We are going to be Earth’s best employer and Earth’s safest place to work.

— (Jeff Bezos, April 2021)

At the end of March 2021, a unionization drive in Bessemer, Alabama, by the Retail Workers (RWDSU)—one of the earliest attempts to organize an Amazon FC (Fulfillment Center)—failed to get the requisite numbers for certification. The campaign nevertheless highlighted workers’ frustrations over health and safety and created anxieties among Amazon executives over future unionization drives.

That apprehension was manifested a few weeks later. Amazon’s founder, Jeff Bezos, was stepping down as formal head of Amazon (though remaining as executive chairman) and felt compelled, in his ‘farewell’ letter to shareholders, to react to the growing criticisms of Amazon’s treatment of its workers. Then the world’s richest person, Bezos asserted that Amazon “cared deeply for our hourly employees, and we’re proud of the work environment we’ve created.”

He did, however, go on to admit that Amazon clearly needed “a better vision for our employees’ success.” This, he grandiloquently declared, would come from an ‘addition’ to Amazon’s fundamental values: “We are going to be Earth’s Best Employer and Earth’s Safest Place to Work.” This promise was very quickly enshrined as one of Amazon’s basic operating principles.

Fast forward three years to March 2024. Reality had exposed the shallowness of Amazon’s commitment, and Amazon’s VP for Global Workplace Health & Safety was assigned to publish a rebuttal. The VP praised Amazon’s ‘transparency’ in dealing with health and safety (H&S) and proudly shared concrete evidence of its new ‘caring’ trajectory. Amazon’s injury rate at its FCs, it asserted, had fallen by some 28% over the previous four years. This, the rebuttal declared, brought it in line with, or slightly above, the warehouse industry standard.

Transparency?

Before taking a closer dive into this claim, a few words about Amazon’s ‘transparency’ are called for. No company appreciates the power of information more than Amazon does, and no company, lofty proclamations aside, outdoes Amazon in using that capacity to reproduce its overall control. Any information Amazon provides does not come out of any civic duty; Amazon provides only what it is pushed to divulge by community pressure, the law of the land, and fear of unions ‘exploiting’ worker injuries on the job.

When Amazon tells us that “in the past several years, we’ve made a practice of transparently sharing our safety data because it helps us continue to learn and improve,” this merits more than a little skepticism. What Amazon seems unable to contemplate, never mind unwilling to act on, is that such information might not be something for Amazon to unilaterally and patronizingly ‘share’, but rather a matter of something that those directly experiencing the injuries—the workers—have a fundamental right to have.

In Ontario (Canada), where more than half of Amazon’s Canadian fulfillment centres are located, the law demands only that Amazon provide an injury rate for its combined operations. This undermines identifying facilities with sub-par safety performance as obvious sites for deeper investigation. When workers request these rates for their own facility, Amazon’s commitment to transparency quickly goes out the window. Amazon hides beyond the limited legal requirements and simply refuses to comply.1

In the U.S., the law does require that corporations provide injury data by facility. This allows for asking such questions as why FCs in the state of New York have much higher injury rates than Amazon’s average and why some Amazon facilities have injury rates two and three times that of others.

Yet, as positive as this is in comparison to Canada’s meek legal information requirements, Amazon is hardly a cheery complier. The U.S. Departments of Labour and of Justice have found it necessary to constantly levy citations and fines on Amazon for inadequate compliance with government information requests. Some twenty such cases were pending at last count [see for example here and here].

In both countries, pressures to resolve health and safety problems would be materially reinforced if Amazon respected its workers enough to take transparency beyond the minimum information legally required. This would include providing information across departments so workers could also pinpoint departments with special problems. This would also include passing on the information Amazon collects, but hordes for itself, on the impact of long shifts and consequent exhaustion on injuries. And it would openly and honestly investigate, rather than offer, glib assurances about whether new technologies actually ease workloads, or instead, intensify pressure on workers to work faster to pay off the cost of these investments.

