Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

The eighth continent is the Continent of Sleaze. You and I have never been there, only heard rumours about it. On that continent, there are rivers of money in which corporate executives bathe and from which they extract whatever they want in order to increase their power, privilege, and property. The corporate executives venture out to lay their hands on the wealth of the world and carry it back to their Continent of Sleaze. What remains is dust and shadows, barely enough for people to survive so that they can continue to labour and produce more social wealth for the Continent of Sleaze. Everyone sees this wealth being syphoned off to this other continent, but few want to acknowledge it. Most blame themselves for their poverty rather than the structure of corruption and pillaging that are inherent to the neocolonial capitalist system. Disconnected from social struggle, it is far easier to live innocently without that dangerous knowledge, that outrageous Promethean fire.

Corruption is like rust, corroding the metal of society. The greater the corruption, the deeper the collapse of social institutions and social fellowship. The incentive to follow rules withers as more and more people among the elite and their close associates benefit from their violation. Bribery and nepotism are the contours of modern corruption. The deadly sins of greed and pride are rewarded while the virtues of honesty and decency are mocked as being ‘naïve’. A hundred years ago, Mahatma Gandhi said that ‘the test of orderliness in a country is not the number of millionaires it owns, but the absence of starvation among its masses’. By that measure, the test of orderliness in the world today shows absolute chaos, governed by the ambition amongst the wealthy to become the world’s first trillionaire while global rates of hunger rise astronomically. The wealthy are permitted to remain wealthy and, indeed, to become wealthier by any means, and they have institutionalized corruption to further their ambitions.

In our dossier no. 82, How Neoliberalism Has Wielded ‘Corruption’ to Privatise Life in Africa, we examine the problem of corruption, which has threatened not only the integrity of public institutions, but also of society in general. The main thesis is that since the onset of the neoliberal era in the 1980s—1990s, the concept of corruption has been narrowed to describe only public sector corruption. One of the main agents for this reduced idea of corruption is Transparency International (TI), founded in 1993 in Germany, which greatly influenced the United Nations Convention against Corruption (2003). Since then, governments in the Global North have used TI data to pressure multilateral agencies (such as the International Monetary Fund, IMF) to make this idea of ‘corruption’ central to their operations in the developing world. If a country was shown to have a high corruption score, then it became more expensive for that country to access funds through credit markets, giving these agencies more leverage over its policies and overall governance. These agencies told the developing country that, in order to improve its corruption score, it needed to reform its public institutions, such as by shrinking the size of public bureaucracy—even, strangely, the regulatory bodies of the state—and the number of state employees overall. In the 1990s, the IMF began to require developing nations to cut their wage bill for public sector employees as a key condition for granting loans and financial assistance. Because they so desperately need funds to cover their external debts, many countries have acquiesced to this condition and slashed their public sector. Today, 21% of the European workforce, on average, is employed in the public sector; in contrast, that number is a mere 2.38% in Mali, 3.6% in Nigeria, and 6.7% in Zambia, which in turn limits these states’ capacity to manage and regulate large multinational corporations on the African continent. This stark contrast is the reason why this dossier focuses on the African continent.

