The Huo̧ttö̧ja̧ people in Venezuela’s Amazonas state have long resisted colonization and proudly preserve their language. Today they are building communes that draw both on Chávez’s socialist roadmap and their ancestral ways of organization, including collective land tenure and assembly-based governance.

The February 4 Huo̧ttö̧ja̧ Commune, which is the focus of this testimonial work, sits on the edge of a savanna that gradually turns into rainforest and is crossed by the beautiful Parhueña River. While the majority of this commune’s population is Huo̧ttö̧ja, as indicated by the commune’s name, there are also Kurripakos, Jivis, Banivas, and a small number of non-Indigenous people.

The commune comprises 12 communal councils and a total population of about 2500, with the largest community being Limón de Parhueña, home to about 750 people. Some of the smaller communities that are tucked away in the rainforest preserve traditions such as living in churuatas [thatched buildings], and can only be reached by foot or motorbike. The most distant community in this commune, the Alto Parhuani Communal Council, is six hours away on foot.

In this three-part series, we listen to some of the men and women of the February 4 Huo̧ttö̧ja̧ Commune who share their knowledge about organizational practices, agricultural production, and forms of resistance to the US blockade. The first installment, presented below, focuses on the history and traditions of the Huo̧ttö̧ja̧ people.

[Part of VA’s Communal Resistance Series]

Juan Rafael Arana Pérez is the capitán of Limón de Parhueña | Juan Rumeno Pérez is the cacique of Limón de Parhueña | Nereo López Pérez is a popular educator and professor who works to preserve the stories of Limón de Parhueña; his Huo̧ttö̧ja̧ name is Inaru | Sirelyis Rivas is a spokesperson of the Limón de Parhueña Communal Council (Rome Arrieche)

The Huo̧ttö̧ja̧ people and their traditions

The Huo̧ttö̧ja̧ people are proud of their heritage and history of resistance. A dynamic society, they build collectively on these traditions within the dialectic of their changing culture.

Nereo López Pérez: We are the Huo̧ttö̧ja̧ people, the great great great grandchildren of Cacique Ähuänumä. Our ancestors lived in harmony with nature along the Raudal Guáramo: they hunted, fished, and gathered the fruits that nature provided. They also maintained conucos [subsistance plots], where they grew yuca to make casabe [flatbread] and mañoco [granulated flour]. Spiritually, we are also said to be the children of the Wajari – a powerful force revered by our ancestors.

Our elders were organized in a cooperative manner. They lived in large churuatas [thatched buildings] and the land and the production were collective.

Juan Rumeno Pérez: Our ancestors had a worldview deeply connected with nature. If a young man was bitten by a snake, he would be taken to the churuata for a ritual open only to the initiated. They used yopo, which is a hallucinogen, and they say that a vision would come to the wise man [shaman].

Beyond specific events like dealing with snake bites, the wise man’s advice would guide the community in daily life: how to avoid tigers and evil spirits, when to sow, and how to hunt. He knew how to communicate with the gods to minimize dangers.

Now, in Limón de Parhueña, we have a different religious practice: we are Christians and we pray to the Lord Almighty.

Taking fish home through the streets of Limón de Parueña. (Rome Arrieche)

SELF-GOVERNMENT & LEGITIMATE AUTHORITIES

Nereo López Pérez: The Huo̧ttö̧ja̧ people, along with many other Indigenous communities in Amazonas, have resisted multiple waves of colonization, and we are still standing. We speak our own language, have our own authorities, and practice self-governance – but this doesn’t mean we live in isolation. We are connected to the world and participate, holding on to our identity and history. Chávez and the 1999 Constitution gave us a voice, and we make sure that we are heard.

Juan Rumeno Pérez: My authority as one of the leaders in this community stems from our culture and history, but the authority of Indigenous leaders is also recognized in Venezuela’s Constitution [Art. 119]. However, as legitimate authorities, we are not separate from the community. We are part of it and must safeguard it. That’s why we work with the commune or any other social movement or organization in Limón de Parhueña.

But, you may ask, what happens if there’s a conflict in our community? What happens if there’s friction between two communal councils? We call in the parties, mediate, and try to foster an agreement that works for everyone. We are one community, and our conflicts have to be solved within.

Here our legitimate authorities are the cacique [pointing at himself], the capitán [pointing at Juan Rafael Arana Pérez], and the Council of Elders. In the time of our grandparents, the shaman was also an authority. When someone hunted an animal, it would be brought to him for a prayer ritual before it was eaten. Today, we are Christians, so those practices are no longer with us.

As the cacique of Limón de Paruhueña, I work closely with the capitán and the Council of Elders to solve problems. Together, we seek harmony.

