centred in the manufacturing heartland of Ontario and Québéc, erupted.

The legacy of the failure of these two mobilizations of resistance to coalesce remains with us still, a conundrum for the contemporary left. How can it bring together the anti-colonial struggles of Indigenous peoples and the potentially anti-capitalist opposition of the working class? How can the hegemonic hold that both colonialism and capitalism exercise among the broad masses of Canadian society, be their wages high or low, whatever the complexion of their skins and the character of their identities, be transcended?

Columbia University anthropologist and professor Audra Simpson, author of Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States (2014), offered the following praise of Palmer’s groundbreaking new work:

Colonialism and Capitalism: Canada’s Origins, 1500-1890 is what we have been waiting for, a history that links the material and ideological conditions of state-making to the centrality of Indigenous dispossession. Palmer offers an expansive and exhaustive overview of the inextricable relation of colonialism and capital accumulation. The ways in which race, class, and gender featured in the varied subordinations critical to bringing Canada as a nation state into being, and giving rise to many and varied forms of resistance, are given careful and nuanced consideration. This is a much-needed origin story.

Canadian Dimension reprints this concluding passage to the first of Palmer’s two volumes in the hopes that readers will read his reinterpretation of Canadian history and take its account of the country’s past into consideration in their ongoing struggles.

The tragedy of the 1880s

If 1885 and its war of resistance constituted colonialism’s crisis, 1886 witnessed capitalism’s most significant class challenge. The “Great Upheaval” culminated in a rash of mass strikes and local trade union conflicts, Knights of Labor and union label campaigns, and Provincial Workmen’s Association and nascent independent labour party forays into political activism. The people stood poised against monopolistic power and political rings; and “union” seemed the rallying cry of the hour, not only in Toronto but in Prince Albert. It was enough to cause colonizers and capitalists, powerbrokers and patricians, and Canada Firsters and Fathers of Confederation to shudder. Macdonald was right to worry. Steering the ship of state so that it could navigate in the interests of Confederation’s commitment to colonialism and capitalism was proving anything but easy.

Yet Macdonald and others managed to weather stormy seas. One reason for this was that the two uprisings and upheavals of the 1880s never managed to decisively connect with one another. The oppositions of 1885 and 1886 seemed to arise out of different worlds, being enacted on stages of unlike constructions. There were of course divergences separating St. Laurent and St. Catharines. Canada’s history of uneven capitalist development combined with its historically evolving colonialism to structure the meanings of protest in 1885 and 1886 differentially. Nonetheless, the struggles of settlers in Prince Albert, Indigenous peoples and Métis communities, trade unionists, Knights of Labor, and Provincial Workmen from Springhill to Hamilton to Victoria, shared a great deal. They were often directed, for instance, against a common enemy: concentrated capital and its relentless appetite for accumulation. The language of attack, aimed forcefully at oligarchies and cabals, resonated across lines of difference in a commonality of position as relevant in the North-West as it was in the factory cities and mill towns of Ontario or the coal mining communities of Cape Breton.

Phillips Thompson, the Toronto-based radical journalist, pioneering Canadian socialist, and resolute advocate of “labour reform,” declared unequivocally in 1886: “Capitalism is king. The real rulers are not the puppet princes and jumping-jack statesmen who strut their little hour upon the world’s stage, but the money kings, railroad presidents, and great international speculators and adventurers who control the money-market and the highways of commerce.” Thompson’s conclusion that “of all the forms of monopoly, the most oppressive and the most insidious is that of private land ownership” would have been embraced by William Henry Jackson and, perhaps, Gabriel Dumont. Statements like, “The great truth that the land belongs of right to the whole community, and that any claim on the part of an individual to more than a right of occupancy or cultivation … is robbery,” coincided with traditional Indigenous and Métis understandings and practices. Thompson’s insistence that “destitution and semi-starvation” existed because of “the edict of the government—the real ‘government’ of capitalism” certainly related directly to the experience of First Nations peoples and Métis settlements suffering hunger and want in the 1870s and 1880s, as well as to urban proletarian neighbourhoods in central Canada and Montréal, be they Irish or Québécois.