Above all, if Amazon was genuinely concerned about the health and safety of workers, it would put the most verboten issue for the company on the table: the connection between production rates and injury rates. (We will return to this.)

Has Amazon Really Improved Its Injury Rates?

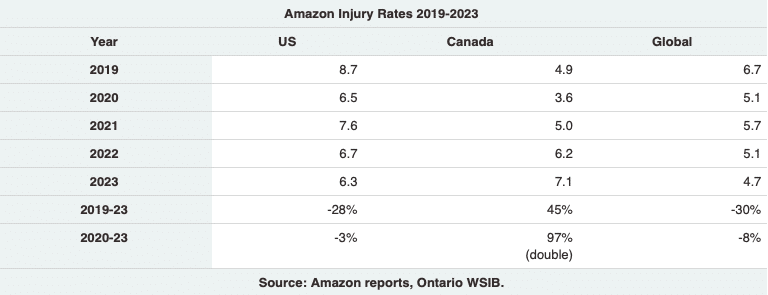

In 2016, U.S. Amazon workers had under 6 injuries per 100 full-time equivalent workers (FTE), which then rose to 8.7 in 2019.2 In 2020, for reasons that haven’t been clearly established, the injury rate dropped to 6.7, then bounced around and stood at 6.3 in 2023 (latest information).3

Amazon’s rebuttal conveniently set the base year at 2019—its worst year for injuries—making it easier to show 2023 in a better light. (In the process, the question of why Amazon allowed its injury rate to rise in the years to 2019 was, of course, not mentioned.) Had Amazon compared its injury rate to where it was in 2016 before the rate climbed to a peak, the 2016-2023 period would have shown a 7% deterioration in injury rates. And if it used 2020 instead of 2019 as the starting point (the latest data Bezos had when he made his dramatic promise on safety), the advance by 2023 would have been only 3%—a far cry from the 28% professed.

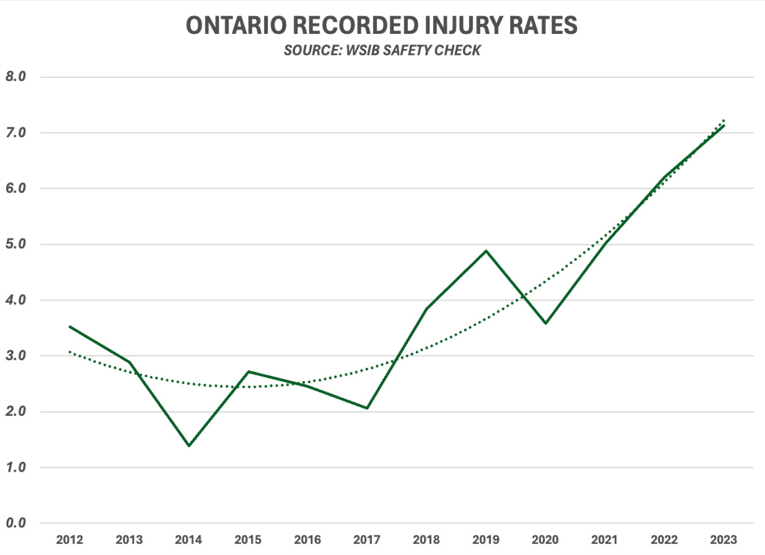

As for Ontario, Amazon’s rebuttal completely ignores Canadian injury trends. In Ontario, injury rates have, in fact, drastically worsened whatever year we start from. Sticking to Amazon’s reference to 2019-2023, Ontario’s injury rates rose by a criminally astonishing 45%! While Ontario injury rates were generally lower than in the U.S. in the past, by 2023, they had surpassed the U.S.4

If we move on and compare Amazon’s U.S. injury rates to Amazon’s overall global rates they are, based on Amazon’s own data, about a third higher in the U.S. Nor does that gap reflect a unique point; it has persisted over the years. (See data in Amazon’s rebuttal, referenced above.) And that stark difference is, in fact, larger than it seems: if we allow for the fact that the global data is inflated by the higher U.S. data, then the gap is significantly larger, perhaps closer to 50%.

