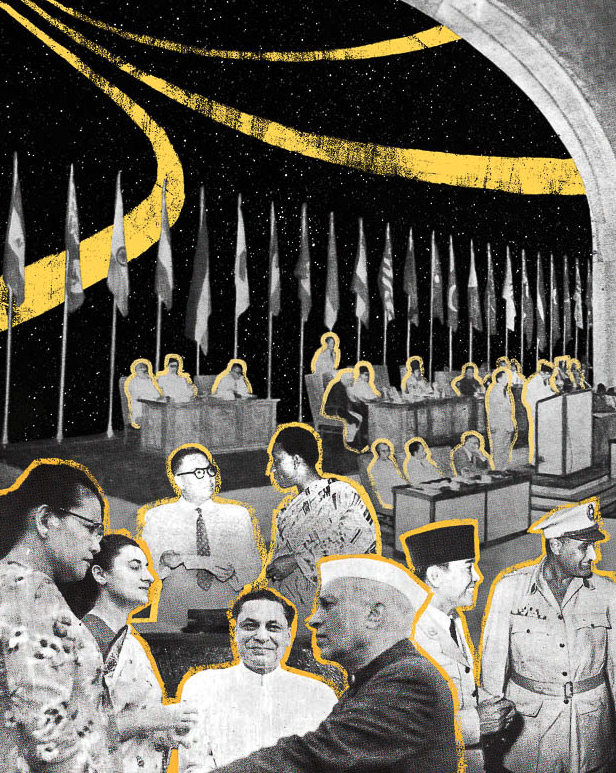

The art in this dossier honours the Bandung Conference, where diverse peoples, nations, and political projects, each following their own trajectory—or orbits—came together, gravitating around a shared struggle to build a world beyond colonialism. Anti-colonial leaders and nations were brought together by the Bandung Spirit, represented by a yellow thread weaving through the pages of the dossier. From that era’s aspirations for national liberation, new threads, new trajectories, and a new mood are emerging in the Global South today.

Seven decades ago, in 1955, the heads of government of twenty-nine African and Asian countries, as well as representatives from colonies that had not yet won their independence, met in Bandung (Indonesia) for the Asian-African Conference. It was one of the high points in the process of decolonisation. This was a historical gathering because it was the first time that representatives of hundreds of millions of people from the Third World came together to discuss the enormous social process known as decolonisation and assess its implications. Sukarno (1901—1970), who headed the government of Indonesia and hosted the conference, opened it with a speech that suggested the ambitions of the people who organised it. He said that he wanted the conference to ‘give guidance to humankind’ and that this guidance would ‘point out to mankind the way which it must take to attain safety and peace’. These leaders gathered not only to celebrate the independence of India (1947), the Chinese Revolution (1949), and the devolution of power in the Gold Coast (1951) that would eventually lead to a free Ghana (1957); they wanted to ‘give evidence that a New Asia and a New Africa have been born’.1

Sukarno’s associate Roeslan Abdulgani (1914—2005) was the secretary-general of the Bandung Conference. During and after the conference, he began to speak about a ‘Bandung Spirit’, which he described as ‘the spirit of love for peace, anti-violence, anti-discrimination, and development for all without trying to intervene for one another wrongly, but to pay a great respect to one another’.2 This ‘Bandung Spirit’ was not idealistic; it had a material basis rooted in the freedom struggles of peoples in the colonised world, which the United Nations General Assembly described five years later in the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples as ‘a process of liberation’ that is ‘irresistible and irreversible’.3

This spirit was born in the mass struggles against colonialism and was then brought together by anti-colonial activists as they met in places such as the Sixth International Democratic Congress for Peace in Bierville, France, (1926) and the First International Congress against Colonialism and Imperialism in Brussels, Belgium (1927). Abdulgani later reflected that those who met at these conferences had ‘the same impassioned spirit, and they all spoke with the same reverberating voice: that is the spirit and the voice of their peoples, who were colonised, oppressed, and humiliated’.4 The Bandung Spirit was the voice of the hundreds of millions who had lived under colonial rule and who spoke against the horrendousness of colonialism as well as their hope for a new world.

