Dear Friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

Eighty years ago, on 11 April 1945, units of General George S. Patton’s 4th Armoured Division of the U.S. armed forces drove toward the city of Weimar, Germany, where the Buchenwald concentration camp was located. Patton’s troops eventually took control of the camp, but soldiers’ statements, which were collected later by historians, suggest that the U.S. tanks were not what liberated Buchenwald: the camp had already been seized by the organisation and courage of the prisoners who took advantage of the flight of German soldiers in the face of the Allied advance.

Political prisoners in the Buchenwald concentration camp had formed themselves into combat groups (Kampfgruppen), which used their hidden cache of arms to foment an uprising within the camp, disarm the Nazi guards, and seize the tower at the camp’s entrance. The prisoners flew a white flag from the tower and formed a ring around the camp to inform the U.S. troops that they had already liberated the Buchenwald concentration camp. ‘Das Lager hatte sich selbst befreit’, they said; ‘the camp liberated itself’.

It was not only at Buchenwald that the prisoners rebelled. In August 1943, Treblinka prisoners rose up in an armed rebellion and, despite being gunned down, forced the Nazis to shut down this repulsive extermination camp (the Nazis murdered almost a million Jews in this camp alone).

The Soviet Union’s Red Army and U.S. forces also liberated several camps, most of them terrible death camps of the Holocaust. U.S. troops liberated Dachau in April 1945, but it was the Red Army that opened the doors to most of the worst camps, such as Majdanek (July 1944), Auschwitz (January 1945) in Poland and Sachsenhausen (April 1945) and Ravensbrück (April 1945) in Germany.