There were faint suggestions that disparate struggles might coalesce. First Nations and Métis anti-colonial stands, the protests of organized labour, and the emerging workers movement’s struggles for better pay, conditions, and control over the work process did, at times, hint at more than a shared chronology of conflict in the 1880s. To be sure, labour’s uprising rarely espoused an unequivocal anti-capitalism to the same extent that the Métis-led war of resistance in the North-West categorically rejected colonialism. There were some faint indications, however, that both challenges to capitalism and colonialism were nonetheless gravitating in directions that might feed into common struggles. Broad united fronts of resistance and refusal, posed resolutely against the entwined nature of these two deep structures of subordination and exploitation, were recognized by a far-seeing few as what was required.

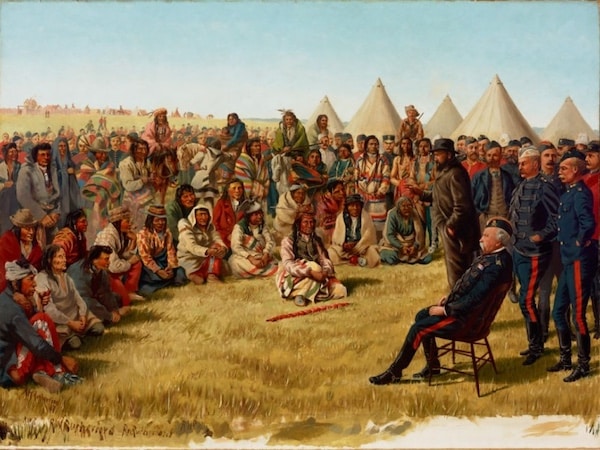

“The Battle of Cut Knife Creek.” Lithograph from The Canadian Pictorial and Illustrated War News, 1885. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

When the Grand Trunk engineers struck in 1877, militia aid to the civil power was enlisted to quell the threat to public order. Constituted authority feared that even this intervention would prove inadequate because of so-called communist subversives (who of course did not, for the most part, exist). One of only two militiamen who risked $20 fines in refusing to turn out and defend the peace was an “Indian.” In British Columbia, especially, Indigenous people well acquainted with waged work, labour stoppages, and the necessity of solidarity were described fearfully in 1885 by the province’s first chief justice, Matthew Baillie Begbie. He saw these people as “Indians,” to be sure, but also as a race of laborious independent workers. They were well on their way to embracing trade union militancy, appreciating the necessity of collective workplace action. This grew out of the recognition, in the later words of the Squamish/ Skwxwū7mesh Úxwumixw longshore worker, Mathias Joseph “A long time ago, the Indians depended on hunting and fishing as their only means of living. Now things have changed.”

Those changes prompted “race traitors” like William Henry Jackson and James A. Teit to embrace and defend Indigenous traditions, situating them at the crossroads of resistance, anti-colonialism, and the anti-capitalist political economy of socialism and labour reform. The militarism that fused with Canadian nationality in the suppression of the war of resistance in the North-West was not universally applauded in central Canada. Reform circles offered voices of repudiation. The bellicose jingoism of 1885—86 was opposed by Knights of Labor newspapers, among them Hamilton’s Palladium of Labor. Phillips Thompson, predictably, embraced the Métis-led revolt. Repulsed by the “Bloody Assize” at Regina, Riel’s execution would, Thompson insisted, bring shame upon the young Dominion of Canada. He defended the Métis and First Nations who took up arms against their oppressors. Thompson saw them as righteous combatants, leaders of a people’s struggle against “spoliation at the hands of land grabbers and rascally government agents.” Riel himself penned an appeal to labour reform and anti-colonial circles in the United States, writing to Patrick Ford’s New York Irish World in 1885. He complained that after solemn promises by the Canadian government guaranteeing Métis entitlements to their territory in the North-West, these rights were “torn from us and given to land grabbers, who have never seen the country.”