For a range of reasons, largely spurred on by the pressures from the neocolonial structure that continued despite the end of formal colonial rule, the Bandung Spirit dissipated. Only nostalgia for it remained. Generations born after colonial rule no longer held close to them the residue of the long and difficult anti-colonial struggles. The national liberation agenda corroded within those neocolonial structures; the peasants and workers of the post-colonial era saw their own ruling classes as the problem and did not see the inherited problems of that intractable structure as their enemy. Seventy years after the Bandung Conference, it is worthwhile to ask if the Bandung Spirit remains intact, even as an ethereal fog in the Global South. That is the objective of this dossier, more an extended essay that raises some provocations rather than the fruit of a long-term research programme.5 We hope that these provocations will generate discussion and debate.

Part I: What the Bandung Spirit Meant

Interlopers in an Oriental World

From 5 October to 14 December 1953, U.S. Vice President Richard Nixon went on an extensive tour of Asia, visiting fourteen countries in the region (from Japan to Iran) and two countries on its edge (Australia and New Zealand). Nixon came to Asia with a few important objectives: to reassure U.S. allies about the armistice signed on the Korean peninsula in July; to assess the U.S. position in Indochina, where it had already taken on the bulk of military financing from France and would later take over its military role after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu in May 1954; and to understand the new role of the Chinese Revolution in Asia. In his memoirs, written two decades later, Nixon reflected on this visit and said that ‘when wishful thinkers in Washington and other Western capitals were saying that Communist China would not be a threat in Asia because it was so backward and underdeveloped’, he saw ‘firsthand that its influence was already spreading throughout the area’. Unlike the Soviets, Nixon wrote, who ‘like us, were still interlopers in an Oriental world’, ‘the Chinese Communists had established student exchange programs, and large numbers of students were being sent to Red China for free college training’.6 The United States, Nixon reported to his government, had to respond vigorously to the new developments in Asia that had been spurred on by the Chinese Revolution.

In September 1954, eight countries formed the South-East Asian Treaty Organisation (SEATO) following the signing of a collective defence treaty called the Manila Pact. Only three of the countries were situated in Asia (Pakistan, the Philippines, and Thailand), while two were in Europe (France and the United Kingdom). The three other members of SEATO had already signed a military pact in 1951 called the Australia, New Zealand, and the United States Security (ANZUS) Treaty. This treaty and SEATO came alongside three other key treaties in the Pacific flank of Asia: the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty between Japan and the Allied Powers, the 1953 Mutual Defence Treaty between South Korea and the U.S., and the 1954 Mutual Defence Treaty between the Republic of China (then Formosa, now Taiwan) and the U.S.7 In 1951, John Foster Dulles, who became the secretary of state in 1953, argued that the United States needed to build an island chain of naval bases from Japan to the Malay Peninsula (which encompasses parts of Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore) to encircle the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). These five treaties laid the groundwork for such a chain from Japan to Thailand.8 In 1956, a U.S. State Department official received a British memorandum ‘regarding SEATO Military Planning proceeding on the assumption that nuclear as well as non-nuclear weapons will be used in defence of the area… Any planning which did not take into account nuclear weapons would obviously be unrealistic and not worthwhile’.9 In other words, the five treaties that encircled China encouraged the placement of nuclear weapons on the edge of Asia and authorised their use if necessary.

It is important to remember that none of this was merely theoretical. The United States had already used atomic bombs on Japan in 1945 and had bombed every available piece of infrastructure in the northern part of Korea by the end of 1951 (the bombing, however, continued until 1953).10 Major General Emmett O’Donnell, commander of the U.S. Air Force that bombed Korea, told the U.S. Senate in June 1951, ‘Everything is destroyed. There is nothing standing worthy of the name’. O’Donnell added that when the Chinese forces crossed the Yalu River on the border with North Korea in November 1950, the United States Air Force grounded its bombers because ‘There were no more targets in Korea’.11 In December 1953, U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower suggested to Winston Churchill that the U.S. would drop atom bombs on China if Beijing violated the Korean armistice. Shortly after, in March 1955, the United States government made it clear to the PRC that it was willing to use nuclear weapons if the People’s Liberation Army entered Formosa (now Taiwan).12

