I have this sense of impending doom…

— Fire historian Stephen Pyne (1993)

In 1981, in one of his last articles, Los Angeles’s best-known environmental writer, Richard Lillard, challenged Frederick Jackson Turner’s famous thesis that the American frontier-and with it, the frontiersman-disappeared in 1890. As a matter of fact, Lillard asserted, the frontier was alive and well in the Edenic canyons above Malibu and Hollywood. The unique challenge of the wild mountains so near the big city brought out the true grit in the self-selected population of hill dwellers. “The whole hillside and canyon ambiance, almost always fresh and wildsmelling, both attracts and holds the kind of individual that Frederick Turner and many a traveller, Tocqueville included, knew in the backwoods districts. “The neighborly and self-reliant hill folk, moreover, were tempered to heroic mettle by the implacable constancy of the fire danger,

keeping an outlook for arsonists or children playing with matches, as their forefathers once kept alert for hostile aborigines.

At the same time, however, Lillard warned harshly against the creeping threat of mountain society’s nemesis: sloping suburbia.

It is not habitation amid wilderness. Mankind has conquered nature instead of adjusting to it. Often the new instant enclaves have a supermarket, a cleaning and dyeing establishment, and a laundromat. The immigrating mini-city populace consists of country club types rather than hillsiders.

Although Lillard was writing only a decade and a half ago, his mountain frontier is now extinct. “Country club types” have everywhere conquered and now monopolize the picturesque seacoasts and foothills. Despite brave but belated attempts at open space conservation, like those of the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, Southern California’s remnant natural landscape continues to be destroyed or privatized. As we saw earlier, fire itself accelerates gentrification and the replacement of bohemian lifestyles by snobbery and exclusiveness. The real impetus of this movement to the hills is no longer love of the great outdoors or frontier rusticity, but, as critic Reyner Banham recognized in the 1960s, the search for absolute “thickets of privacy” outside the dense fabric of common citizenship and urban life.

Hillside homebuilding, moreover, has despoiled the natural heritage of the majority for the sake of an affluent few. Instead of protecting “significant ecological areas” as required by law, county planning commissions have historically been the malleable tools of hillside developers. Much of the beautiful coastal sage and canyon riparian ecosystems of the Santa Monica Mountains have been supplanted by castles and “guard-gate prestige.” Elsewhere in Southern California-in the Verdugo, Puente, San Jose, San Joaquin, and San Raphael Hills, as well as the Santa Susana, Santa Ana, and San Gabriel Mountains-tens of thousands of acres of oak and walnut woodland have been destroyed by bulldozers to make room for similar posh developments.

And the “flatland” majority-including the poor taxpayers of the Westlake district, most of whom have never seen a Malibu sunsetwill continue to subsidize the ever increasing expense of maintaining and, when necessary, rebuilding sloping suburbia. As Richard Minnich points out, hillside homeowners, unlike tenement dwellers, have access to almost unlimited fire protection.

The money flows to the Santa Monica Mountains instead of poor areas of Los Angeles because fighting firestorms is an emergency action. In fact, all wildland fires, even one acre spots, are treated as emergencies. The Forest Service and other land management agencies have no a priori budget. After the fire is suppressed, they just send a bill to the government. Budgeting is a posteriori, which means there are no strings. They can spend as recklessly as possible. Urban fires aren’t treated this way.

Meanwhile, the suburbanization of Southern California’s remaining wild landscapes has only accelerated in the face of a perceived deterioration of the metropolitan core. As middle- and upper-class families flee Los Angeles (especially its older, “urbanized suburbs” like the San Fernando Valley), they seek sanctuaries ever deeper in the rugged contours of the chaparral firebelt. The population, for example, of the Thousand Oaks-Agoura Hills corridor-the crucible of almost all Malibu firestorms-has tripled since 1970 (to nearly 60,000), with hundreds of new homes scattered like so much kindling across isolated hilltops and ridges.

Ignoring every lesson of the recent fires and earthquakes, two new megadevelopments, Newhall Ranch and Ritter Ranch, totaling 42,000 homes, are under construction in the environmentally sensitive, fireprone Santa Clarita and Leona Valley areas of northern Los Angeles County. Statewide, some seven million inhabitants-the whitest and wealthiest segment of the population-now live in the suburban-chaparral border zone where wildfire is king. Excluding national parks and military bases, California suffered an incredible 10,000 wildfires per year during the 1980s.

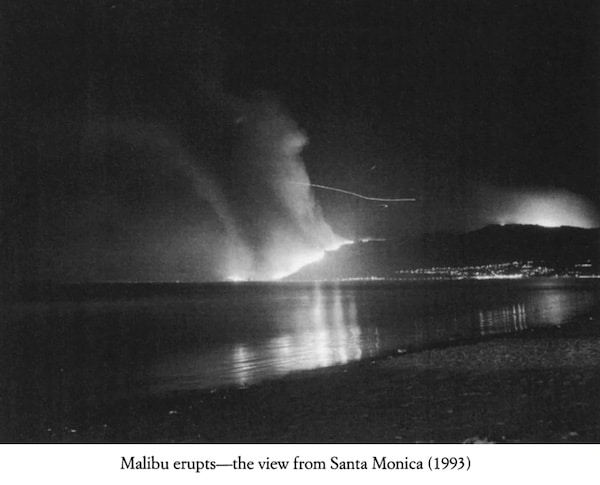

At the same time, suburban firestorms are becoming ever more apocalyptic. The social cost of fire has increased in almost geometric relation to the linear growth of firebelt suburb populations. Twothirds of all the homes and dwellings destroyed by wildfire since statewide record keeping began in 1923 have been burnt since 1980. If, as Stephen Pyne has suggested, the 1956 Malibu fire inaugurated a new fire regime, then the 1991 Oakland fire ($1.7 billion insured damage) and the 1993 Southern California fire complex ($1 billion) marked the emergence of a new, “postsuburban” fire regime.

