- Part 1: Populists fought the ruling class

- Part 2: Populism or fascism?

- Part 3: The history of Black Populism

- Part 4: Two paths after slavery’s end

- Part 5: A Cuban perspective on race and revolution

The Wilmington, North Carolina, massacre of 1898, also called a coup, was not a spontaneous eruption of white supremacist violence, but instead came from the top leadership of the Democratic Party and was backed by the rich. The purpose was to drive Black people out of public life and ensure minority rule by wealthy white businessmen. How did they pull this off? Manipulation of the mass media was a principal factor, along with setting up pseudo-grassroots organizations throughout the state.

The road to 1898 began some 28 years earlier when the Democrats retook control of the state legislature in 1870. Over this long period, they whittled away at the gains of Reconstruction in North Carolina. Despite that, both the Republicans and the People’s Party continued to challenge the openly racist Democratic Party throughout the period.

As Thomas Frank put it,

This was the state where Populism—in ‘fusion’ with the local Republican Party–actually captured the government in 1894 and ‘96 and then made reforms that allowed Black [people] to sometimes gain political power in places where they were in the majority. (“The People, No: A Brief History of Anti-Populism”)

The fusion movement won all the statewide races in 1894 and 1896, in fact. This was a significant challenge to the moneyed elites. And despite the national turn (the reactionary Supreme Court enacted the apartheid “separate but equal” doctrine in 1896 in the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling) the city of Wilmington was one place where Black people continued to hold public office, and it was also governed by a Populist-Republican fusion coalition.

The White Supremacy Campaign

In 1898, North Carolina’s seats in both the U.S. House and Senate were up for grabs, with urban Wilmington being important in these elections, giving the events a national significance. The new Democratic state party chair was Furnifold McLendel Simmons. He was born on his father’s plantation in 1854 and lived until 1940, even chairing the U.S. Senate Finance Committee during WWI. In 1897, Simmons was tasked with developing a strategy for the Democrats to secure power in North Carolina, and that strategy was bluntly named the White Supremacy Campaign.

The idea was this: If they could make anti-Blackness the number one political issue, crowding everything else out, then they could defeat any Republican and People’s Party challengers. On top of that, real-world violence (as well as the threat of violence) could effectively prevent masses of Black voters from going to the polls.

In practice, the strategy worked just as planned. But as Timothy B. Tyson put it,

A propaganda campaign slandering African-Americans would not come cheap. Simmons made secret deals with railroads, banks and industrialists. In exchange for donations right away, the Democrats pledged to slash corporate taxes after their victory. (The Ghosts of 1898: Wilmington’s Race Riot and the Rise of White Supremacy).

Sound familiar? The White Supremacy Campaign was backed by the rich and carried out on their behalf, just like today’s movements targeting immigrants, LGBTQ+, and other oppressed people.

Racist media manipulation and phony grassroots organizations

Tyson continues:

At the center of their strategy lay the gifts and assets of [Josephus] Daniels, editor and publisher of The News and Observer [newspaper]. He spearheaded a propaganda effort that made white partisans angry enough to commit electoral fraud and mass murder. It would not be merely a campaign of heated rhetoric but also one of violence and intimidation. Daniels called Simmons ‘a genius in putting everybody to work–men who could write, men who could speak, and men who could ride–the last by no means the least important.’ By ‘ride,’ Daniels employed a euphemism for vigilante terror. Black North Carolinians had to be kept away from the polls by any means necessary.

In the statewide press, Daniels harped on the horror of Wilmington, the center of “Negro domination” in the state. (Never mind that the state legislature was 2/3rds white.) This is very similar to the politics in contemporary Louisiana, where Governor Jeff Landry whips up fear about violent crime centered in majority-Black metro New Orleans and Baton Rouge.

Simmons tapped the talented young cartoonist Norman Jennett to crystalize the campaign’s message into memorable images. His caricatures were like the racist memes of that era, and the antithesis of the iconic class-conscious labor cartoons of the period. They were designed to produce an immediate, visceral reaction.

The campaign’s leaders went so far as to establish white supremacist clubs across the state, creating the impression of a popular groundswell. This top-down method for generating reactionary outrage has had a long life mirrored in today’s well-funded, fake grassroots organizations like Moms for Liberty and “school choice” outfits. These types of groups successfully get media coverage, presenting themselves as concerned parents who happened to come together over a common cause when really they are funded by the billionaire Koch brothers or the Wal-Mart heirs.

