In Venezuela’s Amazonas state, fishing has long been not just a trade but a whole way of life rooted in collaboration, knowledge sharing, and mutual aid. Now, under the U.S. blockade, fishing has become an even more important source of food. At the same time, the cooperative way of working of traditional fisherpeople has proven useful in solving blockade-induced obstacles.

The following study looks at the Ayacucho Commune, which is based on fishing and located in Amazonas’ capital city, Puerto Ayacucho. The Ayacucho Commune is an expression of the impressive synergy between a longstanding cooperative way of life, on the one hand, and a nationwide communal movement aimed at socialism, on the other.

The Ayacucho Commune comprises both Indigenous and criollo (non-Indigenous) fisherpeople. Their stories in this three-part series shed light on how fisherpeople are working together to build self-government and break their dependency on the capitalist market, while promoting food sovereignty in the region. In part I the communards explained the history of their commune and talked about their trade. Here, in part II, the fisherfolk talk about their collective practices and the challenges they face.

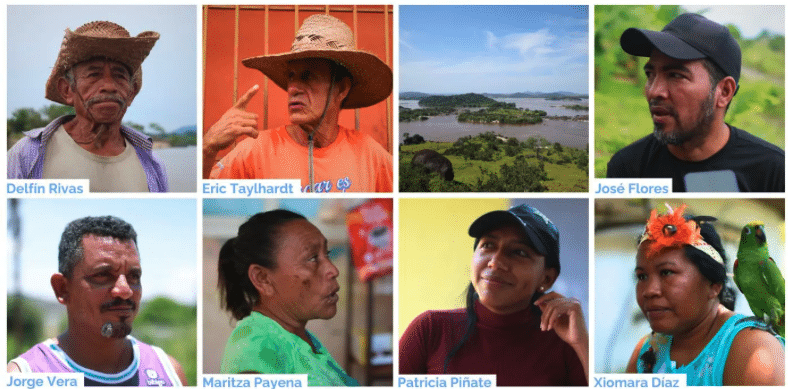

Delfín Rivas is a 73-year-old fisherman and a promoter of the CONPPAs (fisherfolk councils) | Eric Taylhardt is a housing spokesperson for the Ayacucho Commune and a CONPPA member | José Flores is the state coordinator of fisherfolk for the Ayacucho Commune | Jorge Vera is a fisherman and participates in the Bagre Communal Council | Maritza Payena is a fisherwoman and a spokesperson for the Bagre Communal Council | Patricia Piñate is a spokesperson for the July 5 Communal Council | Xiomara Díaz is a spokesperson for the Ayacucho Commune and UBCH (local PSUV structure) leader. (Photo: Rome Arrieche)

Fishing along the Orinoco River (continuation)

The anecdotes told by Ayacucho communards treat various aspects of their craft and of a mode of life deeply intertwined with the river.

COLLECTIVE PRACTICES AND NATURE

Xiomara Díaz: In the past, before the blockade, each person had a boat and even a motor. However, as the crisis deepened, much of the equipment deteriorated. And so we returned to more collective forms of organization. We joined forces to maintain boats and motors and we shared—and continue to share—some of our fishing instruments.

For example, in my CONPPA [Fishers’ Council], there are 30 members but only 15 boats. To address this, we established a rotation system. The motor operators, however, remain permanently linked to the boats since navigating the river—especially one as challenging as the Orinoco—requires skill and experience.

Eric Taylhardt: The curiaras, which are traditional boats carved from a single tree trunk, were used by our parents and grandparents. Many still rely on them today, particularly now that the crisis has rendered some of our bongos [self-built metal boats] unusable.

The process of making a curiara was always a collective one. Fisherfolk would come together to share tools and knowledge. Later, with the introduction of sheet metal, many transitioned to building bongos. These boats are also crafted by fisherfolk themselves and are also typically built through collaborative efforts.

José Flores: Just as we look out for one another in our community—ensuring that a neighbor returns home safely after a long night fishing—so we also care for nature.

Nature is generous, and we must be generous in return. What we take from the river isn’t for our benefit alone; it’s meant to be shared. On a good fishing day, we keep some fish for our household, sell some, and often give some away to those in need. In our community, and in most fishing communities, if you approach fisherpeople, they will always be willing to share part of their catch.

The river brings us together. In the best way, the Orinoco casts a net over our community, bringing us together.

We learned to respect the river from our parents, but Comandante Chávez also did his part: the 2001 Fishing Law banned indiscriminate fishing, which was key to ensuring sustainability. The law also bans trawling, which is a devastating method practiced by large-scale capitalist operations. In short, the law ensures sustainability and paved the way for the creation of fisherfolk councils, which we now know as CONPPAs.