The increased dangers of this “fire boom” are most obvious to those who risk their lives every year fighting mountain firestorms. As Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt complained while visiting the Malibu fire scene in 1993: “Fire-fighting is getting more expensive, more hazardous.” To use a military analogy, the new density of hillside housing has transformed the battle against wildfire from a wide-ranging war of maneuver into the equivalent of street fighting. Firefighters’ energies are now dispersed into house-by-house defenses, while traditional wildfire techniques, like the use of backfires, are vitiated by the threat to nearby homes. As a result, there is a dramatically increased risk of firefighters’ being trapped by erratic and rapidly moving fire fronts.

This is exactly what happened to four engines from the Glendale and Los Angeles city fire departments on the second day of the 1996 Malibu fire. Although the fire did little property damage, it came close to wiping out an entire fire line of defenders. The firefighters had been dispatched to save some ridge-top homes perched above Malibu Bowl in Corral Canyon, when shifting winds suddenly fanned flames up a steep south-facing hillside. The captain in charge of the Glendale fire crew, who would normally have watched for such flare-ups, was preoccupied with laying line to protect the homes. As the fire unexpectedly erupted across the eucalyptusplanted ridge, “Engine 24’s captain felt a blast of heat followed by a rain of embers. He ordered his personnel to abandon their hose line and run.” One firefighter, 53-year-old William Jensen, held his position with almost suicidal courage in order to cover his fleeing comrades with spray from his hose. He was hideously burned over 70 percent of his body and, although he lived, required 16 separate skin-graft operations before he left the hospital four months later.

Meanwhile, nearby units from Los Angeles were desperately trying to escape from the closing circle of flames. The heavy smoke, however, stalled Engine 10, and “the four men on board were only able to open one of the aluminized blankets each carried as protection. Three crawled under it; the fourth-the captain-was only able to get his upper body under the shield.” He was seriously burned. Two other Los Angeles crews suffered smoke inhalation after they were forced to drive through the red wall of flame. A subsequent internal review by the two fire departments narrowly, and probably unfairly, focused on the role of “inexperienced leadership” in the near catastrophe, while ignoring the larger issue of house-by-house deployment under dangerous firestorm conditions.

Indeed, a growing risk of entrapment and death is inevitable as long as property values are allowed to dictate firefighting tactics. The exponential growth of housing in foothill firebelts, moreover, increases the likelihood of several simultaneous conflagrations and stretches regional manpower reserves to their limit, or beyond. As one national forest official observed:

These fires in Malibu prove that you could throw in every firefighter in the world and still can’t stop it.

Most experts agree that the most effective way to curb the rising fire danger is regular “prescriptive burning” every five to seven years to reduce fuel accumulation. This return to Tong-va practice, however, has proved almost impossible to implement in Southern California, outside of unpopulated national forest jurisdictions. All controlled burns entail some small risk of runaway fire, and local fire departments are understandably intimidated by their potential liability. Hillside homeowners’ associations, moreover, vehemently oppose prescriptive burning because of the belief that “blackened hillsides and ash in the swimming pools reduce property values.” In a typical case, the Los Angeles County Fire Department was recently sued by a Topanga Canyon resident who claimed that controlled burns would make it impossible to sell his home.

Mountain homeowners also continue to reject any special fiscal responsibility for the defense of their precarious habitats. Pennypinching Malibuites, for example, have resisted every effort to force them to update their notoriously inefficient water system or widen their narrow, winding streets. Yet thanks to their disproportionate political clout, they continue to expect that the general public will bear the exploding costs of a scientifically discredited strategy of total fire suppression. As Alan Kishbaugh, the president of the powerful Federation of Hillside and Canyon Associations of Los Angeles (which includes Malibu affiliates), recently put it:

We’re sitting here in our homes, doing our part, and expecting the best protection available…. When it comes to fire protection, Californians are entitled to the best that exists.

As in the aftermath of each previous fire tragedy, homeowners have invariably been seduced by the idea of a technological fix to the problem of wildfire ecology. The latest fetish is the CL-415 “Super Scooper”: a gigantic amphibious aircraft capable of skimming the surface of the ocean and loading up to 14,000 gallons of water per fire drop. For years the Federation of Hillside and Canyon Associations has been fiercely lobbying state and local officials to purchase a fleet of these Canadian-built planes at $17 million each. Since the 1993 evacuation of Malibu, moreover, the federation has enjoyed the support of the powerful West L.A. Democratic machine as well as most of the regional media, including the Los Angeles Times. In 1996 the state introduced the big planes on an experimental basis.

Once again, politicians and the media have allowed the essential landuse issue-the rampant, uncontrolled proliferation of firebelt suburbs-to be camouflaged in a neutral discourse about natural hazards and public safety. But “safety” for the Malibu and Laguna coasts as well as hundreds of other luxury enclaves and gated hilltop suburbs is becoming one of the state’s major social expenditures, although-unlike welfare or immigration-it is almost never debated in terms of trade-offs or alternatives. The $100 million cost of mobilizing 15,000 firefighters during Halloween week 1993 may be an increasingly common entry in the public ledger. Needless to say, there is no comparable investment in the fire, toxic, or earthquake safety of inner-city communities. Instead, as in so many things, we tolerate two systems of hazard prevention, separate and unequal.