This article was originally published in Chinese at Guancha.cn.

What are the real U.S. economic choices facing Trump?

China has set its economic growth target for 2025 at “about 5.0%”. That this can be successfully achieved, what is necessary to ensure it, and the implications for achieving China’s strategic goals to 2035, was analysed in an earlier article “China’s economy in 2024 continued to far outgrow the U.S.”. But the other key economy in the world, whose development has major implications for China is the United States. In particular Trump has set as his explicit goal speeding up the U.S. economy, and slowing down China’s. Given the U.S. tariffs, sanctions and other measures taken by the U.S. against China the comparative economic performance of China’s and the U.S. economies is a major factor for geopolitics and the situation facing China.

The aim of this, and a succeeding article, therefore, is to make the most precise analysis possible of the fundamental factors that will determine U.S. economic growth in the next period—and their interrelated geopolitical and U.S. domestic political consequences. This in turn, as will be seen, determines and is affected by the real, as opposed to illusory, choices which face the Trump presidency 2.0.

The real situation facing the U.S. economy as opposed to myths about it

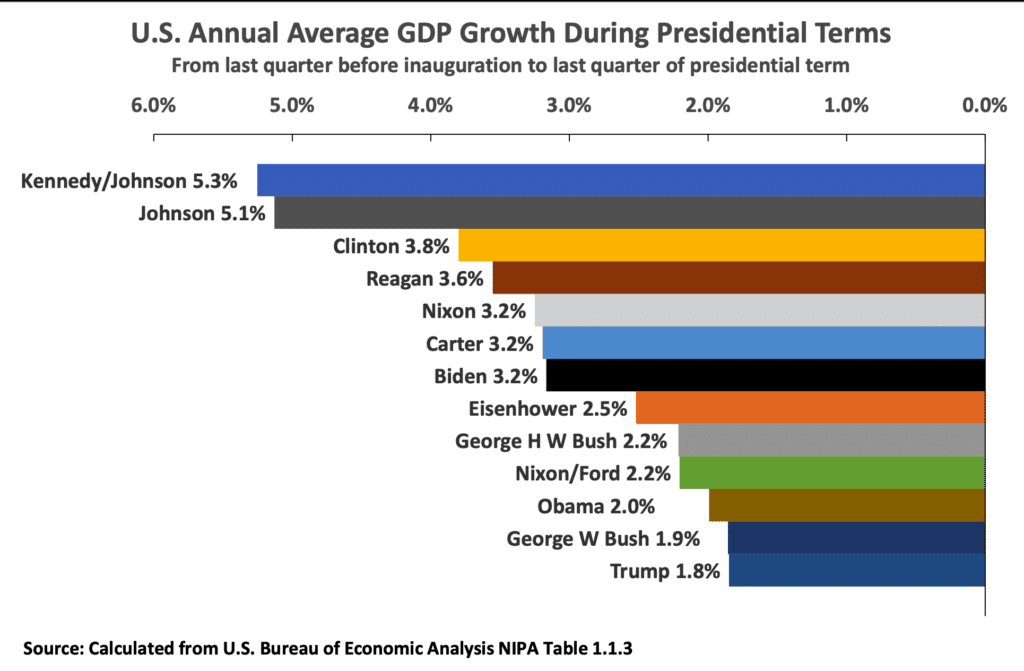

President Trump habitually misrepresents his own economic record. For example, at his 2024 presidential campaign rallies he repeatedly claimed that during his first term the U.S. had the “greatest economy in our history”. In reality, during his first term, the U.S. economy had the slowest growth during any post-World War II presidency (see Figure 1).

Serious Western analysts do not bother to hide their disbelief in these, and similar, fallacious claims. Thus, for example, Financial Times U.S. affairs editor, Edward Luce, wrote of Trump’s recent speech to Congress:

It is Mardi Gras in New Orleans. Yet no parade could match the carnival in Donald Trump’s Tuesday night speech to Congress… one could almost hear the remnants of the fact-checking community snap their laptops shut… It would be… futile to compare Trump’s address to any by his predecessors… This was in a category of one… Trump’s speech was a fever dream of extravagant promises. His pledge to cover America with a ‘golden dome’ modelled on Israel’s ‘iron dome’ would use up every gold bar in Fort Knox. A few minutes earlier, Trump had promised to balance the federal budget. Was his pledge to take Greenland ‘one way or another’ a threat or a fantasy? Ditto for the Panama Canal… when historians look back on March 4 2025, his speech might barely rate a footnote.

Discussion in some sections of the media about the Trump presidency also frequently primarily focuses on speculations about his subjective intentions, or what he would like to achieve in a second term, or belief that some short term superficial measure by Trump could substantially speed up the underlying growth of the U.S. economy—as will be seen this is entirely untrue.

Both such approaches are unhelpful when assessing the practical choices possible for Trump: these are not determined by what Trump wants, or by his unreal propaganda claims, but primarily by the objective situation of U.S. politics/geopolitics and the U.S. economy and the interrelation of forces within this.

Making such an analysis of the objective situation facing the U.S. economy, in turn, requires as precise quantitative analysis as possible of the most powerful factors affecting the U.S. economy and their consequences for U.S. politics and geopolitics. The terms “systematic” and “accurate” are stressed here, as any analysis which focuses merely on a single Trump policy does not deal with the consequences of the fact that the U.S., as with every economy, forms an interlinked whole—any changes in one aspect of the U.S. economy therefore have consequences for, and are affected by, its other aspects. To be accurate, in turn, it is necessary to study in quantitative terms the interrelations which exist between the major determinants of U.S. economic performance.

To do this the author, therefore, gives below a great deal of precise quantitative data on the situation of the U.S. economy—and does not apologise for doing so. The situation of the U.S. economy, and its geopolitical implications, is one of the most important factors in the world—including for its consequences of China. It is therefore necessary to analyze the fundamental forces driving this in as much detail, and with the greatest accuracy, as possible—exaggeration or inaccuracy in any direction, “optimism” or pessimism”, is not helpful and is potentially dangerous in such a serious matter as the dynamics of the United States. “Seek truth from facts”, in the field of the economy, requires precise numbers not imprecise and vague generalities.

To deal with these interrelated issues this analysis is divided into four questions:

- What is actual situation of the U.S. economy, what are the domestic political consequences for Trump, and what are the geopolitical consequences, in particular as they affect China, that flow from that situation?

- What are the real steps that would be required to significantly increase the U.S. economic growth rate?

- What are the economic consequences of the policies Trump has chosen, and therefore can they succeed in significantly speeding up the U.S economy?

- What are the political and geopolitical implications of the economic means which Trump has chosen?

The first two of these questions are dealt with in this article, and the other two in the second article in this series.