Juan Rafael Arana Pérez: I was born in 1969, and my father, may he rest in peace, was the first legitimate authority [officially recognized] in Limón de Parhueña. As capitán, I work with the people to coordinate community efforts. My main responsibility is to ensure that essential tasks get done.

Juan Rumeno Pérez: The Council of Elders is also considered a legitimate authority. They are the ones who have lived longest and provide advice in complex situations. They are the community’s guide. We call them our “living books,” because their wisdom is linked to our history.

Nereo López Pérez: In the Huo̧ttö̧ja̧ tradition, the churuata is the heart of the community. Our grandparents lived collectively in large churuatas, which is also where the Council of Elders would gather and deliberate with the cacique, and where the assemblies would take place.

The churuata is also where our grandparents held the Warime, an ancestral ritual. The Warime could bring several churuatas [used here as a synonym for the community] together through its chants and dances, forging a bond between communities and nature.

In Limón de Parhueña, each family has its own home made of bricks and mortar, but the churuata remains the center of our community. While many things have changed, the churuata is still the heart of Huo̧ttö̧ja̧ life – the space where we hold assemblies and share stories.

Sirelyis Rivas: People often ask me what is a commune, and I tell them that a commune is an assembly, a space where people meet to find solutions to the problems they face. For the Huo̧ttö̧ja̧, this is nothing new. Working together is part of our history and our culture.

In the tradition we come from, there are the legitimate authorities – the cacique and the capitán – but the assemblies for deliberation, assigning tasks, and taking responsibilities are equally important. They are intrinsic to who we are.

Making mañoco, a coarse yuca flour. (Rome Arrieche)

“EL PLAN DE VIDA” [LIFE PLAN]

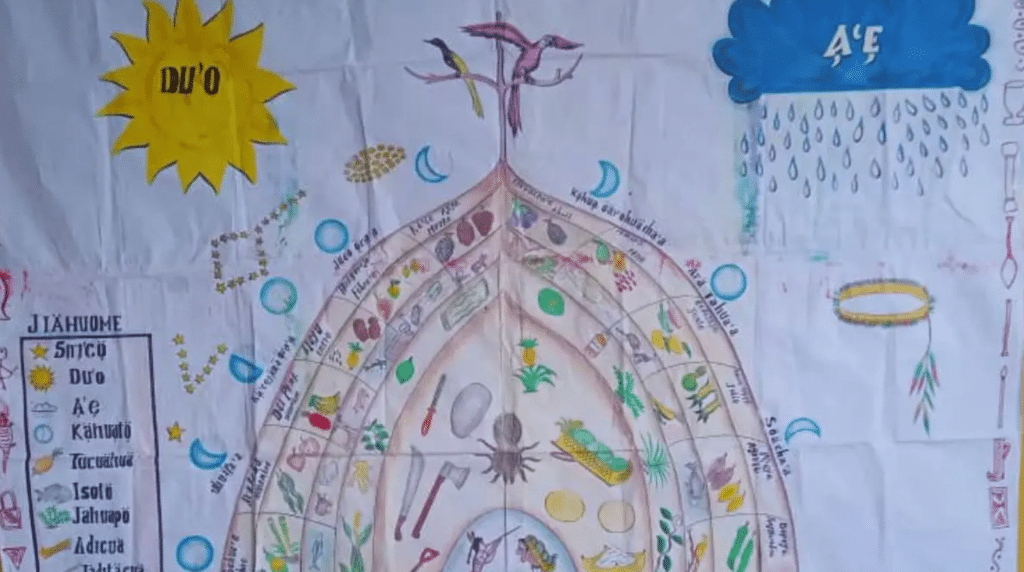

Nereo López Pérez: We have an ancient tradition of carefully passing knowledge from one generation to the next. It would be a bad omen for the community if an elder did not pass their knowledge to the younger generation. Today, a key piece of knowledge transmission is expressed in what we call the “Life Plan,” an initiative promoted hand-in-hand with the Ministry of Education.

Our Life Plan is divided into summer, the dry season, and winter, the rainy season, and we take into account the lunar cycles. It tells us when trees can be cut, when to sow, when to gather wild fruits, when to hunt, and when the ribazón [peak fishing season] might come.

The plan brings together ancestral knowledge that helps us live in harmony with nature. It also tells us where we can walk, and where we should not, because our ancestors lay there, how to prepare for the first menarche or a birth. The plan gathers the community’s knowledge and the advice of the Council of Elders. In Limón de Parhueña, our Life Plan is represented by a churuata.

The Life Plan is our calendar because it speaks of the cycles of life and helps us live in harmony with nature. But the plan also has profound implications. It represents a life that is well lived.

Life Plan (Nereo López Pérez)