Perhaps even more outrageous, the North Carolina racists set up a phony White Labor Union backed by the Wilmington Chamber of Commerce and the Merchant’s Association. Through this organization, they could divert some white workers from their real grievances against the bosses and focus their anxiety onto competition with Black workers, uniting them in a campaign to keep Black workers out of the more desirable jobs–and elected offices.

As we have seen previously, this kind of deceptive appeal to the working class became a hallmark of fascism in the 20th Century. It aimed to draw workers away from the real organizations that fought for their interests.

In Wilmington, the statewide White Supremacy Campaign linked up with the “Secret Nine,” a grouping of nine wealthy white men who were plotting a coup against the Wilmington government. Their plans culminated in the Wilmington massacre. State Party Chair Simmons worked with the Nine. Therefore, the Wilmington events can only be understood in relation to this bigger campaign of state and national politics. And those events certainly did not well up from the white working class in Wilmington or elsewhere.

Poor white Southerners lacked leadership

In assessing the pre-populist Reconstruction period, W.E.B. du Bois pointed out a key flaw in all attempts to transform the society of the South: The Southern white working class lacked leadership of their own, and therefore tended to be led by the rich white planters whose class interests were diametrically opposed to their own. This was analogous to those workers today who think that apartheid South African emerald-mine heir Elon Musk has the same interests as them. Du Bois said:

The mass of poor whites were in an anomalous position. Those of them who were intelligent or had during slavery accumulated any capital or achieved any position, had always attached themselves in sympathy and interest to the planter class. This meant that the mass of ignorant poor white labor had practically no intelligent leadership. Only here and there were there men, like Hinton Helper [still a white supremacist], who were actual leaders of the poor whites against the planters. The poor white was in a quandary with regard to emancipation. He had viewed slavery as the cause of his own degradation, but he now viewed the free Negro as a threat to his very existence. Suppose that freedom for the Negro meant that Negroes might rise to be landholders, planters and employers? The poor whites thus might lose the last shred of respectability. They had been used to seeing certain classes of the Black slaves above them in economic prosperity and social power. But after all, they were still Negroes and slaves. Now that freedom had come, poor whites were faced by the dilemma of recognizing the Negroes as equals or of bending every effort to still keep them beneath the white mass in income and social power. (Black Reconstruction in America)

If Southern white workers had historically lacked their own leadership, then the advent of populism in the post-Reconstruction period was one solution to that problem. It was not the solution, only a start. As we have already pointed out, there were many contradictions. For example, the movement included wealthier farmers who tended to dominate organizations. Anti-segregationist tendencies struggled with segregationist tendencies. But it still was a start. Organizing was happening across the color line–imperfectly, in fits and starts. But it was happening.

Poor farmers in the South and West were teaming up with industrial labor unions and identifying common enemies in the capitalist class. When the ruling class got the ideological and organizational upper hand with the White Supremacy Campaign and similar onslaughts, this progress was reversed. The Southern white working class went back to following the rich planters and the multinational working-class movement was severely weakened. Then as now, white supremacy is capitalist-class supremacy.

A ‘vile and villainous’ editorial

It should now be clear that the scene was primed for violence because of the White Supremacy Campaign. No one local incident could be the necessary cause. The powder keg had to already be there in order for something to set it off. One such incident is the response of a Black newspaper editorial to a violent speech calling for the mass murder of Black men.

The one who gave that speech was savvy political figure Rebecca Latimer Felton. She was born to rich Georgia slave owners and upon reaching adulthood, owned slaves herself, along with husband William Harrell Felton. She was the main strategist and propagandist behind her husband’s political career, leading him to three stints in the U.S. House as an independent Democrat. Rebecca Felton herself became the first woman in the U.S. Senate in 1922, serving for one day.

The contradictory nature of the Feltons’ politics made them especially dangerous. Rebecca was a prominent proponent of women’s suffrage—white women’s suffrage. They supported education reform and some other progressive causes of the day. They sometimes moved in the same circles as the Populists. But they were dyed-in-the-wool racists. The Civil War had not cured these former slave-owners of their old views.

On Aug. 11, 1897, Rebecca Felton addressed the Georgia Agricultural Society, making her pitch for mass lynching. She brought up the old trope about Black men raping white women and said,

If it needs lynching to protect woman’s dearest possession from the ravening human beasts—then I say lynch, a thousand times a week if necessary.