Section 1—the immediate situation facing Trump

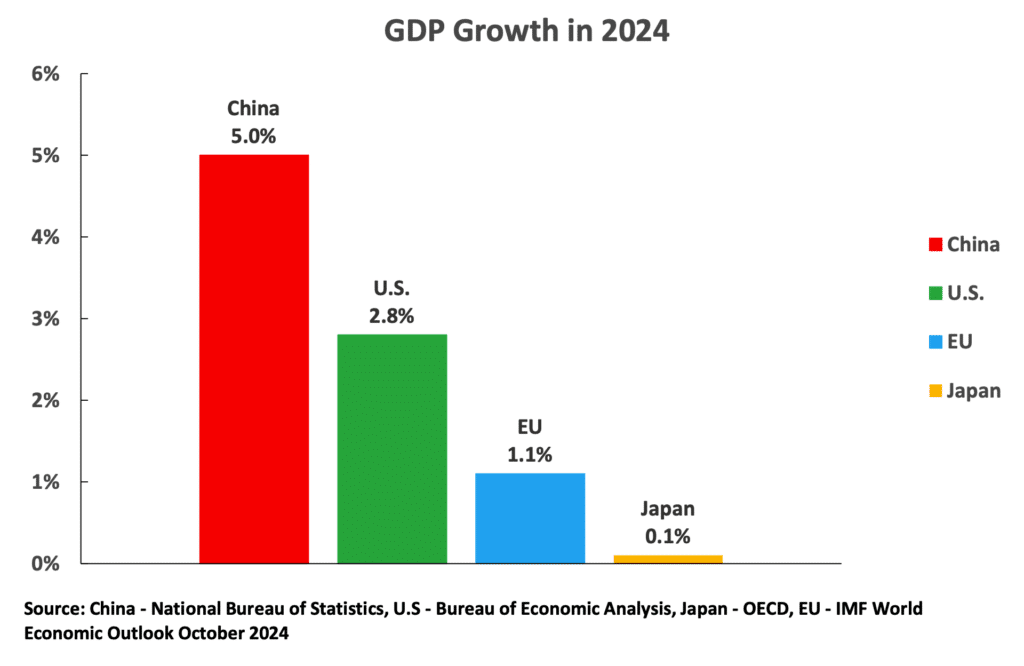

Starting with the immediate situation facing Trump. It is crucial to understand accurately the actual growth trajectory of the U.S. economy. Taking first the results simply for 2024, the U.S. economy grew by 2.8% while China’s economy grew by 5.0%—China’s economy grew 80% faster than the U.S..

This data alone highlights that much Western media during the last period served simply as propaganda rather than objective reporting. Statements from outlets like The The Economist, claiming that the U.S. is “leaving its peers ever further in the dust,” or from the Wall Street Journal describing China as having “a stagnant economy,” were either deliberate lies, propaganda distortions, or failures to investigate the facts. Regardless of the reasons for putting them forward these statements are purely misleading, and it is therefore rather disgraceful, and a sign of the real worth of claimed quality “journalism”, which turns out to be propaganda or failure to investigate the facts, that similarly inaccurate statements regularly appeared in the medias.

Current slowing of the U.S. economy—why China’s growth lead over the U.S. is likely to somewhat increase in 2025

The reason that “in the last period” is stated above is because much discussion in the U.S. media now focuses on the possibility of significant slowdown in the U.S. economy. The modelling at the time of writing of “GDP Now” by the Atlanta section of the U.S. Federal Reserve, the U.S. central bank, for example, predicts that in the first quarter of 2025 the U.S. economy will actually contract by 2.4% on an annualised basis.

Whether or not the U.S. falls into an actual contraction or merely slows in 2025 in line with its long term growth rate—and present trends, for reasons shown below, do not indicate why there should be any serious recession in the U.S.—is not crucial for the present purposes of analyzing medium/long term growth trends in the U.S. economy. But what is the case is that in 2023 and 2024, with growth respectively at 2.9% and 2.8%, the U.S. was growing above its long-term trend—which is slightly above two percent annual growth. This means that in 2025, if China achieves its “about 5.0%” growth target, the growth rate lead of China over the U.S. is likely to increase somewhat —to a greater or lesser degree depending on how significant the slowdown in the U.S. economy is. This would have some significant psychological effect on international perceptions of the two economies. It is therefore important to explain this situation internationally—with no exaggeration but simply as an objective presentation of the facts.

What is also clear, however, for reasons analysed below, is that attempts by Trump to raise the medium/long-term U.S. growth rate will inevitably lead to clashes with a series of other countries and also produce conflict within U.S. politics.

Broader international comparisons

Regarding broader international comparisons, a detailed analysis of China’s economic performance in 2024 compared to other countries, including the U.S., was made in “China’s economy in 2024 continued to far outgrow the U.S.”. Therefore, only the most important facts for analysing the international economic situation facing the U.S. are summarized here.

Figure 2, therefore, shows the data now available for GDP growth in 2024 for the major economic centres. China, the U.S.’s, and Japan’s GDP growth of 5.0%, 2.8% and 0.1% are actual results, while the EU’s 1.1% is the IMF’s projections for full-year growth based on the first three quarters results. Based on this data, as well as China’s 2024 GDP growth rate being 80% higher than the U.S.’s, it was four and a half times faster than the EU’s, and fifty times faster than Japan’s.

Looking at this international situation from the U.S. viewpoint, its economic growth was two and a half times faster than the EU, 28 times faster than Japan, but only 56% the rate of China. The objective situation facing the U.S. is therefore that its economic growth considerably exceeds its major Western competitors, the EU and Japan, but is far slower than China—it for this evident reason that the Trump administration will focus its attention on China.

Medium term economic growth performance

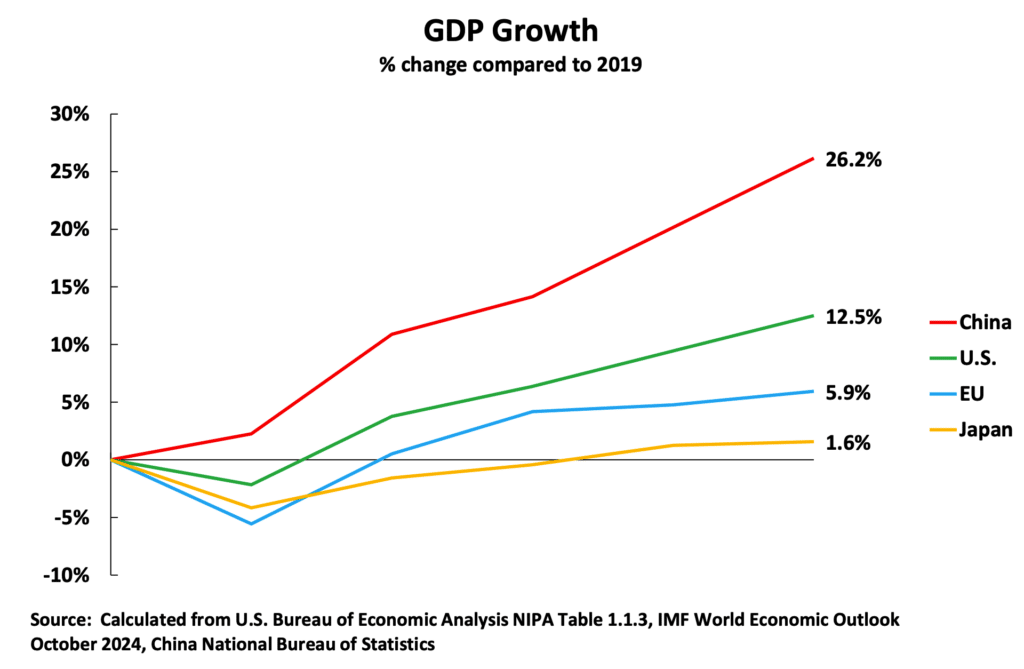

Even more clarificatory for judging trends, as it removes the effect of short-term fluctuations due to lock downs during COVID and recovery since, is to take the situation of the major economic centres during the entire period since before the pandemic. Figure 3 shows that in the five years since 2019 China’s economy grew by 26.2% and the U.S. economy by 12.5%, That is, in the period since the beginning of the pandemic the U.S. economy grew at only 48%, less than half, China’s rate.

