A revolutionary process affects all spheres of life, from national politics to grassroots organization, from work to leisure, from healthcare and education to science. In this interview, Ximena González Broquen, a social scientist heading up a center in Venezuela’s prestigious Institute for Scientific Research [IVIC], and the compiler of several essay collections, discusses the Ethics of Liberation as a framework that challenges the top-down, market-driven logic of conventional scientific research institutes. She advocates for a more democratic research environment while aiming to build bridges with organized communities.

Cira Pascual Marquina: As a researcher, you work with an Ethics of Liberation that aligns with decolonial and anti-capitalist perspectives. What is the Ethics of Liberation?

Ximena González Broquen: Enrique Dussel’s Ethics of Liberation is central to my perspective regarding research and knowledge production. The idea is that life must be prioritized above all else—ours is an ethics for life applied to research.

When it comes to knowledge production, the Ethics of Liberation has a strong political component. In his reflection, Dussel lays out a path to liberation that starts with the awareness of being oppressed, moves through the desire to dismantle systems of oppression, and then culminates in the will to build a new system.

This ethics applies to all spheres of life, including research, and it represents a pedagogy of liberation. In scientific terms, it’s different from bioethics, which focuses on isolated health and biological issues. The Ethics of Liberation emphasizes that actions—and research—must align with the struggle for collective life. Our ethics are about recognizing the collective self and being conscious of transformations happening around us.

CPM: This brings up a fundamental question: how is knowledge constructed in a capitalist, colonial, or neo-colonial context?

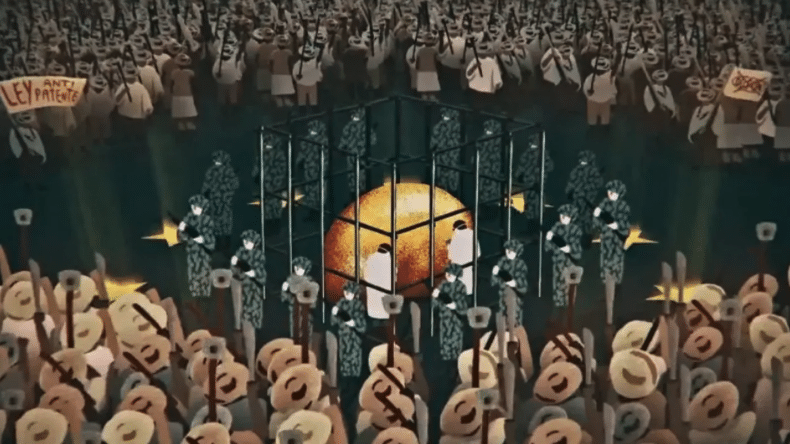

XGB: In the Ethics of Liberation, the collective dimension of knowledge construction is crucial. This contrasts sharply with how conventional science typically operates. The dominant model envisions science as the work of an isolated individual—a lone genius making discoveries in a lab. These discoveries are then patented and enter the commercial system, which is understood to be the only valid means of knowledge circulation.

On the other hand, from the standpoint of the Ethics of Liberation, knowledge construction starts with acknowledging the varied ways oppression impacts us. This awareness forms a foundation for co-constructing knowledge in dialogue with others, challenging the hierarchical organization of science as we know it today. It shifts the focus from individual to collective knowledge production.

An illustration of how intellectual property works in a capitalist society. (Semillas del Pueblo)

CPM: How does this paradigm shift affect the organization of research?

XGB: When thinking about science and research through the Ethics of Liberation, we must dismantle the hierarchical structure that underpins conventional research institutions.

At IVIC’s Center for the Research of Social Transformations, we’ve been working towards this goal for over twelve years. Our center strives to foster the collective construction of knowledge through diverse dynamics, processes, and projects. This may sound easy, but it’s a real challenge because we’ve been trained to research within a hierarchical framework, but we aim to build truly collaborative projects.

And by “collaborative,” I don’t just mean collaboration inside the scientific community. We need to work with the real actors and within the realities we aim to transform. From the Ethics of Liberation perspective, knowledge should be deployed to transform the world, not just observe it. This goes against the isolationist organization of the existing scientific system, which restricts the creation of knowledge to a few privileged individuals, often exploiting those below them in the academic hierarchy, as well as the people whose knowledge is extracted via fieldwork and other mechanisms.

In our center, we aim to not only help transform the world but to change our scientific community. We believe in science but also think it must be radically transformed. Part of this involves reclaiming our role as researchers. The scientific community is key to the political transformation of the world, and it is also our home.

CPM: How does the dominant scientific system extract knowledge? What mechanisms does it use?

XGB: The example of seeds illustrates this very well. The modern seed production system relies on biotechnology to modify and patent seeds, which are then sold through the market. While the privatization of seeds happens through patents, it’s crucial to understand that scientists aren’t truly “creating” these seeds. Seeds originate from centuries of knowledge passed down from generation to generation in campesino and Indigenous communities.