Black Wilmington newspaper editor Alexander Lightfoot Manly responded with an editorial in his paper, The Daily Record, which may have been the only Black-owned newspaper in the country at the time. (Manly was the son of a freedman and a free woman of color. He was a descendant of North Carolina Governor Charles Manly and a woman the governor enslaved, Corinne Manly. Alexander Manly graduated from the historically Black Hampton University in Virginia before settling in Wilmington.)

Manly published his response to Felton’s disgusting speech barely a week later on Aug. 18, 1898 barely a week after it had been reprinted. He called out the hypocrisy of the white demagogues who harp on alleged Black rapists while white men are allowed—in fact encouraged by all the social institutions—to sexually abuse Black women. And he affirmed in no uncertain terms that most sexual and romantic relations between Black men and white women were consensual; that was intolerable to the racists. In part, Manly’s letter read:

Mrs. Felton begins well, for she admits that education will better protect the girls on the farm from the assaulter. This we admit and it should not be confined to the white any more than to the colored girls. The papers are filled often with reports of rapes of white women and the subsequent lynchings of the alleged rapists. The editors pour forth volumes of aspersions against all Negroes because of the few who may be guilty. If the papers and speakers of the other race would condemn the commission of the crime because it is crime and not try to make it appear that the Negroes were the only criminals, they would find their strongest allies in the intelligent Negroes themselves; and together the whites and Blacks would root the evil out of both races. … Don’t ever think that your women will remain pure while you are debauching ours. You sow the seeds—the harvest will come in due time.

Despite the dated patriarchal language about women’s purity, the truth of Manly’s words comes through. It was a fact that women of African descent were sexually abused from slavery on down—systematically.

Manly was quite restrained considering the speech he was responding to. The response of the racist press was rather less so. A headline in the Aug. 24 issue of the Wilmington Star read: “Vile and Villainous…Outrageous Attack on White Women by a Negro Paper Published in Wilmington.” Below this headline was a paragraph implying imminent danger for the white population followed by a long excerpt from Manly’s editorial. Similar coverage appeared all over the state.

A pogrom and a coup d’etat

This hysterical press reaction was just the beginning. In the leadup to the Nov. 8 statewide elections, the Secret Nine and their movement terrorized Wilmington’s Black population. These were pogroms, that is, violent riots meant to harm, intimidate, and expel oppressed minority groups. The word entered English through Russian and Yiddish and referred mainly to anti-Jewish riots in the old Russian Empire stoked by the Czarist regime. Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass) was one of the most infamous pogroms. It was carried out in Germany by the Nazis in 1938. The name referred to the shards of glass littering the streets after fascist mobs smashed the windows of Jewish synagogues, shops, and other buildings. The Klan’s decades of terrorism following the U.S. Civil War provide many more examples. Wilmington and the Red Shirts—modeled on the Klan and backed by the Democratic Party—was a big one. It was also a coup d’etat.

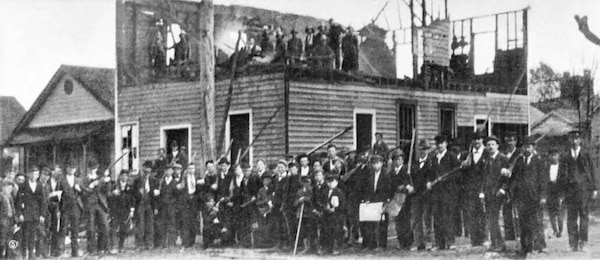

White Supremacy Campaign leaders provided the white mobs with food and liquor. They spent $1,200 on an early mounted machine gun, the Gatling gun, to use against unarmed Black people. On Nov. 10, a crowd of 2,000 burned down the Black-owned Daily Record at the instruction of former Confederate Colonel Alfred Waddell, who was leading hate rallies. They beat and intimidated every Black person they could find, especially those who had the audacity to exercise their legal right to vote. Estimates of the dead range from 60 to over 300 people. What is clear is that communities were torn apart as thousands of Black people fled the city along with white people whom the racists identified as allies of the Black Wilmingtonians.

The coup perpetrators kicked out the Black office-holders and threw out the aldermen, replacing them with their own people who then appointed Alfred Waddell as mayor. He illegally remained in that position until 1906. The Democratic Party’s white supremacist candidates won the congressional elections and in the following years, Black North Carolinians were effectively disenfranchised.