This once more confirms that to close the economic growth rate gap between the U.S. and China, the Trump administration must therefore achieve one, or both, of two aims:

- The U.S. must slow China’s economy.

- The U.S. must accelerates its own economy.

Taking the first of these, the U.S. attempt to slow China’s economy, the means available to the U.S. to attempt to achieve this were analysed in detail in the previous article “China’s economy in 2024 continued to far outgrow the U.S.”. To seriously slow China’s economy the U.S., for reasons analysed in that article and briefly below, must secure a significant reduction in the percentage of net fixed capital investment in China’s GDP. However, unlike previous uses of this method, to force their economies to slow down, against competitors which were economically and militarily subordinate to the U.S.—Germany, Japan and the Asian Tigers—the U.S. has no way to compel China to adopt such a course. The U.S. instead has to rely on attempting to persuade China to commit economic suicide by voluntarily reducing its level of investment in GDP—the means used to attempt to persuade it to do so being economically fallacious arguments about consumption, as the previous article discusses.

As the issue of the most serious means by which the U.S. could attempt to slow China’s economy was analysed in detail in the previous article it is not dealt with further here. The present articles only deal with the issues involved in any attempt by Trump to accelerate the growth of the U.S..

That is, the question addressed in these articles, is whether Trump can decrease China’s lead in growth over the U.S. by speeding up the U.S. economy?

Political situation in the U.S.

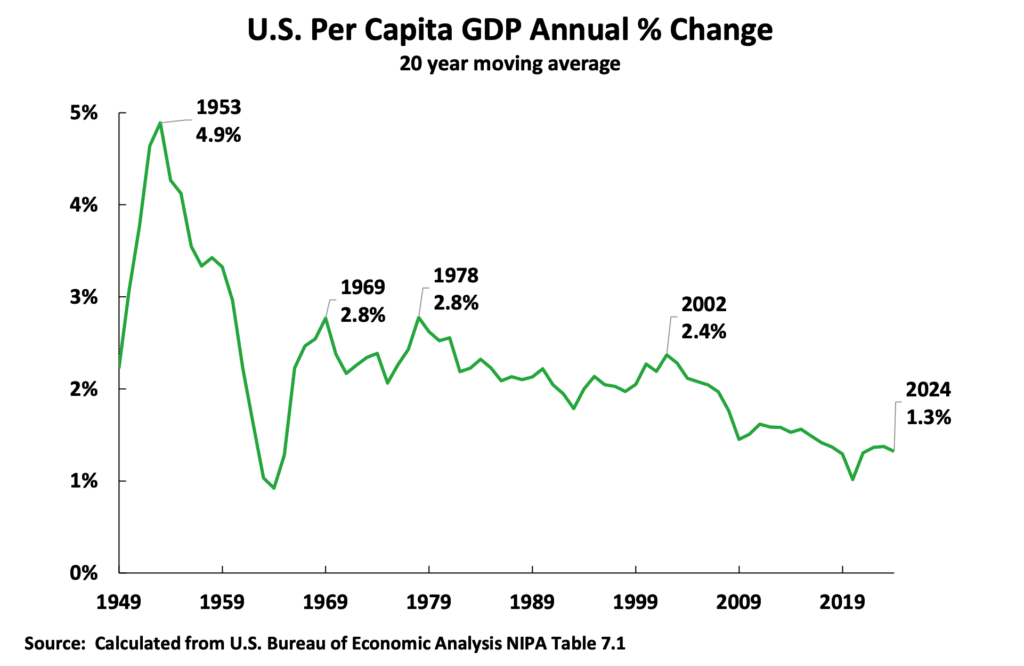

Turning to the implications of these U.S. economic growth figures for United States domestic politics, the reasons for Trump’s return to office, and therefore the political situation facing Trump, it is clarificatory to examine the trends in the U.S. economy in terms not only of total GDP but also per capita GDP—as per capita GDP is more closely related to living standards than total GDP.

Figure 4 therefore illustrates the long-term post-World War II trends in U.S. per capita GDP growth, using a 20-year moving average to smooth out short-term business cycle fluctuations. This shows a clear 70-year trend of declining U.S. annual per capita GDP growth—with this falling from 4.9% in 1953, to 2.8% in 1969, 2.4% in 2002, and 1.3% by 2024. This last figure is very slow, indeed bordering on stagnation.

Such a very slow rate of per capita economic growth necessarily fuels social and political discontent and instability in the U.S.. This has duly occurred with the increasingly bitter confrontations in U.S. politics during the first Trump term, the Biden presidency, and leading to the second Trump presidency—indices of this being the increasingly harsh rhetoric between the U.S. political parties, the physical attack on the U.S. Congress on 6 January 2021, the forced withdrawal of Biden from the presidential race 2024, the criminal cases started against Trump before the presidential election, the pardoning by Trump of large numbers of violent 6 January rioters, the rapid closing by Trump of entire government departments such as USAID on resuming the presidency etc. Unless the present slow growth of U.S. per capita GDP can be reversed it is impossible to stabilise the social and political tensions in the U.S. This, in turn, has major knock-on geopolitical consequences which affect China.

The U.S. economy under Biden—why Trump won the presidential election

More significantly still for understanding the U.S. social and political situation, is that an increase in U.S. per capita GDP only creates the potential for the possibility to increase living standards for the mass of the population. Whether this actually occurs depends on how that increase in GDP is distributed.

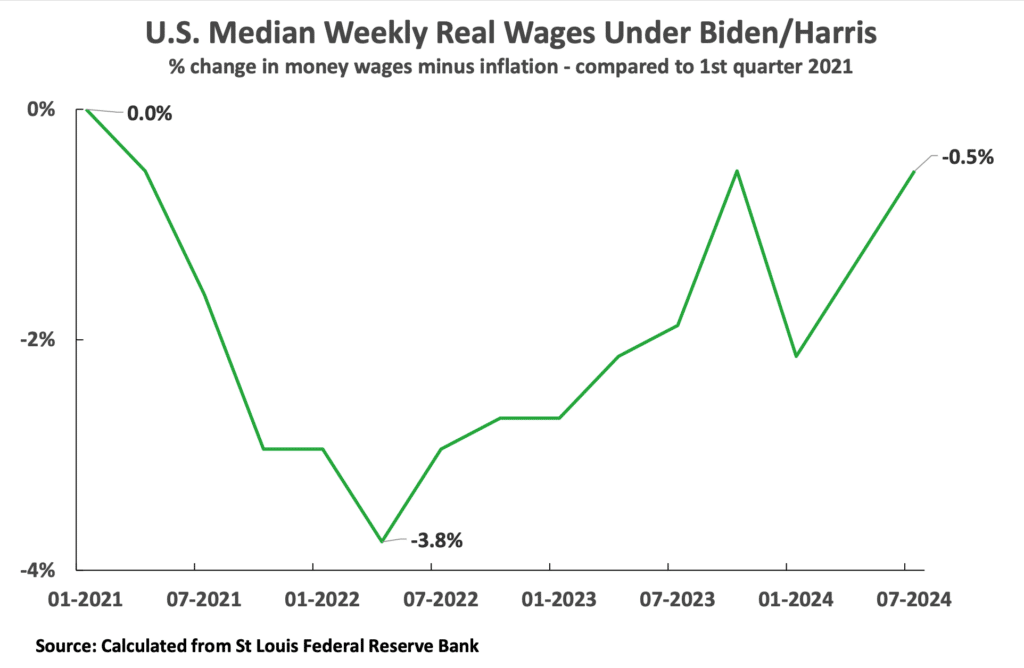

The data shows that In the U.S., in the recent period, the benefits of even the slow increase in per capita GDP which has been occurring did not go to the mass of the U.S. population—the statistics on this easily explain why the Democrats lost the election and why this was foreseeable in advance. During Biden’s presidency, up to latest available data for wages, which is for the third quarter of 2024, U.S. per capita GDP went up by 10.9%, but real inflation adjusted wages were actually lower than when Biden/Harris were inaugurated—see Figure 5. That is, American wage earners, who form the overwhelming majority of the population, became worse off under Biden.