Peaceful Coexistence

In the wake of World War II, the United States was slowly establishing itself as the leading force of the old imperialist bloc, particularly because of its massive military and economic advantage over a battered Europe. At the same time, Britain was prosecuting a violent counterinsurgency in the Malaya Peninsula (the Malaya Emergency, 1948—1960) and France was fighting a wretched rearguard war in Indochina (the Dutch had already been defeated in Indonesia by 1949). Blood soaked into the soil of Asia and filled the nostrils of the anti-colonial leaders who came to Bandung. That is why the discussions at the conference were so focused on peace and racism: the anti-colonial leaders in attendance feared that the old colonial mentality of the international division of humanity would persist in the post-colonial era, as would the unbridled use of violence against those seen by the colonialists as being on the other side of that division. The Dasasila, or ten principles, of Bandung elaborated on the Panchsheel, or five principles, that China and India drafted in 1954 to help guide them through their differences. These principles of ‘peaceful coexistence’ strongly opposed building military alliances and bases around Asia and threatening countries with nuclear attacks.

In 1956, four years after Turkey joined NATO, the Turkish communist poet Nazim Hikmet wrote an elegy to a seven-year-old girl from Hiroshima titled ‘Hiroshima Child’, most known for the line ‘when children die, they do not grow’:

All that I need is that for peace

You fight today, you fight today

So that the children of this world

Can live and grow and laugh and play.

This was the essence of the Bandung Spirit. It was as simple as that. That essence permeates the ten principles, which were published in the conference’s final communiqué on 24 April 1955:

- Respect for fundamental human rights and for the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations.

- Respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all nations.

- Recognition of the equality of all races and of the equality of all nations large and small.

- Abstention from intervention or interference in the internal affairs of another country.

- Respect for the right of each nation to defend itself singly or collectively, in conformity with the Charter of the United Nations.

- (a) Abstention from the use of arrangements of collective defence to serve the particular interests of any of the big powers.

(b) Abstention by any country from exerting pressures on other countries. - Refraining from acts or threats of aggression or the use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any country.

- Settlement of all international disputes by peaceful means, such as negotiation, conciliation, arbitration, or judicial settlement as well as other peaceful means of the parties’ own choice, in conformity with the Charter of the United Nations.

- Promotion of mutual interests and cooperation.

- Respect for justice and international obligations.13

Effectively, these principles argued for an international order rooted in the UN Charter (1945) rather than one based on the creation of military blocs and the use of military force to shape the world and subvert sovereignty. In his reflections on the Bandung Conference, Abdulgani suggested that it was a forum to ‘determine the standards and procedures of present-day international relations’ and that it championed coexistence instead of co-destruction.14 By 1955, seventy-six countries had signed onto the UN Charter, which held treaty obligations towards its signatories; about eighty territories, including most of the African continent and a majority of the Pacific islands, remained under colonial control. The UN Charter was then, and remains now, the most important consensus document in the world; as countries gained their independence from the late 1950s to the 1970s, they joined the United Nations as full members.

The Bandung Spirit travelled rapidly, touching down in Cairo for the 1957—1958 Afro-Asian Peoples’ Solidarity Conference and then in Accra for the 1958 All-African Peoples’ Conference before continuing to Tunis for the 1960 All-African Peoples’ Conference, Belgrade for the 1961 Summit Conference of Heads of State or Government of the Non-Aligned Movement, and finally to Havana for the 1966 Tricontinental Conference. Each of these conferences established institutional organs: the Afro-Asian Peoples’ Solidarity Organisation, the Non-Aligned Movement, and the Organisation in Solidarity with the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. At their core was the fight against imperialism, with a focus on the nuclear threat and disarmament and the recognition that the waste of precious social wealth on weapons meant that the development agenda was being squandered. That calculation between guns and butter was at the heart of the deliberations. Any arms control mechanisms that developed during this period, such as the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty, were a product of the negotiations forced by these non-aligned Third World state projects.15

Developmental Cooperation

Beyond the call for sovereignty and peace, the Bandung era also carried within it the seed for a new international economic order. South-South cooperation was the clarion call at Bandung. The first section of its final communiqué was dedicated entirely to economic cooperation and outlined the desire for economic development and technical assistance. There was also a call to establish the Special United Nations Fund for Economic Development in order to finance investment in these countries. As imperialism had only seen fit to develop the colonies as sites to produce raw materials, much emphasis was placed on the need to stabilise commodity prices and develop domestic capabilities to process these commodities before export.