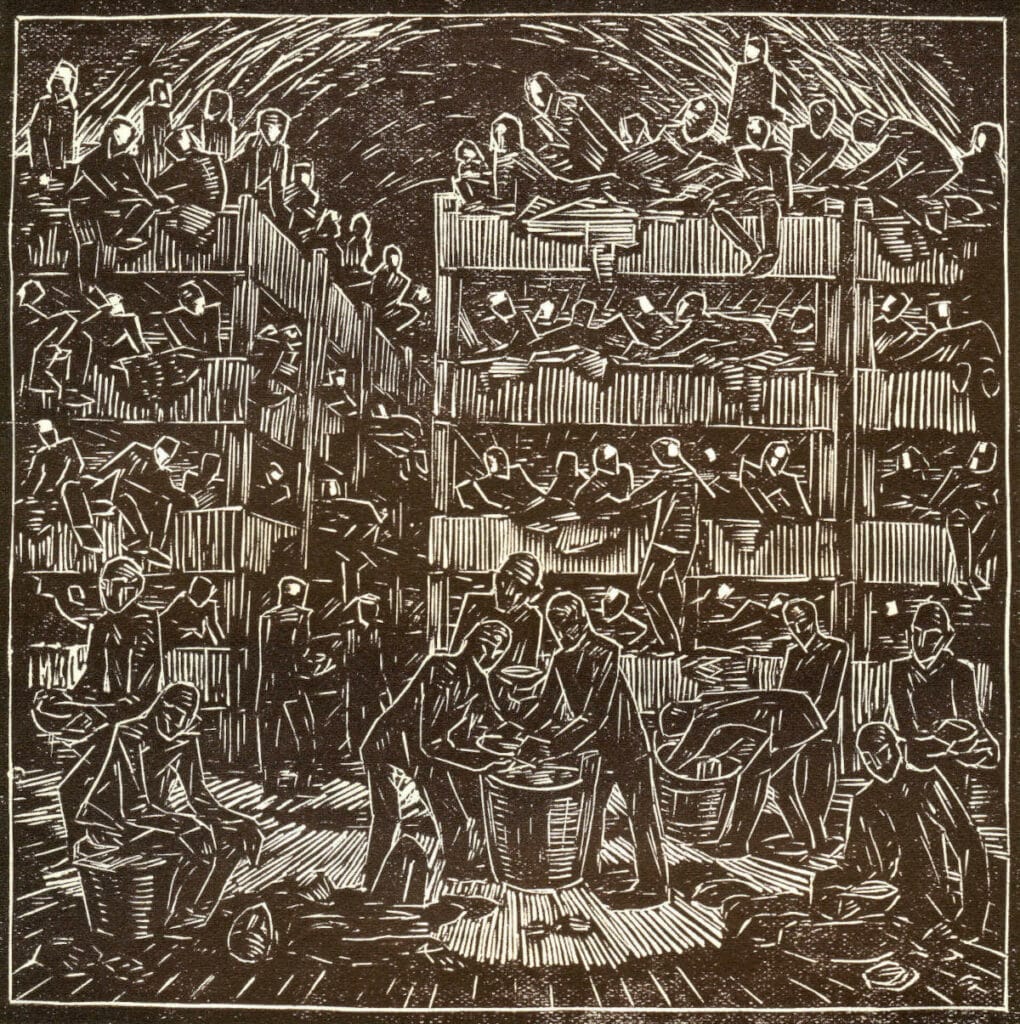

Dominik Černý (Czechoslovakia), K.L. Dora: Bydlení ve štole (K. L. Dora: Living in the Tunnel), 1953.

In July 1937, the Nazi regime brought prisoners from Sachsenhausen to an area near Weimar (home to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller as well as the site where the 1919 German Constitution was signed). The prisoners cleared nearly 400 acres of forest to build a concentration camp to hold 8,000 people, who Nazi camp commander Hermann Pister (1942—1945) used for medical experimentation and forced labour. By the camp’s closure eight years later, it held almost 280,000 prisoners (mostly Communists, Social Democrats, Roma and Sinti, Jews, and Christian dissidents). In late 1943, the Nazis shot to death nearly 8,500 Soviet prisoners of war in the camp and killed many Communists and Social Democrats. The Nazis killed an estimated total of 56,000 prisoners in this camp, including Communist Party of Germany (KPD) leader Ernst Thälmann, who was shot to death on 18 August 1944 after eleven years in solitary confinement. But Buchenwald was not an extermination camp like Majdanek and Auschwitz. It was not directly part of Adolf Hitler’s hideous ‘final solution to the Jewish question’ (Endlösung der Judenfrage).

Within Buchenwald, the Communists and Social Democrats set up the International Camp Committee to organise their lives in the camp and to conduct acts of sabotage and rebellion (including, remarkably, against the nearby armament factories). Eventually, the organisation matured into the Popular Front Committee, set up in 1944, with four leaders: Hermann Brill (German People’s Front), Werner Hilpert (Christian Democrats), Ernst Thape (Social Democrats), and Walter Wolf (Communist Party of Germany). What was remarkable about this initiative was that despite being prisoners, the committee had already begun to discuss the possible future of a new Germany that had been de-Nazified from top to bottom and would be based on a cooperative economy. While in Buchenwald, Wolf wrote A Critique of Unreason: On the Analysis of National Socialist Pseudo-Philosophy.

Nachum Bandel (Ukraine), Block 51. Buchenwald. Small Camp, 1947.

A week after the prisoners liberated Buchenwald, they placed a wooden sculpture near the camp as a symbol of their anti-fascist resistance. They wanted to remember the camp not for the killings, but for their resilience during their incarceration and in their self-liberation. In 1945, the prisoners had already shaped the Buchenwald Oath, which became their credo: ‘We will only give up the fight when the last guilty has been judged by the tribunal of all nations. The absolute destruction of Nazism, down to its roots, is our device. The building of a new world of peace and freedom is our ideal’.

The camp, then in the German Democratic Republic (DDR or East Germany), was converted into a prison for Nazis who awaited their trials. Some Nazis were shot for their crimes, including Weimar’s mayor, Karl Otto Koch, who had organised the arrest of Jews in the city in 1941. Meanwhile, across the Iron Curtain, the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) rapidly incorporated former Nazis into the state bureaucracy, with two thirds of the senior staff of the Bundeskriminalamt (the federal criminal police) made up of former Nazis. As the process of trials and punishment for the Nazis came to an end, the remnants of Buchenwald became part of the project of public memorialisation in the DDR.