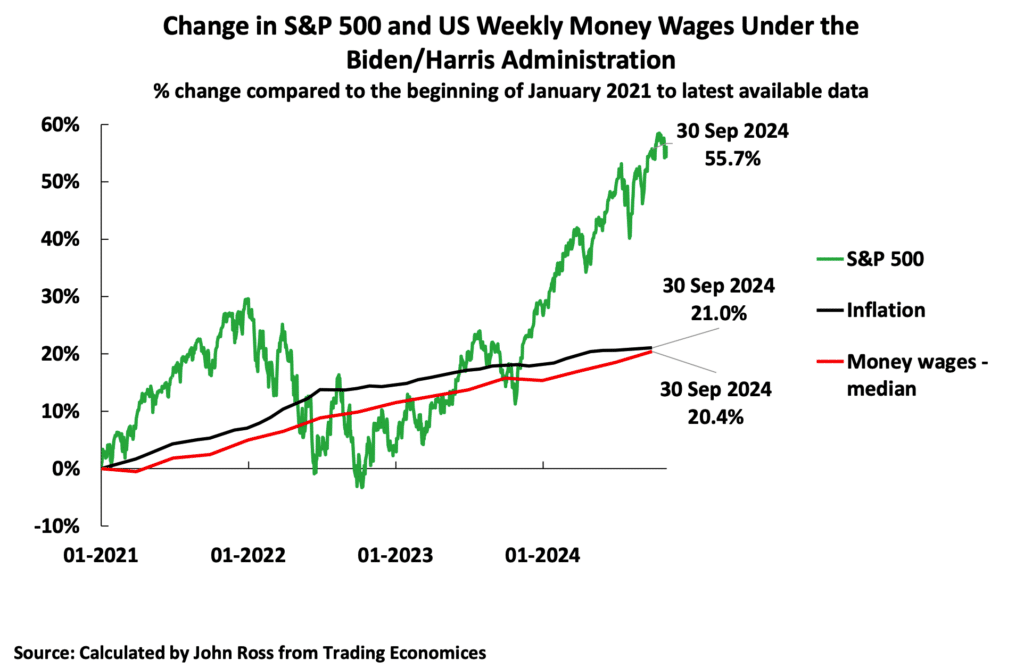

The facts show that the Biden administration carried out a redistribution of wealth from workers, the mass of the population, to owners of capital. Figure 6 shows that during the period of the Biden presidency, from January 2021 to the latest available data for U.S. wages, the S&P500 share index rose by 55.7%, inflation by 21.0%, but U.S. median nominal weekly wages by only 20.4%. That is, owners of capital made large gains in real inflation adjusted terms while wage earners, that is the mass of the U.S. population, became worse off—while simultaneously those able to live from income from capital, a small part of the population, became substantially better off. It is therefore no surprise that social and political tensions in the U.S. rose.

This trajectory under Biden therefore also shows what is likely to happen to Trump if he in turn cannot improve U.S. living standards. Social tensions will rise again, and Trump will become unpopular. It is therefore significant that Trump’s poll approval rating at the end of February, at 45%, was the lowest for any U.S. President, at that time in their presidency, since World War II except for Trump’s first term’s 42%—the historical average approval rating for U.S. president’s since World War II after their first quarter in office was 61%. By 16 February the number of those disapproving of Trump, 51%, was already higher than those approving at 45%.

Economic failure during the first Trump presidency

To complete the immediate picture, it was already noted that, contrary to Trump’s claims that his first presidency was a great economic success, the data shows clearly that this was untrue. Figure 1 above showed that annual average GDP growth during the first Trump presidency, at 1.8%, was the lowest for any post-World War II president. Trump may claim that this was due to the impact of Covid, which was certainly a factor, but the factual reality is that Trump has no track record as president of fast economic growth. The slow economic growth during the first Trump presidency (together with the extremely powerful Black Lives Matter movement following the racist murder of George Floyd in May 2020), was clearly the key factor in the defeat of Trump in the 2020 presidential election

The consequences of the very slow growth of the U.S. economy under both the first Trump presidency, and under Biden, therefore, confirms the socially and politically destabilising effects of the present situation of very slow U.S. growth, and for significant sections of the population decline of U.S. living standards. Unless this trend can be reversed, and U.S. economic growth accelerated, socio-political tension in the U.S. will persist and the Trump administration itself will become unpopular. Failure to understand this factual situation, to instead believe Trump’s self-serving propaganda, or to concentrate on speculation about his subjective intentions, therefore leads to an inaccurate understanding of the dynamics within the U.S.

For both economic and political reason, therefore, the decisive issue for the Trump presidency is whether it can accelerate U.S. economic development. Analysing what would be necessary to achieve this therefore forms the subject of the rest of this series of articles.

The slowing U.S. economy

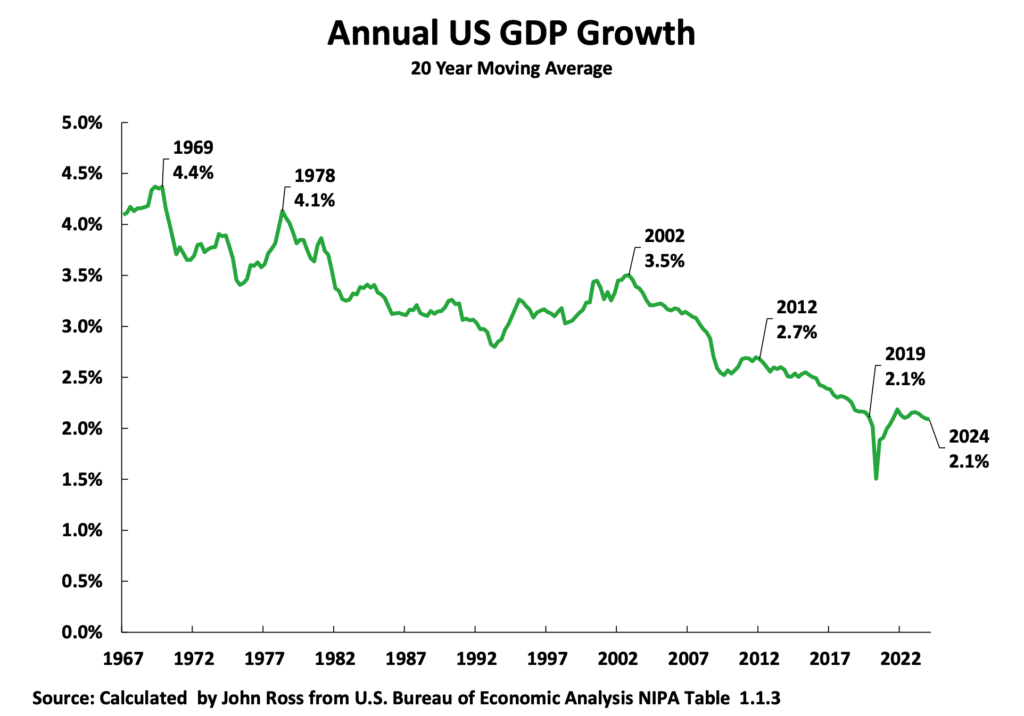

To initially assess how easy or difficult it is to speed up the U.S. economy, and the political and geopolitical consequences of this, it is necessary to consider long-term U.S. growth rates: these show the fundamental factors in the situation which are sometime obscured by purely short-term fluctuations. Figure 7 shows that U.S. annual average economic growth rates have been declining for almost 60 years. Taking a 20-year moving average, to remove the effect of short-term business cycle oscillations, U.S. annual average GDP growth fell from 4.4% in 1969 to only 2.1% by 2024—that is by more than half.