Notwithstanding these kinds of suggestive links, the 1880s did not see an alignment of the dual challenges to the oppressive colonial state and exploitative capital. The possibility of a coming together of forces resisting colonialism and moving towards a working-class anti-capitalism succumbed to a series of powerful and well-honed attacks. They were many and varied, orchestrated by the state and conservative political and business interests. Sustaining this campaign of capitalists and colonizers were the initiatives of the institutional state, dedicated to the political maintenance of the profit system and the imperial project that nurtured and was now inseparable from it. If this was not enough, there was always the armed might of the nation, grown increasingly refined in its military organization and sophisticated weaponry over the course of the nineteenth century.

Richard J. Kerrigan, a Montréal labour activist who began as a Knight of Labor, joined the Socialist Labor Party, and ended up in the 1920s in the One Big Union movement, wrote of the “dynamic year of 1886.” It was a formative moment in the making of Canada, when state repression, anti-Knight of Labor pronouncements from the Catholic Church, and a host of other issues flowed together in an avalanche of reaction. The end result was the demoralization of the nascent movement of workers’ opposition. Its demise was not unrelated to the defeat of the armed dissidents of the North-West: “So with Home Rule, land thievery, CP Ry scandals, Louis Riel, National Policy, Jesuit machinations, etc., etc., as issues the electorate would have been hogs for misfortune had they not had some reason to vote for or against the Conservative government,” Kerrigan wrote in 1927. He concluded with the benefit of hindsight:

The Labor issue was linked up with the Liberal and the Tory, and had its throat cut accordingly.

In this tragic severing of a possible fusion of the anti-colonial and potentially anti-capitalist working-class struggles of the 1880s lies a measure of the legacy of division and difficulty willed to twentieth-century radicalism and its varieties of anti-colonial/anti-capitalist dissent. Each of the currents of challenging thought and active struggle associated with the war of resistance of 1885 and the Great Upheaval of 1886 was weakened without benefit of the strengths of the other. The insurrectionary resolve that arose out of conditions in the North-West needed the emerging political economy of capitalist critique, generated within the organized workers’ movement, evolving out of the experience of industrial workplaces, and conceptualized among “brainworkers” like Phillips Thompson. The labour reform movement that peaked in the 1880s, however, also needed to enhance its understandings of the dispossession of colonized peoples, stake out an uncompromising opposition to the state-capital coupling, and commit its considerable resources and personnel to struggles that lived up to its organizing principle, “An injury to one is an injury to all.” This truly was the corollary of “the dish with one spoon.”

Hamilton’s Knights of Labor parading down King Street, 1885. Photo courtesy Library and Archives Canada/PA-103086.

In failing to bring these congruent, oppositional traditions into a more connected and common struggle in the 1880s, both streams of dissent and protest were enfeebled. The historic structures of colonialism and capitalism, and their advocates, were empowered. Interests of “race” and “nation” too often supplanted the potential and common struggles of “class,” and its often reciprocal relationship with gender, region, and other identities increasingly associated with subordination. The difficulty we have, a century and more later, in grasping what was missed in this road not taken is itself a reflection of what was repressed and lost, as well as what had been validated and vindicated, in the promise, possibility, and passing of 1885—1886.

