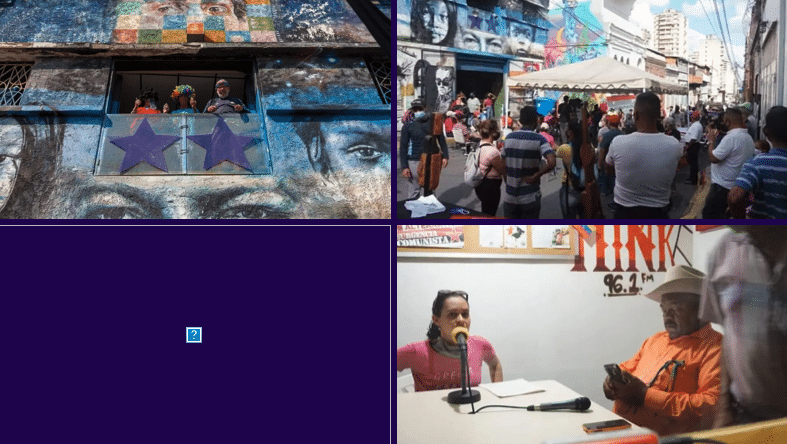

La Minka collective is based in a multi-use cultural space near Miraflores presidential palace in the west of Caracas. Outside the building, a former printing press, is a colorful mural covering its three-story facade that represents different aspects of Venezuela’s popular history. Inside there is an array of rooms dedicated to teaching, theater, and music, along with a radio studio and a community kitchen.

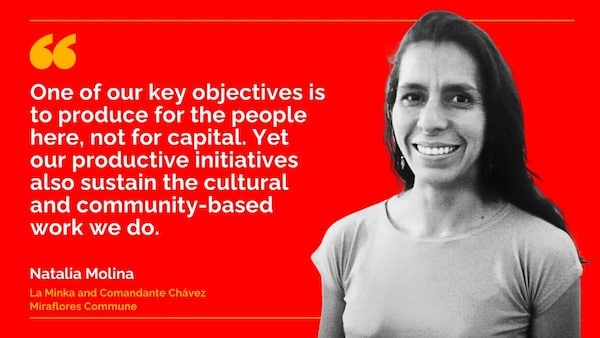

“Minka” or “Minga” is a Kichwa word meaning community work. True to this idea, La Minka collective has reached out to the community with its cultural projects. It also defends grassroots democracy, taking all major decisions in assembly. Now La Minka collective is working to foster a socialist commune in its neighborhood. In this interview, Natalia Molina, a founder of the organization, talks about the origins of the project and its objectives, and about the defense of the Bolivarian Process in the context of the post-July 28th fascist attacks.

Cira Pascual Marquina: Can you introduce us to the history and objectives of La Minka collective?

Natalia Molina: La Minka is a revolutionary collective focused on promoting comprehensive community work. Inspired by Hugo Chávez, La Minka was founded twelve years ago with a view to advancing toward communal self-governance.

We are a collective that works in diverse spheres: we promote cultural, educational, communicational, and productive initiatives. All these projects are interlinked in building a world without oppression and domination.

La Minka is part of Comunidades Al Mando-Proyecto Nuestra América [CAM-PNA, Communities in Command-Our America Project]. CAM-PNA is a kind of parent organization that guides us in developing our political strategies. However, each project within the larger organization evolves according to its unique characteristics and its people.

One of our strengths is cultural work. We view art, culture, sports, and communication as pathways to transforming collective consciousness. We aim to build a decolonized and non-capitalist society. This vision is embodied in the work we do promoting the Comandante Chávez Miraflores Commune.

Cira Pascual Marquina: What is Proyecto Nuestra América? Where does it come from?

NM: Proyecto Nuestra América is a continental movement within the “historical current,” a broad coalition based on the idea that we struggle along a path laid out by our ancestors because they, like us, fought for emancipation. For us, class struggle brings all the oppressed and exploited together, past and present, here and all around the continent.

Our history comprises Afro-Indigenous struggles, the stories of those who have been made visible in the history books, and the stories of those who were made invisible. Proyecto Nuestra América is part of this long history. For us, the struggles of the past and the struggles of the present are not only linked—they are one and the same!

CPM: Kasa La Minka is a cultural hub in Caracas. It has a beautiful headquarters in which, at any given moment, capoeira and yoga classes, radio production, and community assemblies might be taking place simultaneously. Can you tell us more about this space?