Clearly a process of economic slowdown which has been taking place for almost six-decades has extremely powerful roots. Only if Trump tackles these, therefore, can this powerful and prolonged slowdown of the U.S. economy be reversed.

Section 2—What is required to speed up U.S. economic growth?

What determines the speed of U.S. economic growth

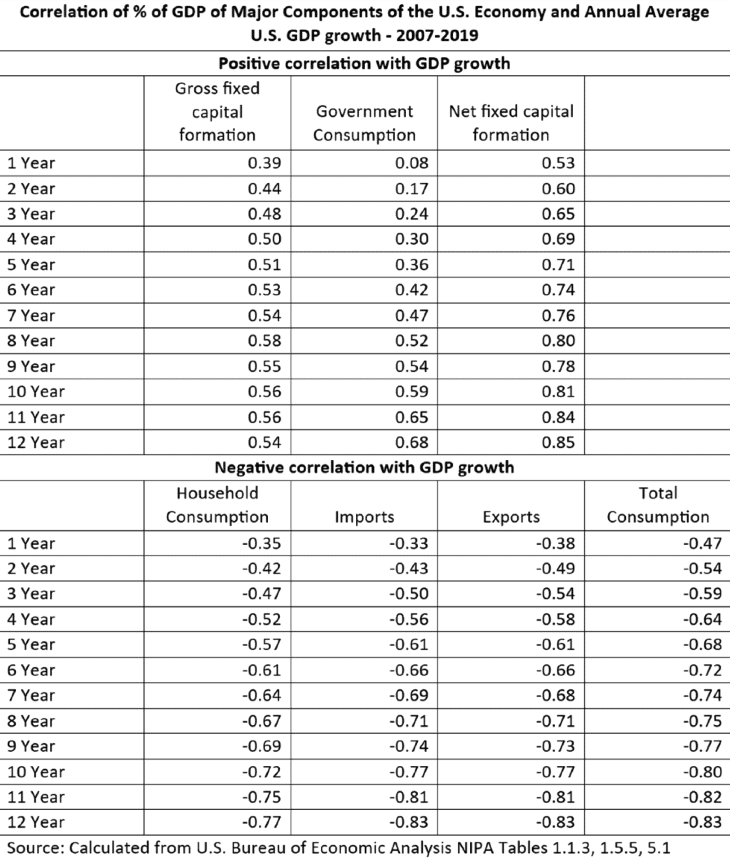

To then ascertain which policies would be necessary to speed up the U.S. economy it is necessary to analyse the underlying relation between changes in the structure of the U.S. economy and changes in U.S. GDP growth rates. Table 1 shows these for the entire last U.S. business cycle of 2007-2019.

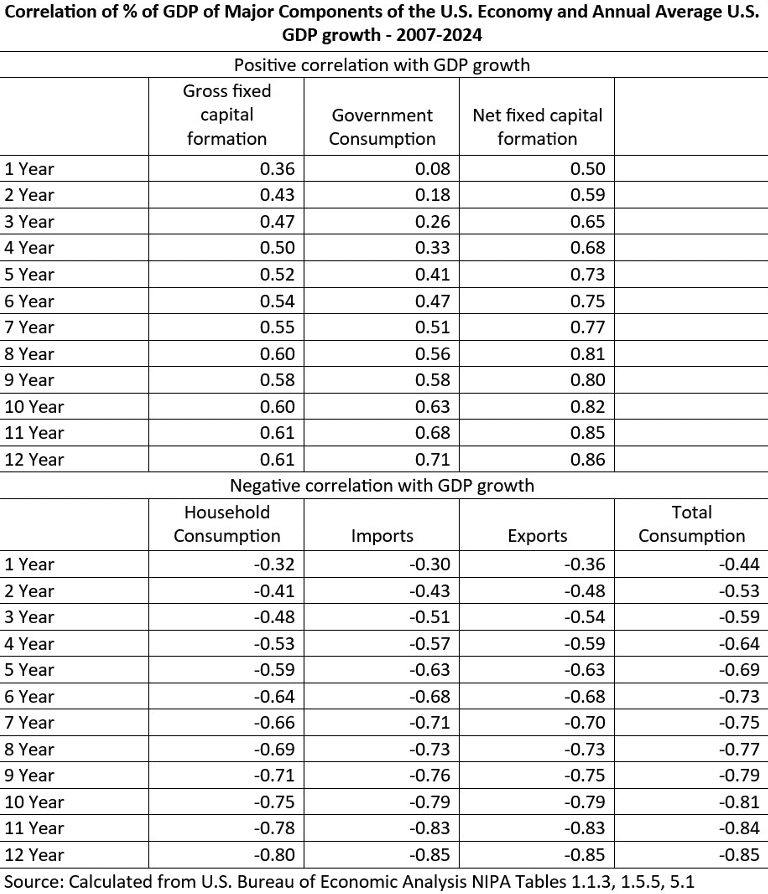

Statistically, to avoid distortions caused by short terms economic fluctuations, it is preferable to consider an entire business cycle, but to show that no “cherry picking” has been done Appendix 1 shows these correlations over the entire period from prior to the international financial crisis, 2007, up to 2024. This appendix shows that this makes no fundamental change to the relative significance of changes in the structure of the U.S. economy.

Table 1 shows an entirely clear pattern:

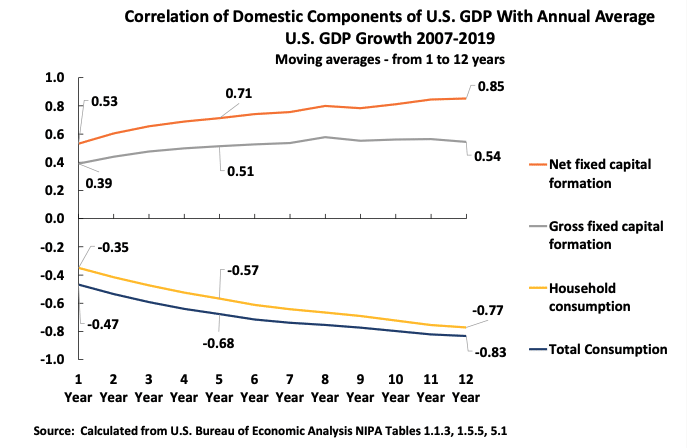

- If merely short-term periods are taken the correlation between changes in U.S. economic structure and its growth rate are moderate/low regardless of whether positive or negative correlations are considered—that is, whether an increase of the percentage of a particular component in U.S. GDP is associated with an acceleration or a deceleration of GDP growth. The highest correlation, taking a one-year period, is 0.53 for net fixed capital formation—a moderate correlation. All other one-year correlations, positive or negative, are between an extremely low 0.08 and a moderate/low 0.47.