Possibilities not grasped as the nineteenth century closed would, over the course of Canada’s next century and a half, resurface. First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples continued to confront the dispossession so central in Confederation’s capitalist making. In this long history from 1890 to the present, colonialism continued unabated, enhancing its containment of Indigenous peoples before the state was forced to adopt a rhetoric of recognition and reconciliation. Capitalism played its role in this political economy of placation, willing to appease some elements of Indigenous communities with the largesse of revenues accruing from resource extraction. That same capitalism was forced to bend in its recalcitrance toward organized labour, conceding in the mid-twentieth century the kinds of collective bargaining rights that it steadfastly refused to countenance in many a nineteenth- and early twentieth-century struggle. Then, amidst a new crisis for capital and the fiscal restraints it imposed on the state in the 1970s, an epoch of austerity and a revival of the anti-labour stands adopted almost universally by nineteenth-century capital led to an intensified class war waged from above. As the twentieth century gave way to the twenty-first, this left workers and their unions beleaguered, wages eroded, and jobs increasingly insecure. Capital seized the initiative and continued processes underway since the late nineteenth century, accelerating in the early twenty-first century years of increasingly concentrated corporate power.

Colonialism and capitalism, as legacies, as well as organized systems of overwhelming influence within the political economy of Canadian governance and the unfolding of everyday life, thus continue to exercise a profound impact in our current times, and not always for the better. The dilemma of a fractured opposition, in which the forces opposed to colonialism and capitalism have never quite managed to mount a coordinated campaign of resistance, remains as potent a division in 2025 as was the case in earlier times, especially the 1880s. Over the course of the 135 years from 1890 to 2025, Indigenous peoples, as well as many Québécois, workers, and their allies, confronted capitalism and colonialism in many and varied ways. Yet the times when diverse struggles of the broad masses of these dispossessed constituencies came together in recognition that the colonialism/capitalism entanglement was a common enemy, demanding a united front of opposition, were nonetheless quite rare.

This is the story that links this volume, Colonialism and Capitalism: Canada’s Origins 1500-1890 to its sequel, Capitalism and Colonialism: The Making of Modern Canada, 1890—2025. Together these related volumes, always conceived as one study, constitute a new history of Canada, one written out of the concerns of the twenty-first century. Our times are ones that make it impossible to bury either the past of Indigenous People’s dispossession, as so many earlier histories of Canada once did. Equally difficult to ignore or overstate is the extent to which that history of appropriation and subordination is and historically has been intricately related to the rise of capitalism and the extent to which this system of accumulation generated, extended, and intensified all manner of inequalities.

Canada’s making as a modern nation-state took place, then, at the interface of colonialism and capitalism. Addressing the entwined history of these related structures of determination is central to understanding how Canada and Canadians came into being. Where a nation and its peoples have gone and how they travelled in particular directions, not only in past times but into the present, can only be understood through engaging with colonialism and capitalism as cornerstones of all things Canada. What the future holds, similarly, can only be discerned by coming to grips with Canada’s colonial and capitalist history. As a new history written out of the concerns of the twenty-first century, Colonialism and Capitalism has presented a past that is now before us. In Capitalism and Colonialism, Canada’s making as a modern nation is explored in an ongoing discussion of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The legacies of the nation’s beginnings in the centuries reaching from 1500 to 1890 continue to reverberate in the changed context of capitalism’s restructuring and colonialism’s continuities and extensions.

Taken together these volumes explore a Canadian past that obviously conditions the country’s present, but does not necessarily have to continue to determine the future. What lies before us is not only what has gone on for centuries, but an obligation: to build alternatives to the many debilitating consequences that colonialism and capitalism—the entwined, reciprocal organizational imperatives behind Canada’s making—have produced and continue to reproduce. Their engines of relentless dispossession and predatory accumulation inevitably engender exploitation and economic crisis, inequality and oppression, concentrated power/property, and ecological disfigurement if not destruction. Canadians need not be confined in the shapes that colonialism and capitalism have hammered out for them, over centuries, on an anvil of developmental determination. Paths once taken can be reversed; choices made in different contexts must, and are able to be, rethought and revisited; changes advocated and refused might now well be embraced, adapted to new circumstances. And struggles long separated from one another can be brought into new and exhilarating alignment. A better Canada might well then be in birth.

Bryan D. Palmer, a long-time contributor to Canadian Dimension, is an historian of labour and the left.