In October 2023, India witnessed the judicial declarations over abortion laws and pregnancy move back and forth. In the case of a 27-year-old woman, married with two kids, she was denied the termination of her twenty-four week pregnancy on account of not qualifying for the legal abortion exceptions for sexual assault, fetal abnormality, mental illness, threat to her life, or being pregnant during a humanitarian crisis.1 Even though the doctors had clinically recognized at risk for postpartum depression and a harm to herself, she was refused the right over her own body.

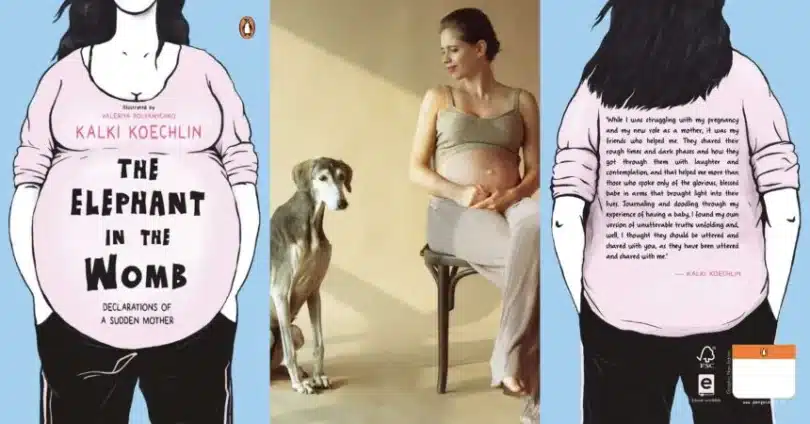

This is one of many cases where a woman’s reproductive rights end up becoming a topic of debate and discussion for the larger community. Similar stories unfold within the walls of homes, in every corner of the world, and seldom are discovered or move beyond family units and close social circles. Biographical narratives, memoirs, documentation, and journals assume critical urgency in times of social crises. As Kalki Koechlin illustrates in The Elephant in the Womb, it is only through talking, expressing, and sharing lived experiences that the world might tread in the direction of respecting and valuing women’s needs.2

Koechlin’s book and biographical note is a crucial text in the discourse, presenting a real and uncensored picture of pregnancy that showcases the way a pregnant woman’s body is positioned between the public and personal threshold. While the text provides several unfiltered perspectives on pregnancy, the privileged standpoint of the author must be acknowledged when analyzing the text.

The vantage point that the text emerges from limits a first-hand understanding of the experiences of the less privileged, but at the same time adds to the critique of the dehumanizing and alienating systems that affect pregnant women irrespective of relative social status. When accessing the social determinants of health—namely education, health financing, access to care, and adequate and trained healthcare workers—severe disparities between the less privileged and more affluent sections of the population become glaringly apparent.3 Acknowledging these disparities, it is no surprise that there exists a scarcity of narratives from less privileged classes. Historically, women have been taught to internalize fertility and maternal pain as divine blessings. The glamorization of motherhood adds to the societal pressure to appear grateful, leading women to shy away from expressing themselves. It is rare for the documentation of pregnancy to be uncensored.

Prevalent social discourses over the years have normalized the physical pain related to menstruation and pregnancy. It is expected of women to enjoy the process of childbirth, reveling in the bodily discomfort and “enjoying the period of pregnancy.” To complain of unease and discomfort, to express discontent during pregnancy, is often looked at as ungrateful or shameful.

Conversations surrounding pregnancy are largely limited to childbirth and childcare. A body that undergoes pregnancy is often bifurcated along the lines of postpartum and pre-conception. This subsumes the woman under the role of the mother, overlooking the mental and physical changes to the body, identity crises, and a sense of loss of selfhood. The ability to reproduce reduces the body of the woman to a “machinery” in constant need of surveillance, control, and external aid at the hands of medical institutions and social units.

In her book, Koechlin describes feeling helpless, mindlessly scrolling the Internet for help with her changing body and mind. Women experiencing pregnancy often express a similar sense of helplessness and loneliness, resorting to self-help and research to formulate an understanding of the maternal journey. In a 2014 article on women seeking information during pregnancy, evidence showed that these patterns of information-seeking are often shaped by the societal demand for a socially sanctioned “good mother.”4

The mother’s expression of identity becomes actualized through her nursing body, as Julia Kristeva discusses in her 1977 essay “Stabat Mater,” highlighting the process of alienation a woman feels from herself.5 The cyclical nature of maternal care often superimposes a distance on the identity of the woman from her idea of selfhood, caught between being and performing the role of the mother.