One of the lasting effects of the Bandung Conference was its influence in shaping multilateral institutions and processes that continue to this day, albeit in an often diminished or coopted form.16 These include the establishment of the Special United Nations Fund for Economic Development in 1958, which would later transform into the United Nations Development Programme in 1965. There was also the establishment of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in 1964 and its New International Economic Order, a set of proposals that were adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1974. On UNCTAD’s sixtieth anniversary in 2024, Deputy Secretary-General Pedro Manuel Moreno declared, ‘It is with the same spirit [as the Bandung Conference] that nine years later the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, UNCTAD, was born’.17

A World of Coups

A few weeks before the Bandung Conference, in April 1955, U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles held a meeting with the British ambassador to the U.S., Sir Roger Makins. Dulles told Makins that he had been ‘considerably depressed’ about the ‘general situation in Asia’. This ‘situation’ was embodied by a speech made by Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister following its independence, in the Indian Parliament on 31 March 1955 in anticipation of the Bandung meeting, in which he attacked SEATO as a hostile pact, NATO for giving Portugal support to retain Goa in India, the apartheid regime in South Africa, and the West for ‘meddling’ in West Asia. Nehru’s speech, Dulles said, ‘had taken the general line that Western civilisation had failed and that some new type of civilisation was necessary to replace it’. This depressed Dulles, who wanted to scuttle the Bandung Conference since it was, he said, ‘by its very nature and concept anti-Western’.18

Coups in Iran (1953) and Guatemala (1954) announced the West’s refusal to allow a new world order to be built. This was followed by a series of coups in Africa (against the people of the Congo in 1961 and of Ghana in 1966), Latin America (against the people of Brazil in 1964), and Asia (against the people of Indonesia in 1965). Each of these four coups produced epicentres of imperialist reaction, with the new military regimes in these countries playing a continental role in suffocating any progressive developments. The coup in Indonesia, which resulted in the murder of a million communists, was almost revenge for Bandung.19

Part II: Why Is There No Bandung Spirit Today?

Bathed in Nostalgia

In April 1965, Sukarno’s beleaguered government held a ten-year anniversary conference with delegates from thirty-seven countries. Yet, it was a pale shadow of the original conference: Indonesia had suspended its United Nations membership in January, and its military would leave the barracks in October to overthrow Sukarno. In 1965, an attempt to hold a second Afro-Asian Conference in Algiers, Algeria, had to be cancelled due to the June 1965 overthrow of Ben Bella; the Sino-Soviet dispute; and divides between the newly independent African states, with the Casablanca Group eager for a strongly aligned form of Pan-Africanism and the Brazzaville Group advocating for closer ties to the old colonial masters. Because many of the institutions that came out of the Bandung Conference remained intact and would have a marked influence on world affairs over the decades to come, the failure to hold a second conference was not as indicative as it appears. What destroyed the Bandung Spirit was the Third World debt crisis, which catapulted the countries of the developing world into a permanent situation of debt and austerity and torpedoed their development aspirations. That was when the Bandung Spirit evaporated.

The Third World debt crisis was itself an indication of the Bandung Spirit’s inability to overcome, in a short time, the material basis of the neocolonial division of labour. While the subjective conditions for cooperation and exchange existed, the objective conditions did not. All the infrastructure inherited by the newly independent states had been constructed by imperialism to facilitate extraction from the periphery to the core. In 1963, over 70% of exports from developing countries were destined for developed countries.20 Ancient trade ties within what we now call the Global South had been severed by colonialism, and rebuilding them was not an easy task. Moreover, these newly independent states accounted for a small part of global trade, despite being home to the majority of the world population. Their low level of technological development also prevented any effective sharing of technical expertise.

