Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

Reading legacy Western media—which dominates the world information order—is painful. During the genocidal war against Palestinians, for instance, these media outlets (such as CNN, The New York Times, The Guardian, Le Monde, and Bild) have been unable to bring themselves to describe the Israeli military’s attacks on Palestinians. At most, and when it suits them, they resort to passive voice (‘Palestinians die’) or to a dangerous form of turning civilian areas into military targets (‘Hezbollah village’ or ‘Hamas command and control centre’).

A study of mainstream U.S. print media coverage during the first six weeks of the genocide in Gaza showed that ‘for every two Palestinian deaths, Palestinians are mentioned once. For every Israeli death, Israelis are mentioned eight times’. In other words, in mainstream media, an Israeli who dies will be mentioned 16 times more than a Palestinian who dies. This trend, which erases and dehumanises Palestinian casualties, seems to have accelerated as the number of Palestinians killed has increased exponentially, with an estimated 114,000 dead. There is no excuse for this abysmal coverage, which ignores the steady stream of information provided by the live reporting of a large number of Palestinian journalists and social media users in Gaza, at great risk to their lives, as well the deeper context for the U.S.-Israeli occupation, apartheid, and genocidal war provided by a wide range of analysis.

Television programmes are worse, with any critic of the genocide forced to make an admission (‘I condemn the 7 October attack by Hamas’ or ‘I condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine’) before the conversation can proceed, and, since many critics do not want to frame the discussion around this condemnation, the conversation never proceeds. This ritual act of condemnation is not merely an entry ticket into a conversation but an ideological concession that narrows the space for a genuine debate about the facts of when conflicts and crises begin, how to understand the structure of a conflict, and how best to ascertain the paths forward based on this longer-term historical and structural assessment. This type of discussion is called a conjunctural analysis, which provides political and social movements with the materials to intervene to shape the future and grounds the work of our institute. This newsletter will introduce you to four texts that are based on conjunctural analyses, but first I want to explain what such an analysis entails.

Alia Ahmad (Saudi Arabia), The Field, 2022.

The problem with information these days is not only its content, but equally its form. The velocity of information is striking, making it near impossible for a concerned person to discern both what is significant and what is true. Providing an excess of information that comes without proper, democratic analysis and is almost entirely controlled by a small oligarchy is its own form of censorship, exhausting the reader and viewer into submission. What is censored is not only information itself, although that does occur more than we admit, but also knowledge and wisdom. The news remains at the level of it happened, without explaining most of what happened at all: it does not explain why it happened, what caused it to happen, or its possible consequences. This form of reporting lies by omission, as events are neither static nor singular but part of a complex process.

Conjunctural analyses are an important tool for understanding that complexity, since they seek to explain the dynamic process of history at a certain point in time. Any given point in time is rooted in a past and a future: the past shapes the present, but the present also presages what may come in the future depending on how one intervenes now. That is why conjunctural analyses, derived from a history of Marxist analysis and from the work of the political and social movements that conduct them, are rooted in four principles:

- History. Since events do not take place in isolation but are part of a long-term process, there must be a distinction between incidental or occasional events and organic or structural events.

- Totality. Events are interconnected. They are part of a complex structure that encompasses various possibilities.

- Structure. Events take place within a lattice that includes economic, political, social, and cultural aspects and within which people are organised into classes and power blocs that interact through institutions and ideas.

- Politics. Events must be understood in an active way, which means asking how a political force will act to shape the future, rather than passively watching the future unfold. Answering this question requires a close analysis of the nature of class formation, the balance of political forces, and cultural traditions that could advance a certain political agenda.

Our Asia, Africa, and Latin America offices recently published four texts based on conjunctural analyses:

- Nepal’s Fight for Sovereignty, the Millennium Challenge Corporation, and the US’s New Cold War against China, jointly produced with Bampanth magazine and written by its chief editor Dr Mahesh Maskey, who was also Nepal’s ambassador to China. This text is only in English.

- A New World Born from the Ashes of the Old, written by Hanna Eid and produced with input from the West African People’s Organisation. This text is only in English.

- La criminalización de los cultivadores como coartada imperialista: economía política de las drogas en Colombia (The Criminalisation of Farmers as an Imperialist Alibi: The Political Economy of Drugs in Colombia), jointly researched and produced with Centro de Pensamiento y Diálogo Político and Coordinadora Nacional de Cultivadores de Coca, Amapola y Marihuana in Colombia and written by Karen Jessenia Gutiérrez Alfonso. This text is only in Spanish.

- A Revista Estudos do Sul Global (Journal of Global South Studies), which contains articles on themes such as imperialism, the character of finance in our times, and the tempo of the class struggle. This text is only in Portuguese.

I will write about each of these texts at greater length in the coming months, as their depth and quality help us navigate beneath the superficiality and sensationalism that typically define analyses of the present. For instance, Maskey’s intervention about the Nepali government’s acceptance of a U.S. government grant elucidates the dynamic structure of the U.S.-imposed New Cold War on Asia, while Hanna Eid’s assessment of the Alliance of Sahel States (Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger) enables us to understand the fight for sovereignty across West Africa as a whole. The report on the war on drugs provides a window into the pressures upon the government of President Gustavo Petro in Colombia, which requires an acknowledgment of the role of the lucrative international drug mafia in the country’s political establishment.