Health institutions, backed by medical knowledge systems, often claim a say over the conduct of a woman and mother, often dismissing her own physical and psychological needs. Even though trends in recent years point toward the potential for public health systems to be more inclusive and sensitive toward the concerns of pregnant people and help create safe spaces to enable them to voice their concerns, there is still a long way to go.

Women often find themselves stuck in a web of varied maternal practices based on medical science, recommendations by public health knowledge centers, social groups, and others’ experiences.6 As narrativized in The Elephant in the Womb, options like clinical birth, water birth, or home birth, doulas and family nurses are available to women, but the authority to choose a path best suited for herself often is not. In other cases, it is the lack of knowledge regarding these options that prevents them from making an informed decision. The dozens of biographical instances of this in the book lets readers into the world of confusion and fear that engulfs countless women.

It is important to acknowledge that this study focuses specifically on the experience of cisgender women’s pregnancy journey, recognizing that motherhood extends beyond biological parameters. Through a close textual analysis of the book, alongside relevant case studies and contemporary examples, this essay aims to understand how narratives of pregnancy are constructed, challenged, and governed.

Deconstructing the Elephant in the Womb

The Elephant in the Womb, Koechlin’s book on her pregnancy journey, is subtitled Declarations of a Sudden Mother. It opens with declarations and assertions along with confusion and confrontations. The text also includes illustrations along the margins and across the pages to drive the points home. The visual representations of the parts of the body, bodily changes, and the process of childbirth challenge the censored and sanitized portrayal of pregnancy in India.

The text opens not with the conception of a baby, but with the complexities associated with abortions. A nervous Koechlin remembers sitting in the gynecologist’s office and being asked if she is married. She recalls feeling ashamed, being subjected to social policing and scrutiny. Even though abortion is “one of the most common gynecological experiences,” it affects people, societies, and mothers differently.7 Through abortion laws, medical institutions, and educational facilities, the various power systems regulate and control the bodies and choices of women all over the world. Michael Foucault’s concepts of biopower and medical surveillance are useful here for providing a critical framework through which to examine the ways in which reproductive bodies are regulated and controlled.8 L. M. Comeau’s assertion that motherhood is an inherently political site, disciplined through medical surveillance, further elaborates the play of these power dynamics.9 Capable of reproducing a new generation, Foucault’s panopticon gaze imposes disciplinary power over pregnant bodies. This discussion is timely in light of the 2022 overturning of Roe v. Wade, the U.S. constitutional right to abortion, which sparked discussions about reproductive rights around the world. This overturning reflects the various power structures at play that regulate, control, and assert dominance over not only the body of the woman, but also her decisions about her body. The volatile nature of laws and rights meant to protect women and their agency hints at the illusion of gender parity in the modem world.

Koechlin’s experience with abortion pivots to the various approaches to pregnancy, often driven by societal pressure and compulsions rather than the mental, physical, and financial well-being of the mother. The concept of family planning is reserved for those lucky enough to be surrounded by support systems. The information around maternal care and well-being, reproductive choices, and pre- and post-natal care in India is stratified along the lines of class and caste.

In Of Woman Born (1976), Adrienne Rich distinguishes between two understandings of motherhood: a woman’s relationship to her own reproductive organs and capabilities and to the child she may or may not bear, and her relationship to the power institutions that aim to make sure the maternal potential of a woman is utilized to the maximum.10 It is this distinction that Koechlin’s memoir focuses on—the role she has chosen for herself and the fulfillment of that role that the medical and social institutions try to govern. It is in between these two definitions of motherhood that the woman disappears.

After her discussion of abortion, the book engages with miscarriage. Koechlin points out the folly in the word miscarriage, which implies a failure on the part of the woman. In her study on miscarriage, Victoria Browne shows that miscarriages are still commonly “understood to be something that could ‘discredit’ or embarrass the miscarrying/unpregnant person if revealed.”11 Disapproval and discomfort around discussing miscarriage also tend to shame and blame the woman. Sian Beynon Jones describes study how medical institutions often believe that, compared to middle-class women in “stable relationships,” working young women are less capable of birthing and raising a child.12 This adds to the patriarchal system of inequality that affects women to differing extents based on class, age, and caste.