- However as medium and longer-term periods are taken the correlations become progressively higher and higher. Taking positive relations, the correlation between the percentage of net fixed capital formation in GDP and GDP growth, the highest correlation for any factor in U.S. economic development, is 0.53 for one-year but rises to a high 0.71 for five years and an extremely high 0.85 over a 12-year period. Taking negative correlations, the 12-year correlations of household consumption in GDP, exports in GDP, imports in GDP and total consumption in GDP are all very high at between 0.77 and 0.85.

What such a data pattern demonstrates is that that in the short term no single factor in the U.S. economy is decisive. But in the medium/long term regarding positive correlations, the correlation of the percentage of net fixed capital formation in U.S. GDP and GDP growth is extremely high—that is an increase in the percentage of net fixed capital formation in U.S. GDP is associated with an increase in GDP growth. In direct contrast the correlation of the percentage of consumption in U.S. GDP and GDP growth is strongly negative—that is, the higher the percentage of consumption in U.S. GDP the slower will be GDP growth.

It is unnecessary, for present purposes, to establish the causal connection between the percentage of net fixed investment in GDP and GDP growth—that is whether the percentage of net fixed investment in GDP determines the rate of GDP growth, or the rate of GDP growth determines the percentage of net fixed investment in GDP, or some other factor(s) determine both. But the consequence of this extremely close correlation means that it is impossible to increase the rate of U.S. GDP growth without increasing the percentage of net fixed investment in GDP.

Therefore, for Trump to succeed in accelerating U.S. medium- and long-term growth, he has no option but to attempt to increase the percentage of net fixed capital formation in U.S. GDP.

The short, medium and long term

To show this situation still more clearly, and grasp its practical implications, Figure 8 shows visually the correlation between the major domestic components of U.S. GDP and annual GDP growth taking moving averages for different periods of years. Thus, as can be seen, if only a one-year period is taken there is only the medium correlation, 0.53, between the percentage of net fixed investment in GDP and annual GDP growth. There is also a low correlation, 0.39, between the percentage of gross fixed capital formation in GDP and GDP growth. There are negative low/medium correlations, -0.35 and -0.47, between the percentage of household consumption and the percentage of total consumption in GDP, and U.S. GDP growth.

This once more illustrates, as already noted above, that in the purely short term no single factor has a decisive influence on U.S. GDP growth. However, as the time frame increases from the short to the medium and long term the correlations become higher and higher:

- Taking a 5-year period the positive correlation between the percentage of net fixed investment in GDP and GDP growth has become a high 0.71, and the negative correlation between the percentage of total consumption in GDP and GDP growth is on the verge of becoming high at 0.68.

- By the time a long term 12-year period is taken the positive correlation between the percentage of net fixed investment in GDP and GDP growth is an extremely high 0.85, and the negative correlation between the percentage of total consumption in GDP and economic growth is also a very high 0.83.

The practical implication of these correlations is clear. In the short-term Trump can use other factors (e.g. budget deficits, short term boosts to consumption) to increase U.S. GDP growth, but in the medium and long term the only way that Trump, or any other U.S. President, can increase GDP growth is by increasing the percentage of net fixed investment in U.S. GDP. Similarly, while in the short-term stimuluses to consumption may increase U.S. GDP growth, over the medium and long-term increasing the percentage of consumption in GDP will slow U.S.GDP growth.

It should be noted that in this regard the U.S. is in the same position as China and all large economies—for the detailed data on this see 从210个经济体大数据中,我们发现了中国和世界经济增长的密码.1

U.S. economic correlations are in line with economic theory

These factual relations in the U.S. economy are entirely in line with economic theory. Consumption plus investment constitute 100% of domestic GDP. Investment is an input into production: therefore, increasing the percentage of the economy used for investment will increase the GDP growth rate. However, consumption, by definition, is not an input into production and therefore increasing the percentage of consumption in GDP, thereby reducing the percentage of inputs into production, will decrease the rate of GDP growth.

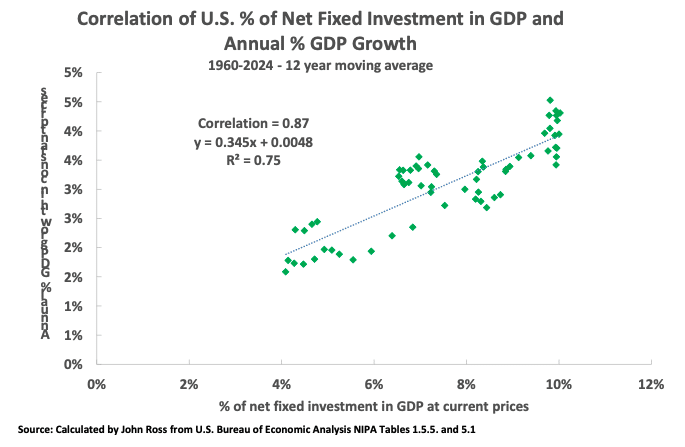

To take a longer period than the last business cycle, the extremely strong correlation between the long-term percentage of net fixed investment in U.S. GDP and U.S. GDP growth is confirmed in Figure 9 which takes the entire period of U.S. economic development since 1960—that is, over a 64 year period. As may be seen the long-term correlation between the percentage of net fixed investment in GDP and annual U.S. GDP growth is an extremely high 0.87.

Policy implications for Trump

In terms of practical policy for Trump, therefore already even in one year the percentage of net fixed investment in U.S. GDP has a significant if moderate correlation with annual U.S. GDP growth. But this correlation it is not so high that it dominates the situation. That is, in the short-term Trump could, at least theoretically, increase U.S. GDP growth by measures other than increasing the percentage of net fixed investment in GDP. But over the medium and long-term these extremely high correlations mean that this is impossible—the U.S. can only increase its rate of GDP growth by increasing the percentage of net fixed investment in GDP.

However, practically, a short-term period is quite insufficient to reverse the consequences of the situation of much lower growth in the U.S. than in China—this could only be reversed over a long time period. To accelerate the U.S. economy in a way capable of competing with China, therefore, Trump and succeeding U.S. presidents can only do this by increasing the level of net fixed investment in the U.S. economy. This objective situation strictly determines the policy choices which face Trump.

The negative relation between the percentage of consumption in GDP and the growth of consumption

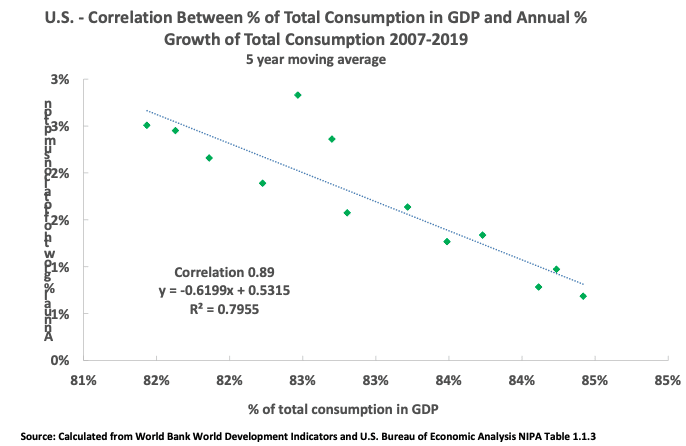

Given a confused discussion on consumption in some sections of the media, as an aside it should also be noted that the correlation between the percentage of consumption in U.S. GDP and the rate of growth of U.S consumption is strongly negative. That is, the higher the percentage of consumption in U.S. GDP the slower is the growth rate of U.S. consumption. In the case of U.S., taking a five-year moving average, the negative correlation between the percentage of consumption in GDP and the growth rate of consumption is an extremely high 0.89—see Figure 10. This is, in the U.S., the same negative correlation between the percentage of consumption in GDP and the rate of growth of consumption which exists in China and other major economies—for comprehensive data see 从210个经济体大数据中,我们发现了误解促消费对经济的危害.