Each of the newly independent states in the Bandung process had a unique character of capital formation and internal class structure, and each remained compartmentalised in the international division of labour determined by imperialism.21 xvii Unable to overcome the pattern of colonial underdevelopment and the imperialist onslaught of coups and counterinsurgency, the Third World debt crisis ushered in a shift from a spirit of cooperation to the law of competition. This crisis was used to divide and discipline the periphery and reincorporate it into a global market on terms favourable to multinational capital.22

In 2005, almost all the countries of Africa and Asia—106 out of 177—attended the fiftieth anniversary Asian-African Summit in Bandung (Israel was not invited, nor were Australia or New Zealand, but most Pacific Island states and Palestine participated), and several Latin American countries were present as observers. Heads of government left the Sovay Homann hotel and walked down Asian-African Street (named in commemoration of the first conference) to the venue, just as their predecessors had done fifty years previously. The gathering was bathed in nostalgia, but also in a sense that the world was in transition despite this conference being held in the midst of the ugly War on Terror that had already destroyed Afghanistan and Iraq and would soon lay waste to a range of other countries (including Indonesia itself, where the October 2002 bombings in Bali had brought this War on Terror to Southeast Asia). The final communiqué, A New Asian-African Strategic Partnership, was riddled with neoliberal concepts of comparative advantage and development targets, a departure from the anti-imperialist logic of the original declaration. The Bandung Spirit on display had been well bottled; it was not in the air. The point, then, was not to merely revive the ghost of Bandung, but to find its spirit once more.

The New Mood in the Global South

It was not until the Third Great Depression set in (2007—2008) that there was a vital realisation that the West would neither permit nor enable the advancement of the Global South. In 2009, that realisation produced the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) process, which in 2025 was expanded to include five other countries (Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates) and thirteen partner states.23 While the early BRICS summits focused on South-South cooperation, or trade and investment across the Global South, the subsequent summits have reintroduced the idea of economic independence from the Global North and the idea of political multilateralism rather than U.S.-driven unipolarity. Sixteen years is not enough time for the BRICS project to be subject to a full assessment. Even during these years, it has suffered from political differences between its member countries (China and India, for instance) and from the changing nature of their leaders (such as Brazil moving from Dilma Rousseff’s centre-left government to Jair Bolsonaro’s neofascistic government and then returning to the centre left under Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva). Buoyancy for the BRICS process and other such South-South structures came because of the economic growth that began to define the large countries of Asia (China, Vietnam, India, Bangladesh, and Indonesia in particular). In January 2025, on the seventieth anniversary year of the Bandung Conference, Indonesia became a full member of BRICS.

The shift of the world economy’s centre of gravity to Asia birthed the start of a new confidence, or ‘new mood’, in the Global South since the countries of Africa, Asia, and Latin America no longer had to rely so fully on the institutions of the Global North for finance and technology. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), adopted in 2013 in response to the Third Great Depression, was an extremely important development in this regard, as it provided objective conditions for South-South cooperation that simply did not exist at the time of the Bandung Conference. Initiatives such as the construction of railways in East Africa and the opening up of a new port in Peru create pre-conditions for internal trade between the countries of the Global South. By 2023, 46.6% of China’s trade was with countries in the BRI network.24 While it is far too early to say that anything resembling ‘delinking’ has happened, it is clear that a major shift is taking place as China is now the major trading partner for over 120 countries.25 Meanwhile, the BRI itself has had its share of ups and downs and requires its member countries to bring their own national development projects to the table.

In many of Tricontinental’s publications, we have used the phrase ‘new mood’ to define the present. The principal objectives of the ‘new mood in the Global South’ are rooted in two concepts, regionalism and multilateralism, both motivated by a desire to democratise the world order in economic and political terms. From the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation to the Southern Common Market (Mercosur), this regionalism is already being developed and has been bolstered by an increase in local currency-denominated trade, making it materially possible to achieve ‘economic self-determination’ and ‘regional complementarity’, in the words of Indira López Argüelles of the Cuban Ministry of Foreign Affairs.26 Linked to this regionalism is the expansion of the idea of multilateralism, the belief that global institutes (such as the United Nations and the World Trade Organisation) must not be instruments of the Global North but must allow their agenda to be shaped by all of their member states.