The Elephant in the Womb also delves into contraceptives and the onus of contraception that lies largely on women. The availability and choices of contraceptives is extremely gendered. While there is an assortment of various contraceptives for women that heavily alter and affect their physical and mental health, men largely depend on only two options: external condoms and vasectomies. Women’s bodies often end up becoming sites of clinical interventions, affected both by the decision to avoid pregnancy and to carry a pregnancy. A study by T. K. Sundari Ravindran and P. Balasubramanian documents that many women, instead of availing the options of contraceptives, undergo induced abortions, pointing not to a lack of knowledge about safe sex, but an absence of sexual and reproductive rights.13 The power imbalance in relationships often forces women to bear both the physical and mental strains of reproductive control.

Particularly striking is the way that Koechlin’s memoir explores how women’s bodies seem to disappear behind the role of the mother. When expressing the experience of pregnancy and childbirth, the book engages with metaphors and comparisons, often anthropomorphizing different body parts or drawing parallels to various animals. The reason behind a change in the idea of self and a loss of unified identity can be attributed to the way “women are faced by the realities of motherhood in juxtaposition with their ideals of motherhood.”14 The process leading up to childbirth can be such that it often does not find justified vocabulary from the perspective of the mother. Medical descriptions abound, but they lack a subjective approach to childbirth. The metaphorical language employed in the book aids Koechlin’s descriptions and pregnancy experience.

The comparison to a whale is particularly striking in the way it vividly conveys a sense of loss of control over one’s body. Koechlin’s describes herself as a whale stranded on the beach, the gravitational pull making it collapse under its weight. Further in the book, she mentions feeling like a cow, milked on a schedule and discarded afterward. The description reduces her to a timed machinery, mechanical in nature. In a study examining the experience of pregnancy with expecting respondents, pregnancy was described as something “out of the ordinary, when the body apparently slips its moorings and refuses to ‘obey’ in the commonplace ways.”15 The second half of the text is written by Koechlin’s partner, who resorts to describing her as a “raging dragon.” The choice of imagery of the pregnant woman as a dragon is mythic, surpassing the understanding of reality we are in. It reflects the behavioral changes and mood shifts that often accompany motherhood’s hormonal upheaval. Koechlin’s text describe these changes by relying on animal imagery to best articulate the experience of distancing from the idea of self. The animal imagery is also reflected in the title of the book—The Elephant in the Womb—signaling the magnanimity of change and a journey of significant bodily transformation and psychological negotiations.

Alongside the descriptions of the experience of pregnancy, the book also highlights the way women are desexualized through motherhood. Koechlin’s experience of an undermined sense of sexuality comes from her disappointment with the fashion industry. She notes that there seems to be a lack of investment in stylish clothes for pregnant women. Instead, there seems to be a trend of shapeless, loose pieces of cloth tied with a belt at the waist, devoid of individual expression. The world takes it upon itself to provide comfort to the body of the mother at the cost of desexualizing the woman behind the role. This crisis in sexuality and sexual well-being transcends pregnancy into the postpartum period. Conversations around the sexual health of the mother are absent, particularly in India. In a study about postpartum morbidity in less developed countries, it was observed that maternal morbidity “continues to remain a neglected area despite the fact it not only adversely affects women’s physical, mental and sexual health but also may have serious implications for social and economic wellness, self-esteem and body image.”16 Koechlin observes that it might be because the crisis relates to the body of the mother and not the health of the newborn child. Many women also dismiss a decline in sexual needs as an aftermath of childbirth and an inevitable result of becoming a mother. These vulnerabilities relate to body image, sexual needs, and a woman’s sense of self, pitted against the societal and cultural expectations to prioritize the newborn, which often discourages women from looking out for themselves, seeking help, and expressing their concerns.

Maternal support and the shared experience of birth givers across generations end up being the ultimate help for new mothers. It validates the experience that women often aren’t able to express or find the right vocabulary to document. Collective vulnerability provides the strength society frequently overlooks or dismisses as emotional excess. As Koechlin writes, the duality of feeling like “the luckiest person alive” and simultaneously “speeding down a highway chased by a hurricane” captures the paradoxes of the maternal journey, highlighting its complexities, both beautiful and messy.