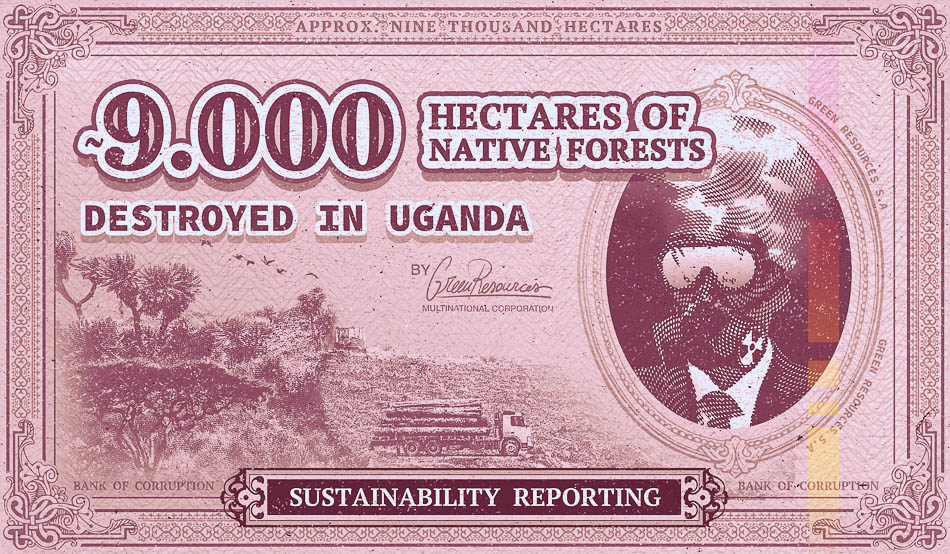

Today, African scholarship rarely defines the terms of African actuality. The concepts of neocolonialism—such as ‘structural adjustment’, ‘market liberalisation’, ‘corruption’, and ‘good governance’—are forcibly imposed on the continent and its intellectuals, ahistorically eliding any serious mention of the legacy of colonialism, the struggles to establish state sovereignty and reclaim the dignity of the people, and the theories of development that emerge in out of these histories and struggles. There is an a priori racist belief that African states are corrupt and that the absence of state institutions will somehow allow for growth and development. Yet, when regulatory institutions are eroded, it is foreign multinational corporations that benefit the most.