There Is No Bandung Spirit Today

In the 1950s and 1960s, national liberation movements had a mass base (often the majority of their populations). Despite being led—in most cases—by the petty bourgeoisie and sections of the landed elite, these movements’ commitment to national liberation forced them toward a socialist path, to take over governments within the structures of neocolonialism, and to respond to their organised mass base. These ‘socialisms’ came with different orientations, whether the ‘socialist path to society’ of India’s second Five-Year-Plan (1956—1961), the African socialism of the Arusha Declaration (written by Julius Nyerere of Tanzania in 1967), or indeed the mass politics of variants of populism in Latin America such as Argentinian Peronism (¡Ni yanquis, ni marxistas!, ¡peronistas!, or ‘Not Yankees, not Marxists, peronistas!’). Despite the class orientations of the leadership of these tendencies and the narrowness of their own perspectives, the activated masses would not permit them to abandon the widest programme of national liberation. That is why we can talk of a Bandung from below.

Today, the state of people’s movements is much weaker. Only in a few countries in the Global South do they command society. The progressive governments of our times are coalitions of a range of classes—including a petty bourgeoisie and liberal bourgeoisie that can no longer tolerate the atrocities of neoliberalism but will not easily break with its orthodoxies. While the second pink tide in Latin America, for example, and the emergence of progressive governments in countries such as Senegal and Sri Lanka are an effect of the collapse of neoliberalism and a response to the horror of the right, they are not elevated upon the backs of organised mass movements, nor are they united around a programme that breaks with neoliberalism.27 Across the Sahel region of Africa—in Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso—anti-imperialist military coups are backed by a new wave of social movements that are still in the process of formulating a broader project for sovereignty and development. These developments are capable of a new mood—a ‘BRICS Spirit’, for example—but not yet of the equivalent of the Bandung Spirit. It would be premature, even idealistic, to announce such a phenomenon, a Bandung Spirit from below for our time, a mass phenomenon capable of driving the actual movement of history.

The fundamental context shaping this new mood, and the looming threat that necessitates the revival of the Bandung Spirit, is hyper-imperialism.28 In our research at Tricontinental, we have proposed that there is only one true political-economic-military bloc in the world: the U.S.-led alliance of NATO and Israel. Despite waning economic and technological power, this bloc retains unparalleled military might and significant control over the global information system. The use of hybrid war tactics, and the threat or use of violence against even modest sovereignty-seeking nations, requires a collective response from the Global South, which may take the form of a rekindling of the Bandung Spirit.

However, there are a set of factors that limit the emergence of a new Bandung era in the Global South:

- There remains both a fear of and desire for Western leadership despite its many failures, its decadence, and its dangerousness. It is logical that the states of the Global South fear the possibility of war by all means (from unilateral coercive measures to aerial bombardment) because this is not a theoretical assumption, but an actual fact.29 Yet, at the same time, there is a captivating sense that Western leadership is necessary given the remains of the Western-dominated international order.

- There is a lack of clarity in the Global South about the advances made in Asia, especially by China. Other countries do not see these gains—particularly when it comes to the qualitatively new productive forces—as easily replicable, which leads to a mutual underestimation of the potential strength of a collective Global South. There is, furthermore, and against the available evidence, a growing belief pushed by the Global North that the advances of the locomotives of the Global South will be dangerous for the poorer countries. It is being suggested that the advances of Asian countries, in particular, are more of a threat than the record of danger from the Global North over hundreds of years.

- There is a surrender to the reality of the West’s control over the digital, media, and financial landscapes, which is made to seem unsurpassable.

- A significant portion of the ruling economic elite in the Global South remains deeply intertwined with global financial capital. This is particularly manifest in their dependency on the U.S. dollar as a safe haven for investment and their participation in extracting wealth from their own countries to invest in the Global North’s real estate and financial markets. These class interests are readily supported by intellectuals and policymakers who cannot see beyond the theories of neoclassical economics and the Washington Consensus.30 That is why we at Tricontinental have argued for a new development theory for the Global South.31

- There are old habits in many of our social movements that the left must permanently oppose the realities of class politics and that we cannot win power in these conditions. Any compromise with reality to take power and build our agenda further is seen as a dissolution of our final aims. The failure to win is a captivating sensibility that was unknown in the national liberation era, when winning state power was the immediate and intractable goal. There is even an orientation that suggests that left movements should fight the right, build a dynamic against neoliberalism, and then, rather than demand and seize state power, deliver power to the centre left. The worst orientation is to not contest state power at all.