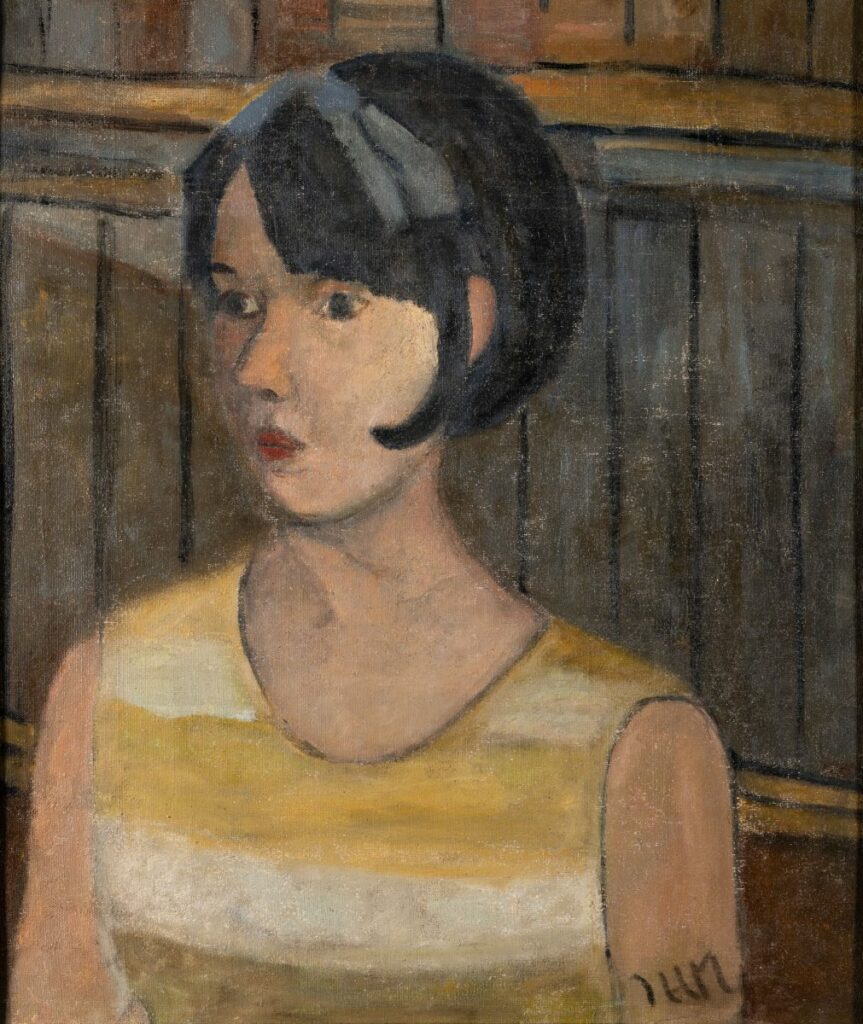

Ilse Häfner-Mode (Germany), Portrait of a Woman in Front of a Wooden Door, n.d.

In 1958, Otto Grotewohl, a social democrat who was the first prime minister of the DDR, opened the camp to hundreds of thousands of workers and school children to visit the buildings, listen to the stories of both the atrocities and the resistance, and commit themselves to anti-fascism. That same year, former prisoner Bruno Apitz published Nackt unter Wölfen (Naked Among Wolves), which told the story of how the resistance movement in the camp hid a little boy at great risk to the movement itself, and then how the movement captured the camp in 1945. The novel was made into a film in the DDR by Frank Beyer in 1963. The story was based on the actual account of Stefan Jerzy Zweig, a boy who was hidden by the prisoners in order to spare him from being sent to Auschwitz. Zweig survived the ordeal and died at the age of 81 in Vienna in 2024.