Conclusion

The need for discursive texts like Koechlin’s memoir emerges in the light of dialogues around bodily autonomy and women’s reproductive rights. Foucault’s concept of medical surveillance and Rich’s distinctions of motherhood help us understand the narrative that emerges from the text. The book critiques the sanitized and glamorized portrayal of pregnancy, governed by internalized patriarchy and situating the maternal body as a piece of machinery for reproduction.

Koechlin’s text is personal, but her experience of navigating pregnancy through power dynamics embedded in the state’s social fabric is universal. The text disrupts the normative discourses of pregnancy that reduce it to maternal joy and glory. Using metaphorical language and illustrations, the book deconstructs the mythic idea of motherhood. It reveals pregnancy to be an experience of negotiation of part of the woman, navigating identity and bodily crises, irreversible changes to the idea of self, acceptance, rejection, and dejection of parts of the process.

The Elephant in the Womb is important in the way it demands a reimagining of motherhood—one where the woman’s agency is realized, where she is just as important as the child she bears and the mother she becomes. It asks for its readers to understand the way power works through medical institutions, society, and familial structures limiting the movement of a pregnant body in arenas of personal choice. It highlights the importance of support systems, of similar experiences and their documentation, of a need to extend support through strata of class to women everywhere. Koechlin’s book is a critical reflection and an interrogative dialogue, navigating the complex terrain of pregnancy and motherhood.

Notes

1. “Abortion Law in India: A Step Backward After Going Forward,” Supreme Court Observer, November 17, 2023.

2. Kalki Koechlin, The Elephant in the Womb, illustrations by Valeria Polyanychko (Gurugram: Penguin Random House India, 2021).

3. 3) Minal Madankar, Narendra Kakade, Lohitha Basa, and Bushra Sabri, “Exploring Maternal and Child Health Among Tribal Communities in India: A Life Course Perspective,” Global Journal of Health Science 16, no. 2 (January 2024): 31.

4. Deborah Lupton, “The Use and Value of Digital Media for Information About Pregnancy and Early Motherhood: A Focus Group Study,” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 16, no. 1 (2016): 240.

5. Kelly Oliver, “Tales of Love (1987),” in The Portable Kristeva, 2nd ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 137–79.

6. Marsden Wagner, “The Public Health versus Clinical Approaches to Maternity Services: The Emperor Has No Clothes,” Journal of Public Health Policy 19, no. 1 (January 1998): 25.

7. Anuradha Kumar, Leila Hessini, and Ellen MH Mitchell, “Conceptualising Abortion Stigma,” Culture, Health & Sexuality 11, no. 6 (2009): 625–39.

8. Molly Wiant Cummins, “Reproductive Surveillance: The Making of Pregnant Docile Bodies,” Kaleidoscope 13, no. 1.

9. Lisa M. Comeau, “Towards White, Anti-Racist Mothering Practices: Confronting Essentialist Discourses of Race and Culture,” Journal of the Motherhood Initiative for Research and Community Involvement (2007): 21.

10. Adrienne Rich, Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1995).

11. Victoria Browne, “How to Defeat Miscarriage Stigma: From ‘Breaking the Silence’ to Reproductive Justice,” Feminist Theory 26 (July 2024).

12. Sian Beynon-Jones, “Expecting Motherhood? Stratifying Reproduction in 21st-Century Scottish Abortion Practice,” Sociology 47, no. 3 (2013): 509–25.

13. T.K. Sundari Ravindran and P. Balasubramanian, “Yes to Abortion but No to Sexual Rights: The Paradoxical Reality of Married Women in Rural Tamil Nadu, India,” Reproductive Health Matters 12, no. 23 (January 2004): 88–89.

14. Elizabeth K. Laney, M. Elizabeth Lewis Hall, Tamara L. Anderson, and Michele M. Willingham, “Becoming a Mother: The Influence of Motherhood on Women’s Identity Development,” Identity 15, no. 2 (April 2015): 126.

15. Samantha Warren and Joanna Brewis, “Matter Over Mind?” Sociology 38, no. 2 (April 2004): 221.

16. Aditya Singh and Abhishek Kumar, “Factors Associated with Seeking Treatment for Postpartum Morbidities in Rural India,” Epidemiology and Health (October 2014).