Until the peoples of the Global South are able to overcome some of these (and more) challenges, it is unlikely that the Bandung Spirit will be part of the actual movement of history. We are emerging slowly out of a defunct epoch of history, the epoch of imperialism. But we have not yet emerged into a new period that is beyond imperialism—the hardest of all structures from which to break.

Notes

1. Sukarno, ‘Opening address given by Sukarno (Bandung, 18 April 1955)’, Asia-Africa Speak from Bandung (Djakarta: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Indonesia, 1955), 19—29.

2. Roeslan Abdulgani, Bandung Spirit: Moving on the Tide of History (Djakarta: Prapantja, 1964) and The Bandung Connection: The Asia-Africa Conference in Bandung in 1955 (Singapore: Gunung Aguna, 1981), 89.

3. The poetic resolution was formally placed before the UN General Assembly by the Soviet diplomat Vasily Kuznetsov. See United Nations General Assembly, Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples (A/RES/1514), December 14, 1960. The president of the General Assembly at that time was the Irish diplomat Frederick Boland. Boland’s daughter Eavan became a famous poet and in 1998 published ‘Witness’, which contains these lines:

What is a colony

if not the brutal truth

that when we speak

the graves open.

And the dead walk?

4. Abdulgani, The Bandung Connection, 11.

5. The overall narrative in this dossier draws heavily from Vijay Prashad, The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World (New York: The New Press, 2007) and The Poorer Nations: A Possible History of the Global South (New Delhi: LeftWord, 2013). It will form part of the basis for The Brighter Nations (2026).

6. Richard Nixon, RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1978), 136. Also see Richard Nixon, ‘Asia After Viet Nam’, Foreign Affairs, 1 October 1967, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/1967-10-01/asia-after-viet-nam.

7. For more on the San Francisco Treaty, see Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, The New Cold War Is Sending Tremors through Northeast Asia, dossier no. 76, 21 May 2024, https://thetricontinental.org/dossier-76-new-cold-war-northeast-asia/.

8. For a full sense of the argument, see John Foster Dulles, Policy for the Far East (Washington: U.S. Government Publishing Office, 1958).

9. ‘Memorandum of a Conversation Between the Counsellor of the Department of State (MacArthur) and the British Ambassador (Makins), Department of State, Washington, February 29, 1956’, U.S. Department of State, Conference Files: Lot 62 D 181, CF 656, Secret; John P. Glennon, Edward C. Keefer, and David W. Mabon, eds., Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955—1957, East Asian Security; Cambodia; Laos, Volume XXI, (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1990), 180—181.

10. Su-kyoung Hwang, Korea’s Grievous War (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

11. I. F. Stone, The Hidden History of the Korean War, 1950—1951 (New York: Little Brown, 1969), 312.

12. At a press conference on 15 March 1955, John Foster Dulles explained the doctrine of ‘less-than-massive retaliation’. If China crossed into Formosa, Dulles said, the U.S. would use tactical nuclear weapons against the Chinese forces. See Elie Abel, ‘Dulles Says U.S. Pins Retaliation on Small A-Bomb’, New York Times, 16 March 1955, https://www.nytimes.com/1955/03/16/archives/dulles-says-us-pins-retaliation-on-small-abomb-lessthanmassive.html.

When Eisenhower was asked to confirm Dulles’ statement the next day, he said that tactical nuclear weapons should not be used ‘just exactly as you would use a bullet or anything else. I believe that the great question about these things comes when you begin to get into those areas where you cannot make sure that you are operating merely against military targets. But with that one qualification, I would say, yes, of course they would be used’. See William Klingaman, David S. Patterson, and Ilana Stern, eds., Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955—1957, National Security Policy, Volume XIX ( Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1990), 61. For Churchill’s diary notes, see John Colville, The Fringes of Power: Downing Street Diaries, 1939—1955(London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1985), 687. On the broader question of nuclear retaliation, see Matthew Jones, ‘Targeting China: U.S. Nuclear Planning the “Massive Retaliation” in East Asia, 1953—1955’, Journal of Cold War Studies 10, no. 4 (Fall 2008): 37—65.

13. Asia-Africa Speak from Bandung, 161—169.

14. Abdulgani, Bandung Spirit, 72.

15. For example, L. C. N. Obi of Nigeria was a key, but now forgotten, figure in the debate around the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty while Ismael Moreno Pino of Mexico was the central negotiator for the 1967 Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean, known as the Tlatelolco Treaty, the first to establish a nuclear weapons free zone.