This negative correlation between the percentage of consumption in U.S. GDP and GDP growth therefore confirms the extreme importance of distinguishing between the percentage of consumption in GDP and the rate of growth of consumption. Not only are they different things but they move in the opposite direction. That is in the U.S., as in China, the higher the percentage of consumption in GDP the slower will be the growth rate of consumption, and therefore the slower the growth rate of living standards.

International comparisons

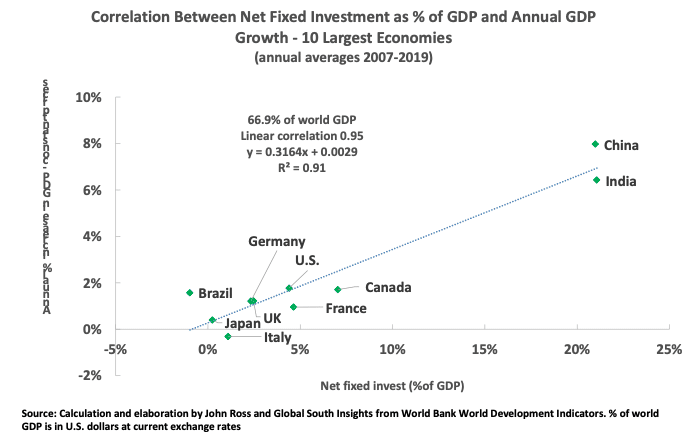

Finally, to complete the picture, it should be noted that this situation of the U.S. in regard to the relation between the percentage of net fixed investment in GDP and GDP growth, as already noted, is in line with other very large economies—all of which have very similar patterns of development. To see how strong this relation is, Figure 11 shows the development of the world’s 10 largest economies over the entire last international business cycle of 2007-2019. (Once again, the entire business cycle is taken to remove the effect of short-term business cycle fluctuations, although it should be noted that extending the figures to the latest available data makes no essential difference to the correlations despite the fluctuations created by Covid). For the world’s 10 largest economies, including China and the U.S., the positive correlation between the percentage of net fixed investment in GDP and annual GDP growth is 0.95—as close to a perfect correlation as will be found in any practical example.

Growth accounting

So far, to see accurately the determinants of U.S. economic development, the correlations of U.S. GDP growth with the structure of its economy as shown in the national accounts have been analysed. The reason for starting with this analysis is that national accounts are universally used in economics. However, it is also clarificatory to analyse the U.S. economy from the complementary viewpoint of growth accounting—that is measuring in terms of the inputs of capital, labour and total factor productivity (TFP). The fact that, as will be seen, the conclusions arrived at by the two methods are the same, confirms the decisive factors determining U.S. growth.

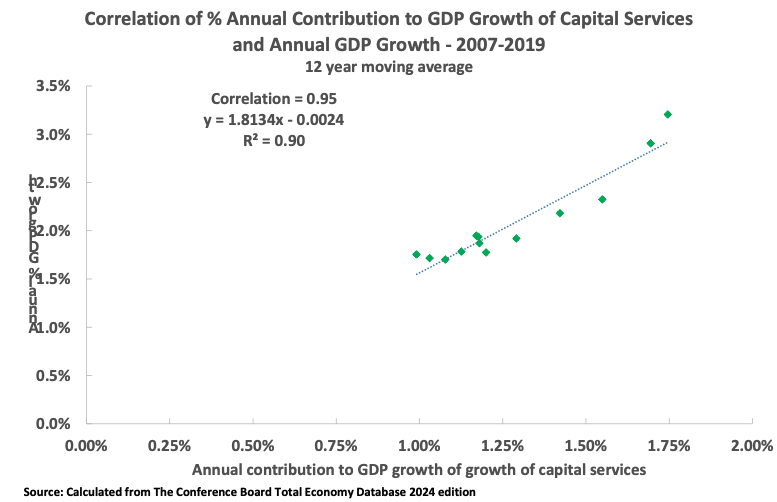

Taking long-term correlations, Figure 12 therefore shows the long-term correlation of the contributions of inputs of capital (capital services) to GDP growth and U.S. GDP growth during the whole of the last business cycle from 2007-2019. This shows an ultra-high correlation of 0.95 and an R squared of 0.90—once again as close to a perfect correlation as will be found in any real economic phenomenon.

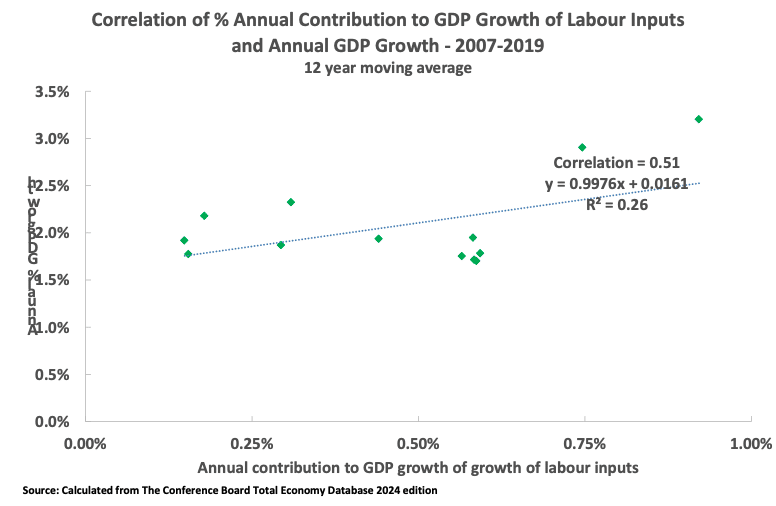

For comparison Figure 13 shows the correlation in the U.S. economy of the contribution to GDP growth of labour inputs. As may be seen the correlation is 0.51 and the R squared is 0.26—that is a moderate/low correlation.

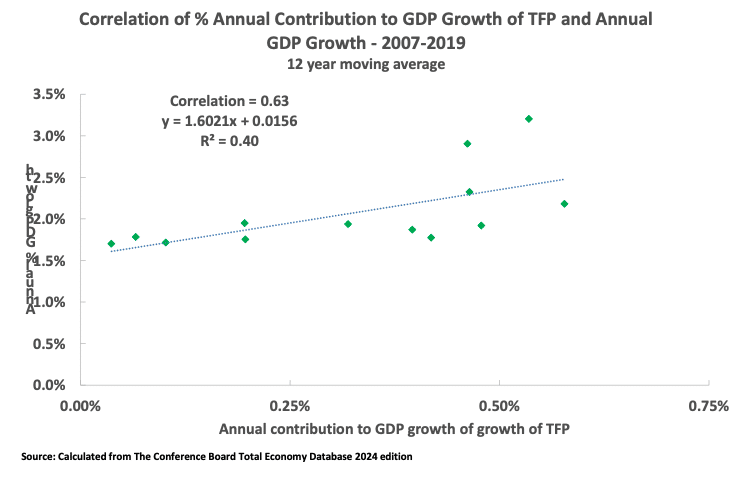

Figure 14 shows the correlation of the contribution of the growth of TFP and the annual growth of GDP in the U.S. economy. The correlation is 0.60 and the R squared 0.40—that is a moderate correlation.