This is not to suggest that Europe and non-US locations are a paradise for working conditions—Amazon workers in Europe have been every bit as critical of the state of health and safety at their FCs as their counterparts in the U.S. and Canada. It is, rather, raised to emphasize the especially poorer safety performance in the U.S.

Amazon’s Record Relative to the Rest of the Warehouse Sector

But let’s get back to the assertion in Amazon’s safety rebuttal: “We don’t aspire to be around the average—we want to be the best in the industries in which we operate.” There are three decisive problems with this measure of success.

First, the warehouse sector has injury rates about double that of the overall private sector (which is itself no paragon of healthy and safe workplaces). Compared to Bezos’ ambitious, if insincere, standard of having the safest workplaces “on Earth”, looking to match the industries “in which we operate” is therefore already a conspicuous retreat.5

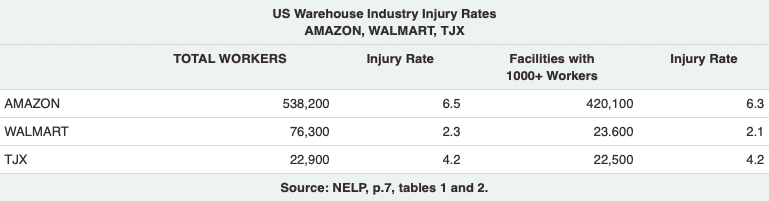

Second, this standard ignores the extent to which Amazon isn’t just another player in the warehouse sector, but rather its dominant actor. The National Employment Law Project (NELP) and Strategic Organizing Center (SOC), using the American data made available through the NLRB data, have rigorously broken down the commanding position of Amazon in the American warehouse sector: Amazon accounts for 37% of the sector’s workers while Walmart, which ranks second, only has 5%, and the rest is dispersed among some 7000 warehouses.

Going further, if we narrow this down to the facilities with more than 1000 workers—the largest facilities and those which effectively set the standards for the sector—Amazon accounts for a staggering 79% of the workforce. Walmart and TJX (which oversees TJMaxx, Marshall’s, Home Goods, Sierra, and Winners) account for 4% each.

Moreover, as the American researchers point out, the largest 48 warehouses in the U.S. are all operated by Amazon, each employing more than 3,000 people. Of the 119 warehouses in the U.S. that employ 2,000 people or more, Amazon operates all but five. And of the 250 warehouses with over 1000 workers, Amazon has 163 warehouses, while only Walmart and TJX have 10 or more warehouses of that scale.

When Amazon compares itself to the “warehouse sector,” it is, as NELP puts it, a slight of hand that essentially has Amazon “benchmarking against itself.” Amazon effectively IS the large warehouse sector.

Third, even if we compare injury rates among the three leading companies in the sector, Amazon’s injury rate—whether across all the companies in the sector or just the largest ones—is about triple that of Walmart and 50% above TJX. (In Ontario, the available data is very limited, but from what we can discern, the gap with, for example, UPS warehouses is in the range of Amazon’s gaps with the largest warehouses in the U.S.)

Worker Surveys of the Health and Safety Crisis

Worker surveys—getting information directly from workers—supplement the company-generated injury data. UNI Global Union, a federation of service and logistics unions across the globe, commissioned “the largest independent survey of Amazon workers ever conducted.” The survey focused particularly on Amazon’s invasive monitoring of work performance.

Most of the workers surveyed found the monitoring to be not only ‘excessive and opaque’ but also the corresponding production expectations that emerged ‘unrealistic’. The study documented that “striving to meet these unrealistic expectations has negative effects on [workers’] physical health and, even more acutely, their mental health.”

Similarly, a worker survey conducted by the Center for Urban Economic Development at the University of Illinois (Pain Points: Data on Work Intensity, Monitoring, and Health at Amazon Warehouses) found that:

- More than 2/3 of workers had to take time off the previous month to deal with pain and exhaustion; 1/3 have taken time off three or more times.