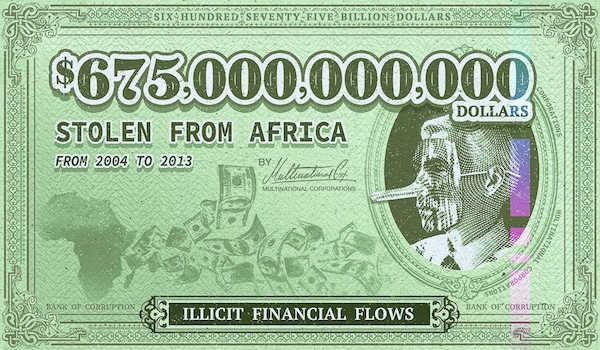

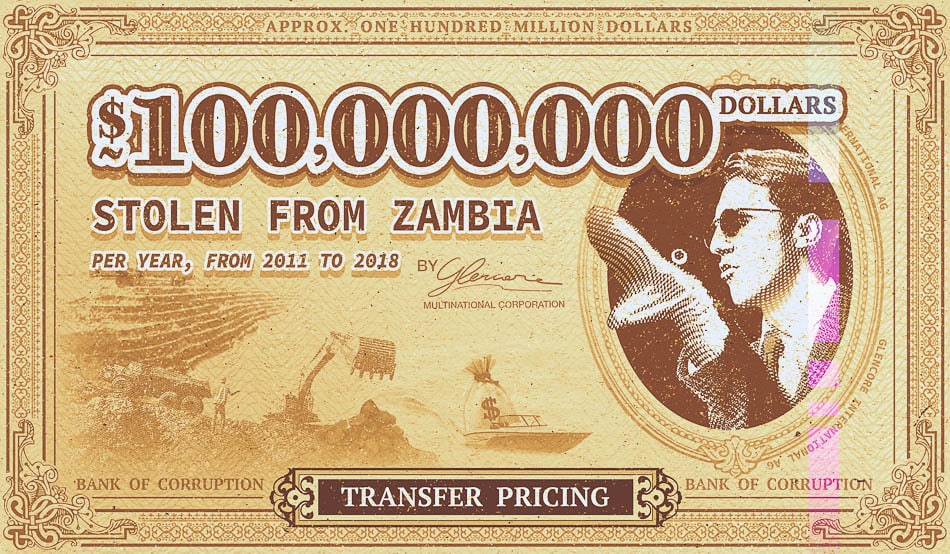

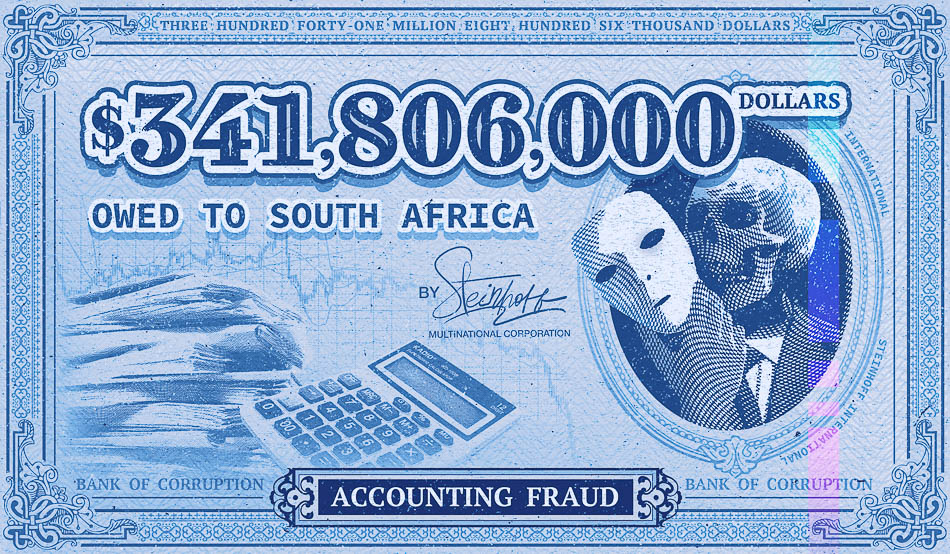

Africa is a continent rich in resources, home to around 30% of the world’s mineral reserves (including 40% of the world’s gold, up to 90% of its chromium and platinum, and the largest reserves of cobalt, diamonds, platinum, and uranium), 8% of the world’s natural gas, and 12% of the world’s oil reserves; it also holds 65% of the world’s arable land and 10% of the planet’s internal renewable fresh water sources. However—largely due to the policies of the colonial period and their continuation in the neocolonial period—African states have been unable to harness those resources for their own development. The ruling elites in these nation-states have turned over their sovereignty to enormously powerful multinational corporations (MNCs) whose profits are far beyond these states’ Gross Domestic Products. MNCs declare only a fraction of their earnings, about two-thirds of which are ‘mispriced’ and much of which is sent off to tax havens. A 2021 report, for instance, showed that capital flight from thirty African countries between 1970 and 2018 totalled $2 trillion (in 2018 U.S. dollars) while the African Development Bank noted that illicit financial outflows from Africa increased somewhere from U.S. $1.22 to $1.35 trillion between 1980 and 2009. Today, it is estimated that illegal financial flows out of Africa amount to $88.6 billion per year.

The ruling elites in these African states accede to these firms, often because they are bribed to turn a blind eye to corporate corruption. In 2016, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa reported that 99.5% of bribes to African officials are paid by non-African firms and suggested that large mining conglomerates are knee deep in the bribery industry. Corporate bribery certainly pays off: the rate of return earned by Western-based resource extraction firms is considerable, saving the MNCs hundreds of billions in unpaid taxes. In other words, Africa’s ruling elites are selling off their countries cheaply. Meanwhile, there is nothing left for the children who live above the copper and the gold. They cannot read the agreements that their governments make with the mining companies. Nor can many of their parents.

On the Continent of Sleaze, there is no care about the tidal corruption that sweeps across the world. There is no concern for the casual theft of hundreds of billions of dollars through mechanisms that have been anointed by accountancy firms and normalised by multilateral agencies that sniff at the slightest infraction in the public sector in the Global South. There is no thought given to colonialism and neocolonialism, words that have no meaning on the Continent of Sleaze.

In his remarkable book Sounds of a Cowhide Drum (1971), the South African poet Oswald Mbuyiseni Mtshali published ‘Always a Suspect’. This poem tackles one of the most ubiquitous aspects of racism—the assumption that a Black man is a thief. It is never the colonial plunderer who is accused of theft but the colonised, who are themselves victims of the theft of their lands and wealth. Mtshali’s poem illustrates how the racist assumption of African corruption seeps even to everyday life:

I get up in the morning

and dress up like a gentleman —

A white shirt, a tie, and a suit.I walk into the street

to be met by a man

who tells me ‘to produce’.I show him

the document of my existence

to be scrutinised and given the nod.Then I enter the foyer of the building

to have my way barred by a commissionaire

‘What do you want?’.I trudge the city pavements

side by side with ‘madam’

who shifts her handbag

from my side to the other,

and looks at me with eyes that say

‘Ha! Ha! I know who you are;

beneath those fine clothes

ticks the heart of a thief’.

Warmly,

Vijay