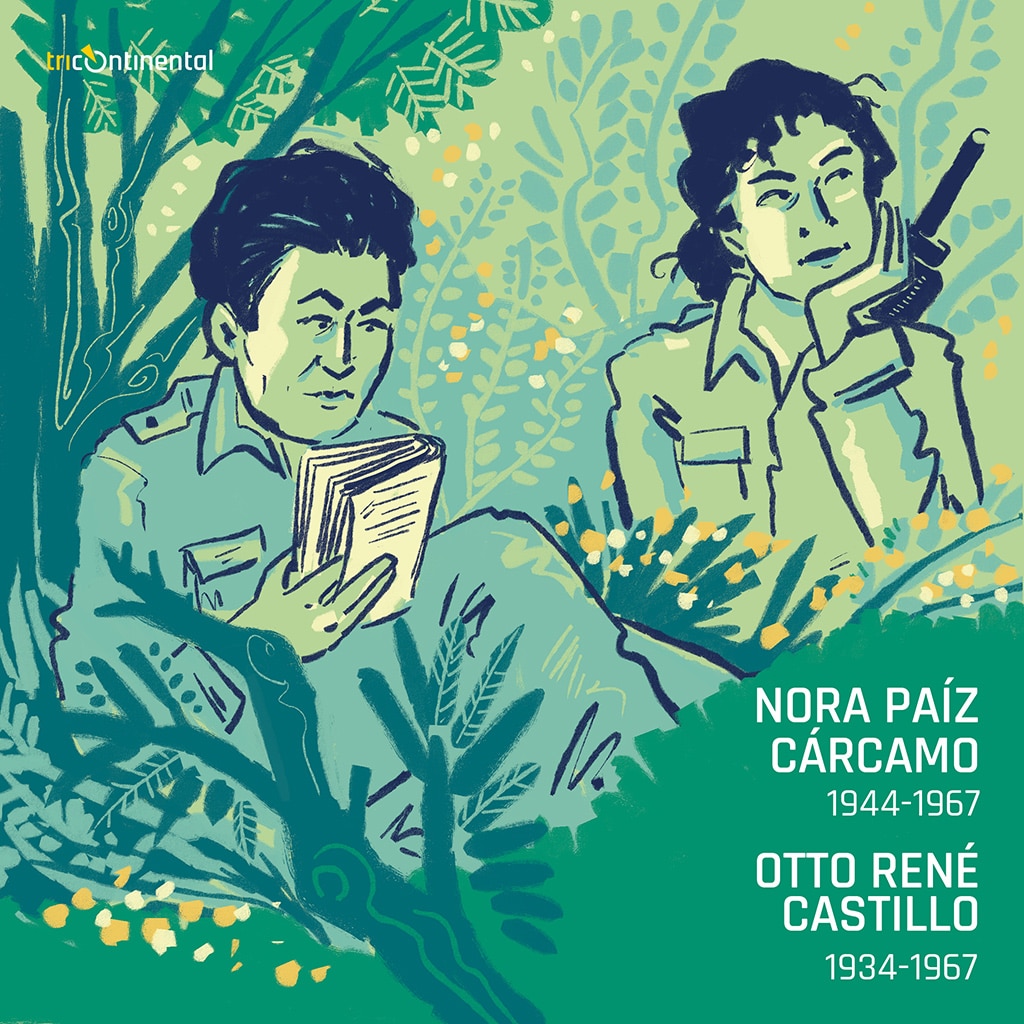

Years ago, I visited the Zacapa barracks, about two hours east of Guatemala City. The scene at the barracks was near-idyllic, its stone walls surrounded by green pastures, yet the sinister watch towers hinted of the bloodshed that took place here: this is where Nora Paiz Cárcamo (1944—1967), Otto René Castillo (1934—1967), other members of the Rebel Armed Forces (FAR), and about a dozen peasants were brutally tortured and burned alive. Both Nora and Otto were members of the communist movement that fought against the Guatemalan dictatorship; trained in the German Democratic Republic and Soviet Union, respectively; and joined the armed struggle in the Sierra de las Minas (named for the mines of jade, marble, and asbestos), where they were killed in March 1967. Later, Nora’s mother, Clemencia Cárcamo Sandoval, told the truth commission that her daughter’s bloody, fractured corpse was found with clubs fused into it, a sign of how brutally she had been beaten. Two years before he was murdered alongside his comrades, Otto, whose beautiful poems were inspired by the El Salvadoran guerrilla poet Roque Dalton (1935—1975), wrote an elegy to ‘apolitical intellectuals’:

I.

One day,

the apolitical

intellectuals

of my country

will be interrogated

by the humblest

of our people.They will be asked

what they did

when

their homeland was slowly

extinguished,

like a sweet fire,

small and alone.No one will ask them

about their suits,

or about their long

siestas

after lunch,

or about their sterile

battles with nothingness,

nor about

their ontological

way

of making money.

They won’t be questioned

about Greek mythology,

or about the self-disgust they felt

when someone, deep down,

accepted the fate of dying a coward’s death.

They’ll be asked nothing

about their absurd

justifications,

born in the shadow

of a total lie.II.

On that day

the humble people will come.

Those who had no place

in the books and poems

of the apolitical intellectuals,

yet, every day, brought them

their bread and milk,

their eggs and tortillas,

those who mended their clothes,

who drove their cars,

who cared for their dogs and tended their gardens,

who worked for them,

and they’ll ask:

‘What did you do when the poor

suffered, when the tenderness and life

was snuffed out of them?’.III.

Apolitical intellectuals

of my sweet country,

you will have nothing to say.A vulture of silence

will devour your insides.

Your own misery

will gnaw at your soul.

And you will be silent,

ashamed of yourselves.

Warmly,

Vijay