NM: In 2012 the Culture Ministry turned over the building that we now know as Kasa La Minka to a group of cultural collectives organized in the working-class barrios of Caracas. Those were the times of a grassroots campaign for Chávez’s reelection called “la cayapaña” [a coinage based on two words: “cayapa”—the practice of working together—and “campaña” or campaign]. Today, Chávez’s spirit runs deep in our organization: he inspired us then, and he continues to inspire us now.

CPM: La Minka has helped to organize the Comandante Chávez Miraflores Commune. Can you explain that initiative?

NM: Since the early days of La Minka, one of our main objectives has been to promote communal self-government. We have always worked hand in hand with the communal councils near us.

The Comandante Chávez Miraflores Commune was founded in 2019. It was a beautiful project, because it helped us get closer to the community. The first thing we did was to promote a popular school that took the name of Simón Rodríguez [Venezuelan pedagogue and philosopher of the early 19th Century]. There we organized workshops about communal organization and production, how the communal parliament operates, etc. We debated both the big picture and the details of a commune.

Through a participatory process led by the community, we also began to collect testimonies about the barrio’s history. Together we reconstructed the history of the barrio. We learned who was here before the invaders and even about the specters that inhabit our community. Simply looking at the first map of Caracas, we learned that our community was right on the border of the old city.

Those were the early days of the commune; it was really wonderful. Now the commune is actively addressing problems such as water supply, healthcare, education, or security, and organizing “street parliament” events in which government spokespeople come to our commune to discuss the historical moment with us.

At the Miraflores Commune, Chávez’s spirit is alive and well!

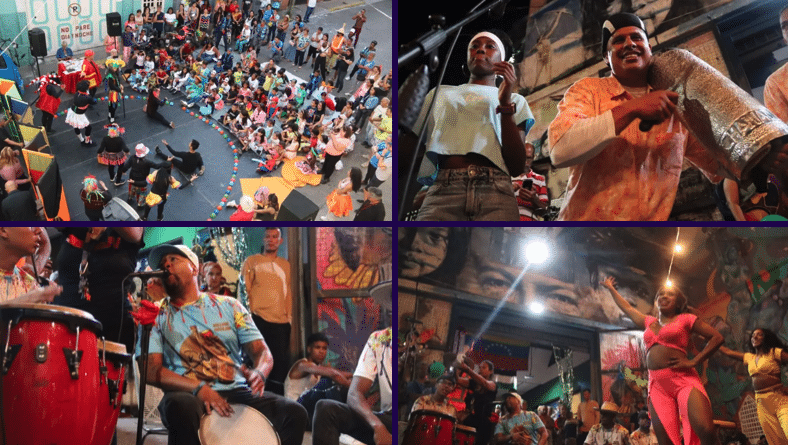

CPM: La Minka is best known for its cultural work. What specific cultural and artistic activities do you promote out of the Kasa La Minka multi-space?

NM: Since its early days, La Minka has been very committed to Capoeira [an Afro-Brazilian martial art that blends dance with self-defense]. However, we also organize circus sessions, street theater, as well as dance and music events.

As a whole, Venezuela’s cultural traditions are highly important to us. Every year we organize the “Cruz de Mayo” [communities gather around a cross dressed with flowers to sing and dance], the “Velorio de San Juan” [Afro-Venezuelan tradition honoring John the Baptist with drums, songs, and dances], carnival “parrandas” [street parades], etc. Our cultural heritage is alive and we are part of it.

But our work reaches beyond cultural production. We also bake bread, maintain an agroecological vegetable garden, and run a soup kitchen that feeds some 100 people every day.

CPM: I understand that La Minka’s productive projects are crucial for sustaining the cultural and community work that you do.

NM: Absolutely. One of our key objectives is to produce for the people here, not for capital. Yet our productive initiatives also sustain the cultural and community-based work we do. Our first project was doing silk screening. We did it in a very simple, homemade way.

Later, comrades from sister organizations who were running bakeries taught us the craft of bread-making. Soon after, we acquired some basic equipment and began making “boleado” [round bread] at Kasa La Minka. This was around 2016 when people we struggling to find even the most basic staples. It was before the government’s CLAP [subsidized food distribution] initiative, so we focused on a distribution plan within the community to ensure access.