- More than half feel burned out from work.

- Two in five feel pressures to work faster most of the time, and the injuries and burnout are elevated among those feeling the pressure to work faster. Three in five workers say the monitoring is more intense than at their previous workplace, and 9% say it is less.

Like the other survey, this survey’s conclusions emphasized the link between production rates and health and safety:

a logistics system geared toward unrelenting speed and maximum customer convenience exacts a heavy toll on the health and well-being of many Amazon warehouse workers.

Production Rates and Health/Safety

None of the above is surprising. For example, the Seattle Times (Seattle is Amazon’s home base) quoted state regulators as pointing to a ‘direct connection’ between injuries and Amazon’s pressure to “maintain a very high pace of work.” The regulators further noted that the pace of work “makes it impractical for workers to follow Amazon’s safety training.” A February, 2023 OSHA news release similarly quotes the Assistant Secretary for Occupational Safety and Health urging Amazon to “take these injuries seriously and implement a company-wide strategy to protect their employees from these well-known and preventable hazards.”6

Common sense tells us that obsessively prioritizing speed is the enemy of workers’ health and safety. The point of all the monitoring by Amazon of stops and breaks and individual performance is overwhelmingly, if not singularly, used to pressure, threaten, and discipline workers to meet Amazon’s ever-intensifying standards. As one Amazon worker in the UNI survey caustically observed,

None of this information is ever used to actually improve conditions at work.

In fact, the most revealing aspect of the rebuttal of Amazon’s Global Safety Division is that their report never—never—mentions this potential conflict between aggressive production rates and their impact on workers. The reason for this brazen bias is obvious. The business of Amazon is maximizing profits while the ‘business’ of Amazon’s safety division is—at best—accepting the production rates as a given and, within that framework, doing what they marginally can about health and safety (perhaps more accurately, containing complaints from workers).

What’s To Be Done?

It’s not hard to set out steps that could ease the crisis in worker health and safety at Amazon. A partial list would include the following:

- Real transparency over injuries: It is the workers’ bodies that are affected, and they should have all the information that Amazon obsessively collects but doesn’t pass on to its workforce. And worker health and safety reps should have the run of the plant to conduct surveys that give voice to worker frustrations over Amazon policies.

- Ergonomic improvements: Ergonomic solutions exist, and Amazon engineers know about them. But they are not implemented because they don’t meet Amazon’s cost-benefit analysis. Workers must have crucial roles in such decisions and be part of an overall assessment of all Amazon operations.

- Time to recover from the impact of work: Workers need more breaks, more days off, job rotation if desired, and eventually, sharing in Amazon’s remarkable technological advances through shorter workdays for the same weekly pay.

- Humanized production speeds: Rather than facing ever-more intensive demands, production rates should be moderated and additional workers hired (which would not undermine customer demands for prompt delivery but highlight its cost).

The question, of course, is how to win such changes against a powerful corporation opposed to them. The law and workplace regulators have a vital role to play because much as we describe our society as ‘democratic’, the workplace imbalance between workers and corporations is anything but.

Fines on corporate abuses are, to be sure, welcome, but they cannot fix the disparity in workplace power. As of 2022, the total fines levied on Amazon for ignoring or blocking labour relations law totalled $81,000—an amount which, compared to Amazon’s after-tax profits in the previous year (over $33-billion) represents under 25 cents on every $100,000 of net profits (yes, one rusty quarter per hundred grand!).

Two crucial limits, even where ‘progressive’ administrators are in office, limit how far the law and its regulators will go in a capitalist society. One is that the law generally doesn’t set leading standards, but rather focusses on minimum standards. The other is that even when the pressure for change exists, the law cannot, from on-high, adequately enforce the multitude of injuries in the multitude of workplaces that occur on a daily basis—especially in the face of corporate resistance in the name of property rights. Only workers effectively organized in unions with a powerful workplace presence can potentially play that decentralized role.