The DDR shaped its national culture around the theme of anti-fascism. In 1949, the Ministry of People’s Education urged schools to build a calendar of events that highlighted the anti-fascist struggle rather than religious holidays, such as World Peace Day instead of Fasching (Mardi Gras). The old Jugendweihe (youth initiation ceremony) was reshaped from being merely a rite of passage to an affirmation for young people to commit themselves to anti-fascism. Schools would take their students on field trips to visit Buchenwald, Ravensbrück, and Sachsenhausen to learn about the hideousness of fascism and to cultivate humanist and socialist values. This was a powerful exercise in social transformation for a culture that had been swept into Nazism.

Herbert Sandberg (Germany), We Didn’t Know, 1964.

When West Germany annexed the east in 1990, a process began to undermine the advances of anti-fascism developed in the DDR. Buchenwald was ground zero for this exercise. First, leadership at Buchenwald became a controversy. Dr. Irmgard Seidel, who took over from former KPD prisoner Klaus Trostorff in 1988, found out that she had been sacked through a newspaper article (by investigating SS records, Dr. Seidel had discovered that there were 28,000 women prisoners at Buchenwald who worked as slave labourers, largely in the armaments factories). She was replaced by Ulrich Schneider, who was then removed when it was revealed that he had been a member of the communist party in West Germany. Schneider was followed by Thomas Hofmann, who was sufficiently anti-communist to please the new political leaders. Second, the anti-fascist orientation of public memory had to be altered to encourage anti-communism, such as by downplaying the memorial to Thälmann. A new emphasis was placed on the Soviets’ use of Buchenwald to imprison the Nazis.

Historians from Germany’s west began to write accounts saying that it was Patton’s soldiers, not the prisoners, who liberated the camp (this was the interpretation, for instance, of Manfred Overesch’s influential Buchenwald und die DDR. Oder die Suche nach Selbstlegitimation [Buchenwald and the DDR. Or, the Search for Self-Legitimisation], 1995). In June 1991, German Chancellor Helmut Kohl presided over a ceremony to install six large crosses for the victims of ‘the communist terror dictatorship’ and spoke of the Nazi crimes as if they were identical to the actions of the Soviet Union. Between 1991 and 1992, the German historian Eberhard Jäckel led a commission to rewrite the history of Buchenwald, including accusing the communist prisoners of collaborating with the Nazis and commemorating the ‘victims’ of the anti-fascist prison. This was an official reordering of historical facts to elevate fascists and undermine the antifascists. Such historical revisionism has reached new heights in recent years. Diplomatic representatives from Russia and Belarus—two former Soviet Republics—have been uninvited from the annual commemoration events. In speeches held at the memorial, speakers have equated Nazi concentration camps with Soviet work camps. And while Israeli flags have been openly displayed in Buchenwald, visitors wearing the keffiyeh have been banned from the premises and any mention of the genocide in Palestine has been reprimanded.

Hilde Kolbe takes her class of Vietnamese students from the Dorothea Christiane Erxleben Medical School in Quedlinburg, DDR, to Buchenwald, 15 April 1976.

In the 1950s, communist artists joined together to build a set of memorials at Buchenwald commemorating the fight against fascism. Sculptors René Graetz, Waldemar Grzimek, and Hans Kies created relief steles with a poem by the DDR’s first culture minister Johannes R. Becher etched on the back:

Thälmann saw what happened one day:

They dug up the weapons that had been hidden away

From the grave the doomed men rose

See their arms stretched out wide

See a memorial in many a guise

Evoking our struggles present and past

The dead admonish: Remember Buchenwald!

In this newsletter, the paintings are by former Buchenwald prisoners and the photograph depicts ‘Revolt of the Prisoners’, a large bronze sculpture of the prisoners liberating themselves made by Fritz Cremer, who joined the KPD in 1929.

Warmly,

Vijay

PS: in June, the Zetkin Forum for Social Research will convene a conference against fascism in Berlin, to which you are all invited.