That was the time when there were endless queues outside bakeries. The government would provide bakers with sacks of flour at subsidized prices for bread production. However, instead of baking bread, they would make sweets or re-sell the flour on the side at higher prices. In effect, they had launched a “bread war” against the pueblo.

During this period, there was a bakery at a strategic spot at the entrance to our commune that was heavily involved in the “bread war” against our community. Despite repeated reports and fines, they produced only a small amount of bread each day, forcing people, many of whom were elderly, to endure long lines, and often mistreating them in the process.

There were also complaints about price gouging. Additionally, there were hygiene concerns and some workers filed labor-related complaints. As a result, the government repeatedly intervened in the bakery: it would be fined, shut down for three days, and then reopen…

Around that time, comrades from Comunidades Al Mando had proposed that the local government allow organized communities to take over sanctioned bakeries. Eventually, after this particular bakery’s umpteenth intervention, local government officials approached us and asked us to run the bakery for three months. Those three months have turned into seven years!

When we took over, we found 300 sacks of flour, with about 90 of them already expired! That showed us that the former owners had plenty of raw material to make bread. Yet they kept people waiting in long lines while claiming that the government wasn’t supplying them with flour.

I remember that when the government intervened in the bakery, there was a huge line outside, but plenty of bread was found in the back room. The owner’s aim was to make people suffer. Bread was their weapon in the war.

By the time we took over the bakery, the CLAP program was already in place, so we began producing bread exclusively for 18 local [CLAP] committees, ensuring fair distribution within the bakery’s vicinity.

Today the bakery, now known everywhere as “Panadería La Minka,” continues to make bread for the community.

CPM: That’s impressive! It’s great that the bakery is now working for the community. As I understand, the former owner won’t leave the self-managed bakery alone. He continues to harass “Panaderia La Minka.”

NM: Indeed, while the government is on our side because they know that our work is community-based, the bakery has been attacked over and over. We have received court orders from judges who were bribed by the former owner, while his goons and rogue police have come into the bakery with rifles. Still, we are not giving up!

CPM: The bakery is important for La Minka. Even so, could we say that it’s simply part of a larger strategic project for the collective?

NM: Indeed. The bakery is an important productive initiative for us, in part because it builds community. Additionally, the surplus helps us support the commune, promote our cultural and agroecological projects, and run our soup kitchen.

CPM: Can you talk about La Minka’s approach to community self-defense and safety?

NM: Our approach to defense is rooted in a well-structured contingency plan that identifies potential threats and critical issues long before they become emergencies. This strategy ensures that we are prepared for any situation, while allowing us to strengthen our organizational dynamics.

For instance, in the area of food security, we’ve carefully mapped out the community’s needs and identified the main distribution routes. We’ve also analyzed the local power grid and secured a generator to use during potential blackouts, like the one we experienced last week.

Additionally, we’ve done a study of the health situation of our community. As a result, we know where doctors, nurses, and medical supplies are located. Finally, we’ve studied the transportation and water distribution systems in the community.

This approach enables us to respond to emergencies not with mere instinct, but with well-coordinated and effective strategies.

CPM: Both Kasa La Minka and Panadería La Minka are very close to Miraflores Presidential Palace. Since the latter is often the focus of attempts to destabilize the government, your grassroots defense work must also have a strategic dimension.

NM: Absolutely. We are situated right in the epicenter of political power in Venezuela, just a stone’s throw away from the house where Chávez lived, which is a sacred space for us. Our location is indeed strategic, and with that comes a significant responsibility!

CPM: Along those lines, there was a recent attack on Panadería La Minka, and it occurred just after the presidential elections. What exactly happened?

NM: The attack on the bakery by fascist groups didn’t surprise us. It was anticipated that they might do this, and it wasn’t the first time the bakery had been attacked. But usually we are able to fend off these aggressions using our weapons of choice: drums, songs, and our unyielding spirit. However, this time, the attack was more violent, forcing us to call on sister organizations and even public security forces to help repel them.

But the attack wasn’t just aimed at the bakery; it was an assault on the entire community. Why? Because we are a grassroots Chavista organization and our commune is the gateway to Miraflores Palace. If the fascists had succeeded in taking over the bakery and photographed themselves there, they would have sent a clear message: “We’re on the doorstep of Miraflores. The president should be worried!”

Of course, we would never allow that to happen!