What often happens is that a scientist goes to the field, talks to campesinos, takes a few seed samples, brings them to the lab, and makes a few modifications—some of which may be beneficial, though GMO modifications are harmful. The scientist then claims the seed as their own creation, ignoring the centuries of work and knowledge embedded in that seed.

This pattern of extraction also exists in the social sciences. A researcher may visit a community, collect stories and reflections, and publish articles presenting these ideas as their own. This repackaging in scientific language is a form of extraction.

CPM: You mentioned the Center for the Research of Social Transformations at IVIC. What are the center’s objectives?

XGB: The center was founded in 2012 as part of the IVIC, the country’s leading scientific institution. However, our vision differs significantly from the rest of the institution: our objective is to research socio-political transformation processes in Venezuela, the region, and the world from the perspective of the Ethics of Liberation, Liberation Politics, and Liberation Philosophy. In a way, you could say we’ve “infiltrated” the institution, using its resources and laboratories to serve life.

CPM: The IVIC has been around for quite some time and, as you said, it’s founded on a more conventional model. How does your center fit in there?

XGB: IVIC was founded in 1959, and like other conventional research institutes, it has a hierarchical structure. To be recognized as a researcher, you need a postdoctorate, then come the PhDs, the doctoral students, the research support staff, and the technicians. Below them are the administrative staff, and at the very bottom, the janitorial staff.

IVIC’s structure resembles a pyramid, with many more “workers” than “researchers.” Researchers enjoy privileges, while everyone else is expected to serve them. At our center, we’re trying to break down this structure. We consider everyone who works there to be a researcher. How does that actually play out? We hold meetings to set goals and plan our projects collectively.

Our work focuses on connecting three key areas: academic knowledge production, knowledge generated by popular organizations, and public policy. This is crucial because the Ethics of Liberation seeks to co-construct knowledge, linking these three spheres whenever possible. That’s where the idea of co-responsibility, central to the Bolivarian Revolution and specifically the Popular Power Laws, comes into play. Knowledge is not built in isolation; it is linked to the commons, passed on from generation to generation, and created by interacting with different spheres that may appear separate but are interconnected.

Liberation happens when we share and build knowledge collectively to transform the world.

Campesinos improve seeds and pass down the knowledge from generation to generation. (Semillas del Pueblo)

CPM: The Seed Law is a good example of how these three spheres—academic knowledge, popular knowledge, and public policy—intersect. Can you explain the process behind the promotion of the law?

The movement to create a new seed law began when campesino organizations mobilized against a National Assembly bill that aimed to legalize GMOs and privatize seed production through breeder’s certificates. After a series of assemblies across the country, grassroots organizations crafted a new definition for campesino and Indigenous seeds that would be crucial in the development of the counterproposal.

Our center became involved in the movement, initially as participants in the “GMO-Free Venezuela” campaign and later as systematizers of the debates that were taking place. We used formal knowledge systems to give shape to the popular and ancestral knowledge that came up in the discussions and translated it into the legal form of a law, with all its technicalities.

This was the first level of interaction between different knowledge spheres. At another level, scientists from PROINPA, who specialize in non-GMO biotechnology, also contributed by rescuing ancestral seed knowledge. Finally, we worked with the National Assembly on drafting the final text.

The Seed Law is an example of how various spaces of knowledge production can come together, interact, and co-create. In the end, the law does away with extractivist practices regarding seeds, protects the knowledge of the producers, and proposes a new societal vision focused on preserving life.

CPM: To conclude, let’s discuss the Bolivarian Process and how it has impacted the social sciences and policymaking from the perspective of an Ethics of Liberation.

In the Bolivarian Process, participatory planning allows popular power, which is at the core of the revolution, to tangibly interact with the state. Participatory planning allows for the transformation of the modern state by dismantling its structures from the bottom up and from within, proposing new ways of living, planning, and executing policies together. This kind of planning allows us to propose another way of living and implementing policies together.

This idea is rooted in “mandar obedeciendo” [leading by obeying], a concept expressed in Venezuela’s communal councils and communes. This collective construction takes place in various stages, from developing projects to planning and co-managing with state actors while exercising popular control over the execution of the projects.

These projects are about community transformation, and they have different levels of participation. These range from communal council to the commune and even feeding into the legislative arena. We are also beginning to see some ministries develop public policies from this perspective.

All this reflects what Dussel calls the “principle of legitimacy” in Liberation Politics, which argues that decisions not only need to be approved by popular power, they must be co-constructed with it. This is the long journey we’ve embarked on with the Bolivarian Revolution. It’s a difficult path with many contradictions, but we are committed to the struggle.