Scramble to be the biggest racist

Populist politicians had worked together with Republicans in the Wilmington fusion government. By the nature of the enterprise, this coalition challenged racism. As described previously in this series, the populist movement involved repeated attempts to combine the strength of both the Black and white laboring masses on the basis of their shared class interests. But was the populist movement totally insulated from racism? Did the populists in North Carolina maintain a principled stand against the White Supremacy Campaign? Unfortunately, the answer to both these questions is “no.”

Take the editorial published first in the Progressive Farmer and reprinted in the Charlotte People’s Paper on Nov. 4, just before the election. The article correctly characterizes the Democratic Party’s White Supremacy Campaign as swindling whose real objective was to secure “a legislature which will be the tool of plutocracy—of the moneyed men, and that will give us an election law, whose meaning shall be ‘those who own property must rule.’”

Very well, but the author went on to say that among the Democrats there is “not one who is a more earnest advocate of white supremacy than we.” There we have it! Sections of the populist movement attacked the Democrats from the right, attempting to prove that they were the true white supremacists.

This should be familiar to us today. This sort of capitulation happens when sections of the progressive movement adopt transphobic and other reactionary positions. It happens when sections of the progressive movement attack Palestine solidarity, following the lead of the Democratic Party. Something similar happens when politicians elected to Congress on a progressive ticket vote in favor of the war budget. Something similar happens when supposedly progressive politicians try to out-Trump Trump by demonizing immigrants and trans people. That does not mean that today’s movements that enable the election of progressive-talking candidates are disingenuous, and even less so is the case of populism, which involved a big wave of organizing against the big corporations and banks in the 1890s.

As we have seen, this movement had its basis in the massive agricultural alliances that sprang up in the 1870s, including Black farmers’ alliances. The movement repeatedly attempted to organize white and Black farmers on the basis of their shared class interests. Movement leaders were keenly aware of these shared interests. That was their objective situation, and they knew that in order to take on the rich, multi-racial collaboration was necessary. This fact could not prevent all racism in the movement, and movement segregation was never overcome. And when the movement waned the racist elements could come to the fore. (Wilmington in 1898 was one of the last stands of populism, with the People’s Party dwindling to a tiny size). This shift to the right was driven in part by the pressures of things like the White Supremacy Campaign.

One of the most extreme cases is that of Tom Watson, who in 1896 had been the vice presidential candidate with Democrat William Jennings Bryan on the Populist Party ticket. During his time as a leader in the populist movement, he championed poor farmers and called for Black and white unity. He ran for president on the People’s Party ticket in 1904 and 1908, but by that time, the populist movement was basically over. In the period that followed, Watson launched a new career publishing a rabidly racist magazine. Like the fascistic social-media influencers of today, his income depended upon inciting readers with anti-Black, antisemitic, and anti-Catholic/southern European immigrant garbage. He also denounced socialism, which other former populists were embracing.

My argument is not that true populists could not be racist. On the contrary, the inherent contradictions of the movement—its class and national composition, the post-Reconstruction dynamics–are the very source of its pitfalls. There was no pure populism that was then corrupted by influences from outside. Nevertheless, there are essential tendencies of the movement to consider. Again, the tendency toward the alliance of Black and white labor on the basis of their shared class interests. The turn of white populists in North Carolina to accept the logic of the Democrat’s White Supremacy Campaign–to attack the Democrats from the right, attempting to be more racist than them: That is an example of the emancipatory potential of populism being squandered.

Du Bois is again helpful in thinking through this troubling problem. There is an analogy with the Northern Union’s position on slavery during the war. Even though the Northern Union’s initial aim was not to end slavery, it became apparent—because of the objective situation in front of them—that it was impossible to preserve the United States without ending slavery. They had to become anti-slavery, regardless of their personal prejudices.

Until late in the war, Lincoln himself did not always envision an integrated society. He considered many proposals regarding the day after emancipation, one of which was the mass deportation of Black people to Africa. When presented with mathematical proof that this was unfeasible, Lincoln abandoned the idea. (Black Reconstruction in America)

The Northern Union forces had to align themselves with the Black masses who were emancipating themselves during the war, and through shared struggle, many became more progressive. Similarly, when the populist wave appeared, the struggle required unity across race, even if that was never fully achieved. When Reconstruction was defeated, reaction held sway. When populism was defeated, likewise.