16. Gilbert Rist, The History of Development: From Western Origins to Global Faith (London: Zed Books, 2008).

17. Pedro Manuel Moreno, 60 years of UNCTAD: Charting a New Development Course in a Changing World, UN Trade and Development, 14 May 2024, https://unctad.org/osgstatement/60-years-unctad-charting-new-development-course-changing-world-session-1.

18. John P., Harriet D. Schwar, and Louis J. Smith, eds., ‘Memorandum of a Conversation, Department of State, Washington, April 7, 1955’, in Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955—1957, China, Volume II (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1986), 454.

19. Alan Burns, the governor of the Gold Coast and Nigeria from 1941 to 1947, was appointed to be the United Kingdom’s permanent representative at the UN Trusteeship Council from 1947 to 1956. Soon after leaving the UN, Burns published a book that went after Bandung and argued that it represented ‘the resentment of the darker peoples against the past domination of the world by European nations’. See Alan Burns, In Defence of Colonies (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1957), 5. For more on the coup in Indonesia, see Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, The Legacy of Lekra: Organising Revolutionary Culture in Indonesia, dossier no. 35, December 2020, https://thetricontinental.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/20210127_Dossier-35_EN_Web.pdf.

20. Bela Balassa, Trends in Developing Country Exports, 1963—88, Policy, Research, and External Affairs working papers no. WPS 634, World Bank World Development Report, 31 March 1991, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/561401468766799448/Trends-in-developing-country-exports-1963-88.

21. Aijaz Ahmad, In Theory: Classes, Nations, Literatures (London: Verso, 1992), 16.

22. S. B. D. de Silva, The Political Economy of Underdevelopment (London: Routledge, 1982), 506.

23. For more on the Third Great Depression, see Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, The World in Economic Depression: A Marxist Analysis of Crisis, notebook no. 4, 10 October 2023, https://thetricontinental.org/dossier-notebook-4-economic-crisis/.

24. The State Council Information Office, ‘China’s Trade with BRI Countries Booms in 2023 ’, press release, 12 January 2024, http://english.scio.gov.cn/m/pressroom/2024-01/12/content_116937407.htm#:~:text=China’s%20trade%20with%20countries%20participating,2022%2C%20customs%20data%20showed%20Friday.

25. Alessandro Nicita and Carlos Razo, ‘China: The Rise of a Trade Titan’, UN Conference on Trade and Development, 27 April 2021, https://unctad.org/news/china-rise-trade-titan. For more on delinking, see Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, Globalisation and Its Alternative: An Interview with Samir Amin, notebook no. 1, 29 October 2018, https://thetricontinental.org/globalisation-and-its-alternative/.

26. For more on regionalism, see Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, Sovereignty, Dignity, and Regionalism in the New International Order, dossier no. 62, 14 March 2023, https://thetricontinental.org/dossier-regionalism-new-international-order/.

27. For more on the second pink tide in Latin America, see Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, To Confront Rising Neofascism, the Latin American Left Must Rediscover Itself, dossier no. 79, 13 August 2024, https://thetricontinental.org/dossier-neofascism-latin-america/.

28. Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, Hyper-Imperialism: A Dangerous Decadent New Stage, Contemporary Dilemmas no. 4, 23 January 2024, https://thetricontinental.org/studies-on-contemporary-dilemmas-4-hyper-imperialism/; Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, The Churning of the Global Order, dossier no. 72, 23 January 2024, https://thetricontinental.org/dossier-72-the-churning-of-the-global-order/.

29. For more on unilateral coercive measures, see Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, Imperialist War and Feminist Resistance in the Global South, dossier no. 86, 5 March 2025 https://thetricontinental.org/dossier-imperialism-feminist-resistance.

30. For more on the role of intellectuals on both sides of the class struggle, see Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, The New Intellectual, dossier no. 12, 11 February 2019, https://thetricontinental.org/the-new-intellectual/.

31. Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, Towards a New Development Theory for the Global South, dossier no. 84, 14 January 2025, https://thetricontinental.org/towards-a-new-development-theory-for-the-global-south/.