A corollary of this argument is that as welcome as sympathetic workplace standards might be, the most important legal reform would be to shift workplace power relations and ease the barriers to unionization. The central orientation must be that corporations have no right whatsoever to influence who should represent workers; the question of representation must be an exclusive right of workers.

Fines and complicated legal procedures will not get us there. What is needed is union access to members (as opposed to the current monopoly of corporations’ mandatory meetings held to sully unionism) and automatic certification of the union involved if there is any violation of their rights, alongside criminal prosecution of those who formally or informally endorse intervention in these fundamental rights.

Amazon has—in a remarkably telling example of how they see the world—challenged the very notion of union certification, arguing that this violates the constitutional freedom to not associate, the alleged freedom to not be represented by a union. Amazon’s sublimely hypocritical idea of individual freedom is that of each worker individually negotiating with the collective power of Amazon stockholders as embodied in Amazon management and Amazon resources.

Conclusion:

Amazon glibly promised to make our workplaces the best and safest in the world. It then showed itself to be the barrier to fulfilling that promise. It’s up to us—the collective worker—to carry out the promise. This goal demands going beyond individual complaints or occasional protests. The health and safety crisis at Amazon cannot be truly addressed until workers organize—build the collective strategic power to challenge the priorities of management with our own priorities.

Short of building that collective capacity and institutionalizing it in a union, there is no counterbalance to Amazon’s greed and the competitive pressures on Amazon to stay on top at our expense. The issue is not just living with conditions as they are but recognizing that unless we effectively intervene, our workplace well-being will continue to get worse.

Health and safety struggles are paramount to building worker power because, unlike wage struggles (obviously very important) they are not reduced to collective bargaining every three-four (or five years) and left to our negotiators. Rather, H&S conflicts address the daily conditions of work—the pace of work, management’s unilateral power over their labour power, and the dignity of workers. And they do so through maximizing worker democracy: the on-going mass participation of workers in struggles over their needs and the confidence and skills consequently developed to participate in the higher levels of union decision-making.

Amazon is the second largest employer in the world, an iconic organizer of goods produced around the world and delivered to people’s doorsteps, a high-tech leader in streaming and the Cloud. It is surely not demanding too much to now insist that workers and their health will no longer be trampled and sacrificed to Amazon’s profit-driven march to capitalism’s pinnacles.

This report was prepared for Amazon Workers Solidarity (AWS). An earlier report was prepared by Stephen Maher and Scott Aquanno: “A Prime Competitor: Understanding Amazon’s Market Power.”

Amazon Worker Solidarity is a community group working to bolster the movement to organize Amazon workers. To join this independent grassroots effort or find out more, AWS can be contacted at [email protected].

Sam Gindin was research director of the Canadian Auto Workers from 1974—2000. He is co-author (with Leo Panitch) of The Making of Global Capitalism (Verso), and co-author with Leo Panitch and Steve Maher of The Socialist Challenge Today, the expanded and updated American edition (Haymarket).

Endnotes:

- ↩ In 2020, a Toronto Star reporter obtained information on injury rates in Canada by facility, but this leak was quickly closed down. Though the article referred to Canadian injury rates generally being much higher than he U.S., the comparisons were not quite comparable.

- ↩ Because Amazon’s workforce includes many full-timers, the full-time equivalent (FTE) is basically the total number of hours worked divided by 2000 (roughly the total working hrs in a year excluding overtime). 100 FTE’s is 2000*100 or 200,000 hrs. The injury rate per 100 FTE is therefore the total injuries divided by 200,000 hrs.

- ↩ One explanation points to Amazon controversially continuing to operate through COVID. This left it especially sensitive to publicity about its H&S record and it seemed to consequently take steps to limit production rates and contain injuries.

- ↩ For more on Ontario injuries and claims see The Maple, Feb 10, 2023.

- ↩ We ignore here Amazon’s duplicitous attempt to also include some comparisons to it as part of the ‘courier’ sector.

- ↩ See also the investigation of Amazon’s safety record in the report of the U.S. Senate Committee on Health Education, Labor and Pensions chaired by Bernie Sanders.