In summary, there is an extremely high, almost perfect correlation, in the U.S. economy between capital inputs and GDP growth, a medium correlation between TFP growth and GDP growth, and a moderate/low correlation between labour inputs and GDP growth.

This finding of the extremely high correlation in the U.S. economy between capital inputs and GDP increase, using growth accounting methods, is entirely in line with the conclusion from national accounts data.

The contribution of factors of production to U.S. GDP growth

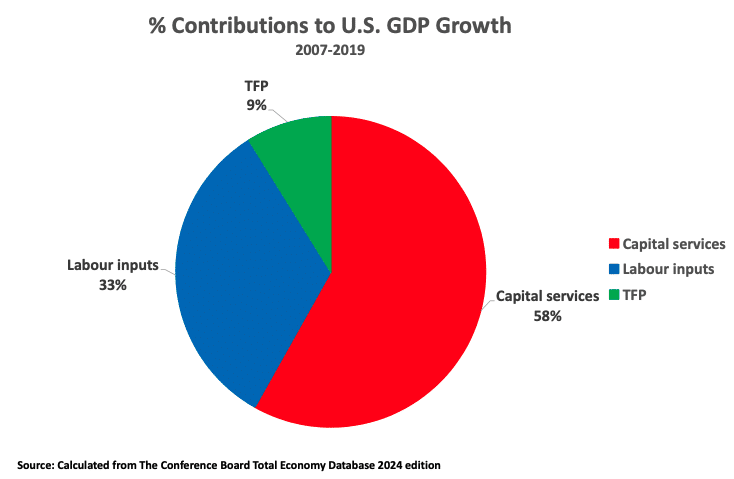

So far only the correlations between production inputs and GDP growth in the U.S. have been analysed. But this is insufficient by itself to analyse what are the key determinants of U.S. GDP growth: there may be a high correlation between an input into U.S. production and GDP growth, but if this factor of production only accounts for a small part of U.S. production it will not play a decisive role in U.S. GDP growth. Therefore, to accurately analyse the determining factors in U.S. growth, it is also necessary to know the relative weight of the different inputs. Figure 15 shows this. As may be seen by far the largest contributor to U.S. GDP growth is capital inputs (58%), second is labour inputs (33%) and finally growth in TFP is a small contribution (9%).

In short, therefore, summarising the significance of different factors of production in U.S. GDP growth:

- Capital investment dominates U.S. GDP growth, being both the highest contribution to growth and with the closest correlation to GDP growth.

- Labour inputs are the second largest source of growth in the U.S. economy, although having only slightly over half of the weight of capital inputs, but they have only a medium/low correlation with GDP growth.

- TFP has a moderate correlation with U.S. GDP growth but it only contributes a small part, 9%, of U.S. GDP growth.

In summary growth accounting confirms the national accounts data that capital investment is by far the decisive factor in U.S. economic growth.

Conclusion

In summary, to return to the starting point of whether Trump can close the gap in growth rates between China and the U.S.. If Trump cannot substantially slow China’s economy, the issue of which was discussed in 能否实现2035年远景目标?有一个关键事实中国无法回避, then it should be noted:

- In the short term, the U.S. economy under Trump is likely to experience some slowing in 2025.

- More fundamentally, the only way that Trump can increase the underlying growth rate of the U.S economy is by increasing the level of net fixed capital formation in U.S. GDP.

The reason that in this article such precise detail of the situation of the U.S. economy has been gone into is because this situation that Trump can only significantly increase the growth rate of the U.S. economy by increasing its level of net fixed investment in U.S. GDP is of fundamental importance—with huge consequences flowing from it. It means, if the U.S. cannot slow China’s economy, then the only way in which it can close the growth rate gap with China is by increasing the level of fixed investment in the U.S. The forms in which Trump attempts to increase the percentage of investment in GDP will therefore determine the dynamics of the U.S economy—with great consequences for U.S. domestic politics and U.S. geopolitics as it affects China.

Analysis of this will form the subject of the second article in this series.

Appendix 1—a technical statistical note

This appendix is not necessary to be read by non-economic specialists. It is included because the conclusion that it is impossible in practice to raise the U.S. GDP growth rate without increasing the level of net fixed capital formation in U.S. GDP is so fundamental in its consequences that it is included to show that there has been no “cherry picking” of the data and therefore it is impossible to escape the consequences of this correlation.

Statistically, as the U.S. economy, as with all capitalist ones, has business cycles, in addition to an underlying long term growth rate, it is preferable, to accurately see trends, to make calculations covering an entire business cycle—or from one point in one business cycle to the same point in another (for example from the top of one cycle to the top of another, or from bottom to bottom). Otherwise, cyclical effects obscure the fundamental trends or even produce entirely fallacious results. For example, if the starting point of measuring U.S. economic growth is taken as 1933, the bottom point of the Great Depression, to the peak of the last pre-World War II business cycle in 1937, then during that period the U.S. had an annual average growth rate of 9.4%. The 1930s might appear as a period of rapid economic growth! The reason for this is that the gigantic fall in U.S. GDP, of 26%, between 1929 and 1933 is ignored, that is two peaks in the business cycle are not being compared but a trough and a peak.

For this reason, in this article the entire U.S. business cycle from 2007-2019 is taken as the period focused on. However, to avoid any suggestion that 2019 is chosen as the end date to avoid bringing data up to date, Table 2 shows the entire period from 2007 to the latest available data, for 2024. As may be seen this makes no qualitative difference to the trends.

The one-year correlation between the percentage of net fixed capital formation in the U.S. economy and GDP growth is 0.50, which is a moderate correlation. However, if a five-year period is taken the correlation rises to a high 0.73 and if a 12-year correlation is taken it rises to an extremely high 0.85—by far the highest positive correlation of any major component of the U.S. economy and U.S. GDP growth.

This confirms the fact, the fundamental point, that in the short term no single factor has an extremely high correlation with U.S. GDP growth, but in the medium/long term the correlation between the percentage of net fixed capital formation and U.S. GDP growth is so high that it is impossible to speed up U.S. economic growth without increasing the percentage of net fixed capital formation in GDP and that any reduction in the percentage of nixed capital formation will reduce the GDP growth rate.

If there is a strong underlying correlation, however, then if very long periods of time are taken, as in the 1960-2024 period in Figure 9 above, then the correlations typically become less affected by whether similar periods in the business cycle are being compared.

The conclusion is therefore clear. In practice the U.S. cannot break out of its present low average annual growth, of slightly above two percent a year, without increasing the percentage of net fixed capital formation in GDP. Or, in comparative terms, if the U.S, cannot succeed in slowing China’s economy, then the U.S. can only decrease China’s lead in growth rate by increasing the percentage of net fixed capital formation in the U.S. economy.

Notes:

1. The only exceptions to this are the relatively small number of economies dominated by oil and gas exports, which is not relevant for either the U.S. or China, as neither are dominated by oil/gas exports.