The curiara is a dugout canoe. (Photo: Rome Arrieche)

FISHERFOLK COUNCILS (CONPPAS)

José Flores: The organization of the working class is at the core of any revolution, and ours brought councils to the barrios, to the campo [countryside], to the factories, and also to fishing communities.

In 2008, Chávez began to promote CONPPAs [Fisherfolk and Fish Farmer Popular Power Councils] as counterparts to the communal councils in fishing communities.

If the communal council is the place where we tackle problems such as infrastructure or services, the CONPPA is there to address the matters that specifically concern fisherpeople and their economic activity. Just as with the communal council, the decision-making body in a CONPPA is the assembly. At the same time, the law establishes channels for receiving financial and technical support from the government.

That said, the blockade has severely limited resources, so we haven’t received funding or loans for our activities in years. However, there are signs this may soon change.

At the state level, a program operates in coordination with the CONPPAs, delivering essential goods to fishers—a CLAP of sorts for the fishing sector. However, challenges persist, such as maintaining our bongos and motors, or lacking cold storage facilities, which forces us to rely on exploitative intermediaries.

Despite these obstacles, we know that solutions lie in collective work. In most CONPPAs, boats, and motors are maintained and rotated among members. We know that the CONPPAs and the five-commune Communal Circuit will help us all. ¡Solo el pueblo salva al pueblo! [Only the pueblo can save the pueblo!]

Eric Taylhardt: In the Ayacucho Commune, there are six CONPPAs. Each is formed through free association within the communal councils, which in turn make up the commune. However, the relationship isn’t always one-to-one. For example, one communal council may host three CONPPAs, while others might have none.

I returned to fishing in 2016, because the blockade left me with no other choice. Returning to my family’s trade helped me survive. I later joined the CONPPA, because it’s always better to struggle collectively. Together, we identified critical bottlenecks in our production, such as the lack of a refrigeration chain, and we’ve been steadily working to address them.

The nets and the catch. (Photo: Rome Arrieche)

INTERMEDIARIES

Maritza Payena: The capitalist middlemen are a scourge on our community. They take advantage of our precarious situation, especially during the ribazón [peak fishing season]. Recently, when the bocachico ribazón came, intermediaries from out of town paid us 1,500 Colombian pesos per kilo—equivalent to 15 bolivars [about 40 U.S. dollar cents at the time]. Then they resell it for 8 dollars per kilo to another intermediary, who sells it for 10 dollars or more per kilo in other states.

This endless chain of speculation keeps driving up the price. It must be broken.

Delfín Rivas: Intermediaries are a real problem. They’re the ones with the capital to buy, store, and transport the fish, while we only have our boats, nets, and hands.

They pay us next to nothing for our hard work. But since we don’t have storage facilities or refrigeration, we’re forced to sell to them—especially during the ribazón. Without a refrigeration chain, we remain dependent on them.

Jorge Vera: Just buying the fishing line to make or repair a net costs at least 90 dollars. During the worst of the crisis, a liter of gasoline for the motor was four or even five dollars. These are steep costs for us.

Sometimes we’re forced to turn to intermediaries for loans to cover these expenses, or even to get the fuel we need to fish. While it’s true that these loans allow us to keep going, they come at a high price. The middlemen pay us very little for our catch and then resell it at exorbitant markups.

Eric Taylhardt: The solution to the problem of intermediaries lies in the Communal Fishing Circuit establishing a fisherfolk-owned refrigeration chain infrastructure. This includes a cold storage facility and a refrigeration truck.

But the refrigeration chain isn’t the end goal; it’s just a critical first step. With this infrastructure in place, we can break our dependence on capitalist intermediaries while promoting local fish consumption. Our vision is to create a network of community fish markets across the communes of Puerto Ayacucho, where we can sell our catch directly at prices lower than the current market rate.

That’s our plan—an integral solution that addresses both production and distribution while making the catch available to working people. We’ve approached several institutions to request funding, whether through a loan, grant, or construction materials. We’re hopeful we’ll receive support soon because this is urgent.

SOVEREIGNTY

José Flores: Fishing is more than a livelihood for us—it’s a way to defend our country’s sovereignty, especially in the face of the U.S. blockade. The blockade has made it harder to access essential supplies like nets and fuel, but it has also pushed us to organize and develop solutions together.

Delfín Rivas: The blockade affects everything, from the rising cost of implements to the scarcity of basic goods, but it also underscores the critical importance of food sovereignty.

When we go out on the river, it’s not just to feed our families, it’s to ensure that our community—and our country—has access to healthy food. Fishing under these conditions is not easy, but it’s essential work that ties us to the broader struggle for dignity and food sovereignty.

The bongo is a boat made out of metal sheets. (Photo: Rome Arrieche)